Cholangitis pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

| (36 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{CMG}}; {{AE}} {{FH}} | |||

{{CMG}}; {{AE}} {{ADS}}, {{FH}} | |||

{{Cholangitis}} | {{Cholangitis}} | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

Cholangitis involves two main factors: bacterial | Cholangitis involves two main factors: an increased bacterial presence and elevated intraductal pressure in the [[bile duct]], both of which allow for [[translocation]] of [[bacteria]] or [[endotoxins]] in the [[vascular system]]. Bacterial contamination alone does not usually result in cholangitis. Increased pressure in the [[biliary system]], from obstruction in the bile duct, widens the spaces between the cells lining the duct, which brings bacterially contaminated [[bile]] into the [[bloodstream]]. | ||

== Pathophysiology == | ==Pathophysiology== | ||

The onset of cholangitis involves two factors: increased bacteria in the bile duct | {| align="right" | ||

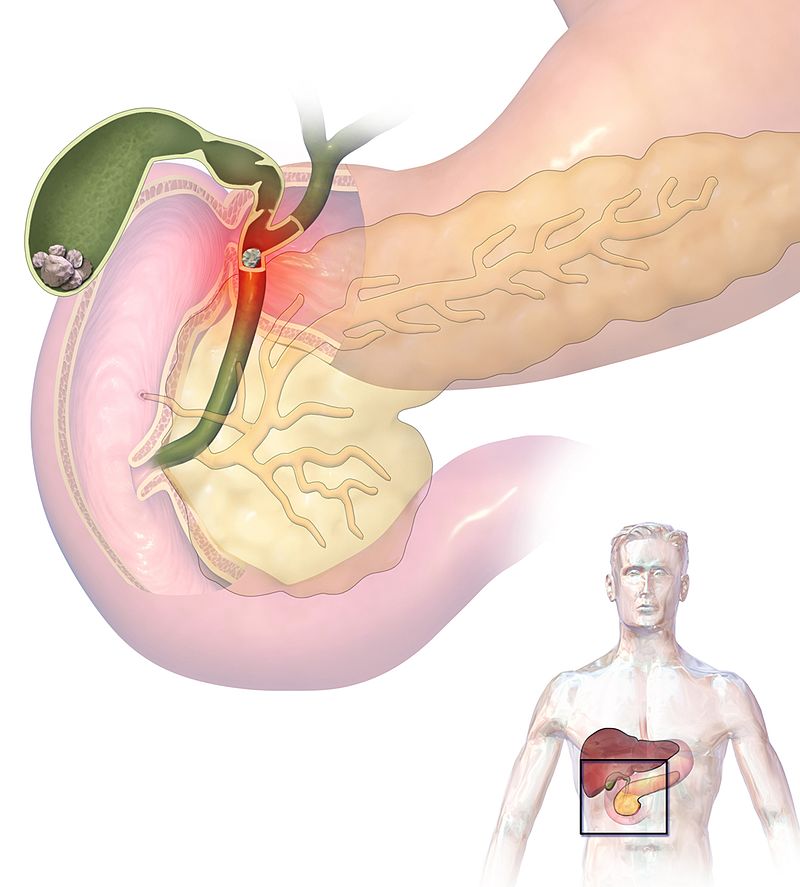

|[[File:Gallstones and Ascending Cholangitis.jpg|thumb|200px|By BruceBlaus Source- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gallstones.png<ref>, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56630024</ref>]] | |||

|} | |||

The onset of cholangitis involves two factors: increased bacteria in the bile duct and elevated intraductal pressure in the bile duct that allows translocation of bacteria or endotoxins into the vascular system. Because of its anatomical characteristics, the [[biliary system]] is likely to be affected by elevated intraductal pressure. With the elevated intraductal biliary pressure, the bile ductules tend to become more permeable to bacteria and toxins. | |||

This can result in serious;even fatal infections, such as hepatic [[abscess|abscesses]] and [[sepsis]].<ref name="pmid17252293">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Wada K, Miura F, Yasuda H, Yamashita Y, Nagino M, Hirota M, Tanaka A, Tsuyuguchi T, Strasberg SM, Gadacz TR |title=Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines |journal=J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=15–26 |year=2007 |pmid=17252293 |pmc=2784509 |doi=10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y |url=}}</ref> Functional changes in sinusoidal lining cells are also common.<ref name="article26">{{cite journal| author=Kawada, N., Takemura, Y., Minamiyama M.| title=Pathophysiology of acute obstructive cholangitis| journal=Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery| year= 1996 | volume= 3 | issue= 1 | pages= 4-8 | pmid=| doi=10.1007/BF01212771 | pmc= | url=http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01212771}} </ref><ref name="pmid17252293">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Wada K, Miura F, Yasuda H, Yamashita Y, Nagino M, Hirota M, Tanaka A, Tsuyuguchi T, Strasberg SM, Gadacz TR |title=Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines |journal=J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=15–26 |date=2007 |pmid=17252293 |pmc=2784509 |doi=10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y |url=}}</ref> | |||

===Pathogenesis=== | ===Pathogenesis=== | ||

Bile, produced by the [[liver]], serves to eliminate cholesterol and [[bilirubin]] from the body, as well as | Bile, which is produced by the [[liver]], serves to eliminate [[cholesterol]] and [[bilirubin]] from the body, as well as to emulsify [[fats]] to make them more soluble in water and aid in their [[digestion]]. It is formed in the liver by [[hepatocytes]] and excreted into the [[common hepatic duct]]. Some bile is stored in the [[gallbladder]] and can be released at time of digestion. All bile reaches the [[duodenum]] through the common bile duct and the [[ampulla of Vater]].<ref name="pmid17556149">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kinney TP |title=Management of ascending cholangitis |journal=Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=289–306, vi |year=2007 |pmid=17556149 |doi=10.1016/j.giec.2007.03.006 |url=}}</ref> | ||

The biliary tree is usually relatively free of bacteria because of certain protective mechanisms: | |||

* The [[sphincter of Oddi]] acts as a mechanical barrier. | |||

* The biliary system normally has low pressure and allows bile to flow freely through. This flushes bacteria, if present, into the [[duodenum]], and does not allow for the establishment of an infection.<ref name="pmid17556149">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kinney TP |title=Management of ascending cholangitis |journal=Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=289–306, vi |year=2007 |pmid=17556149 |doi=10.1016/j.giec.2007.03.006 |url=}}</ref> | |||

Increased pressure within the biliary system resulting from obstruction in the bile duct widens spaces between the cells lining the duct, bringing bacterially contaminated bile in contact with the bloodstream. Increased biliary pressure decreases production of [[immunoglobulins]] (e.g., IgA) in the bile. This results in [[bacteremia]] and gives rise to the [[systemic inflammatory response syndrome]] ([[SIRS]]), which is comprised of [[fever]] (often with rigors), [[tachycardia]], increased [[respiratory rate]], and increased [[white blood cell]] count.<ref name="pmid1563308">{{cite journal |vauthors=Sung JY, Costerton JW, Shaffer EA |title=Defense system in the biliary tract against bacterial infection |journal=Dig. Dis. Sci. |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=689–96 |year=1992 |pmid=1563308 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid21372774">{{cite journal |vauthors=Navaneethan U, Jayanthi V, Mohan P |title=Pathogenesis of cholangitis in obstructive jaundice-revisited |journal=Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol |volume=57 |issue=1 |pages=97–104 |year=2011 |pmid=21372774 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid17252293">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Wada K, Miura F, Yasuda H, Yamashita Y, Nagino M, Hirota M, Tanaka A, Tsuyuguchi T, Strasberg SM, Gadacz TR |title=Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines |journal=J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=15–26 |year=2007 |pmid=17252293 |pmc=2784509 |doi=10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y |url=}}</ref> | |||

Bacterial contamination alone, in absence of obstruction, does not usually result in cholangitis. | |||

==Gross Pathology== | |||

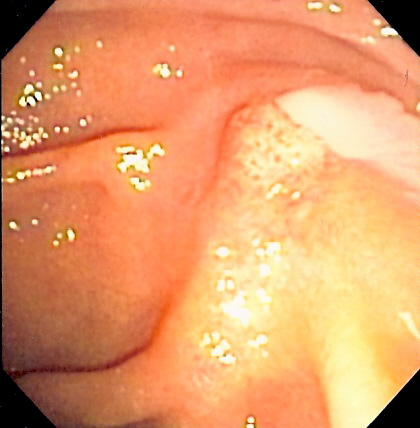

[[File:Cholangitis.jpg|center|thumb|200px|Duodenoscopy image of ampulla of Vater with pus extruding from it, indicative of cholangitis.<ref>https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ascending_cholangitis#/media/File:Cholangitis.jpg</ref>]] | |||

*On gross pathology following are characteristic findings of cholangitis<ref>{{cite book | last = Fyfe | first = Billie | title = Diagnostic pathology | publisher = Amirsys/Elsevier | location = Philadelphia, PA | year = 2016 | isbn = 978-0323376761 }}</ref>: | |||

**Thickening of bile ducts | |||

**Bile stasis ([[cholestasis]]) as shown by greenish discoloration of parenchyma | |||

**Abscesses or pus in bile duct, as seen in the picture (seen more commonly in acute suppurative cholangits) | |||

**Erosions or ulcers in the bile duct | |||

==Microscopic Pathology== | |||

On microscopic histopathological analysis, following features are characteristic findings of acute cholangitis<ref>{{cite book | last = Fyfe | first = Billie | title = Diagnostic pathology | publisher = Amirsys/Elsevier | location = Philadelphia, PA | year = 2016 | isbn = 978-0323376761 }}</ref>: | |||

*[[Cholestasis]] of [[bile canaliculi]] and/or ducts with or without [[Neutrophil|neutrophils]] | |||

*Presence of [[neutrophils]] in the ductular walls and lumina. | |||

* Acute cholangitis in a patient with multiple bile duct procedures. After the biopsy, removal of bile duct stones released pus.<ref name="urlMedical liver disease - Libre Pathology">{{cite web |url=https://librepathology.org/wiki/Medical_liver_disease#Ascending_Cholangitis_.28Acute_Cholangitis.29 |title=Medical liver disease - Libre Pathology |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

<gallery widths="250px"> | |||

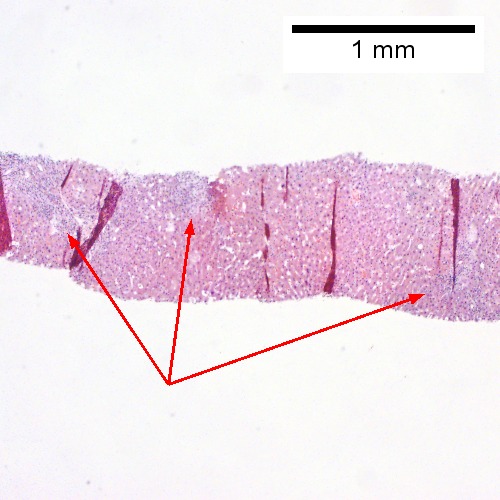

File:Ac chol 1.jpg| A. Rounded, clear (edematous) portal tracts (arrows) separated by hepatocytes with dilated sinusoids | |||

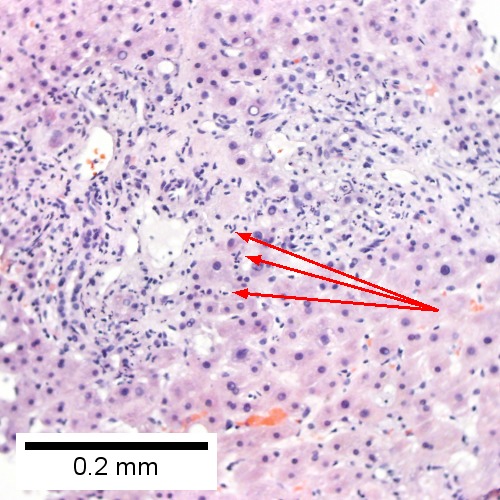

File:Ac chol 2.jpg|B. Neutrophils about hepatocytes (arrows) have spilled into the lobule from a portal tract. | |||

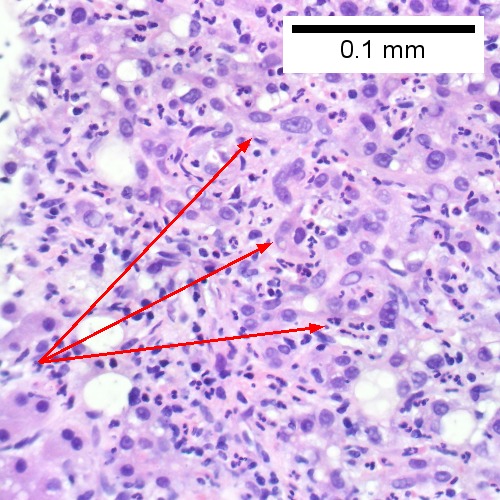

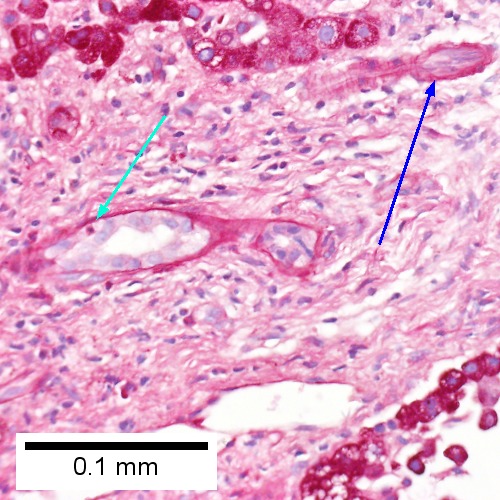

File:Ac chol 3.jpg|C, Proliferated bile ductules (arrows) bearing neutrophils within epithelium and lumens are features of obstruction that should prompt a search for interlobular ducts with acute inflammation | |||

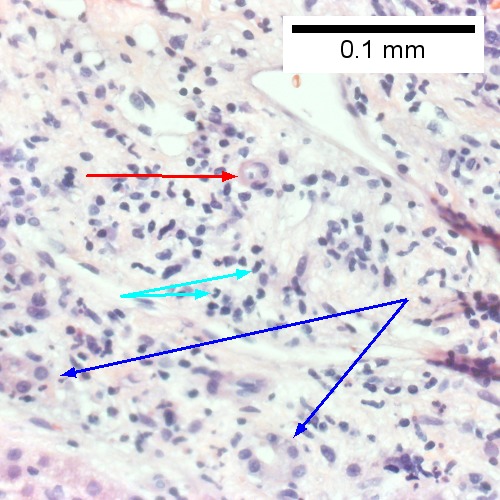

File:Ac chol 4.jpg|D. The epithelium of the ducts can be severely degenerated. Neutrophils (cyan arrows) invade epithelium of an interlobular duct that are recognizable mainly as a circle of rounded nuclei; the associated arteriole (red arrow) should be identified to ensure an interlobular duct is being evaluated. Note the proliferated bile ductules (blue arrows). | |||

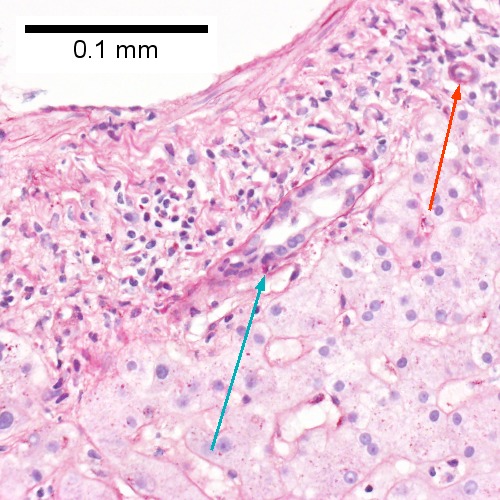

File:Ac chol 5.jpg|E. A PAS without diastase stain colors the arteriole (blue arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow). | |||

File:Ac chol 6.jpg|F. A PAS with diastase stain colors the arteriole (red arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow). | |||

</gallery> | |||

* Patient with sepsis and acute cholangitis.<ref name="urlMedical liver disease - Libre Pathology">{{cite web |url=https://librepathology.org/wiki/Medical_liver_disease#Ascending_Cholangitis_.28Acute_Cholangitis.29 |title=Medical liver disease - Libre Pathology |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

<gallery widths="250px"> | |||

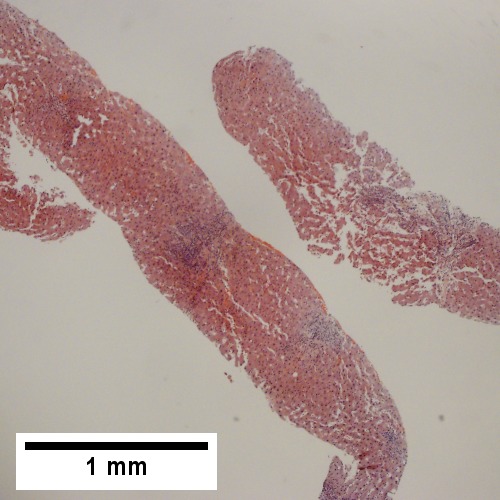

File:Sep chol 1.jpg|A. Low power shows variably sized inflamed portal tracts. | |||

File:Sep chol 2.jpg|B. Trichrome shows dilated sinusoids and space of Disse collagenization. | |||

File:Sep chol 3.jpg|C. Inflammatory focus with macrophages and neutrophils. | |||

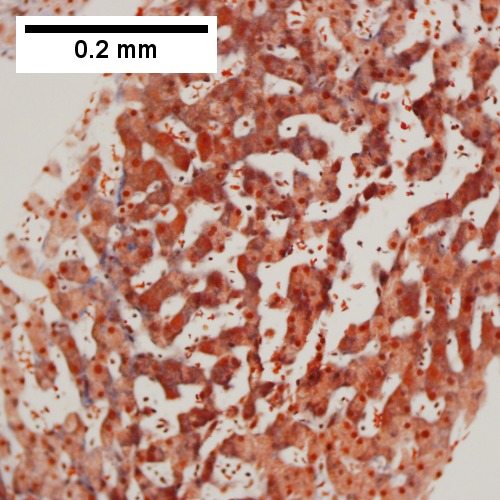

File:Sep chol 4.jpg|D. PAS with diastase shows proliferated bile ductules at edge of triad with neutrophils, which should not be used to make a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis. | |||

File:Sep chol 5.jpg|E. PAS without diastase showing acutely inflamed bile duct, with accompanying blood vessel of similar size, diagnostic of acute cholangitis. | |||

File:Sep chol 6.jpg|F. PAS with diastase showing neutrophil in bille duct lumen, diagnostic of acute cholangitis. | |||

</gallery> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

{{WikiDoc Help Menu}} | |||

{{WikiDoc Sources}} | |||

[[Category:Gastroenterology]] | [[Category:Gastroenterology]] | ||

[[Category:Emergency medicine]] | [[Category:Emergency medicine]] | ||

[[Category:FinalQCRequired]] | |||

[[Category:Disease]] | |||

[[Category:Up-To-Date]] | |||

[[Category:Infectious disease]] | |||

[[Category:Surgery]] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:03, 27 October 2020

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Amandeep Singh M.D.[2], Farwa Haideri [3]

|

Cholangitis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cholangitis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cholangitis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Cholangitis pathophysiology |

Overview

Cholangitis involves two main factors: an increased bacterial presence and elevated intraductal pressure in the bile duct, both of which allow for translocation of bacteria or endotoxins in the vascular system. Bacterial contamination alone does not usually result in cholangitis. Increased pressure in the biliary system, from obstruction in the bile duct, widens the spaces between the cells lining the duct, which brings bacterially contaminated bile into the bloodstream.

Pathophysiology

|

The onset of cholangitis involves two factors: increased bacteria in the bile duct and elevated intraductal pressure in the bile duct that allows translocation of bacteria or endotoxins into the vascular system. Because of its anatomical characteristics, the biliary system is likely to be affected by elevated intraductal pressure. With the elevated intraductal biliary pressure, the bile ductules tend to become more permeable to bacteria and toxins. This can result in serious;even fatal infections, such as hepatic abscesses and sepsis.[2] Functional changes in sinusoidal lining cells are also common.[3][2]

Pathogenesis

Bile, which is produced by the liver, serves to eliminate cholesterol and bilirubin from the body, as well as to emulsify fats to make them more soluble in water and aid in their digestion. It is formed in the liver by hepatocytes and excreted into the common hepatic duct. Some bile is stored in the gallbladder and can be released at time of digestion. All bile reaches the duodenum through the common bile duct and the ampulla of Vater.[4]

The biliary tree is usually relatively free of bacteria because of certain protective mechanisms:

- The sphincter of Oddi acts as a mechanical barrier.

- The biliary system normally has low pressure and allows bile to flow freely through. This flushes bacteria, if present, into the duodenum, and does not allow for the establishment of an infection.[4]

Increased pressure within the biliary system resulting from obstruction in the bile duct widens spaces between the cells lining the duct, bringing bacterially contaminated bile in contact with the bloodstream. Increased biliary pressure decreases production of immunoglobulins (e.g., IgA) in the bile. This results in bacteremia and gives rise to the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which is comprised of fever (often with rigors), tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, and increased white blood cell count.[5][6][2]

Bacterial contamination alone, in absence of obstruction, does not usually result in cholangitis.

Gross Pathology

- On gross pathology following are characteristic findings of cholangitis[8]:

- Thickening of bile ducts

- Bile stasis (cholestasis) as shown by greenish discoloration of parenchyma

- Abscesses or pus in bile duct, as seen in the picture (seen more commonly in acute suppurative cholangits)

- Erosions or ulcers in the bile duct

Microscopic Pathology

On microscopic histopathological analysis, following features are characteristic findings of acute cholangitis[9]:

- Cholestasis of bile canaliculi and/or ducts with or without neutrophils

- Presence of neutrophils in the ductular walls and lumina.

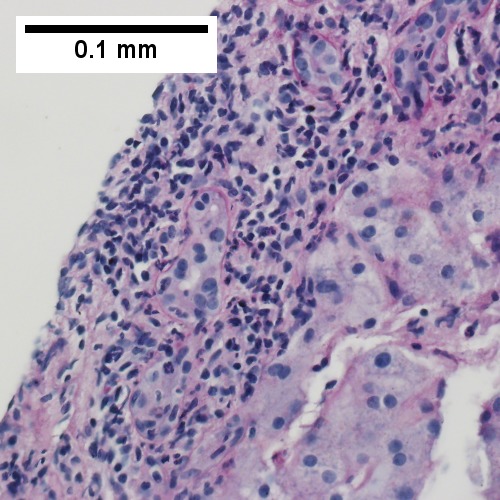

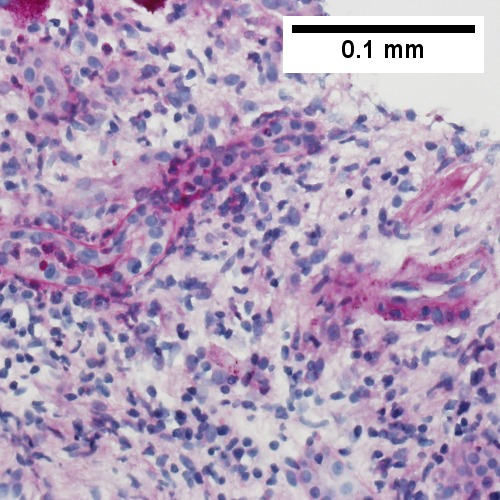

- Acute cholangitis in a patient with multiple bile duct procedures. After the biopsy, removal of bile duct stones released pus.[10]

-

A. Rounded, clear (edematous) portal tracts (arrows) separated by hepatocytes with dilated sinusoids

-

B. Neutrophils about hepatocytes (arrows) have spilled into the lobule from a portal tract.

-

C, Proliferated bile ductules (arrows) bearing neutrophils within epithelium and lumens are features of obstruction that should prompt a search for interlobular ducts with acute inflammation

-

D. The epithelium of the ducts can be severely degenerated. Neutrophils (cyan arrows) invade epithelium of an interlobular duct that are recognizable mainly as a circle of rounded nuclei; the associated arteriole (red arrow) should be identified to ensure an interlobular duct is being evaluated. Note the proliferated bile ductules (blue arrows).

-

E. A PAS without diastase stain colors the arteriole (blue arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow).

-

F. A PAS with diastase stain colors the arteriole (red arrow), as well as the rim of the interlobular duct within which lies a neutrophil (cyan arrow).

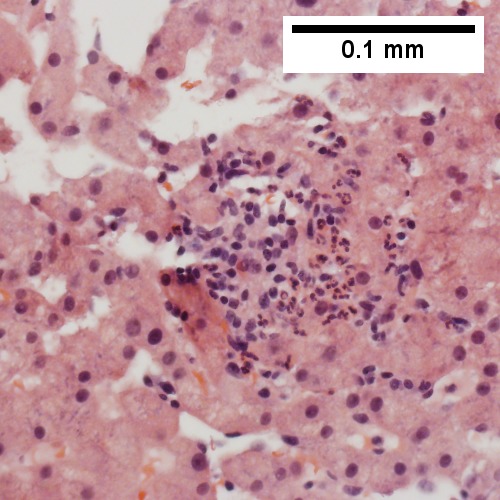

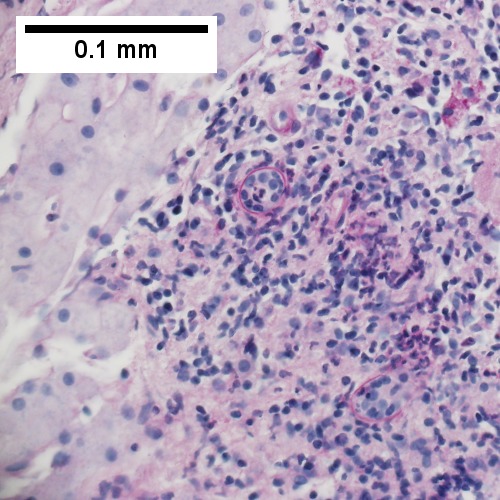

- Patient with sepsis and acute cholangitis.[10]

-

A. Low power shows variably sized inflamed portal tracts.

-

B. Trichrome shows dilated sinusoids and space of Disse collagenization.

-

C. Inflammatory focus with macrophages and neutrophils.

-

D. PAS with diastase shows proliferated bile ductules at edge of triad with neutrophils, which should not be used to make a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis.

-

E. PAS without diastase showing acutely inflamed bile duct, with accompanying blood vessel of similar size, diagnostic of acute cholangitis.

-

F. PAS with diastase showing neutrophil in bille duct lumen, diagnostic of acute cholangitis.

References

- ↑ , CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56630024

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Wada K, Miura F, Yasuda H, Yamashita Y, Nagino M, Hirota M, Tanaka A, Tsuyuguchi T, Strasberg SM, Gadacz TR (2007). "Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 14 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y. PMC 2784509. PMID 17252293.

- ↑ Kawada, N., Takemura, Y., Minamiyama M. (1996). "Pathophysiology of acute obstructive cholangitis". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 3 (1): 4–8. doi:10.1007/BF01212771.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kinney TP (2007). "Management of ascending cholangitis". Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 17 (2): 289–306, vi. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2007.03.006. PMID 17556149.

- ↑ Sung JY, Costerton JW, Shaffer EA (1992). "Defense system in the biliary tract against bacterial infection". Dig. Dis. Sci. 37 (5): 689–96. PMID 1563308.

- ↑ Navaneethan U, Jayanthi V, Mohan P (2011). "Pathogenesis of cholangitis in obstructive jaundice-revisited". Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 57 (1): 97–104. PMID 21372774.

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ascending_cholangitis#/media/File:Cholangitis.jpg

- ↑ Fyfe, Billie (2016). Diagnostic pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Amirsys/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0323376761.

- ↑ Fyfe, Billie (2016). Diagnostic pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Amirsys/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0323376761.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Medical liver disease - Libre Pathology".