Cardiac surgery

|

WikiDoc Resources for Cardiac surgery |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Cardiac surgery Most cited articles on Cardiac surgery |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Cardiac surgery |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Cardiac surgery at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Cardiac surgery Clinical Trials on Cardiac surgery at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Cardiac surgery NICE Guidance on Cardiac surgery

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Cardiac surgery Discussion groups on Cardiac surgery Patient Handouts on Cardiac surgery Directions to Hospitals Treating Cardiac surgery Risk calculators and risk factors for Cardiac surgery

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Cardiac surgery |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Mohammed A. Sbeih, M.D.[2] Phone:617-849-2629

See also: Coronary artery bypass surgery

Overview

Cardiac surgery is surgery on the heart and/or great vessels performed by a cardiac surgeon. Frequently, it is done to treat complications of ischemic heart disease (for example, coronary artery bypass grafting), correct congenital heart disease, or treat valvular heart disease created by various causes including endocarditis. It also includes heart transplantation.

Historical Perspective

The earliest operations on the pericardium (the sac that surrounds the heart) took place in the 19th century and were performed by, among others,Francisco Romero,[1] Dominique Jean Larrey, Henry Dalton, and Daniel Hale Williams. The first successful surgery on the heart itself, performed without any complications, was by Dr. Ludwig Rehn of Frankfurt, Germany, who repaired a stab wound to the right ventricle on September 7, 1896.

Surgery on the great vessels (aortic coarctation repair, Blalock-Taussig shunt creation, closure of patent ductus arteriosus), became common after the turn of the century and falls in the domain of cardiac surgery, but technically cannot be considered heart surgery.

Closed heart surgery

Surgery on the great vessels was followed by the development of closed heart surgery, where the surgeon blindly worked on the beating heart. It left a great deal to be desired, but had much to offer for great risk. Palliation of severe mitral valve stenosis, which was common in the past due to rheumatic fever, could be accomplished by poking a finger into the (mitral) valve through an incision in the left atrium.[2] If a finger didn't do, a knife was passed through the incision to cut out tissue. Following successful treatment of mitral stenosis, a special cutter for aortic valve stenosis was developed, that maneuvered through an incision in the left atrium, accomplished much the same thing as the surgeon's finger in a stenosed mitral valve.

Operations under hypothermia

It was soon discovered that the repair of intracardiac pathologies required a bloodless and motionless environment, which means that the heart should be stopped and drained of blood. The first successful intracardiac correction of a congenital heart defect using hypothermia was performed by Dr. C. Walton Lillehei and Dr. F. John Lewis at the University of Minnesota on September 2, 1952. The following year, Soviet surgeon Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Vishnevskiy conducted the first cardiac surgery under local anesthesia.

Operations on the open heart

Surgeons realized the limitations of hypothermia - complex intracardiac repairs take more time and the patient needs blood flow to the body (and particularly the brain); the patient needs the function of the heart and lungs provided by an artificial method, hence the term cardiopulmonary bypass. Dr. John Heysham Gibbon at Jefferson Medical School in Philadelphia reported in 1953 the first successful use of extracorporeal circulation by means of an oxygenator, but he abandoned the method, disappointed by subsequent failures. In 1954 Dr. Lillehei realized a successful series of operations with the controlled cross-circulation technique in which the patient's mother or father was used as a 'heart-lung machine'. Dr. John W. Kirklin at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota started using a Gibbon type pump-oxygenator in a series of successful operations, and was soon followed by surgeons in various parts of the world.

Modern beating-heart surgery

Since the 1990s, surgeons have begun to perform Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery without the aforementioned cardiopulmonary bypass. In these operations, the heart is beating during surgery, but is stabilized to provide a (almost) still work area. Some researchers believe this approach results in fewer post-operative complications (such as postperfusion syndrome) and better overall results (studies results are controversial as of 2007, surgeon's preference and hospital results still play a major role).

Minimally invasive surgery

A new form of heart surgery that has grown in popularity is robotic heart surgery. This is where a machine (today by far and away the most popular is the da Vinci surgical system by Intuitive Surgical) is used to perform surgery while being controlled by the heart surgeon. The main advantage to this is the size of the incision made in the patient. Instead of a incision being at least big enough for the doctor to put his hands inside, it does not have to be bigger than 3 small holes for the robot's much smaller hands to get through. Also, a major advantage to the robot is the recovery time of a patient, instead of 6 months of recovery time, some patients have recovered and resumed playing athletics in a matter of weeks.

Risks

The development of cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass techniques has reduced the mortality rates of these surgeries to relatively low levels. For instance, repairs of congenital heart defects are currently estimated to have 4-6% mortality rates.[3][4]

A major concern with cardiac surgery is the incidence of neurological damage. Stroke occurs in 2-3% of all people undergoing cardiac surgery, and is higher in patients at risk for stroke. A more subtle constellation of neurocognitive deficits attributed to cardiopulmonary bypass is known as postperfusion syndrome (sometimes called 'pumphead'). The symptoms of postperfusion syndrome were initially felt to be permanent,[5] but were shown to be transient with no permanent neurological impairment.[6]

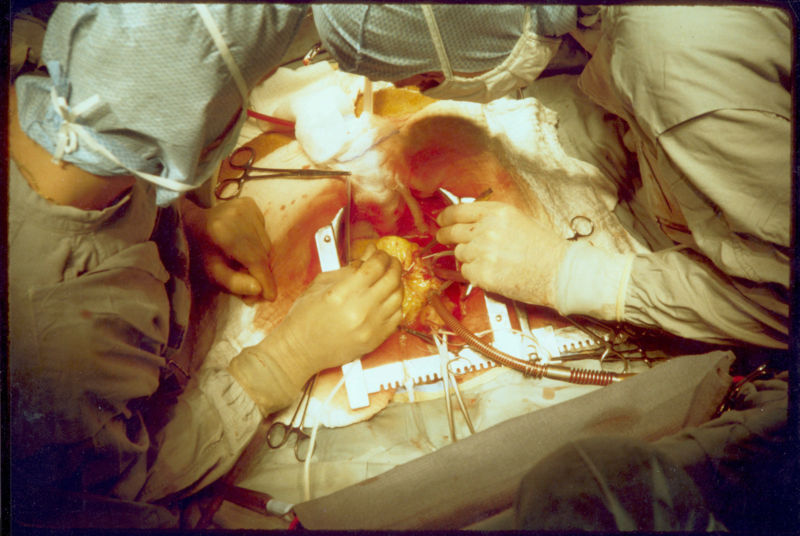

Images

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted

2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization (Please do not edit). CABG in Patients Undergoing Other Cardiac Surgery

| Class I |

| "1. In patients undergoing valve surgery, aortic surgery, or other cardiac operations who have significant CAD, CABG is recommended with the goal of reducing ischemic events. (Level of Evidence: C-LD) " |

| Class IIa |

| " 2. In patients undergoing valve surgery, aortic surgery, or other cardiac operations who have intermediate CAD, CABG may be reasonable with a goal of reducing ischemic events (Level of Evidence C-LD)". |

See also

References

- ↑ Aris A. Francisco Romero, the first heart surgeon. Ann Thorac Surg 1997 Sep;64(3):870-1. PMID 9307502

- ↑ Bigelow WG. Cold Hearts: The Story of Hypothermia and the Pacemaker in Heart Surgery. McClelland and Stewart Limited. 1984. ISBN 0-7710-1414-7.

- ↑ Stark J, Gallivan S, Lovegrove J, Hamilton JR, Monro JL, Pollock JC, Watterson KG. Mortality rates after surgery for congenital heart defects in children and surgeons' performance. Lancet 2000 March 18;355(9208):1004-7. PMID 10768449

- ↑ Klitzner TS, Lee M, Rodriguez S, Chang RR. Sex-related Disparity in Surgical Mortality among Pediatric Patients. Congenital Heart Disease 2006 May;1(3):77. Abstract

- ↑ Newman M, Kirchner J, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones R, Mark D, Reves J, Blumenthal J (2001). "Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery". N Engl J Med. 344 (6): 395–402. PMID 11172175.

- ↑ Van Dijk D, Jansen E, Hijman R, Nierich A, Diephuis J, Moons K, Lahpor J, Borst C, Keizer A, Nathoe H, Grobbee D, De Jaegere P, Kalkman C (2002). "Cognitive outcome after off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized trial". JAMA. 287 (11): 1405–12. PMID 11903027.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Correction to: 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 145 (11): e771. 2022. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001061. PMID 35286170 Check

|pmid=value (help).

Further reading

- [edited by] Lawrence H. Cohn, L. Henry Edmunds, Jr (2003). Cardiac surgery in the adult. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0-07-139129-0. Full text online

External links

- The American Heart Association

- "Congenital Heart Disease Surgical Corrective Procedures", a list of surgical procedures

- Minimally invasive heart surgery. Medical Encyclopedia, MedlinePlus.

- Heart Surgery USA - A summary of bypass surgery procedures.