Chlamydophila pneumoniae

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Chlamydia pneumoniae (also suggested as Chlamydophila pneumoniae) is a species of chlamydiae bacteria that infects humans and is a major cause of pneumonia. Chlamydia pneumoniae has a complex life cycle and must infect another cell in order to reproduce and thus is classified as an obligate intracellular pathogen. In addition to its role in pneumonia, there is evidence associating Chlamydia pneumoniae with atherosclerosis and with asthma. The full genome sequence for Chlamydia pneumoniae was published in 1999.

Chlamydia pneumoniae also infects and causes disease in Koalas, emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus), iguanas, chameleons, frogs, and turtles.

Life Cycle and Method of Infection

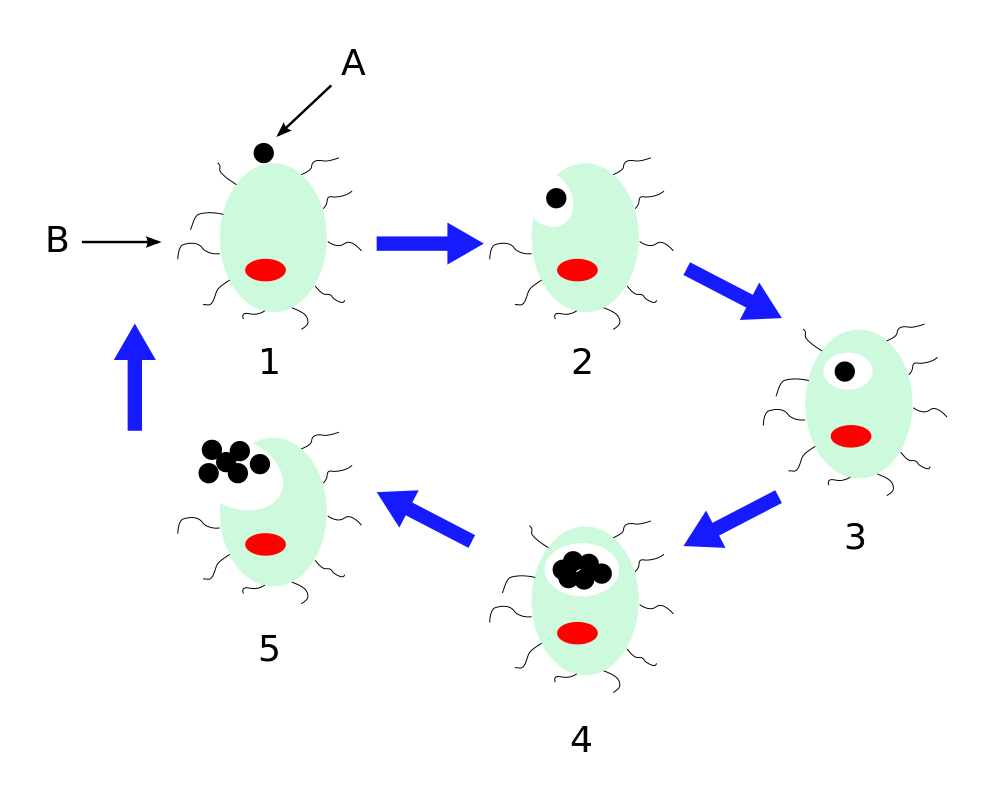

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a small bacterium (0.2 to 1 micrometer) that undergoes several transformations during its life cycle. It exists as an elementary body (EB) in between hosts. The EB is not biologically active but is resistant to environmental stresses and can survive outside of a host for a limited time. The EB travels from an infected person to the lungs of a non-infected person in small droplets and is responsible for infection. Once in the lungs, the EB is taken up by cells in a pouch called an endosome by a process called phagocytosis. However, the EB is not destroyed by fusion with lysosomes as is typical for phagocytosed material. Instead, it transforms into a reticulate body and begins to replicate within the endosome. The reticulate bodies must utilize some of the host's cellular machinery to complete its replication. The reticulate bodies then convert back to elementary bodies and are released back into the lung, often after causing the death of the host cell. The EBs are thereafter able to infect new cells, either in the same organism or in a new host. Thus, the life cycle of Chlamydia pneumoniae is divided between the elementary body which is able to infect new hosts but can not replicate and the reticulate body which replicates but is not able to cause new infection.

Pneumonia Caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common cause of pneumonia around the world. Chlamydia pneumoniae is typically acquired by otherwise healthy people and is a form of community-acquired pneumonia. Because treatment and diagnosis are different from historically recognized causes such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumonia caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae is categorized as an "atypical pneumonia."

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms of infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae are indistinguishable from other causes of pneumonia. These include cough, fever, and difficulties breathing. Chlamydia pneumoniae more often causes pharyngitis, laryngitis, and sinusitis than other causes of pneumonia; however, because many other causes of pneumonia results in these symptoms, differentiation is not possible. Likewise, a physical examination by a health provider does not typically provide information which allows for a definite diagnosis.

Diagnosis of Chlamydia pneumoniae may be confounded by prior infections with this microorganism. Examination of sputum or the secretions of the respiratory tract may reveal signs of the bacteria. Otherwise, examination of the blood may reveal antibodies against the bacteria. If there has been a prior infection, this may have resulting in pre-existing antibodies. Therefore, interpretation may require a period of six weeks in order to reanalyze the antibodies and to determine whether the infection was new or old. Examination of the blood may also show proteins (antigens) from Chlamydia pneumoniae, either through direct fluorescent antibody testing, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Chest x-rays of lungs infected with Chlamydia pneumoniae often show a small patch of increased shadow (opacity). However, many different patterns are common and there is no appearance which allows for a specific diagnosis.

Treatment and Prognosis

Typically, treatment for pneumonia is begun before the causative microorganism is identified. This empiric therapy includes an antibiotic active against the atypical bacteria, including Chlamydia pneumoniae. The most common type of antibiotic used is a macrolide such as azithromycin or clarithromycin. If testing reveals that Chlamydia pneumoniae is the causative agent, therapy may be switched to doxycycline, which is slightly more effective against the bacteria. Sometimes a quinolone antibiotic such as levofloxacin may be started empirically. This group is not as effective against Chlamydia pneumoniae. Treatment is typically continued for ten to fourteen days for known infections.

Prognosis of pneumonia caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae is excellent. Hospitalization is uncommon, complications are rare, and most people have no residual deficits. In fact, Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common cause of walking pneumonia, so named because most people are able to continue to walk and participate in reduced activity during infection.

Epidemiology and Prevention

Chlamydia pneumoniae affects all age groups and is most common among the 60-79 year old age group. Reinfection is common after a short period of immunity. The incidence is one case out of one thousand per year and causes ten percent of community-acquired pneumonias treated without hospitalization.[citation needed] As of 2005, there are no vaccines or other ways to prevent infection other than good hygiene and healthy eating as well as active lifestyle some people with obesity face the same symptoms, a stress free life as well as active and conscious living are the best viral and physical prevention known.

Other Illnesses Caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae

In addition to pneumonia, Chlamydia pneumoniae less commonly causes several other illnesses. Among these are meningoencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord), arthritis, myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (inflammation of the nerves). It has also been associated with dozens of other conditions, such as Alzheimer's, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Prostatitis, and many others.

Links Between Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases

In addition to acute infections already covered, Chlamydia pneumoniae has been implicated in several chronic diseases. There is evidence that the onset of asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease of the lungs, is associated with infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. [citation needed] Some patients have had amazing recoveries from lifelong asthma as the result of being prescribed anti-chlamydial antibiotics.[citation needed] However, not all asthma results from infection with chlamydia pneumoniae, and research is ongoing.

Links between infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae heart attacks (myocardial infarction) and atherosclerosis have also been found (Blasi, F et al. 1996). In fact, Chlamydia pneumoniae has been found within plaques in the walls of coronary arteries supplying the heart (Ramirez, J et al. 1996; Jackson, L. A., et al. 1997). Antibody levels against Chlamydia pneumoniae are also higher in people with heart problems (Danesh, J., et al. 1997). As of 2005, short-term prescription of anti-chlamydial antibiotics has not been shown to decrease incidence of myocardial infarction.[citation needed]

Such treatment is experimental, although research from Vanderbilt as early as the mid 1990s found that chlamydophila pneumoniae had a role in many chronic inflammatory diseases [citation needed] and that multi-antibiotic protocols could be helpful, or even 'cure' some individuals with conditions such as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.[citation needed]

Chlamydia pneumoniae has also been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis,[citation needed] a controversial finding, but pilot data suggests that antibiotic treatment of MS results in improvements, sometimes dramatic, in such cases.[citation needed] A range of other inflammatory conditions are hypothesized to be linked with infection with chlamydial pneumonaie, including fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, intercystial cystitis and prostatitis, as well as many others.

Treatment

Antimicrobial Regimen

- 1. Atypical pneumonia [1]

- 1.1 Adult

- Preferred regimen (1): Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 14-21 days

- Preferred regimen (2): Tetracycline 250 mg PO qid for 14-21 days

- Preferred regimen (3): Azithromycin 500 mg PO as a single dose, followed by 250 mg PO qd for 4 days

- Preferred regimen (4): Clarithromycin 500 mg PO bid for 10 days

- Preferred regimen (5): Levofloxacin 500 mg IV OR PO qd for 7 to 14 days

- Preferred regimen (6): Moxifloxacin 400 mg PO qd for 10 days.

- 1.2 Pediatric

- Preferred regimen (1): Erythromycin suspension PO 50 mg/kg/day for 10 to 14 days

- Preferred regimen (2): Clarithromycin suspension PO 15 mg/kg/day for 10 days

- Preferred regimen (3): Azithromycin suspension PO 10 mg/kg once on the first day, followed by 5 mg/kg qd daily for 4 days

- 2. Upper respiratory tract infection[2]

- 2.1 Bronchitis

- Antibiotic therapy for C. pneumoniae is not required.

- 2.2 Pharyngitis

- Antibiotic therapy for C. pneumoniae is not required.

- 2.3 Sinusitis

- Antibiotic therapy is advisable if symptoms remain beyond 7-10 days.

References

- Bodetti TJ, Jacobson E, Wan C, Hafner L, Pospischil A, Rose K, Timms P. Molecular evidence to support the expansion of the hostrange of Chlamydophila pneumoniae to include reptiles as well as humans, horses, koalas and amphibians. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2002 Apr;25(1):146-52.

- Blasi F, Denti F, Erba M, Cosentini R, Raccanelli R, Rinaldi A, Fagetti L, Esposito G, Ruberti U, Allegra L. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae but not Helicobacter pylori in Atherosclerotic Plaques of Aortic Aneurysms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996 Nov;34(11):2766-2769.

- Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Grayston JT, Muhlestein B, Giugliano RP, Cairns R, Skene AM; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Antibiotic treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 21;352(16):1646-54.

- Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Chronic infections and coronary heart disease: is there a link? Lancet 1997;350:430-6.

- Hahn DL, Dodge RW, Golubjatnikov R. Association of Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) infection with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis and adult-onset asthma. JAMA 1991 266:225-30.

- Jackson LA, Campbell LA, Kuo C-C, Lee A, Grayston JT. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from a carotid endarterectomy specimen. J Infect Dis 1997;176:292-5.

- Jacobson ER, Heard D, Andersen A. Identification of Chlamydophila pneumoniae in an emerald tree boa, Corallus caninus.J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004 Mar;16(2):153-4.

- Kalman, S et al. 1999. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nature Genetics 21:385-389

- Mattson, M 2004. Infectious agents and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. "Aging Research Reviews" 3:105-120

- O'Connor S, et al. Potential Infectious Etiologies of Atherosclerosis: A Multifactorial Perspective. Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol 7, Sept-Oct 2001

- Ramirez J, Ahkee A, Ganzel BL, Ogden LL, Gaydos CA, Quinn TC, et al. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae (C pn) from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:979-82.

- Storey C, Lusher M, Yates P, Richmond S. Evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae of non-human origin. J Gen Microbiol. 1993 Nov;139(11):2621-6.

- Thomas NS, Lusher M, Storey CC, Clarke IN. Plasmid diversity in Chlamydia. Microbiology. 1997 Jun;143 ( Pt 6):1847-54.

External Links

- http://cpnhelp.org CPNhelp.org, A Clearinghouse for Information on Treatment of CPn Infections, especially those believed to be associated with chronic and disabling diseases such as MS and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Includes dozens of scientific papers, input from physicians who treat CPn infections, links to patents, and a forum to communicate with patients currently going through treatment of CPn infection through multi-antibiotic protocols.

- http://fpnotebook.com/LUN24.htm "Family Practice Notebook" page on Chlamydia pneumoniae

- ↑ Bennett, John (2015). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1455748013.

- ↑ Bartlett, John (2012). Johns Hopkins ABX guide : diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1449625580.