Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;"|Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

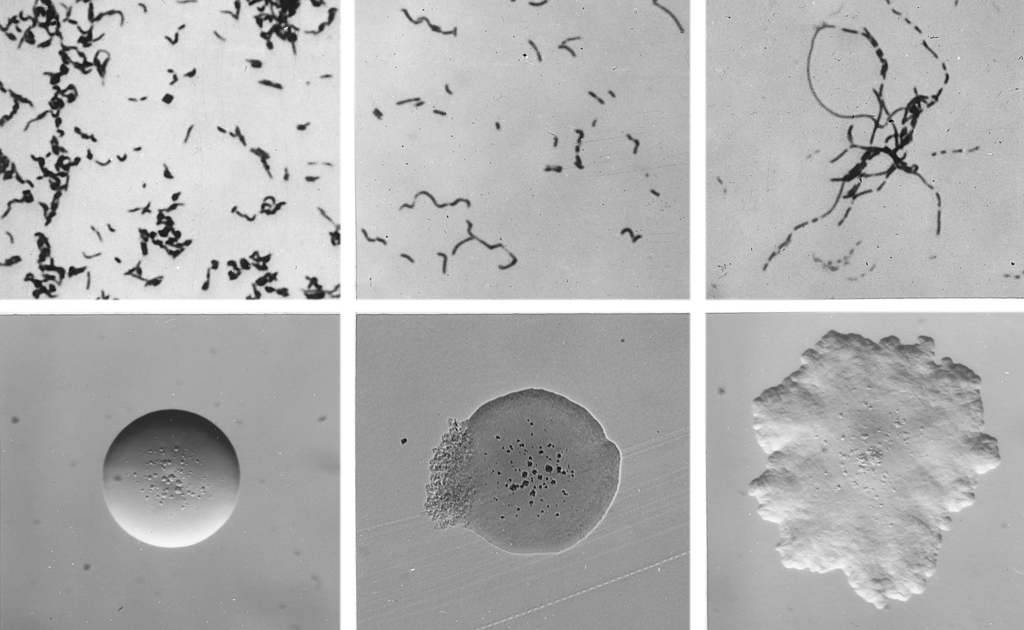

Cellular and colonial morphology of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

| ||||||||||||||

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;" | Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae Migula, 1900 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1];Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Kiran Singh, M.D. [2]

Overview

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is a Gram-positive, catalase-negative, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming, non-acid-fast, non-motile bacterium. The organism was first established as a human pathogen late in the nineteenth century.[1] It may be isolated from soil, food scraps and water contaminated by infected animals. It can survive in soil for several weeks. In pig faeces, the survival period of this bacterium ranges from 1 to 5 months.[2] It grows aerobically and anaerobically and does not contain endotoxin. Distributed worldwide, E. rhusiopathiae is primarily considered an animal pathogen, causing a disease known as erysipelas in animals (and erysipeloid in humans – see below). Turkeys and pigs are most commonly affected, but cases have been reported in other birds, sheep, fish, and reptiles.[3] In pigs, the disease is known as "diamond skin disease." The human disease called erysipelas is not caused by E. rhusiopathiae, but by various members of the genus Streptococcus. It is most frequently associated as an occupational disease of butchers.

Epidemiology

Erysipeloid is transmitted by several animals, particularly pigs, in which the disease (very common in the past) has several names (‘swine erysipelas’ in English, ‘rouget du porc’ in French and ‘mal rossino’ in Italian). Urticaria-like lesions, arthralgia⁄arthritis, endocarditis and sepsis are the most characteristic features of swine erysipelas. Other animals that can transmit the infection are sheep, rabbits, chickens, turkeys, ducks, emus, scorpion fish and lobsters. Erysipeloid is an occupational disease, mainly found in animal breeders, veterinarians, slaughterhouse workers, furriers, butchers, fishermen, fishmongers, housewives, cooks and grocers. One epidemic of erysipeloid was described in workers involved in manufacturing buttons from animal bone.[2] The disease is of greatest prevalence and economic importance.[clarification needed] It is economically detrimental to the pig industries of North America, Europe, Asia and Australia.[1] True erysipeloid is usually localized to the back of one hand and/or fingers. The palms, forearms, arms, face and legs are rarely involved.[2]

Selective Media

Traditionally, culture methods for the isolation of E. rhusiopathiae involve the use of selective and enrichment media. Commercially-available blood culture media are satisfactory for primary isolation from blood since E. rhusiopathiae is not particularly fastidious. A number of selective media for the isolation of Erysipelothrix have been described also. A commonly used medium is Erysipelothrix selective broth (ESB), a nutrient broth containing serum, tryptose, kanamycin, neomycin, and vancomycin . Modified blood azide medium (MBA) is a selective agar containing sodium azide and horse blood or serum. Packer’s medium is a selective medium for grossly contaminated specimens, which contains sodium azide and crystal violet. Bohm’s medium utilises sodium azide, kanamycin, phenol and water blue. Shimoji’s selective enrichment broth contains tryptic soy broth, Tween 80, Tris-aminomethane, crystal violet and sodium azide.[1]

Clinical Diseases

In humans, E. rhusiopathiae infections most commonly present in a mild cutaneous form known as erysipeloid.[3] Less commonly, it can result in sepsis; this scenario is often associated with endocarditis. Erysipeloid, also named in the past Rosenbach’s disease, Baker–Rosenbach disease and pseudoerysipelas, is a bacterial infection of the skin caused by traumatic penetration of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae.[2] It occurs most commonly as an occupational disease. The disease is characterized clinically by an erythematous oedema, with well-defined and raised borders, usually localized to the back of one hand and ⁄ or fingers. Vesicular, bullous and erosive lesions may also be present. The lesion may be asymptomatic or accompanied by mild pruritus, pain and fever.

Virulence Factors

Various virulence factors have been suggested as being involved in the pathogenicity of E. rhusiopathiae. The presence of a hyaluronidase and neuraminidase has been recognised, and it was shown that neuraminidase plays a significant role in bacterial attachment and subsequent invasion into host cells. The role of hyaluronidase in the disease process is controversial. The presence of a heat labile capsule has been reported as important in virulence.[1]

Laboratory Assays

Laboratory smears show Gram-positive rods (though Gram stain has low sensitivity for this microbe). It is non-motile, catalase-negative, microaerophilic, capnophilic, and non-spore-forming. It can also produce H2S (gas), which is a unique characteristic for a Gram-positive bacillus. Acid is produced from glucose, fructose, galactose and lactose but not from maltose, xylose, and mannitol. Sucrose is fermented by most strains of E. tonsillarum but not by E. rhusiopathiae. Hydrogen sulfide H2S is produced by 95% of strains of Erysipelothrix species as demonstrated on triple sugar iron (TSI) agar. E. rhusiopathiae can be differentiated from other Gram-positive bacilli, in particular, from Arcanobacterium (Corynebacterium) pyogenes and Arcanobacterium (Corynebacterium) haemolyticum, which are hemolytic on blood agar and do not produce hydrogen sulfide in TSI agar slants, and from Listeria monocytogenes, which is catalase positive, motile and is sensitive to neomycin. Rapid identification of E. rhusiopathiae can be achieved with the API Coryne System. It is a commercial strip system based on a number of biochemical reactions for the identification of coryneform bacteria and related genera, including E. rhusiopathiae. The system permits reliable and rapid identification of bacteria and has been considered to be a good alternative to traditional biochemical methods.[1] Laboratory investigations may reveal leucocytosis,slightly increased serum c-globulins and an increase in inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and a-1 acid glycoprotein).[2]

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Skin

Hand

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

-

Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]

Treatment

Penicillin is the treatment of choice for both disease states. It is resistant to vancomycin. E. rhusiopathiae is sensitive in vitro and in vivo mainly to penicillins but also to cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone), tetracyclines (chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, pefloxacin), clindamycin, erythromycin, imipenem and piperacillin. It is resistant to vancomycin, chloramphenicol, daptomycin, gentamicin, netilmicin, polymyxin B, streptomycin, teicoplanin, tetracycline and trimethoprim ⁄ sulfamethoxazole. Penicillins and cephalosporins are the first-line choice for treatment. A 7-day course is appropriate, and clinical improvement is usually observed 2–3 days after the beginning of the treatment.[2]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Q. Wang, B.J. Chang, Th.V. Riley (2010). "Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae". Journal of Veterinary Microbiology. 140: 405–417.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 S. Veraldi, V. Girgenti, F. Dassoni & R. Gianotti (2009). "Erysipeloid: a review". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 34: 859–862.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 C. Josephine Brooke & Thomas V. Riley (1999). "Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: bacteriology, epidemiology and clinical manifestations of an occupational pathogen". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 48 (9): 789–799. doi:10.1099/00222615-48-9-789. PMID 10482289.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Dermatology Atlas".

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/8/8f/Erysipeloid01.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/0/07/Erysipeloid02.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/a/a9/Erysipeloid03.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/9/9d/Erysipeloid04.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/7/72/Erysipeloid05.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/1/1c/Erysipeloid06.jpg)

![Erysipeloid. Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[4]](/images/6/6b/Erysipeloid07.jpg)