Atovaquone proguanil clinical pharmacology

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Chetan Lokhande, M.B.B.S [2]

Clinical Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

The constituents of MALARONE, atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride, interfere with 2 different pathways involved in the biosynthesis of pyrimidines required for nucleic acid replication. Atovaquone is a selective inhibitor of parasite mitochondrial electron transport. Proguanil hydrochloride primarily exerts its effect by means of the metabolite cycloguanil, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor. Inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase in the malaria parasite disrupts deoxythymidylate synthesis.

Pharmacodynamics

No trials of the pharmacodynamics of MALARONE have been conducted.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Atovaquone is a highly lipophilic compound with low aqueous solubility. The bioavailability of atovaquone shows considerable inter‑individual variability.

Dietary fat taken with atovaquone increases the rate and extent of absorption, increasing AUC 2 to 3 times and Cmax 5 times over fasting. The absolute bioavailability of the tablet formulation of atovaquone when taken with food is 23%. MALARONE Tablets should be taken with food or a milky drink.

Distribution

Atovaquone is highly protein bound (>99%) over the concentration range of 1 to 90 mcg/mL. A population pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated that the apparent volume of distribution of atovaquone (V/F) in adult and pediatric patients after oral administration is approximately 8.8 L/kg.

Proguanil is 75% protein bound. A population pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated that the apparent V/F of proguanil in adult and pediatric patients >15 years of age with body weights from 31 to 110 kg ranged from 1,617 to 2,502 L. In pediatric patients ≤15 years of age with body weights from 11 to 56 kg, the V/F of proguanil ranged from 462 to 966 L.

In human plasma, the binding of atovaquone and proguanil was unaffected by the presence of the other.

Metabolism

In a study where 14C‑labeled atovaquone was administered to healthy volunteers, greater than 94% of the dose was recovered as unchanged atovaquone in the feces over 21 days. There was little or no excretion of atovaquone in the urine (less than 0.6%). There is indirect evidence that atovaquone may undergo limited metabolism; however, a specific metabolite has not been identified. Between 40% to 60% of proguanil is excreted by the kidneys. Proguanil is metabolized to cycloguanil (primarily via CYP2C19) and 4-chlorophenylbiguanide. The main routes of elimination are hepatic biotransformation and renal excretion.

Elimination

The elimination half‑life of atovaquone is about 2 to 3 days in adult patients.

The elimination half‑life of proguanil is 12 to 21 hours in both adult patients and pediatric patients, but may be longer in individuals who are slow metabolizers.

A population pharmacokinetic analysis in adult and pediatric patients showed that the apparent clearance (CL/F) of both atovaquone and proguanil are related to the body weight. The values CL/F for both atovaquone and proguanil in subjects with body weight ≥11 kg are shown in Table 4.

|

The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone and proguanil in patients with body weight below 11 kg have not been adequately characterized.

Pediatrics

The pharmacokinetics of proguanil and cycloguanil are similar in adult patients and pediatric patients. However, the elimination half‑life of atovaquone is shorter in pediatric patients (1 to 2 days) than in adult patients (2 to 3 days). In clinical trials, plasma trough concentrations of atovaquone and proguanil in pediatric patients weighing 5 to 40 kg were within the range observed in adults after dosing by body weight.

Geriatrics

In a single‑dose study, the pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil were compared in 13 elderly subjects (age 65 to 79 years) to 13 younger subjects (age 30 to 45 years). In the elderly subjects, the extent of systemic exposure (AUC) of cycloguanil was increased (point estimate = 2.36, 90% CI = 1.70, 3.28). Tmax was longer in elderly subjects (median 8 hours) compared with younger subjects (median 4 hours) and average elimination half‑life was longer in elderly subjects (mean 14.9 hours) compared with younger subjects (mean 8.3 hours).

Renal Impairment

In patients with mild renal impairment (creatinine clearance 50 to 80 mL/min), oral clearance and/or AUC data for atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil are within the range of values observed in patients with normal renal function (creatinine clearance >80 mL/min). In patients with moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30 to 50 mL/min), mean oral clearance for proguanil was reduced by approximately 35% compared with patients with normal renal function (creatinine clearance >80 mL/min) and the oral clearance of atovaquone was comparable between patients with normal renal function and mild renal impairment. No data exist on the use of MALARONE for long-term prophylaxis (over 2 months) in individuals with moderate renal failure. In patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min), atovaquone Cmax and AUC are reduced but the elimination half‑lives for proguanil and cycloguanil are prolonged, with corresponding increases in AUC, resulting in the potential of drug accumulation and toxicity with repeated dosing [see Contraindications ].

Hepatic Impairment

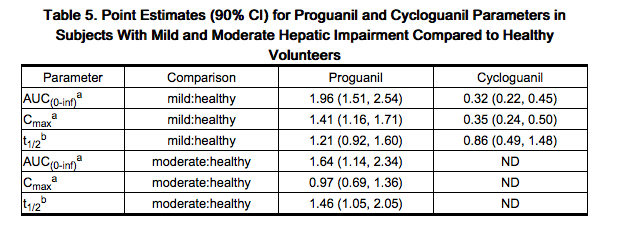

In a single‑dose study, the pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil were compared in 13 subjects with hepatic impairment (9 mild, 4 moderate, as indicated by the Child‑Pugh method) to 13 subjects with normal hepatic function. In subjects with mild or moderate hepatic impairment as compared to healthy subjects, there were no marked differences (<50%) in the rate or extent of systemic exposure of atovaquone. However, in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment, the elimination half‑life of atovaquone was increased (point estimate = 1.28, 90% CI = 1.00 to 1.63). Proguanil AUC, Cmax, and its elimination half-life increased in subjects with mild hepatic impairment when compared to healthy subjects (Table 5). Also, the proguanil AUC and its elimination half-life increased in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment when compared to healthy subjects. Consistent with the increase in proguanil AUC, there were marked decreases in the systemic exposure of cycloguanil (Cmax and AUC) and an increase in its elimination half‑life in subjects with mild hepatic impairment when compared to healthy volunteers (Table 5). There were few measurable cycloguanil concentrations in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment. The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone, proguanil, and cycloguanil after administration of MALARONE have not been studied in patients with severe hepatic impairment.

|

ND = not determined due to lack of quantifiable data. a Ratio of geometric means. b Mean difference.

Drug Interactions

There are no pharmacokinetic interactions between atovaquone and proguanil at the recommended dose.

- Atovaquone is highly protein bound (>99%) but does not displace other highly protein‑bound drugs in vitro.

- Proguanil is metabolized primarily by CYP2C19. Potential pharmacokinetic interactions between proguanil or cycloguanil and other drugs that are CYP2C19 substrates or inhibitors are unknown.

- Rifampin/Rifabutin: Concomitant administration of rifampin or rifabutin is known to reduce atovaquone concentrations by approximately 50% and 34%, respectively. The mechanisms of these interactions are unknown.

- Tetracycline: Concomitant treatment with tetracycline has been associated with approximately a 40% reduction in plasma concentrations of atovaquone.

- Metoclopramide: Concomitant treatment with metoclopramide has been associated with decreased bioavailability of atovaquone.

- Indinavir: Concomitant administration of atovaquone (750 mg twice daily with food for 14 days) and indinavir (800 mg three times daily without food for 14 days) did not result in any change in the steady‑state AUC and Cmax of indinavir but resulted in a decrease in the Ctrough of indinavir (23% decrease [90% CI = 8%, 35%]).[1]

References

Adapted from the FDA Package Insert.