Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Robot: Changing Category:Disease state to Category:Disease) |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

{{SIB}} | {{SIB}} | ||

[[de:Idiopathische interstitielle Pneumonie#Idiopathische_pulmonale_Fibrose_.28IPF.29]] | [[de:Idiopathische interstitielle Pneumonie#Idiopathische_pulmonale_Fibrose_.28IPF.29]] | ||

[[es:Fibrosis pulmonar idiopática]] | [[es:Fibrosis pulmonar idiopática]] | ||

| Line 116: | Line 111: | ||

{{WikiDoc Help Menu}} | {{WikiDoc Help Menu}} | ||

{{WikiDoc Sources}} | {{WikiDoc Sources}} | ||

[[Category:Pulmonology]] | |||

[[Category:Mature chapter]] | |||

[[Category:Disease]] | |||

Revision as of 20:45, 9 December 2011

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | |

| |

|---|---|

| Extensive lung fibrosis from usual interstitial pneumonitis | |

| ICD-9 | 516.3 |

| OMIM | 178500 |

| DiseasesDB | 4815 |

| MedlinePlus | 000069 |

| MeSH | D011658 |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), also known as Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis, is a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology. It is one of the two classic interstitial lung diseases, the other being sarcoidosis.[1]

More specifically, IPF is defined as a distinctive type of chronic fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause associated with a histological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).[2]

Etiology

Pulmonary fibrosis has often been called an autoimmune disease. However, it is perhaps better characterized as an abnormal and excessive deposition of fibrotic tissue in the pulmonary interstitium with minimal associated inflammation.[3] Autoantibodies, a hallmark of autoimmune diseases, are found in a minority of patients with truly idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Moreover, many autoimmune diseases associated with "pulmonary fibrosis", such as scleroderma, are more frequently associated with a related but more inflammatory disease, nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis.[4] It is associated with smoking[5] and exhibits some dependency on the amount of smoking.[6]

Classification

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a type of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), which in turn is a type (or group) of interstitial lung diseases.[7]

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias include:

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (the most common)

- nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

- acute interstitial pneumonia

- respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease

- desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- lymphoid interstitial pneumonia

Clinical features

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis is slightly more common in males and usually presents in patients greater than 50 years of age. Average survival from time of diagnosis varies between 2.5 and 3.5 years, depending on severity, although some patients live greater than 10 years.[7]

Symptoms are gradual in onset. The most common are dyspnea (difficulty breathing), but also include nonproductive cough, clubbing (a disfigurement of the fingers), and crackles (crackling sound in lungs during inhalation).[7] It should be noted that these features are non-specific and can occur in a spectrum of other pulmonary disorders.

The key issue facing clinicians is whether the presenting history, symptoms/signs, radiology, and pulmonary function testing are collectively in keeping with the diagnosis of IPF (which carries the relatively poor prognosis described above) or whether the findings are due to another process. It has long been recognized that patients with interstitial lung disease related to asbestos exposure, drugs (particularly chemotherapeutic agents), a connective tissue disease, or other diseases may have features that are difficult to distinguish from IPF. Important differential diagnostic considerations include asbestosis; interstitial lung disease related to scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease, or rheumatoid arthritis; advanced sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis; chronic pulmonary aspiration; radiation-induced fibrosis; as well as previous therapy with cyclophosphamide, nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, and other drugs.

When diagnostic uncertainty remains, a surgical lung biopsy may be required to establish the diagnosis. Generally, lung biopsy is only undertaken when it is deemed that its risks are outweighed by the potential benefits of identifying a disease process that may be amenable to a treatment that the patient would likely be able to tolerate.

The 2002 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Consensus Guidelines on the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias have formalized criteria for situations in which it is possible to establish the diagnosis of IPF without a lung biopsy.[7]

Radiology

Plain chest x-rays reveal decreased lung volumes, typically with prominent reticular interstitial markings near the lung bases and posteriorly. Honeycombing, a pattern of dense fibrosis characterized by multiple tiny air-filled spaces located at the bases of the lungs, is frequently seen in advanced cases. In less severe cases, these changes may not be evident on a plain chest film.

High-resolution CT scans of the chest demonstrate a symmetrical pattern of bibasilar, peripheral, and subpleural intralobular septal thickening, fibrotic changes, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis. There may be associated ground glass opacity of the lungs but these changes are relatively minor in comparison with the fibrotic changes.[8]

Pulmonary function tests

Spirometry classically reveals a reduction in the vital capacity with either a proportionate reduction in airflows, or increased airflows for the observed vital capacity. The latter finding reflects the increased lung stiffness (reduced lung compliance) associated with pulmonary fibrosis, which leads to increased lung elastic recoil.[9]

Measurement of static lung volumes using body plethysmography or other techniques typically reveals reduced lung volumes (restriction). This reflects the difficulty encountered in inflating the fibrotic lungs.

The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is invariably reduced in IPF and may be the only abnormality in mild or early disease. Its impairment underlies the propensity of patients with IPF to exhibit oxygen desaturation with exercise.

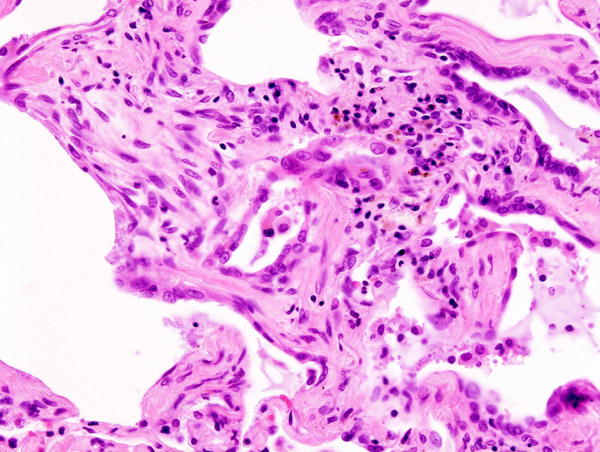

Histology

Histologic specimens for the diagnosis of IPF must be large enough that the pathologist can comment on the underlying lung architecture.

Small biopsies, such as those obtained via transbronchial lung biopsy (performed during bronchoscopy) are generally not sufficient for this purpose. Hence, larger biopsies obtained surgically via a thoracotomy or thoracoscopy are usually necessary.[7]

The histological pattern of fibrosis associated with IPF is referred to as usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).

Although UIP is required for the diagnosis of IPF, it can be seen in other diseases as well.[10]

Key features of UIP include fibroblast foci, a pattern of temporal heterogeneity, dense interstitial fibrosis in a paraseptal and subpleural distribution, and a relatively mild or minor component of interstitial chronic inflammation.[7] To help narrow the differential diagnosis, an absence of significant granulomatous inflammation, microorganisms, eosinophils, and asbestos bodies is required.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IPF can be made by demonstrating UIP pattern on lung biopsy in a patient without clinical features suggesting an alternate diagnosis (see clinical features, above). Establishing the diagnosis of IPF without a lung biopsy has been shown to be reliable when expert clinicians and radiologists concur that the presenting features are typical of IPF.[11] Based on this evidence, the 2002 ATS/ERS Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement on the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias proposes the following criteria for establishing the diagnosis of IPF without a lung biopsy:[7]

Major criteria (all 4 required):

- Exclusion of other known causes of interstitial lung disease (drugs, exposures, connective tissue diseases)

- Abnormal pulmonary function tests with evidence of restriction (reduced vital capacity) and impaired gas exchange (pO2, p(A-a)O2, DLCO)

- Bibasilar reticular abnormalities with minimal ground glass on high-resolution CT scans

- Transbronchial lung biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showing no features to support an alternative diagnosis

Minor criteria (3 of 4 required):

- Age > 50

- Insidious onset of otherwise unexplained exertional dyspnea

- Duration of illness > 3 months

- Bibasilar inspiratory crackles

Treatment

There is currently no consensus on the treatment of IPF. Hence, none of what follows should be taken as specific advice regarding therapy, as the latter is a decision that must be made on a case-by-case basis in individual patients.[12]

There is a lack of large, randomized placebo-controlled trials of therapy for IPF. Moreover, many of the earlier studies were based on the hypothesis that IPF is an inflammatory disorder, and hence studied anti-inflammatory agents such as corticosteroids. Another problem has been that studies conducted prior to the more recent classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias failed to distinguish IPF/UIP from NSIP in particular. Hence, many patients with arguably more steroid-responsive diseases were included in earlier studies, confounding the interpretation of their results.[3]

Small early studies demonstrated that the combination of prednisone with either cyclophosphamide or azathioprine over many months had very modest, if any, beneficial effect in IPF, and were associated with substantial adverse effects (predominantly myelotoxicity). Other treatments studied have included interferon gamma-1b and the antifibrotic agent pirfenidone. While neither drug has been shown to have substantial benefits over time, both are currently being studied in patients with IPF. Finally, the addition of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine to prednisone and azathioprine produced a slight benefit in terms of FVC and DLCO over 12 months of follow up. However, the major benefit appeared to be prevention of the myelotoxicity associated with azathioprine.[13]

References

- ↑ Cooper, Daniel H. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics (32nd edition ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 276. ISBN 978-0781781251. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ "Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Diagnosis and Treatment". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 161 (2): 646–664. 2000. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Selman, Moisés (2001). "Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (2): 136–51. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ King, Jr., Talmadge E. (2005). "Centennial review: clinical advances in the diagnosis and therapy of the interstitial lung diseases". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 172 (3): 268–79.

- ↑ Nagai, Sonoko (2000). "Smoking-related interstitial lung diseases". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 6 (5): 415–9. PMID 10958232. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Baumgartner, KB (1997). "Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 155 (1): 242–248. PMID 9001319. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 "American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 165 (2): 277–304. 2002. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Webb, W. Richard (2001). High-resolution CT of the lung. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 196. ISBN 978-0781722780. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Pellegrino, R. (2005). "Interpretative strategies for lung function tests". European Respiratory Journal. 26 (5): 948–68. Unknown parameter

|publiser=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Kumar, Vinay (2005). Robbins and Cotran's Pathological Basis of Disease (7th ed. ed.). Saunders. p. 729. ISBN 978-0721601878. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Flaherty, Kevin R. (2004). "Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis?". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 170: 904–10. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Walter, N (2006). "Current perspectives on the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. American Thoracic Society. 3 (4): 330–338. PMID 16738197. Retrieved 2008-03-05. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Demedts, Maurits (2005). "High-dose acetylcysteine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The IFIGENIA Study". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (21): 2229–2242. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help)

Template:SIB de:Idiopathische interstitielle Pneumonie#Idiopathische_pulmonale_Fibrose_.28IPF.29 fi:Idiopaattinen keuhkofibroosi