|

|

| (28 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | '''For patient information, click [[Asherman’s syndrome (patient information)|here]]''' |

| | |

| {{Infobox_Disease | | {{Infobox_Disease |

| | Name = Ashermans syndrome | | | Name = {{PAGENAME}} |

| | Image = | | | Image = Hysteroscopy of Asherman's Syndrome.jpg |

| | Caption = | | | Caption = Hysteroscopic view. |

| | DiseasesDB = 946 | | | DiseasesDB = 946 |

| | ICD10 = {{ICD10|N|85|6|n|80}} | | | ICD10 = {{ICD10|N|85|6|n|80}} |

| Line 13: |

Line 15: |

| | MeshID = D006175 | | | MeshID = D006175 |

| }} | | }} |

| {{SI}} | | {{Asherman's syndrome}} |

|

| |

|

| '''Editor-In-Chief:''' Canan S Fornusek, PhD [mailto:csfornusek@gmail.com] | | '''Editor(s)-in-Chief:''' {{CMG}} [[User:Csinfor|Canan S Fornusek, Ph.D.]]; '''Associate Editor-In-Chief:''' {{skhan}} |

|

| |

|

| '''Associate Editor-In-Chief:''' {{MUT}} | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome overview|Overview]]== |

|

| |

|

| {{EH}}

| | ==[[Asherman's syndrome historical perspective|Historical Perspective]]== |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Ultrasound of Asherman's syndrome.jpg|thumb|left|Ultrasound view.]] | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome classification|Classification]]== |

| ''' Asherman's syndrome''' (AS), also called "uterine [[synechia]]e" or intrauterine [[adhesions]] (IUA), presents a condition characterized by the presence of adhesions and/or fibrosis within the uterine cavity due to scars. A number of other terms have been used to describe the condition and related conditions including: [[traumatic intrauterine adhesions]], uterine/[[cervical atresia]], [[traumatic uterine atrophy]], [[sclerotic endometrium]], [[endometrial sclerosis]]. In this article AS and IUA are used interchangeably.

| |

|

| |

|

| == Causes and features == | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome pathophysiology|Pathophysiology]]== |

| [[Image:HSG Ashermans syndrome.jpg|thumb|left|HSG view.]]

| |

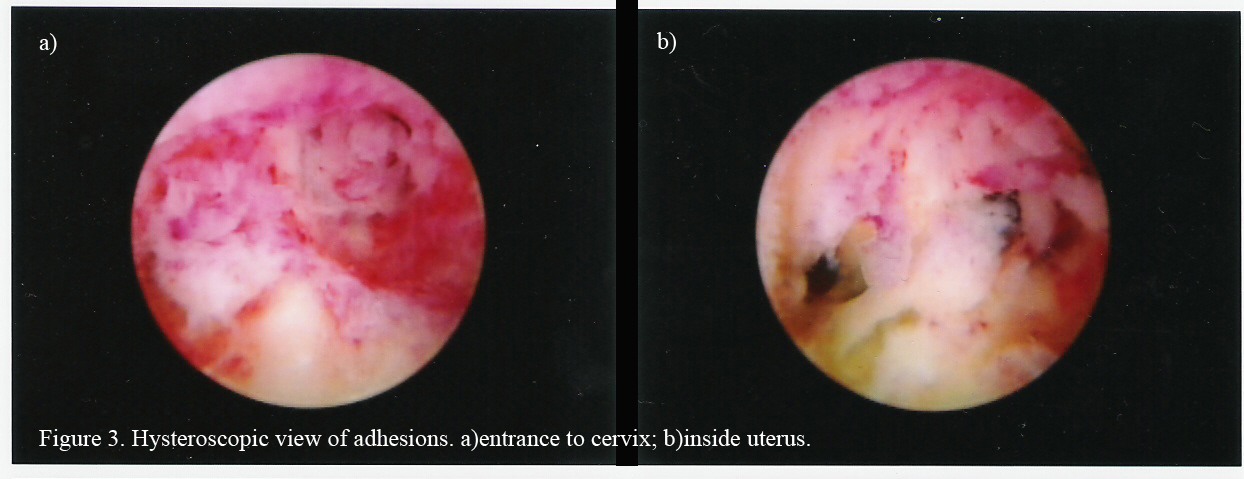

| [[Image:Hysteroscopy of Asherman's Syndrome.jpg|left|thumb|Hysteroscopic view.]] | |

| The cavity of the [[uterus]] is lined by the [[endometrium]]. This lining is composed of two layers, the functional layer which is shed during menstruation and an underlying basal layer which is necessary for regenerating the functional layer. Trauma to the basal layer, typically after a [[dilation and curettage]] (D&C) performed after a [[miscarriage]], or [[childbirth|delivery]], or for elective [[abortion]] can lead to the development of intrauterine scars resulting in adhesions which can obliterate the cavity to varying degrees. In the extreme, the whole cavity has been scarred and occluded. Even with relatively few scars, the endometrium may fail to respond to [[estrogen]]s and rests. Often, patients experience secondary menstrual irregularities characterized by changes in flow and duration of bleeding ([[amenorrhea]], [[hypomenorrhea]], or [[oligomenorrhea]])<ref name="Klein">{{cite journal |author=Klein SM, Garcia C-R |title=Asherman's syndrome: a critique and current review |journal=Fertility and Sterility |volume=24 |issue=9 |pages=722–735. |year=1973 |pmid=4725610 |doi=}}</ref> and become infertile. Menstrual anomlies are often but not always correlated with severity: adhesions restricted to only the [[cervix]] or lower uterus may block menstruation. Pain during menstruation and ovulation are also sometimes experienced, and can be attributed to blockages.

| |

|

| |

|

| Asherman's syndrome occurs most frequently after a D&C is performed on a recently pregnant uterus, following a missed or incomplete miscarriage, birth, or elective termination ([[abortion]]) to remove retained products of conception/placental remains. As the same procedure is used in all three situations, Asherman's can result in all of the above circumstances. It affects women of all races and ages as there is no underlying predisposition or genetic basis to its development. According to a study on 1900 patients with Asherman's syndrome, over 90% of the cases occurred following pregnancy-related curettage.<ref name="Schenker">{{cite journal |author=Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. |title=Intra-uterine adhesions: an updated appraisal |journal=Fertility Sterility |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=593–610. |year=1982 |pmid=6281085

| | ==[[Asherman's syndrome causes|Causes]]== |

| |doi=}}</ref>

| |

| Depending on the degree of severity, Asherman's syndrome may result in infertility, repeated miscarriages, pain from trapped blood, and future obstetric complications<ref name="Valle">{{cite journal |author=Valle RF, and Sciarra JJ |title=Intrauterine adhesions: Hystreoscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment and reproductive outcome |journal=. Am J Obstet |volume=158 |issue=6Pt1 |pages=1459–1470 |year=1988 |pmid=3381869 |doi=}}</ref>(see Prognoses below). There is evidence that left untreated, the obstruction of menstrual flow resulting from scarring can lead to [[endometriosis]].<ref name="Buttram">{{cite journal |author=Buttram VC, Turati, G |title=Uterine synechiae: variations in severity and some conditions which may be conducive to severe adhesions |journal=Int J Fertil |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=98–103 |year=1977 |pmid=20418 |doi=}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| Asherman's can also result from other pelvic surgeries including [[Cesarean sections]],<ref name="Schenker">{{cite journal |author=Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. |title=Intra-uterine adhesions: an updated appraisal |journal=Fertility Sterility |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=593–610. |year=1982 |pmid=6281085

| | ==[[Asherman's syndrome differential diagnosis|Differentiating Asherman's syndrome from other Diseases]]== |

| |doi=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Rochet Y, Dargent D, Bremond A, Priou G, Rudigoz RC |title=The obstetrical outcome of women with surgically treated uterine synechiae (in French) |journal=J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod |volume=8 |issue=8 |pages=723–726. |year=1979 |pmid=553931 |doi=}}</ref> removal of fibroid tumours ([[myomectomy]]) and from other causes such as [[IUDs]], pelvic [[irradiation]], [[schistosomiasis]]<ref> {{cite journal |author=Krolikowski A, Janowski K, Larsen JV. |title=Asherman syndrome caused by schistosomiasis |journal=Obstet Gynecol. |volume=85 |issue=5Pt2 |pages=898–9 |year=1995 |pmid=7724154 |doi=10.1016/0029-7844(94)00371-J}}</ref> and genital [[tuberculosis]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Netter AP, Musset R, Lambert A Salomon Y |title=Traumatic uterine synechiae: a common cause of menstrual insufficiency, sterility, and abortion |journal=Am J Obstet Gynecol. |volume=71 |issue=2 |pages=368–75 |year=1956 |pmid=13283012 |doi=}}</ref> Chronic [[endometritis]] from genital tuberculosis is a significant cause of severe IUA in the developing world, often resulting in total obliteration of the uterine cavity which is difficult to treat.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Bukulmez O, Yarali H, Gurgan T. |title=Total corporal synechiae due to tuberculosis carry a very poor prognosis following hysteroscopic synechialysis |journal=Hum Reprod |volume=14 |issue=8 |pages=1960–1961. |year=1999 |pmid=10438408 |doi=10.1093/humrep/14.8.1960}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| An artificial form of Asherman's syndrome can be surgically induced by [[endometrial ablation]] in women with excessive uterine bleeding, in lieu of [[hysterectomy]].

| | ==[[Asherman's syndrome epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== |

|

| |

|

| ==Incidence== | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome risk factors|Risk Factors]]== |

| It is estimated that up to 5% of D&Cs result in Asherman's. More conservative estimates put this rate at 1%. Asherman's results from 25% of D&Cs performed 1-4 weeks post-partum<ref>Parent B, Barbot J, Dubuisson JB. Uterine synechiae (in French). Encyl Med Chir Gynecol 1988; 140A (Suppl): 10-12.</ref>,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rochet Y, Dargent D, Bremond A, Priou G, Rudigoz RC |title=The obstetrical outcome of women with surgically treated uterine synechiae (in French) |journal=J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod |volume=8 |issue=8 |pages=723–726. |year=1979 |pmid=553931 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="Buttram">{{cite journal |author=Buttram UC, Turati G. |title=Uterine synechiae: variation in severity and some conditions which may be conductive to severe adhesions |journal=Int J Fertil |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=98–103. |year=1977 |pmid=20418 |doi=}}</ref> 30.9% of D&Cs performed for missed miscarriages and 6.4% of D&Cs performed for incomplete miscarriages.<ref name="Adoni">{{cite journal |author=Adoni A, Palti Z, Milwidsky A, Dolberg M. |title=The incidence of intrauterine adhesions following spontaneous abortion |journal=[[Int J Fertil]]. |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=117–118. |year=1982 |pmid=6126446

| |

| |doi=}}</ref> In the case of missed miscarriages, the time period between fetal demise and curettage increases the likelihood of adhesion formation to over 30.9%<ref name="Schenker">{{cite journal |author=Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. |title=Intra-uterine adhesions: an updated appraisal |journal=Fertility Sterility |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=593–610. |year=1982 |pmid=6281085

| |

| |doi=}}</ref><ref>Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G. Septums and synechiae: approaches to surgical correction. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2006; 49:767-788.

| |

| </ref> The risk of Asherman's also increases with the number of procedures: one study estimated the risk to be 16% after one D&C and 32% after 3 or more D&Cs.<ref name="Friedler">{{cite journal |author=Friedler S, Margalioth EJ, Kafka I, Yaffe H. |title=Incidence of postabortion intra-uterine adhesions evaluated by hysteroscopy: a prospective study |journal=Hum Reprod |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=442–444. |year=1993 |pmid=8473464 |unused_data=|doi}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Prevalence in the general population== | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome screening|Screening]]== |

| The true prevalence of Asherman's syndrome is unclear as many doctors are unaware of the symptoms or diagnosis. Increased awareness about the condition and its diagnosis is also expected to reveal a higher frequency than previously reported. The condition was found in 1.5% of women undergoing HSG,<ref name="Dmowski">{{cite journal |author=Dmowski WP, Greenblatt RB. |title=Asherman's syndrome and risk of placenta accreta |journal=Obstet Gynecol |volume=34 |issue=2 |pages=288–299. |year=1969 |pmid=5816312 |doi=}}

| |

| </ref> between 5 and 39% of women with recurrent miscarriage<ref name="Rabau">{{cite journal |author=Rabau E, David A. |title=Intrauterine adhesions:etiology, prevention, and treatment |journal=Obstet Gynecol |volume=22 |pages=626–629. |year=1963 |pmid=14082285 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="Toaf">{{cite journal |author=Toaff R. |title=Some remarks on posttraumatic uterine adhesions.in French |journal=Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet |volume=61 |issue=7 |pages=550–552. |year=1966 |pmid=5940506 |doi=}}

| |

| </ref><ref name="Ventolini">{{cite journal |author=Ventolini G, Zhang M, Gruber J. |title=Hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with recurrent pregnancy loss: a cohort study in a primary care population |journal=Surg Endosc |volume=18 |issue=12 |pages=1782–1784. |year=2004 |pmid=15809790 |doi=10.1007/s00464-003-8258-y}}</ref> and up to 40% of patients who have undergone D&C for retained products of conception.<ref name="Westendorp">{{cite journal |author=Westendorp ICD, Ankum WM, Mol BWJ, Vonk J. |title=Prevalence of Asherman's syndrome after secondary removal of placental remnants or a repeat curettage for incomplete abortion |journal=Hum Reprod |volume=13 |issue=12 |pages=3347–3350. |year=1998 |pmid=9886512 |doi=10.1093/humrep/13.12.3347}}

| |

| </ref>

| |

| == Diagnosis ==

| |

| The history of a [[pregnancy]] event followed by a D&C leading to secondary amenorrhea is typical. Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis.<ref name="Valle">Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Intrauterine adhesions: hysteroscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment, and reproductive outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 158:1459-1470.</ref> Imaging by [[sonohysterography]] or [[hysterosalpingography]] will reveal the extent of the scar formation. Ultrasound is not a reliable method of diagnosing Asherman's Syndrome. Hormone studies show normal levels consistent with reproductive function.

| |

|

| |

|

| == Treatment == | | ==[[Asherman's syndrome natural history, complications and prognosis|Natural History, Complications and Prognosis]]== |

| Fertility can be restored by removal of adhesions, depending on the severity of the initial trauma and other individual patient factors. Fluoroscopically guided operative [[hysteroscopy]] is used for visual inspection of the uterine cavity and dissection of scar tissue ([[adhesiolysis]]). In more severe cases, laparoscopy is used in addition to hysteroscopy as a protective measure against uterine perforation. Microscissors are usually used to cut adhesions. Electrocauterization is not recommended.<ref name="Kodaman">{{cite journal |author=Kodaman PH, Arici AA. |title=Intra-uterine adhesions and fertility outcome: how to optimize success? |journal=Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol |volume=19 |issue=3 |pages=207–214. |year=2007 |pmid=17495635 |doi=}}

| |

| </ref> Sometimes a balloon stent such as a [http://www.cookmedical.com/wh/dataSheet.do?id=4488 Cook Medical Balloon Uterine Stent] filled with saline is inserted in the uterus for up to 3 weeks to keep the walls of the uterus apart as they heal to prevent the reformation of adhesions.

| |

|

| |

|

| Hormonal therapy with synthetic or conjugated [[estrogen]] is usually prescribed following surgery to stimulate endometrial growth thereby preventing the walls of the uterus from re-adhering.

| | == Diagnosis == |

|

| |

|

| More studies are needed to evaluate which method of treatment is most likely to have a successful outcome.

| | [[Asherman's syndrome history and symptoms| History and Symptoms]] | [[Asherman's syndrome physical examination | Physical Examination]] | [[Asherman's syndrome laboratory findings | Laboratory Findings]] | [[Asherman's syndrome ultrasound|Ultrasound]] | [[Asherman's syndrome other imaging findings|Other imaging findings]] | [[Asherman's syndrome other diagnostic studies|Other diagnostic studies]] |

|

| |

|

| Follow-up tests (HSG, hysteroscopy or SHG) are necessary to ensure that scars have not reformed. Further surgery may be necessary to restore a normal uterine cavity.

| | ==Treatment== |

| According to a recent study among 61 patients, the overall rate of adhesion recurrence was 27.9% and in severe cases this was 41.9%.<ref name="yu">{{cite journal |author=Yu D, Li T, Xia E, Huang X, Peng X. |title=Factors affecting reproductive outcome of hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for Asherman's syndrome |journal=Fertility and Sterility |volume=89 |issue=3 |pages=715–722 |year=2008 |pmid=17681324 |doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.070}}</ref> Another study found that postoperative adhesions reoccur in close to 50% of severe Asherman's and in 21.6% of moederate cases.<ref name="Valle">Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Intrauterine adhesions: hysteroscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment, and reproductive outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 158:1459-1470.

| | [[Asherman's syndrome medical therapy|Medical therapy]] | [[Asherman's syndrome surgery|Surgery]] | [[Asherman's syndrome primary prevention|Primary prevention]] | [[Asherman's syndrome secondary prevention|Secondary prevention]] | [[Asherman's syndrome cost-effectiveness of therapy|Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy]] | [[Asherman's syndrome future or investigational therapies|Future or Investigational Therapies]] |

| </ref> Mild IUA unlike moderate to severe synechiae do not appear to reform.

| |

|

| |

|

| == Prognosis == | | ==Case Studies== |

| The extent of scar formation is critical. Small scars can usually be treated with success. Extensive obliteration of the uterine cavity or fallopian tube openings ([[ostia]]) may require several surgical interventions or even be uncorrectable. In this case [[surrogacy]], [[IVF]] or [[adoption]] may be advised.

| | [[Asherman's syndrome case study one|Case #1]] |

|

| |

|

| Patients who carry a [[pregnancy]] after correction of Asherman's syndrome may have an increased risk of having abnormal placentation including [[placenta accreta]]<ref name="Fernandez">{{cite journal |author=Fernandez H, Al Najjar F, Chauvenaud-Lambling et al. |title=Fertility after treatment of Asherman's syndrome stage 3 and 4 |journal=J Minim Invasive Gynecol |volume=13 |issue=5 |pages=398–402. |year=2006 |pmid=16962521 |doi=10.1016/j.jmig.2006.04.013}}</ref> where the placenta invades the [[uterus]] more deeply, leading to complications in placental separation after delivery. Premature delivery,<ref name="Roge">{{cite journal |author=Roge, P |title=Hysteroscopic management of uterine synechiae: a series of 102 observations |journal=Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol |volume=65 |issue=2 |pages=189–193. |year=1996 |pmid=8730623 |doi=10.1016/0301-2115(95)02342-9}}</ref> second-trimester pregnancy loss,<ref name="Capella">{{cite journal |author=Capella-Allouc S, Morsad F, Rongieres-Bertrand C, et al. |title=Hysteroscopic treatment of severe Asherman's syndrome and subsequent fertility |journal=Hum Reprod |volume=14 |issue=5 |pages=1230–1233. |year=1999 |pmid=10325268 |doi=10.1093/humrep/14.5.1230}}</ref> and uterine rupture<ref name="Deaton">{{cite journal |author=Deaton JL, Maier D, Andreoli J. |title=Spontaneous uterine rupture during pregnancy after treatment of Asherman's syndrome |journal=Am J Obstet Gynecol |volume=160 |issue=(5Pt1) |pages=1053–1054. |year=1989 |pmid=2729381 |doi=}}</ref> are other reported complications. They may also develop [[incompetent cervix]] where the cervix can no longer support the growing weight of the fetus, the pressure causes the placenta to rupture and the mother goes into premature labour. [[Cerclage]] is a surgical stitch which helps support the cervix if needed.<ref name="Capella">Capella-Allouc S, Morsad F, Rongieres-Bertrand C, et al. Hysteroscopic treatment of severe Asherman's syndrome and subsequent fertility. Hum Reprod; 14:1230-1233.</ref>

| | {{WH}} |

| | | {{WS}} |

| The overall pregnancy rate after adhesiolysis was 60% and the live birth rate was 38.9% according to one study.<ref name="Siegler">{{cite journal |author=Siegler AM, Valle RF. |title=Therapeutic hysteroscopic procedures |journal=Fertil Steril |volume=50 |issue=5 |pages=685–701. |year=1988 |pmid=3053254 |doi=}}

| |

| </ref> Success is related to the severity of the adhesions with 93, 78, and 57% pregnancies achieved after treatment of mild, moderate and severe adhesions, respectively and resulting in 81, 66, and 32% live birth rates, respectively.<ref name="Valle">Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Intrauterine adhesions: hysteroscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment, and reproductive outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 158:1459-1470.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Age is another factor contributing to fertility outcomes after treatment of Asherman's. For women under 35 years of age treated for severe adhesions, pregnancy rates were 66.6% compared to 23.5% in women older than 35.<ref name="Fernandez">Fernandez H, Al-Najjar F, Chauveneaud-Lambling A, et al. Fertility after treatment of Asherman's syndrome stage 3 and 4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2006; 13:398-402.

| |

| </ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Prevention==

| |

| Asherman's need not be caused by an 'over-aggressive' D&C:the recently pregnant uterus is particularly soft and easily injured. Medical alternatives to D&C for evacuation of retained placenta/products of conception exist including [[misoprostol]] methotrexate and mifepristone. Studies show this less invasive and cheaper method to be efficacious, safe and an acceptable alternative to surgical management for most women.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM |title= National Institute of Child Health Human Development (NICHD) Management of Early Pregnancy Failure Trial. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure |journal=N Engl J Med. |volume=353 |issue=8 |pages=761–9. |year=2005 |pmid=16120856 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="Weeks">{{cite journal |author=Weeks A, Alia G, Blum J, Winikoff B, Ekwaru P, Durocher J, Mirembe F. |title=A randomized trial of misoprostol compared with manual vacuum aspiration for incomplete abortion |journal=Obstet Gynecol. |volume=106 |issue=3 |pages=540–7.|year=2005 |pmid=16135584 |doi=}}</ref> It was suggested as early as in 1993<ref name="Friedler">{{cite journal |author=Friedler S, Margalioth EJ, Karfka I, Yaffe H. |title=Incidence of post-abortionintrauterine adhesions evaluated by hysteroscopy-a prospective study |journal=Hum Reprod |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=442–444 |year=1993 |pmid=8473464 |doi=}}</ref> that the incidence of IUA might be lower following medical evacuation (eg. Misoprostol) of the uterus, thus avoiding any intrauterine instrumentation. So far, one study supports this proposal, showing that women who were treated for missed miscarriage with misoprostol did not develop IUA, while 7.7% of those undergoing D&C did.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Tam WH, Lau WC, Cheung LP, Yuen PM, Chung TK. |title=Intrauterine adhesions after conservative and surgical management of spontaneous abortion |journal=J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=182–185 |year=2002 |pmid=11960045 |doi=10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60129-6}}</ref> The advantage of misoprostol is that it can be used for evacuation not only following miscarriage, but also following birth for retained placenta or hemorrhaging.

| |

| | |

| Alternatively, D&C could be performed under ultrasound guidance rather than blind procedure. This would enable the surgeon to end scraping the lining when all retained tissue has been removed, avoiding injury.

| |

| | |

| Early monitoring during pregnancy to identify miscarriage can prevent the development of, or as the case may be, the recurrence of Asherman's as adhesions are more likely to occur after a D&C the longer the period after fetal death.<ref name="Schenker">Friedler S, Margalioth EJ, Kafka I, Yaffe H. Incidence of postabortion intra-uterine adhesions evaluated by husteroscopy: a prospective study. Hum Reprod 1993;8:442-444.</ref> Therefore immediate evacuation following fetal death may prevent IUA.

| |

| | |

| The use of hysteroscopic surgery instead of D&C to remove retained products of conception or placenta is another alternative, although it could be ineffective if tissue is abundant. Also, hysteroscopy is not a widely or routinely-used technique and requires expertise.

| |

| | |

| There is no data to indicate that suction D&C is less likely than sharp curette to result in Asherman's. A recent article describes three cases of women who developed intrauterine adhesions following manual vacuum aspiration.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dalton VK, Saunders NA, Harris LH, Williams JA, Lebovic DI|title=Intrauterine adhesions after manual vacuum aspiration for early pregnancy failure|journal=Fertil. Steril. |volume=85 |issue=6 |pages=1823.e1–3. |year= 2006 |pmid=16674955 |doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.065}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| == History ==

| |

| It was first described in 1894 by [[Heinrich Fritsch]] (Fritsch, 1894)<ref>>{{WhoNamedIt|synd|1521}}Fritsch H, Ein Fall von volligem Schwaund der Gebormutterhohle nach Auskratzung. Zentralbl Gynaekol 1894; 18:1337-1342.

| |

| </ref> and further characterized by the gynecologist [[Joseph Asherman]] in 1948.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Asherman JG. |title=Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions |journal=J Obstet Gynaecol Br Em |volume=55 |issue=2 |pages=2–30. |year=1948. |pmid=

| |

| |doi=}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| It is also known as Fritsch syndrome, or Fritsch-Asherman syndrome.

| |

| | |

| ==References==

| |

| {{Reflist}}

| |

| | |

| == External links ==

| |

| *[http://www.drjasonabbott.com.au/pdfs/Ashermans%20Syndrome.pdf Asherman's syndrome information by Dr Jason Abbott]

| |

| *[http://docinthemachine.com/2006/11/13/new-infertility-becomes-aub-device/ A rare form of Asherman's syndrome Dr Steven Palter]

| |

| | |

| {{Diseases of the pelvis, genitals and breasts}} | |

|

| |

|

| | [[Category:Overview complete]] |

| | [[Category:Disease]] |

| | [[Category:Obstetrics]] |

| | [[Category:Gynecology]] |

| | [[Category:Surgery]] |

| [[Category:Fertility]] | | [[Category:Fertility]] |

| [[Category:Surgery]]

| |

| [[Category:Pregnancy and birth]]

| |

| [[Category:Pregnancy complications]]

| |

| [[Category:Obstetrics]]

| |

| [[Category:D&C]]

| |

| [[Category:Miscarriage]]

| |

| [[Category:Abortion]] | | [[Category:Abortion]] |

| [[Category:Gynecology]]

| |

| [[Category:Pregnancy]]

| |

|

| |

| [[de:Synechie]]

| |

| [[fr:Synéchie]]

| |

| [[hr:Sinehija]]

| |

| [[it:Sindrome di Asherman]]

| |

| [[he:תסמונת אשרמן]]

| |

| [[nl:Syndroom van Asherman]]

| |

| [[pl:Zespół Ashermana]]

| |

|

| |

| {{SIB}}

| |

| {{WH}}

| |

| {{WS}}

| |