Smoking cessation: Difference between revisions

Usama Talib (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Tarek Nafee (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{SI}} | |||

{{CMG}};{{AE}}{{SMP}},{{USAMA}},{{AKI}} | {{CMG}};{{AE}}{{SMP}},{{USAMA}},{{AKI}} | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

Revision as of 12:49, 31 May 2017

|

WikiDoc Resources for Smoking cessation |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Smoking cessation Most cited articles on Smoking cessation |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Smoking cessation |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Cochrane Collaboration on Smoking cessation |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Smoking cessation at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Smoking cessation Clinical Trials on Smoking cessation at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Smoking cessation NICE Guidance on Smoking cessation

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Smoking cessation Discussion groups on Smoking cessation Patient Handouts on Smoking cessation Directions to Hospitals Treating Smoking cessation Risk calculators and risk factors for Smoking cessation

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Smoking cessation |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1];Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [2],Usama Talib, BSc, MD [3],Aravind Kuchkuntla, M.B.B.S[4]

Overview

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States. Each year, nearly half a million Americans die prematurely of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke and 16 million live with a serious illness caused by smoking. Smoking can cause repairable damage to various organs including the heart, lungs, kidneys, stomach and intestines. Smoking is associated with the causation of various cancers in the humans. Quitting smoking cuts cardiovascular risks, reduces risk for stroke to about half that of a nonsmoker’s, reduces risks for cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, and bladder by half within 5 years and ten years after quitting smoking, the risk for lung cancer drops by half. Smoking cessation can be achieved by some general, non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies.

Epidemiology

- Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States, accounting for more than 480,000 deaths every year, or 1 of every 5 deaths.[1]

- In 2015, about 15 of every 100 U.S. adults aged 18 years or older (15.1%) currently smoked cigarettes, this means an estimated 36.5 million adults in the United States currently smoke cigarettes.

- Current smoking has declined from nearly 21 of every 100 adults (20.9%) in 2005 to about 15 of every 100 adults (15.1%) in 2015.

- Nearly 40 million US adults still smoke cigarettes, and about 4.7 million middle and high school students use at least one tobacco product, including e-cigarettes.

- Every day, more than 3,800 youth younger than 18 years smoke their first cigarette.

- Each year, nearly half a million Americans die prematurely of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke and more than 16 million Americans live with a smoking-related disease.

- Each year, the United States spends nearly $170 billion on medical care to treat smoking-related disease in adults.

The epidemiology of the current smoking status based on different descriptive characteristics is as follows:

Gender

- Nearly 17 of every 100 adult men (16.7%).

- More than 13 of every 100 adult women (13.6%).

Age

- 13 of every 100 adults aged 18–24 years (13.0%).

- Nearly 18 of every 100 adults aged 25–44 years (17.7%)

- 17 of every 100 adults aged 45–64 years (17.0%).

- More than 8 of every 100 adults aged 65 years and older (8.4%).

Race

- Nearly 22 of every 100 non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (21.9%).

- More than 20 of every 100 non-Hispanic multiple race individuals (20.2%).

- Nearly 17 of every 100 non-Hispanic Blacks (16.7%).

- More than 16 of every 100 non-Hispanic Whites (16.6%).

- More than 10 of every 100 Hispanics (10.1%).

- 7 of every 100 non-Hispanic Asians* (7.0%).

Education

- More than 24 of every 100 adults with 12 or fewer years of education (no diploma) (24.2%).

- About 34 of every 100 adults with a GED certificate (34.1%).

- Nearly 20 of every 100 adults with a high school diploma (19.8%).

- More than 18 of every 100 adults with some college (no degree) (18.5%).

- More than 16 of every 100 adults with an associate's degree (16.6%).

- More than 7 of every 100 adults with an undergraduate college degree (7.4%).

- More than 3 of every 100 adults with a graduate degree (3.6%).

Socio-economic status

- About 26 of every 100 adults who live below the poverty level (26.1%).

- Nearly 14 of every 100 adults who live at or above the poverty level (13.9%).

Geographical Area

- Nearly 19 of every 100 adults who live in the Midwest (18.7%).

- More than 15 of every 100 adults who live in the South (15.3%).

- More than 13 of every 100 adults who live in the Northeast (13.5%).

- More than 12 of every 100 adults who live in the West (12.4%).

Disability

- More than 21 of every 100 adults who reported having a disability/limitation (21.5%)

- Nearly 14 of every 100 adults who reported having no disability/limitation (13.8%)

Sexual Orientation

- More than 20 of every 100 lesbian/gay/bisexual adults (20.6%)

- Nearly 15 of every 100 straight adults (14.9%)

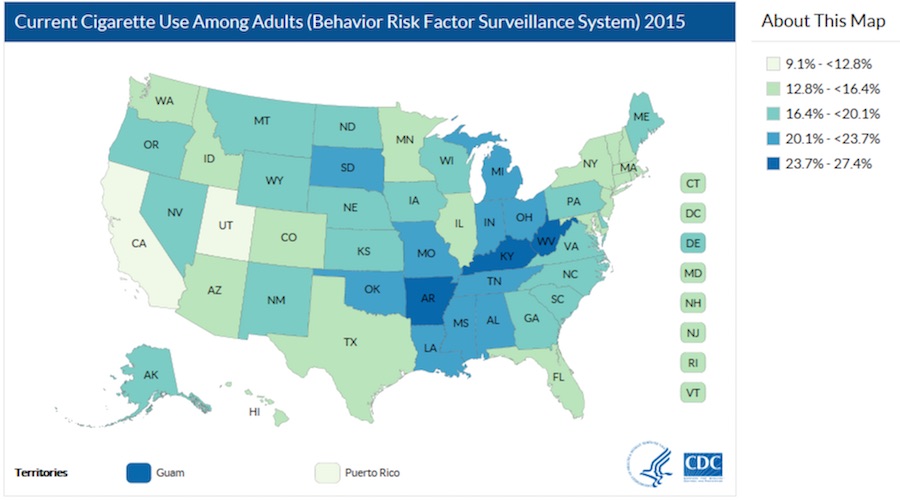

Adult Smokers Distribution

The distribution of smokers in the US can be depicted by this picture.[2]

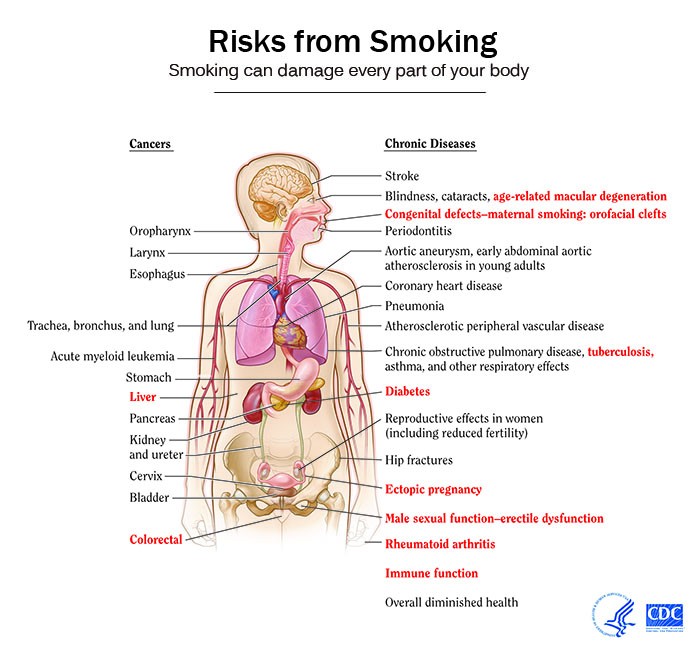

Smoking and Health

The impact of smoking on the health can be summarized as follows:[3][4][5]

Death due to Smoking

- Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States.

- It causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States. This is nearly one in five deaths.

- Cigarette smoking increases risk for death from all causes in men and women.

- The risk of dying from cigarette smoking has increased over the last 50 years in the U.S.

- 80% of all the deaths as a result of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are due to smoking.

Other Health Risks

Smoking has shown to increases the risk of:

- Coronary heart disease by 2 to 4 times

- Stroke by 2 to 4 times

- Men developing lung cancer by 25 times

- Women developing lung cancer by 25.7 times

Smoking causes diminished overall health, increased absenteeism from work, and increased health care utilization and cost

Smoking and Cardiovascular Disease

- Smoking causes stroke and coronary heart disease, which are among the leading causes of death in the United States.

- Even people who smoke fewer than five cigarettes a day can have early signs of cardiovascular disease.

- Smoking damages blood vessels and can make them thicker and grow narrower.

- A stroke may result when:

- A clot blocks the blood flow to part of your brain

- A blood vessel in or around your brain bursts

- Blockages caused by smoking can also diminish the blood flow to the legs and the skin.

Smoking and Respiratory Disease

Smoking can cause lung disease by damaging your airways and the small air sacs (alveoli) found in your lungs.

- Lung diseases caused by smoking include COPD, which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

- Cigarette smoking causes most cases of lung cancer.

- If you have asthma, tobacco smoke can trigger an attack or make an attack worse.

- Smokers are 12 to 13 times more likely to die from COPD than nonsmokers.

Smoking and Cancer

Smoking can cause cancer almost anywhere in your body:

- Bladder

- Blood (acute myeloid leukemia)

- Cervix

- Colon and rectum (colorectal)

- Esophagus

- Kidney and ureter

- Larynx

- Liver

- Oropharynx (includes parts of the throat, tongue, soft palate, and the tonsils)

- Pancreas

- Stomach

- Trachea, bronchus, and lung

- Smoking also increases the risk of dying from cancer and other diseases in cancer patients and survivors.

- If nobody smoked, one of every three cancer deaths in the United States would not occur.

Other Health Risks due to Smoking

Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body and affects a person’s overall health.Smoking can make it harder for a woman to become pregnant. It can also affect her baby’s health before and after birth. Smoking increases risks for:

- Preterm (early) delivery

- Stillbirth (death of the baby before birth)

- Low birth weight

- Sudden infant death syndrome (known as SIDS or crib death)

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Orofacial clefts in infants

- Smoking can also affect men’s sperm, which can reduce fertility and also increase risks for birth defects and miscarriage.

- Smoking can affect bone health.

- Women past childbearing years who smoke have weaker bones than women who never smoked. They are also at greater risk for broken bones.

- Smoking affects the health of your teeth and gums and can cause tooth loss.

- Smoking can increase your risk for cataracts (clouding of the eye’s lens that makes it hard for you to see). It can also cause age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is damage to a small spot near the center of the retina, the part of the eye needed for central vision.

- Smoking is a cause of type 2 diabetes mellitus and can make it harder to control. The risk of developing diabetes is 30–40% higher for active smokers than nonsmokers.

- Smoking causes general adverse effects on the body, including inflammation and decreased immune function.

- Smoking is a cause of rheumatoid arthritis.

Effect of Smoking Cessation on various Risks

- Quitting smoking cuts cardiovascular risks. Just 1 year after quitting smoking, your risk for a heart attack drops sharply.

- Within 2 to 5 years after quitting smoking, your risk for stroke may reduce to about that of a nonsmoker’s.

- If you quit smoking, your risks for cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, and bladder drop by half within 5 years.

- Ten years after you quit smoking, your risk for lung cancer drops by half.

Smoking cessation

General Principles

The 5As are an evidence-based framework for structuring smoking cessation in health care settings. The 5As include: Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange follow-up.

|

Pharmacological

First-line pharmacotherapy includes the multiple forms of nicotine replacement therapy (patch, nasal spray, losenge, gum, inhaler), sustained- release bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline. Second line therapy includes clonidine and nortriptyline and have been found to be efficacious.[6]

The following is a description of the various treatment modalities available:[7]

- Sustained release bupropion hydrochloride:

- Nicotine gum:

- Dose: 1–24 cigarettes/day: 2mg gum (up to 24 pieces/day). ≥ 25 cigarettes/day: 4 mg gum (up to 24 pieces/day).

- Duration: Up to 12 weeks

- Adverse effects: Mouth soreness and dyspepsia

- Nicotine inhaler:

- Dose: 6–16 cartridges/day

- Duration: Up to 6 months

- Adverse effects: Local irritation of mouth and throat

- Nicotine lozenges:

- Nicotine nasal spray:

- Dose: 8–40 doses/day

- Duration: 3–6 months

- Adverse effects: Nasal irritation

- Varenicline:

- Dose: 0.5 mg/day for 3 days followed by 0.5 mg twice/day for 4 days. Then, 1 mg twice/day

- Duration: 3–6 months

- Adverse effects: Nausea, trouble sleeping, vivid/strange dreams and depressed mood

Modalities

Techniques which can increase smokers' chances of successfully quitting are:

- Quitting "cold turkey": abrupt cessation of all nicotine use as opposed to tapering or gradual stepped-down nicotine weaning. It is the quitting method used by 80[8] to 90%[9] of all long-term successful quitters.

- Smoking-cessation support and counseling is often offered over the internet, over the phone quitlines (e.g. 1-800-QUIT-NOW), or in person. One effective way to assist smokers who want to quit is through a telephone quitline which is easily available to all. Professionally run quitlines may help less dependent smokers, but those people who are more heavily dependent on nicotine should seek local smoking cessation services, where they exist, or assistance from a knowledgeable health professional, where they do not. Some evidence suggests that better results are achieved when counseling support and medication are used simultaneously. Quitting with a group of other people who want to quit is also a proven method of getting support, available through many organizations.

- Nicotine replacement therapy, NRT: pharmacological aids that are clinically proven to help with withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and urges (for example, transdermal nicotine patches, gum, lozenges, sprays, and inhalers)

- The antidepressant bupropion, marketed under the brand name Zyban®, helps with withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and urges.

Bupropion is contraindicated in epilepsy, seizure disorder; anorexia/bulimia (eating disorders), patients use of psychosis drugs (MAO inhibitors) within 14 days, patients undergoing abrupt discontinuation of ethanol or sedatives (including benzodiazepines such as Valium)[10]

- Nicotinic receptor antagonist varenicline (Chantix®) (Champix® in the UK)

- Recently, a shot given multiple times over the course of several months, which primes the immune to produce antibodies which attach to nicotine and prevent it from reaching the brain, has shown promise in helping smokers quit. However, this approach is still in the experimental stages. [5]

Alternative techniques

Some 'alternative' techniques which have been used for smoking cessation are:

- Hypnosis clinical trials studying hypnosis as a method for smoking cessation have been inconclusive. (The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3.)

- Herbal preparations such as Kava and Chamomile

- Acupuncture clinical trials have shown that acupuncture's effect on smoking cessation is equal to that of sham/placebo acupuncture. (See Cochrane Review)

- Attending a self-help group such as Nicotine Anonymous[6] and electronic self-help groups such as Stomp It Out[7]

- Laser therapy based on acupuncture principles but without the needles.

- Quit meters: Small computer programs that keep track of quit statistics such as amount of "quit-time", cigarettes not smoked, and money saved.

- Self-help books (Allen Carr, FreshStartMethod etc.) Some of these claim very high success rates but little externally verified evidence of this success exists.

- Spirituality Spiritual beliefs and practices may help smokers quit.[8]

- Smokeless tobacco: Snus is widely used in Sweden, and although it is much healthier than smoking, something which is reflected in the low cancer rates for Swedish men, there are still some concerns about its health impact. [9]

- Herbal and aromatherapy "natural" program formulations.

- Smoking reduction utensil (minitoke)[11]

- Smoking herb substitutions (non-tobacco)[[10]]

Information for healthcare professionals

Clinical practice guidelines by the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) in 2009 stated[12]:

- “The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products.” (Grade A recommendation)

The USPSTF has provided good evidence that demonstrates a clear benefit in both successful smoking cessation and greater than 1 year abstinence when clinicians provide smoking cessation interventions to adult patients. These interventions include behavioral counseling (<10 minutes) and pharmacotherapy. Brief smoking cessation counseling (3 minutes) though less effective, was found to increase quit rates.

A systematic review by the Cochrane Collaboration defined brief advice from a single verbal “stop smoking” statement to counseling up to 20 minutes and cited evidence that demonstrated when “assuming an unassisted quit rate of 2 to 3%, a brief advice intervention can increase quitting by a further 1 to 3%.[13]

Regarding individual studies, several have found that smoking cessation advice is not always given in primary care in patients aged 65 and older[14][15], despite the significant health benefits which can ensue in the older population[16].

Health professionals may follow the "five As" with every smoking patient they come in contact with:[17]

- Ask about smoking

- Advise quitting

- Assess current willingness to quit

- Assist in the quit attempt

- Arrange timely follow-up

See also

- Nicotine Anonymous

- Health promotion

- NicVAX

- Nicotine replacement therapy

- Tobacco cessation clinic

- Tobacco and health

Notes

- ↑ "CDC - Fact Sheet - Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States - Smoking & Tobacco Use".

- ↑ "Map of Cigarette Use Among Adults | STATE System | CDC".

- ↑ "CDC - 2010 Surgeon General's Report - Consumer Booklet - Smoking & Tobacco Use".

- ↑ "QuickStats: Number of Deaths from 10 Leading Causes — National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2010".

- ↑ "CDC - 2014 Surgeon General's Report - Smoking & Tobacco Use".

- ↑ "www.vapremier.com" (PDF).

- ↑ Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff (2008). "A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report". Am J Prev Med. 35 (2): 158–76. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. PMC 4465757. PMID 18617085.

- ↑ Doran CM, Valenti L, Robinson M, Britt H, Mattick RP. Smoking status of Australian general practice patients and their attempts to quit. Addict Behav. 2006 May;31(5):758-66. PMID 16137834

- ↑ American Cancer Society. "Cancer Facts & Figures 2003" (PDF).

- ↑ Charles F. Lacy et al, LEXI-COMP'S Drug Information Handbook 12th edition. Ohio, USA,2004

- ↑ ""Smoking reduction may lead to unexpected quitting"". Retrieved 2007-12-27. Unknown parameter

|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2009). "Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement". Ann Intern Med. 150 (8): 551–5. PMID 19380855.

- ↑ Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T (2013). "Physician advice for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5: CD000165. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4. PMID 23728631.

- ↑ Maguire CP, Ryan J, Kelly A, O'Neill D, Coakley D, Walsh JB. Do patient age and medical condition influence medical advice to stop smoking? Age Ageing. 2000 May;29(3):264-6. PMID 10855911

- ↑ Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S, Utman C, Burton K, Spada J, Guido J. Smokers ages 50+: who gets physician advice to quit? Prev Med. 2000 Oct;31(4):364-9. PMID 11006061

- ↑ Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes. Addiction. 2005 Apr;100 Suppl 2:59-69. PMID 15755262

- ↑ Le Foll B, George TP (2007). "Treatment of tobacco dependence: integrating recent progress into practice". CMAJ. 177 (11): 1373–80. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070627. PMID 18025429.

References

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. Bmj 2004;328(7455):1519.

- Helgason AR, Tomson T, Lund KE, Galanti R, Ahnve S, Gilljam H. Factors related to abstinence in a telephone helpline for smoking cessation. European J Public Health 2004: 14;306-310.

- Henningfield J, Fant R, Buchhalter A, Stitzer M. "Pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence". CA Cancer J Clin. 55 (5): 281–99, quiz 322-3, 325. PMID 16166074. Full text

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99(1):29-38.

- Hutter H.P. et al. Smoking Cessation at the Workplace:1 year success of short seminars. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health. 2006;79:42-48.

- Marks, D.F. The QUIT FOR LIFE Programme:An Easier Way To Quit Smoking and Not Start Again. Leicester: British Psychological Society. 1993.

- Marks, D.F. & Sykes, C. M. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for smokers living in a deprived area of London: outcome at one-year follow-up

Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2005;7:17-24.

- Marks, D.F. Overcoming Your Smoking Habit. London: Robinson.2005.

- Peters MJ, Morgan LC. The pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med J Aust 2002;176:486-490. Fulltext. PMID 12065013.

- Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3):CD000146.

- USDHHS. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research Quality; 2000.

- West R. Tobacco control: present and future. Br Med Bull 2006;77-78:123-36.

- Williamson, DF, Madans, J, Anda, RF, Kleinman, JC, Giovino, GA, Byers, T Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort N Engl J Med 1991 324: 739-745

- World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative

- Zhu S-H, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidene of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline$for smokers. N Engl J Med 2002;347(14):1087-93.

External links

- Helpguide.org - How to Quit Smoking

- Quit Smoking Video

- American Cancer Society Quit Tobacco Resources

- National Cancer Institution Online guide to quitting

- WhyQuit.com

- University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention

- Columbia University School of Nursing Smoking Cessation Portal

- Technique to Quit Smoking

- Stop-tabac.ch: smoking cessation website in 5 languages

- SmokeFreeMe is an online guide to quit smoking