Chlamydia trachomatis

|

Chlamydia infection Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Chlamydia trachomatis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

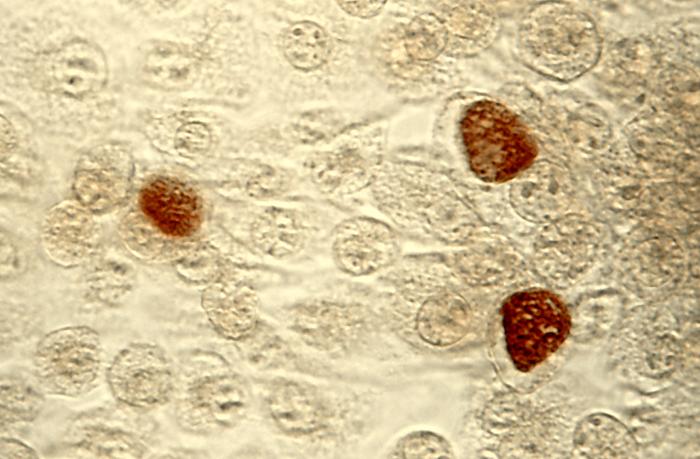

C. trachomatis inclusion bodies (brown) in a McCoy cell culture - Source: https://www.cdc.gov/

| ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||

|

Chlamydia muridarum

Chlamydophila pneumoniae |

To learn about other chlamydial infections caused by species other than C. trachomatis, click here.

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aysha Anwar, M.B.B.S[2]

Overview

- Chlamydia trachomatis, an obligate intracellular human pathogen, is one of four bacterial species in the genus Chlamydia.[1]

- C. trachomatis is a Gram-negative bacterium, therefore its cell wall components retain the counter-stain safranin and appear pink under a light microscope.[2] It is ovoid in shape.[3]

- C. trachomatis includes three human biovars, based on variations in the major outer membrane protein (MOMP):

- serovars Ab, B, Ba, or C — cause trachoma: infection of the eyes, which can lead to blindness

- serovars D-K — cause urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, neonatal pneumonia, and neonatal conjunctivitis

- serovars L1, L2 and L3 — lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV)[4]

- The L2 serovar can be further differentiated into L2, L2', L2a, and L2b based on significant amino acid differences[5]

- Chlamydia can exchange DNA between its different strains, thus the evolution of new strains is common.[7]

Identification

Chlamydia species are readily identified and distinguished from other Chlamydia species using DNA-based tests.

Most strains of C. trachomatis are recognized by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to epitopes in the VS4 region of MOMP.[8] However, these mAbs may also cross-react with two other Chlamydia species, C. suis and C. muridarum.

Life-cycle

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens, which means they are unable to replicate outside of a host cell. However, to facilitate effective dissemination, these pathogens have evolved a distinct biphasic life cycle wherein they alternate between two functionally and morphologically distinct forms.

- The elementary body (EB) is infectious, but metabolically inert (much like a spore), and can survive for limited amounts of time in the extracellular milieu. Once the EB attaches to a susceptible host cell, it mediates its own internalization through pathogen-specified mechanisms (via type III secretion system) that allows for the recruitment of actin with subsequent engulfment of the bacterium.

- The internalized EB, within a membrane-bound compartment, immediately begins differentiation into the reticulate body (RB). RBs are metabolically active but non-infectious, and in many regards, resemble normal replicating bacteria. The intracellular bacteria rapidly modifies its membrane-bound compartment into the so-called chlamydial inclusion so as to prevent phagosome-lysosome fusion. The inclusion is thought to have no interactions with the endocytic pathway and apparently inserts itself into the exocytic pathway as it retains the ability to intercept sphingomyelin-containing vesicles.

- The mechanism by which the host cell protein is trafficked to the inclusion through the exocytic pathway is not fully understood. As the RBs replicate, the inclusion grows as well to accommodate the increasing numbers of organisms. Through unknown mechanisms, RBs begin a differentiation program back to the infectious EBs, which are released from the host cell to initiate a new round of infection. Because of their obligate intracellular nature, Chlamydiae have no tractable genetic system, unlike E. coli, which makes Chlamydiae and related organisms difficult to investigate.

Diseases caused by Chlamydia trachomatis

Chlamydia trachomatis can cause the following conditions:[9][10][11][12]

- Cervicitis

- Conjunctivitis

- Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Pneumonia in infants

- Reactive arthritis

- Urethritis

- Rectal infection (proctitis)

- Prostatitis

- Ectopic pregnancy

Gallery

-

Photomicrograph of Chlamydia trachomatis taken from a urethral scrape. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]

-

McCoy cell monolayers with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion bodies (200X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]

-

McCoy cell monolayers with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion bodies (50X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]

-

Photomicrograph depicts HeLa cells infected with Type-A Chlamydia trachomatis (400X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]

-

Patient’s left eye with the upper lid retracted in order to reveal the inflamed conjunctival membrane lining the inside of both the upper and lower lids, due to what was determined to be a case of inclusion conjunctivitis caused by the bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 463–70. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ "Chlamydia". MicrobeWiki. Department of Biology, Kenyon College. 2006-08-15. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M (September 2013). "Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update". Indian J. Med. Res. 138 (3): 303–16. PMC 3818592. PMID 24135174.

- ↑ Fredlund H, Falk L, Jurstrand M, Unemo M (2004). "Molecular genetic methods for diagnosis and characterisation of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: impact on epidemiological surveillance and interventions". APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 112 (11–12): 771–84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11211-1205.x. PMID 15638837.

- ↑ Ceovic R, Gulin SJ (2015). "Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges". Infect Drug Resist. 8: 39–47. doi:10.2147/IDR.S57540. PMC 4381887. PMID 25870512.

- ↑ Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Crane DD; et al. (June 2008). "The Chlamydia trachomatis Plasmid Is a Transcriptional Regulator of Chromosomal Genes and a Virulence Factor". Infection and immunity. 76 (6): 2273–83. doi:10.1128/IAI.00102-08. PMC 2423098. PMID 18347045.

- ↑ Harris SR, Clarke IN, Seth-Smith HM; et al. (April 2012). "Whole-genome analysis of diverse Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies phylogenetic relationships masked by current clinical typing". Nat. Genet. 44 (4): 413–9, S1. doi:10.1038/ng.2214. PMC 3378690. PMID 22406642.

- ↑ Ortiz L, Angevine M, Kim SK, Watkins D, DeMars R (2000). "T-Cell Epitopes in Variable Segments of Chlamydia trachomatis Major Outer Membrane Protein Elicit Serovar-Specific Immune Responses in Infected Humans". Infect. Immun. 68 (3): 1719–23. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.3.1719-1723.2000. PMC 97337. PMID 10678996.

- ↑ Paroli E, Franco E (1990). "[Oculogenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis]". Recenti Prog Med. 81 (7–8): 539–48. PMID 2247702.

- ↑ Holstege G, van Ham JJ, Tan J (1986). "Afferent projections to the orbicularis oculi motoneuronal cell group. An autoradiographical tracing study in the cat". Brain Res. 374 (2): 306–20. PMID 3719340.

- ↑ Feltham N, Fahey D, Knight E (1987). "A growth inhibitory protein secreted by human diploid fibroblasts. Partial purification and characterization". J Biol Chem. 262 (5): 2176–9. PMID 3818592.

- ↑ Peipert JF (2003). "Clinical practice. Genital chlamydial infections". N Engl J Med. 349 (25): 2424–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp030542. PMID 14681509.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

Further reading

Bellaminutti, Serena; Seracini, Silva; De Seta, Francesco; Gheit, Tarik; Tommasino, Massimo; Comar, Manola (November 2014). "HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis Co-Detection in Young Asymptomatic Women from High Incidence Area for Cervical Cancer". Journal of Medical Virology. 86 (11): 1920–1925. doi:10.1002/jmv.24041. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

External links

- Chlamydiae.com

- Template:GPnotebook

- "Chlamydia trachomatis". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 813.

![Photomicrograph of Chlamydia trachomatis taken from a urethral scrape. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/2/21/Chlamydia15.jpeg)

![McCoy cell monolayers with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion bodies (200X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/8/88/Chlamydia11.jpeg)

![McCoy cell monolayers with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion bodies (50X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/e/e2/Chlamydia10.jpeg)

![Photomicrograph depicts HeLa cells infected with Type-A Chlamydia trachomatis (400X mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/2/29/Chlamydia09.jpeg)

![Patient’s left eye with the upper lid retracted in order to reveal the inflamed conjunctival membrane lining the inside of both the upper and lower lids, due to what was determined to be a case of inclusion conjunctivitis caused by the bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/3/3c/Chlamydia03.jpeg)

![From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [13]](/images/0/01/Chlamydia04.jpeg)