Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus

| Resident Survival Guide |

|

Unstable angina / NSTEMI Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Unstable Angina/Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction from other Disorders |

|

Special Groups |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Laboratory Findings |

|

Treatment |

|

Antitplatelet Therapy |

|

Additional Management Considerations for Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy |

|

Risk Stratification Before Discharge for Patients With an Ischemia-Guided Strategy of NSTE-ACS |

|

Mechanical Reperfusion |

|

Discharge Care |

|

Case Studies |

|

Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus On the Web |

|

FDA on Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus |

|

CDC onUnstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus |

|

Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus in the news |

|

Blogs on Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus |

|

to Hospitals Treating Unstable angina / non ST elevation myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Smita Kohli, M.D.

Overview

75% of all deaths among diabetic patients are due to coronary artery disease. Diabetic patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI tend to have a more severe disease with worse outcomes. Long term morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients with no previous cardiovascular disease are the same as that of nondiabetic patients with established cardiovascular disease after hospitalization for unstable coronary artery disease.[1]

Diabetic Patients with Unstable Angina/NSTEMI

- Patients with diabetes tend to have more extensive noncoronary vascular comorbidities, hypertension, LV hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure.

- Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounts for 75% of all deaths in patients with diabetes mellitus.

- Patients with UA/NSTEMI and diabetes tend to have more severe CAD and have been shown to have worse adverse outcomes as compared to non-diabetic patients.

- In addition, diabetic patients tend to have autonomic dysfunction which influences the blood pressure and heart rate control as well as they have higher incidence of LV dysfunction.

- They also tend to have a greater proportion of ulcerated plaques on coronary angiography.

According to American Diabetes Association standards of care, the relationship of controlled blood glucose levels and reduced mortality in the setting of MI has been demonstrated. The American College of Endocrinology has also emphasized the importance of careful control of blood glucose targets in the range of 110 mg per dL preprandially to a maximum of 180 mg per dL.

The medical management of patients with diabetes who have UA/NSTEMI is the same and these patient should receive all the recommended medications unless contraindicated. Although beta blockers can mask the symptoms of hypoglycemia or lead to it by blunting the hyperglycemic response, they nevertheless should be used with appropriate caution in patients with diabetes mellitus and UA/NSTEMI.

Diabetes and Coronary Revascularization

Traditionally, CABG has been recommended over PCI as the choice for revascularization in patients with diabetes who have multivessel CAD.

Clinical Trial Data

- In the BARI trial in which outcomes for CABG in treated patients with diabetes were far better than those for PCI.

- A 9-year follow-up of the NHLBI registry[2] showed a similar disturbing pattern for patients with diabetes undergoing PCI. Immediate angiographic success and completeness of revascularization were similar, but compared with patients without diabetes, patients with diabetes (who again had more severe CAD and comorbidities) had increased rates of hospital mortality, nonfatal MI, death and MI, and the combined end point of death, MI, and CABG. At 9 years, rates of mortality, MI, repeat PCI, and CABG were all higher in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes.

- Perioperative hyperglycemia is an independent predictor of infection in patients with diabetes mellitus, with the lowest mortality in patients with blood glucose less than or equal to 150 mg per dL. Attainment of targeted glucose control in the setting of cardiac surgery is associated with reduced mortality and risk of deep sternal wound infections in cardiac surgery patients with diabetes.

- In a study with historical controls, the outcome after coronary stenting was superior to that after PTCA in patients with diabetes, and the restenosis rate after stenting was reduced. Three trials have shown that abciximab considerably improved the outcome of PCI in patients with diabetes.

To summarize, coronary artery bypass grafting, especially with 1 or both internal mammary arteries, leads to more complete revascularization and a decreased need for reintervention than PCI in diabetic patients with multivessel disease. Given the diffuse nature of diabetic coronary disease, the relative benefits of CABG over PCI may well persist for diabetic patients.

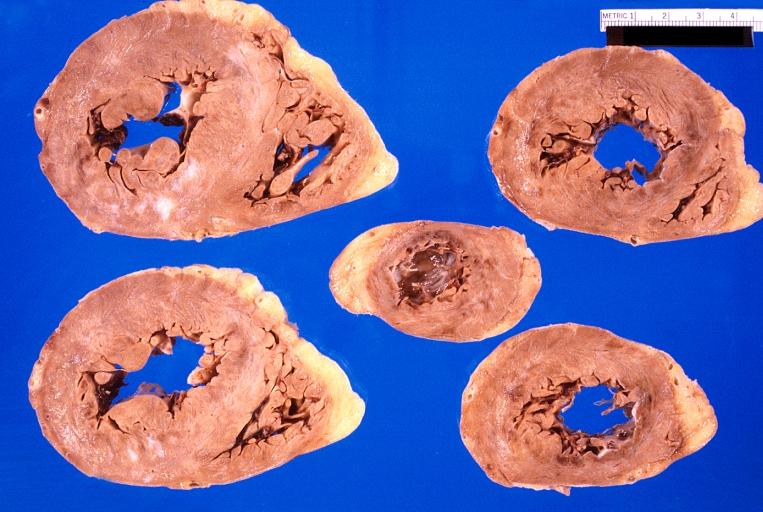

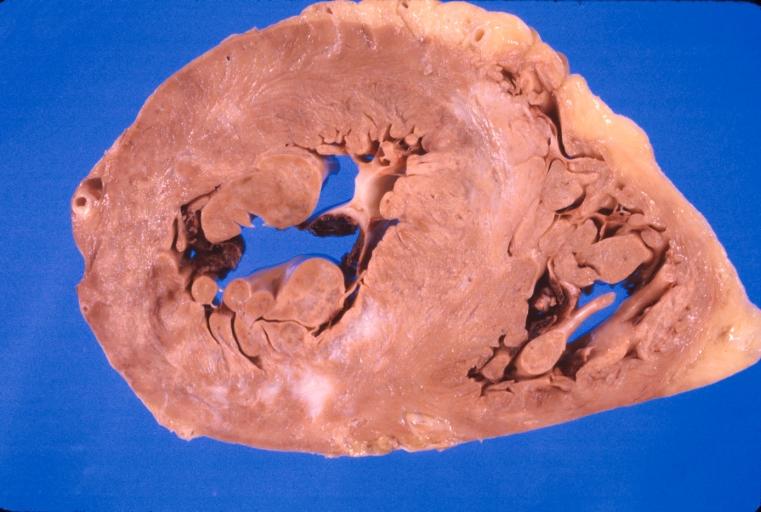

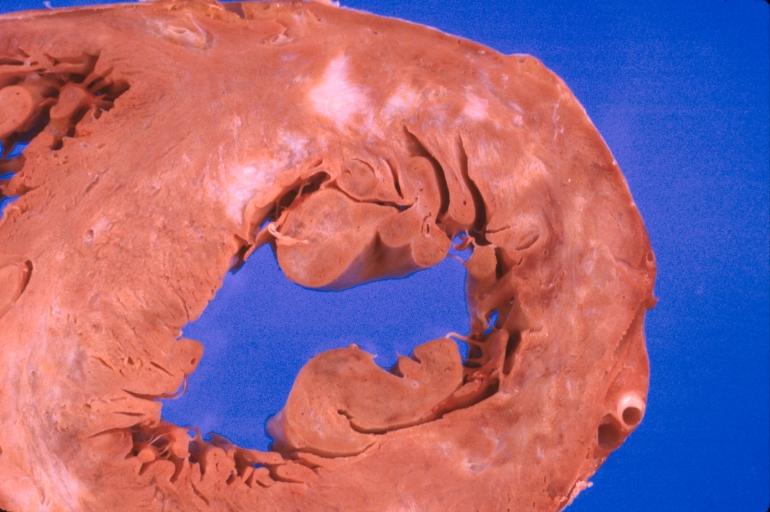

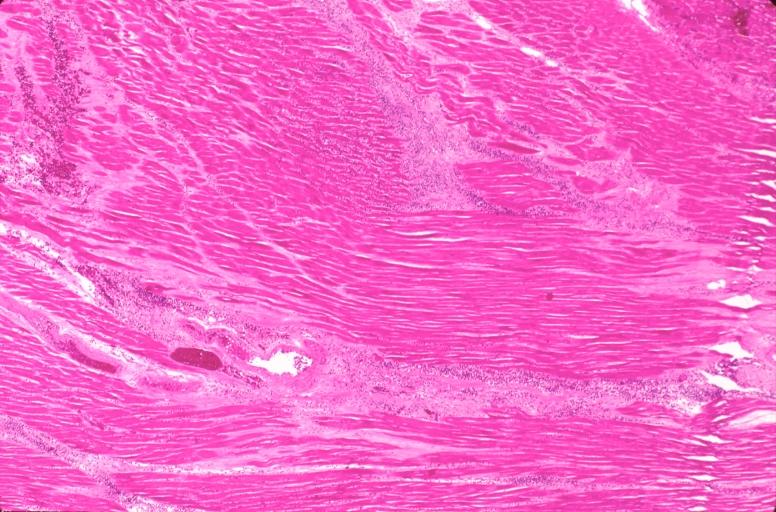

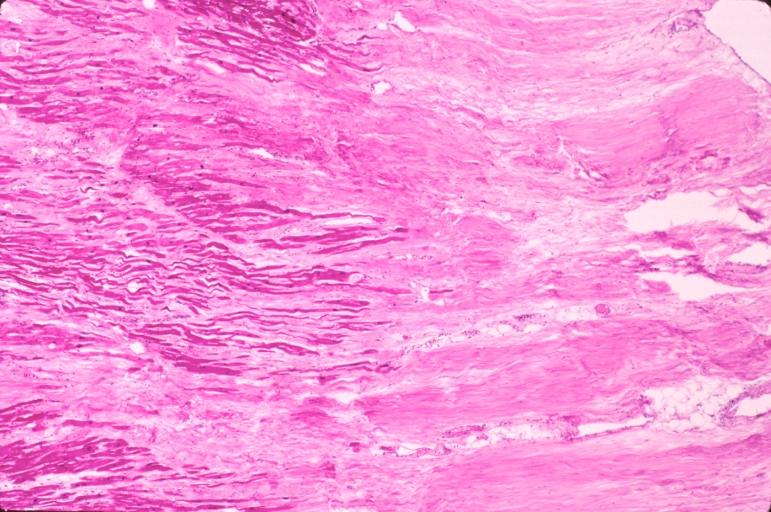

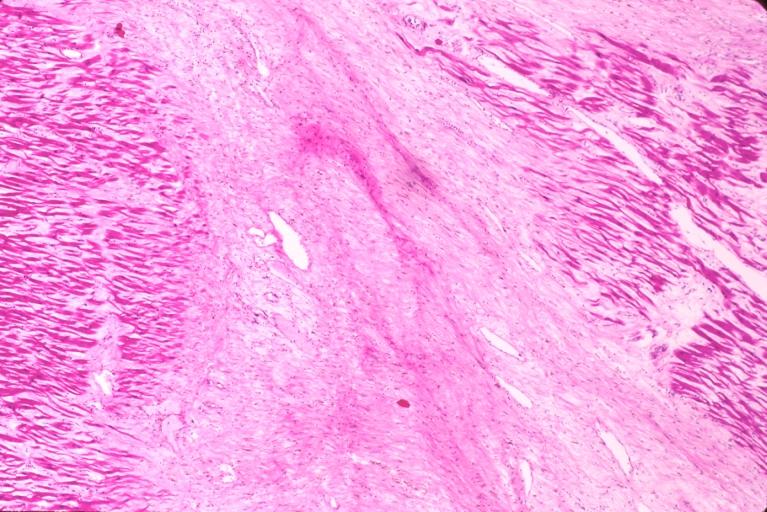

Pathology Findings

Images shown below are courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

-

Heart, acute myocardial infarction, 6 days old, in a patient with diabetes mellitus and hypertension

2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes (DO NOT EDIT) [3]

| Class I |

| "1. Medical treatment in the acute phase of NSTE-ACS and decisions to perform stress testing, angiography, and revascularization should be similar in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. (Level of Evidence: A)" |

2012 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline and Replacing the 2011 Focused Update) (DO NOT EDIT)[4]

Diabetes Mellitus (DO NOT EDIT)[4]

| Class I |

| "1. Medical treatment in the acute phase of UA/NSTEMI and decisions on whether to perform stress testing, angiography, and revascularization should be similar in patients with and without diabetes mellitus.[5][6][7][8] (Level of Evidence: A)" |

| Class IIa |

| "1. For patients with UA/NSTEMI and multivessel disease, CABG with use of the internal mammary arteries can be beneficial over PCI in patients being treated for diabetes mellitus.[9] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| "2. PCI is reasonable for UA/NSTEMI patients with diabetes mellitus with single-vessel disease and inducible ischemia.[5] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| "3. It is reasonable to use an insulin-based regimen to achieve and maintain glucose levels less than 180 mg/dL while avoiding hypoglycemia* for hospitalized patients with UA/NSTEMI with either a complicated or uncomplicated course.[10][11][12][13] (Level of Evidence: B)" |

| “ |

* There is uncertainty about the ideal target range for glucose necessary to achieve an optimal risk-benefit ratio. |

” |

References

- ↑ Malmberg K, Yusuf S, Gerstein HC; et al. (2000). "Impact of diabetes on long-term prognosis in patients with unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of the OASIS (Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes) Registry". Circulation. 102 (9): 1014–9. PMID 10961966. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Kip KE, Faxon DP, Detre KM, Yeh W, Kelsey SF, Currier JW (1996). "Coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty Registry". Circulation. 94 (8): 1818–25. PMID 8873655. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Ezra A. Amsterdam, MD, FACC; Nanette K. Wenger, MD et al.2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC. September 2014 (ahead of print)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 2012 Writing Committee Members. Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR; et al. (2012). "2012 ACCF/AHA Focused Update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2007 Guideline and Replacing the 2011 Focused Update): A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 126 (7): 875–910. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0. PMID 22800849.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Vicari R, Frey MJ, Lakkis N; et al. (2001). "Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban". N Engl J Med. 344 (25): 1879–87. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106213442501. PMID 11419424. Review in: ACP J Club. 2002 Jan-Feb;136(1):4

- ↑ "Invasive compared with non-invasive treatment in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre study. FRagmin and Fast Revascularisation during InStability in Coronary artery disease Investigators". Lancet. 354 (9180): 708–15. 1999. PMID 10475181.

- ↑ Antman EM, Cohen M, Radley D, McCabe C, Rush J, Premmereur J; et al. (1999). "Assessment of the treatment effect of enoxaparin for unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. TIMI 11B-ESSENCE meta-analysis". Circulation. 100 (15): 1602–8. PMID 10517730.

- ↑ Norhammar A, Malmberg K, Diderholm E, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Rydén L; et al. (2004). "Diabetes mellitus: the major risk factor in unstable coronary artery disease even after consideration of the extent of coronary artery disease and benefits of revascularization". J Am Coll Cardiol. 43 (4): 585–91. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.050. PMID 14975468.

- ↑ Chaitman BR, Hardison RM, Adler D, Gebhart S, Grogan M, Ocampo S; et al. (2009). "The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes randomized trial of different treatment strategies in type 2 diabetes mellitus with stable ischemic heart disease: impact of treatment strategy on cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction". Circulation. 120 (25): 2529–40. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913111. PMC 2830563. PMID 19920001.

- ↑ NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D; et al. (2009). "Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients". N Engl J Med. 360 (13): 1283–97. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. PMID 19318384. Review in: J Fam Pract. 2009 Aug;58(8):424-6 Review in: Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151(4):JC2-5

- ↑ Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Goyal A, Krumholz HM, Masoudi FA, Xiao L; et al. (2009). "Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction". JAMA. 301 (15): 1556–64. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.496. PMID 19366775.

- ↑ Malmberg K, Norhammar A, Wedel H, Rydén L (1999). "Glycometabolic state at admission: important risk marker of mortality in conventionally treated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: long-term results from the Diabetes and Insulin-Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) study". Circulation. 99 (20): 2626–32. PMID 10338454.

- ↑ Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I; et al. (2006). "Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU". N Engl J Med. 354 (5): 449–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052521. PMID 16452557. Review in: ACP J Club. 2006 Sep-Oct;145(2):34