Human ehrlichiosis overview

|

Human ehrlichiosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Human ehrlichiosis overview On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Human ehrlichiosis overview |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Human ehrlichiosis overview |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Toward the end of the 19th century, scientists began to understand the important potential for ticks to act as transmitters of disease. In the last decades of the 20th century, several tick-borne diseases have been recognized in the United States, including babesiosis, Lyme disease, and ehrlichiosis.

Ehrlichiosis is caused by several bacterial species in the genus Ehrlichia (pronounced err-lick-ee-uh) which have been recognized since 1935. Over several decades, veterinary pathogens that caused disease in dogs, cattle, sheep, goats, and horses were identified. Currently, three species of Ehrlichia in the United States and one in Japan are known to cause disease in humans; others could be recognized in the future as methods of detection improve.

In 1953, the first ehrlichial pathogen of humans was identified in Japan. Sennetsu fever, caused by Ehrlichia sennetsu, is characterized by fever and swollen lymph nodes. The disease is very rare outside the Far East and Southeast Asia, and most cases have been reported from western Japan.

In the United States, human diseases caused by Ehrlichia species have been recognized since the mid-1980s. The ehrlichioses represent a group of clinically similar, yet epidemiologically and etiologically distinct, diseases caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and a bacterium extremely similar or identical to E. phagocytophila. The remainder of the information on this web page will focus on the types of ehrlichiosis that occur in the United States.

Human ehrlichiosis due to Ehrlichia chaffeensis was first described in 1987. The disease occurs primarily in the southeastern and south central regions of the country and is primarily transmitted by the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) represents the second recognized ehrlichial infection of humans in the United States, and was first described in 1994. The name for the species that causes HGE has not been formally proposed, but this species is closely related or identical to the veterinary pathogens Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila. HGE is transmitted by the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in the United States.

Ehrlichia ewingii is the most recently recognized human pathogen. Disease caused by E. ewingii has been limited to a few patients in Missouri, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, most of whom have had underlying immunosuppression. The full extent of the geographic range of this species, its vectors, and its role in human disease is currently under investigation.

History and Symptoms

The early clinical presentations of ehrlichiosis may resemble nonspecific signs and symptoms of various other infectious and non-infectious diseases. It is unclear if all persons infected with ehrlichiae become ill. It is possible that many infected persons develop an illness so mild they do not seek medical attention or perhaps have no symptoms at all.

Laboratory Findings

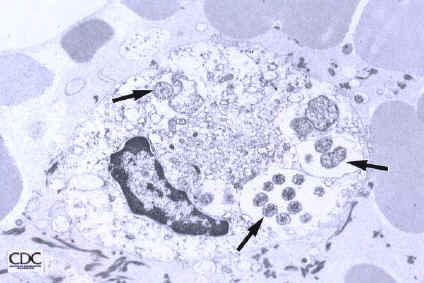

A diagnosis of ehrlichiosis is based on a combination of clinical signs and symptoms and confirmatory laboratory tests. Your doctor can send your blood sample to a reference laboratory for testing. However, the availability of the different types of laboratory tests varies considerably. Other laboratory findings indicative of ehrlichiosis include low white blood cell count, low platelet count, and elevated liver enzymes.

Medical Therapy

Appropriate antibiotic treatment should be initiated immediately when there is a strong suspicion of ehrlichiosis on the basis of clinical and epidemiologic findings. Treatment should not be delayed until laboratory confirmation is obtained. Fever generally subsides within 24-72 hours after treatment with doxycycline or other tetracyclines. In fact, failure to rapidly respond to a tetracycline antibiotic argues against a diagnosis of ehrlichiosis. Preventative therapy in non-ill patients who have had recent tick bites is not warranted.

Prevention

Limiting exposure to ticks reduces the likelihood of ehrlichial infection. In persons exposed to tick-infested habitats, prompt careful inspection and removal of crawling or attached ticks is an important method of preventing disease. It may take several hours of attachment before microorganisms are transmitted from the tick to the host.