Sandbox: Dr.Reddy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

*In the early 1990s, an average of 4 million people got varicella, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized (range, 8,000 to 18,000), and 100 to 150 died each year. In the 1990s, the highest rate of varicella was reported in preschool-aged children. <ref name="urlChickenpox | Monitoring Vaccine Impact | Varicella | CDC">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/surveillance/monitoring-varicella.html |title=Chickenpox | Monitoring Vaccine Impact | Varicella | CDC |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

*Since the chickenpox vaccine was developed in 1995, the major data of chickenpox in the environment is before 1995. In the prevaccine era, varicella was endemic in the United States, and virtually all persons acquired varicella by adulthood. As a result, the number of cases occurring annually was estimated to approximate the birth cohort, or approximately 4 million per year. Varicella was removed from the list of nationally notifiable conditions in 1981, but some states continued to report cases to CDC. The majority of cases (approximately 85%) occurred among children younger than 15 years of age. | |||

*In 2004, varicella vaccination coverage among children 19–35 months in two of the active surveillance areas was estimated to be 89% and 90%. Compared with 1995, varicella cases declined 83%–93% by 2004. Cases declined most among children aged 1–4 and 5–9 years, but a decline occurred in all age groups including infants and adults, indicating reduced transmission of the virus in 308 Varicella 21 these groups. The reduction of varicella cases is the result of the increasing use of varicella vaccine. Varicella vaccine coverage among 19–35-month-old children was estimated by the National Immunization Survey to be 90% in 2007. | |||

*Despite high one-dose vaccination coverage and success of the vaccination program in reducing varicella morbidity and mortality, varicella surveillance indicates that the number of reported varicella cases appears to have plateaued. An increasing proportion of cases represent breakthrough infection (chickenpox occurring in a previously vaccinated person). In 2001–2005, outbreaks were reported in schools with high varicella vaccination coverage (96%–100%). These outbreaks had many similarities: all occurred in elementary schools; vaccine effectiveness was within the expected range (72%–85%); the highest attack rates occurred among the younger students; each outbreak lasted about 2 months; and persons with breakthrough infection transmitted the virus although the breakthrough disease was mild.Overall attack rates among vaccinated children were 11%–17%, with attack rates in some classrooms as high as 40%. These data indicate that even in settings where almost everyone was vaccinated and vaccine performed as expected, varicella outbreaks could not be prevented with the current one-dose vaccination policy. | |||

*These observations led to the '''recommendation in 2006 for a second routine dose''' of varicella vaccine. Chickenpox used to be very common in the United States. In the early 1990s, an average of 4 million people got varicella, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized (range, 8,000 to 18,000), and 100 to 150 died each year. In the 1990s, the highest rate of varicella was reported in preschool-aged children. | |||

*Chickenpox vaccine became available in the United States in 1995. In 2014, 91% of children 19 to 35 months old in the United States had received one dose of varicella vaccine, varying from 83% to 95% by state. Among adolescents 13 to 17 years of age without a prior history of disease, 95% had received 1 dose of varicella vaccine, and 81% had received 2 doses of the vaccine. Eighty-five percent of adolescents had either a history of varicella disease or received 2 doses of varicella vaccine. Each year, more than 3.5 million cases of varicella, 9,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths are prevented by varicella vaccination in the United States. | |||

− | |||

− | |||

*Each year, more than 3.5 million cases of varicella, 9,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths are prevented by varicella vaccination in the United States. | |||

Revision as of 22:10, 28 June 2017

- In the early 1990s, an average of 4 million people got varicella, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized (range, 8,000 to 18,000), and 100 to 150 died each year. In the 1990s, the highest rate of varicella was reported in preschool-aged children. [1]

- Since the chickenpox vaccine was developed in 1995, the major data of chickenpox in the environment is before 1995. In the prevaccine era, varicella was endemic in the United States, and virtually all persons acquired varicella by adulthood. As a result, the number of cases occurring annually was estimated to approximate the birth cohort, or approximately 4 million per year. Varicella was removed from the list of nationally notifiable conditions in 1981, but some states continued to report cases to CDC. The majority of cases (approximately 85%) occurred among children younger than 15 years of age.

- In 2004, varicella vaccination coverage among children 19–35 months in two of the active surveillance areas was estimated to be 89% and 90%. Compared with 1995, varicella cases declined 83%–93% by 2004. Cases declined most among children aged 1–4 and 5–9 years, but a decline occurred in all age groups including infants and adults, indicating reduced transmission of the virus in 308 Varicella 21 these groups. The reduction of varicella cases is the result of the increasing use of varicella vaccine. Varicella vaccine coverage among 19–35-month-old children was estimated by the National Immunization Survey to be 90% in 2007.

- Despite high one-dose vaccination coverage and success of the vaccination program in reducing varicella morbidity and mortality, varicella surveillance indicates that the number of reported varicella cases appears to have plateaued. An increasing proportion of cases represent breakthrough infection (chickenpox occurring in a previously vaccinated person). In 2001–2005, outbreaks were reported in schools with high varicella vaccination coverage (96%–100%). These outbreaks had many similarities: all occurred in elementary schools; vaccine effectiveness was within the expected range (72%–85%); the highest attack rates occurred among the younger students; each outbreak lasted about 2 months; and persons with breakthrough infection transmitted the virus although the breakthrough disease was mild.Overall attack rates among vaccinated children were 11%–17%, with attack rates in some classrooms as high as 40%. These data indicate that even in settings where almost everyone was vaccinated and vaccine performed as expected, varicella outbreaks could not be prevented with the current one-dose vaccination policy.

- These observations led to the recommendation in 2006 for a second routine dose of varicella vaccine. Chickenpox used to be very common in the United States. In the early 1990s, an average of 4 million people got varicella, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized (range, 8,000 to 18,000), and 100 to 150 died each year. In the 1990s, the highest rate of varicella was reported in preschool-aged children.

- Chickenpox vaccine became available in the United States in 1995. In 2014, 91% of children 19 to 35 months old in the United States had received one dose of varicella vaccine, varying from 83% to 95% by state. Among adolescents 13 to 17 years of age without a prior history of disease, 95% had received 1 dose of varicella vaccine, and 81% had received 2 doses of the vaccine. Eighty-five percent of adolescents had either a history of varicella disease or received 2 doses of varicella vaccine. Each year, more than 3.5 million cases of varicella, 9,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths are prevented by varicella vaccination in the United States.

−

−

- Each year, more than 3.5 million cases of varicella, 9,000 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths are prevented by varicella vaccination in the United States.

- In the early 1990s, an average of 4 million people got varicella, 10,500 to 13,000 were hospitalized (range, 8,000 to 18,000), and 100 to 150 died each year. In the 1990s, the highest rate of varicella was reported in preschool-aged children. [1]

Template:Topic Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Overview

Topic

References

| style="background: #DCDCDC; padding: 5px;"|Chickenpox

|

- It commonly starts with conjunctival and catarrhal symptoms and then characteristic spots appearing in two or three waves, mainly on the body and head, rather than the hands, becoming itchy raw pox (small open sores which heal mostly without scarring). Touching the fluid from a chickenpox blister can also spread the disease.

|-

Vaccine is recommended for children as well as adults who haven't been vaccinated previously to prevent chickenpox. Two doses of chickenpox vaccine are recommended for children who never have contracted chickenpox at the following intervals. First dose is recommended between 12-15 months of age. Second dose is recommended around 4-6 years of age and also it may be given earlier if the gap between the doses is at least three months from the first dose. In adults, vaccine is recommended in people who are of 13 years of age or older. There should be a gap of atleast 28 days between the two doses.

gp

The following gross pathological images depict the progression of the disease based on the distribution of rash.

-

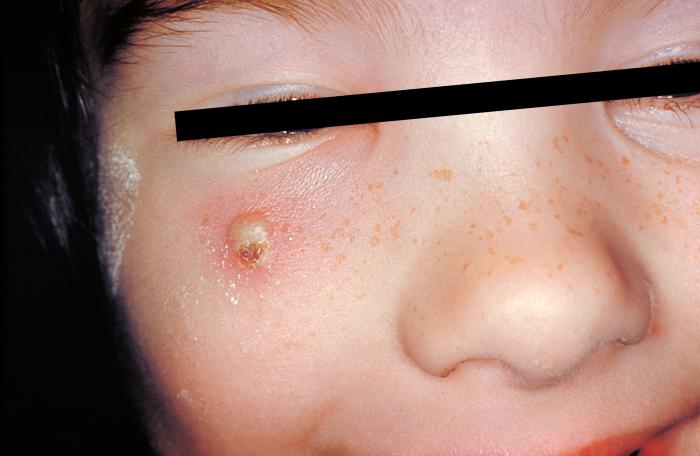

Girl with a secondary skin infection due to chickenpox.

-

Chickenpox in unvaccinated adult.

-

Chickenpox in an unvaccinated adult.

-

Chickenpox in unvaccinated child.

-

Vasculitis leukocytoclasia. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [1]

-

Varicella From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [1]

- Primary varicella is a common childhood disease in Western countries, which presents as pruritic macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusts, usually on the back, chest, face, and abdomen.

- The vesicles progress to pustules, then to crusts that eventually are lost. Scarring and changes in pigmentation can result, but the most frequent sequela of zoster is postherpetic neuralgia, which is usually most severe in the elderly.

- Primary varicella or herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients can sometimes involve internal organs (eg, lungs, liver, brain) resulting in high rates of morbidity and mortality.[2]

- Chickenpox typically requires no medical treatment in otherwise healthy individuals. Only symptomatic treatment is advised to ease the discomfort.

- VZV can be spread by varicella or herpes zoster carrying:

- Patients

- Health care providers

- Visitors

- Individuals susceptible to the be infected by VZV include:

- Patients and health care providers in hospitals

- Long-term-care facilities

- Other healthcare settings

- These transmissions have been attributed to

- Delays in the diagnosis of varicella and zoster

- Delay in the reporting of varicella and zoster

- Failures to promptly implement control measures

Immunocompromised Patients

- Immunocompromised persons who get varicella are at risk of developing visceral dissemination (VZV infection of internal organs) leading to pneumonia, hepatitis, encephalitis, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. They can have an atypical varicella rash with more lesions, and they can be sick longer than immunocompetent persons who get varicella. The lesions may continue to erupt for as long as 10 days, may appear on the palms and soles, and may be hemorrhagic.

People with HIV or AIDS

- Children with HIV infection tend to have atypical rash with new crops of lesions presenting for weeks or months. HIV-infected children may develop chronic infection in which new lesions appear for more than one month. The lesions may initially be typical maculopapular vesicular lesions but can later develop into non-healing ulcers that become necrotic, crusted, and hyperkeratotic. This is more likely to occur in HIV-infected children with low CD4 counts.

- In adults, the disease can be more severe, though the incidence is much less common. Infection in adults is associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to pneumonia, hepatitis and encephalitis. In particular, up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox develop pneumonia, the severity of which increases with onset later in gestation. In England and Wales, 75% of deaths due to chickenpox are in adults. Inflammation of the brain, or encephalitis, can occur in immunocompromised individuals, although the risk is higher with herpes zoster.[3]Necrotizing fasciitis

- Secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions, manifesting as impetigo, cellulitis, and erysipelas, is the most common complication in healthy children. Disseminated primary varicella infection, usually seen in the immunocompromised or adult populations, may have high morbidity. Ninety percent of cases of varicella pneumonia occur in the adult population. Rarer complications of disseminated chickenpox also include myocarditis, hepatitis, and glomerulonephritis.

Primary varicella (chickenpox)

- Primary varicella is a common childhood disease in Western countries, which presents as pruritic macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, and crusts, usually on the back, chest, face, and abdomen.

- In immunocompetent children, chickenpox is generally a mild disease with little morbidity and rare mortality.

- Primary varicella is associated with more morbidity in adults. Following resolution of primary varicella, VZV persists in a latent form in dorsal ganglion cells for what is usually an extended period of time. For reasons that are still poorly understood, VZV can later start replicating in the ganglion, producing severe neuralgia and spread of the virus down the sensory nerve. Vesicles then appear on the skin in the distribution of this nerve, producing the characteristic dermatomal rash of shingles. The vesicles progress to pustules, then to crusts that eventually are lost. Scarring and changes in pigmentation can result, but the most frequent sequela of zoster is postherpetic neuralgia, which is usually most severe in the elderly.

- In immunocompromised patients can sometimes involve internal organs (eg, lungs, liver, brain) resulting in high rates of morbidity and mortality.

- Primary varicella or herpes zoster Congenital VZV infection is uncommon but can result in severe congenital malformations.

- A Tzanck smear can be useful to demonstrate a herpesvirus infection, but confirmation of VZV as the cause of the infection requires at least one of the following tests: culture, serology, direct immunofluorescence staining, or molecular techniques. [2]

Zoster (shingles)

- Anyone who has recovered from chickenpox may develop shingles; even children can get shingles. The risk of shingles increases as one gets older. About 50% all cases occur in men and women 60 years old or older. One in every three people develop shingles in their lifetime which is estimated at 1 million cases every year.

- Certain cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive individuals, and people on immunosuppressive drugs such as steroids and drugs given after organ transplantation have a greater risk of getting shingles.

- Shingles typically occurs only once in a person's lifetime. However, a person can have a second or even a third episode.

- Some studies have found that VZV dissemination to the visceral organs is less common in children with HIV than in other immunocompromised patients with VZV infection. The rate of complications may also be lower in HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy or HIV-infected persons with higher CD4 counts at the time of varicella infection. Retinitis can occur among HIV-infected children and adolescents.

- Most adults, including those who are HIV-positive have already had varicella disease and are VZV seropositive. As a result, varicella is relatively uncommon among HIV-infected adults.

Neonates

- Varicella infection in pregnant women can lead to viral transmission via the placenta and infection of the fetus. If infection occurs during the first 28 weeks of gestation, this can lead to fetal varicella syndrome (also known as congenital varicella syndrome). Effects on the fetus can range in severity from underdeveloped toes and fingers to severe anal and bladder malformation. Possible problems include:

- Damage to brain: encephalitis, microcephaly, hydrocephaly, aplasia of brain

- Damage to the eye (optic stalk, optic cap, and lens vesicles), microphthalmia, cataracts, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy

- Other neurological disorder: damage to cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord, motor/sensory deficits, absent deep tendon reflexes, anisocoria/Horner's syndrome

- Damage to body: hypoplasia of upper/lower extremities, anal and bladder sphincter dysfunction

- Skin disorders: (cicatricial) skin lesions, hypopigmentation

- Infection late in gestation or immediately post-partum is referred to as neonatal varicella. Maternal infection is associated with premature delivery. The risk of the baby developing the disease is greatest following exposure to infection in the period 7 days prior to delivery and up to 7 days post-partum. The neonate may also be exposed to the virus via infectious siblings or other contacts, but this is of less concern if the mother is immune. Newborns who develop symptoms are at a high risk of pneumonia and other serious complications of the disease. [4]

Pregnant Women

- Pregnant women who get varicella are at risk for serious complications; they are at increased risk for developing pneumonia, and in some cases, may die as a result of varicella.

- If a pregnant woman gets varicella in her 1st or early 2nd trimester, her baby has a small risk (0.4 – 2.0 percent) of being born with congenital varicella syndrome. The baby may have scarring on the skin, abnormalities in limbs, brain, and eyes, and low birth weight.

- If a woman develops varicella rash from 5 days before to 2 days after delivery, the newborn will be at risk for neonatal varicella. In the absence of treatment, up to 30% of these newborns may develop severe neonatal varicella infection.

Infants without Passive Immunity

- Children under one year of age whose mothers have had chickenpox are not very likely to catch it. If they do, they often have mild cases because they retain partial immunity from their mothers' blood. Children under one year of age whose mothers have not had chickenpox, or whose inborn immunity has already waned, can get severe chickenpox.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tyring SK (1992). "Natural history of varicella zoster virus". Semin Dermatol. 11 (3): 211–7. PMID 1390036.

- ↑ "Definition of Chickenpox". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- ↑ Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (September 2007). "Chickenpox in Pregnancy" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-12.

![Vasculitis leukocytoclasia. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [1]](/images/4/47/Varicella_10.jpeg)

![Varicella From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [1]](/images/e/e7/Varicella_02.jpeg)