Mohs surgery

|

WikiDoc Resources for Mohs surgery |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Mohs surgery Most cited articles on Mohs surgery |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Mohs surgery |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Mohs surgery at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Mohs surgery at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Mohs surgery

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Mohs surgery Discussion groups on Mohs surgery Patient Handouts on Mohs surgery Directions to Hospitals Treating Mohs surgery Risk calculators and risk factors for Mohs surgery

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Mohs surgery |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: Michel C. Samson, M.D., FRCSC, FACS [1]

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Mohs surgery, also known as chemosurgery, created by a general surgeon, Dr. Fredrick E. Mohs, is microscopically controlled surgery that is highly effective for common types of skin cancer, with a cure rate cited by most studies between 97% and 99.8%[1] for primary basal cell carcinoma, the most common type of skin cancer. Mohs procedure is also used for squamous cell carcinoma, but with a lower cure rate. Two isolated studies reported cure rate for primary basal cell cancer as low as 95% and 96% (see discussion on "Why is the Cure Rate so Varied?).[2][3][4] Recurrent basal cell cancer has a lower cure rate with Mohs surgery, more in the range of 94%.[5] It has been used in the removal of melanoma-in-situ (cure rate 77% to 98% depending on surgeon), and certain types of melanoma (cure rate 52%).[6][7] Another study of melanoma-in-situ revealed Mohs cure rate of 95% for frozen section Mohs, and 98 to 99% for fixed tissue Mohs method.[8][9] Other indications for Mohs surgery include dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keratoacanthoma, spindle cell tumors, sebaceous carcinomas, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, merkel cell carcinoma, Pagets's disease of the breast, atypical fibroxanthoma, leimyosarcoma, and angiosarcoma.[10] Because the Mohs procedure is micrographically controlled, it provides precise removal of the cancerous tissue, while healthy tissue is spared. Mohs surgery is relatively expensive when compared to other surgical modalities.[11] However, in anatomically important areas (eyelid, nose, lips), tissue sparing and low recurrence rate makes it a procedure of choice by many physicians.

History

Originally, Dr. Mohs used an escharotic agent made of zinc chloride and bloodroot (the root of the plant Sanguinaria canadensis, which contains the alkaloid sanguinarine). The original ingredients were 40.0 gm Stibnite, 10.0 gm Sanguinaria canadensis, and 34.5 ml of saturated zinc chloride solution.[12] This paste is very similar to "Hoxsey's paste" (see Hoxsey Therapy). Harry Hoxsey, a lay cancer specialist was developing a herbal tonic and paste designed to treat internal and external cancers. Hoxsey recommended applying paste to the affected area and within days to weeks, the area would necrose (cell death), separate from surrounding tissue and fall out. Dr. Mohs applied a very similar paste after experimenting with a number of compounds to the wound of his skin cancer patients. They were to leave the paste on the wound overnight, and the following day, the skin cancer and surrounding skin would be anesthetic, and ready to be removed. The specimen was then excised, and the tissue examined under the microscope. If cancer remained, more paste was applied, and the patient would return the following day. Later, local anesthetic and frozen section histopathology applied to fresh tissue allowed the procedure to be performed the same day, with less tissue destruction, and similar cure rate.[13] The term "chemosurgery" remains today, and is used synonymously with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Mohs procedure

The Mohs procedure is essentially a pathology sectioning method that allows for the complete examination of the surgical margin. It is different from the standard bread loafing technique of sectioning,[14] where random samples of the surgical margin is examined.[15][16]

Mohs surgery is performed in four steps:

- Surgical removal of tissue (Surgical Oncology)

- Mapping the piece of tissue, freezing and cutting the tissue between 5 and 10 micrometers using a cryostat, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or other stains (including T. Blue)

- Interpretation of microscope slides (Pathology)

- Reconstruction of the surgical defect (Reconstructive Surgery)

The procedure is usually performed in a physician's office under local anesthetic. A small scalpel is utilized to cut around the visible tumor. A very small surgical margin is utilized, usually with 1 to 1.5 mm of "free margin" or uninvolved skin. The amount of free margin removed is much less than the usual 4 to 6 mm required for the standard excision of skin cancers.[17] After each surgical removal of tissue, the specimen is processed, cut on the cryostat and placed on slides, stained with H&E and then read by the Mohs surgeon/pathologist who examines the sections for cancerous cells. If cancer is found, its location is marked on the map (drawing of the tissue) and the surgeon removes the indicated cancerous tissue from the patient. This procedure is repeated until no further cancer is found.

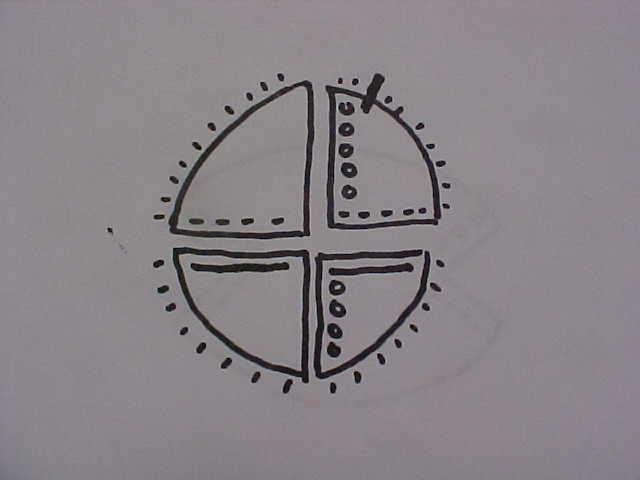

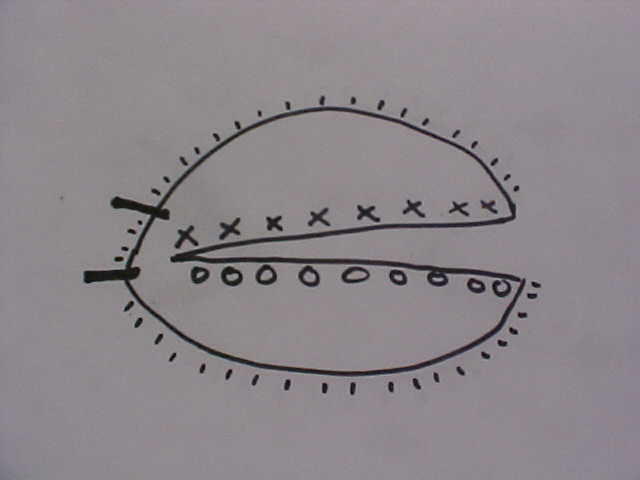

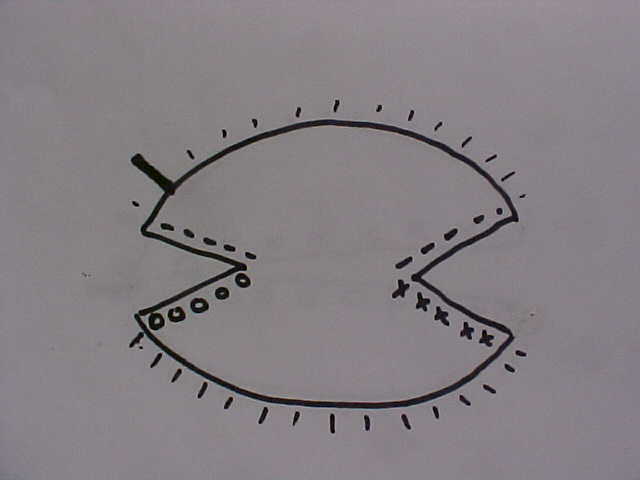

The method is well described in current references.[18][19][20] The mapping combined with the unique "smashing the pie pan" method of processing is the essential of Mohs surgery. If one imagines an aluminum pie pan as the blood covered surgical margin, and the top of the pie is the crust covered surface of the skin - the goal is to flatten the aluminum pie pan into one flat sheet, mark it, stain it, and examine it under the microscope. Another author uses the example of peeling the skin off an orange.[21] Imagine an orange cut in half as the Mohs layer. The peel is the surgical margin. One remove this peel and flatten it out on a glass slide to examine the roots of the invasive cancer. The mapping is simply how one stains and labels the sections for a microscopic examination. The sections can be processed in one piece[22] (using relaxing incisions at multiple points, or hemisectioned like a "Pac-Man" figure),[23] cut in halves, cut in quarters, or cut in multiple pieces. Single piece processing is acceptable for small cancers, and multiple piece sectioning facilitates processing and prevent artifacts. Single piece sectioning prevents errors introduced by soft, hard-to-handle tissue; or from accidental dropping or mislabeling of specimen. Multiple sectioning prevents compression artifacts, separation of tissue, and other logistical problems with handling large thin sheets of frozen skin.

Some physicians believe that frozen section histology is the same as Mohs micrographic surgery, and it is not.[24] Mohs surgery is performed using fresh tissue and frozen section histology. However, standard frozen section histology usually utilizes a random tissue sampling technique called "bread loafing". Bread loafing is a statistical sampling method which exams less than 5% of the total surgical margin (imagine pulling 5 slices of bread out of a whole loaf of sliced bread and examining only those 5 slices to visualize the whole loaf). In Mohs processing, the entire surgical margin is examined (imagine one who examined the entire outside crust of the same loaf of bread). In statistical terms, the more slices of bread one examines, the lower the "false negative" rate will become.[25] False negatives occur when a pathologist reads cancer excision as "free of residual carcinoma", even though cancer might be present in the wound and missed because of the random sampling.[26] In reality, most pathology labs examine only 3 to 8 sections of the "loaf" in their margin determination. While a diligent pathologist can cut and process a standard excision to get the same margin control as Mohs surgery, it is seldom done since tissue processing is very difficult in practice. The alternative to Mohs surgery is when a pathologist requests the processing to be done by "cutting through the block". Again, this method approaches that of Mohs surgery, but still is not as good. Cutting through the block will result in the random discarding of many slices, but does greatly decrease the incidence of "false negative" reports. Dr. Mohs perfected a simple and efficient way to "flatten" and examine the entire surgical margin.

Staining Convention

Each surgeon has their own convention. A typical convention is as follows[27]

Epidermis l l l l l l l l l l BLUE - - - - - - - - - RED --------------------------------- YELLOW O O O O O O O GREEN X X X X X X X Missing Epidermis V V V V V V V V V V

Mohs Surgery Case Studies

Photos courtesy of Dr. B. Cowan

CASE STUDY 1: Left Nasal Rim Skin Cancer

File:Mohs surgery case study 1.png

Click to view complete slide-show and the surgeon's comments for the Left Nasal Rim Skin Cancer case study

CASE STUDY 2: Right Lower Lip Skin Cancer

File:Mohs surgery case study 2.png

Click to view complete slide-show and the surgeon's comments for the Right Lower Lip Skin Cancer case study

CASE STUDY 3: Left Temple Basal Cell Cancer

File:Mohs surgery case study 3.png

Click to view complete slide-show and the surgeon's comments for the Left Temple Basal Cell Cancer case study

About Mohs surgeons

The Mohs surgeon must understand the biologic behavior of several types of skin tumors in order to provide comprehensive management of cutaneous oncology. The Mohs surgeon must have extensive training in the surgical removal of skin cancer, the microscopic analysis (pathology) of the tumor, and reconstructive surgery of the skin and underlying structures. In addition, Medicare requires that the same physician serve as surgeon and pathologist. All Mohs surgeons must have a CLIA certified laboratory.

The American College of Mohs Micrographic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology was established in 1967 and named after Frederic Mohs, who first developed the technique in the 1940s. This organization's members are board certified dermatologists who have become proficient and experienced in the use of Mohs micrographic surgery. In order to become a member of this college, member physicians must be board certified in a field of medicine or surgery (usually dermatology) and then complete an additional 1 to 2 years of post-residency fellowship training, with exposure to complex tumors and reconstructive plastic surgery of the skin. These College sponsored fellowships are not recognized by the The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The College has grown to nearly 800 members.

The American Society for Mohs Surgery is a non-profit professional medical society of over 800 dermatologists, pathologists, and Mohs technicians. Founded in 1990, the ASMS is dedicated to the highest quality patient care and education relative to Mohs surgery as a specialized surgical treatment for skin cancer. This organization's Fellows are board certified dermatologists who have become proficient and experienced in the use of Mohs micrographic surgery. Some ASMS Fellows have completed an ACMMSCO sponsored Mohs fellowship, but most received their Mohs training during Dermatology Residency and post-residency training and experience. ASMS requires yearly peer case review of its Fellow members.

The Board of Medical Subspecialities considers Mohs micrographic surgery as part of the field of dermatology and does not recognize it as a separate subspeciality.

The American Academy of Dermatology is the largest organization of board certified dermatologists, many of whom perform dermatologic and Mohs micrographic surgery. With a membership of over 15,000, it represents virtually all practicing dermatologists in the United States and Canada and has specific member information regarding those performing Mohs micrographic surgery.

The American Society of Dermatologic Surgery founded in 1970 is the largest organization of board certified dermasurgeons with nearly 4000 members who perform dermatologic surgeries including Mohs micrographic surgery. The mission of the Society is to promote excellence in the subspecialty of dermatologic surgery and foster the highest standards of patient care.

The official medical journal for Mohs surgery, Dermatologic Surgery, is published by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and is the official journal of The American College of Mohs Micrographic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology and the official publication for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education is responsible for the accreditation of post-MD medical training programs within the United States. Accreditation is accomplished through a peer review process and is based upon established standards and guidelines. Starting in 2005, and ACGME recognized and accredited Procedural Dermatology fellowships have started in the U.S. to train fellows. There is no additional ABMS board certification of dermatologists who have completed a Procedural Dermatology fellowship.

The Association of Academic Dermatologic Surgoens has board certified dermasurgeon professors who have faculty appointments at major teaching hospitals and universities and are engaged in training medical students and residents in the practice of dermatologic surgery and Mohs micrographic surgery.

Patients who desire Mohs surgery for removal of skin cancer should contact a Mohs surgeon for evaluation and treatment of the biopsied lesion.

References

- Bowen G, White G, Gerwels J (2005). "Mohs micrographic surgery". Am Fam Physician. 72 (5): 845–8. PMID 16156344.Full text

See also

External links

- American Academy of Dermatology

- American Society of Dermatologic Surgery

- Mohs Micrographic Surgery as a Skin Cancer Therapy (Case studies/before and after images included)

- Society of Mohs Surgery About Skin Cancer

- Academic Dermasurgeons

- Mohs College - about skin surgery

- About Mohs in Argentina

- "Mohs math..." an open access paper with excelent animations useful for teaching tissue movement that occurs in Mohs Surgery

- [3]

nl:Mohs' chirurgie Template:WikiDoc Sources

- ↑ George, R. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, W.B. Saunders Co., p. 13.

- ↑ Smeets NW, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs' micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. November 13, 2004-19;364(9447):1766-72.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15541449?dopt=Abstract

- ↑ Wennberg, AM., et al. Five-year results of Mohs' micrographic surgery for aggressive facial basal cell carcinoma in Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999 Sep;79(5):370-2.

- ↑ George, R. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, W.B. Saunders Co., p. 7.

- ↑ Mikhail, G. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, W.B. Saunders. p 4.

- ↑ Gross, K.G., et al. Mohs Surgery, Fundamentals and Techniques. 1999, Mosby. pp.211-220

- ↑ Bene, NI, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery is accurate 95.1% of the time for melanoma in situ: a prospective study of 167 cases Dermatol Surg. 2008 May;34(5):660-4.

- ↑ Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):151-64.Links Lentigo maligna: prognosis and treatment options. Stevenson O, Ahmed I.

- ↑ Gross, K.G., et al. Mohs Surgery, Fundamentals and Techniques. 1999, Mosby. pp. 193-203.

- ↑ http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_4X_Treatment_of_Basal_Cell_Carcinoma_51.asp

- ↑ Mohs, F. Chemosurgery, Microscopically Controlled Surgery for Skin cancer. 1978, Charles C. Thomas Publisher. ISBN 0-398-03725-6. pp. 3-6.

- ↑ Mikhail, G. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, Saunders. pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Maloney, M.E. et. al. Surgical Dermatopathology. Blackwell Science, 1999. p. 112-113.

- ↑ Mikhail, G. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, Saunders, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Bowen G, White G, Gerwels J, = Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 2005. 72(5) pages = 845–8.Full text

- ↑ http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/CancerManagementGuidelines/Skin/NonMelanoma/ManagementPolicies/start.htm

- ↑ Maloney, M.E. et. al. Surgical Dermatopathology. Blackwell Science, 1999. p. 1111-117.

- ↑ Gross, K.G., et al. Mohs Surgery, Fundamentals and Techniques. 1999, Mosby. pp.49-66

- ↑ Mikhail, G.R., Mohs Micrographic Surgery. 1991, WB Saunders. pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Maloney, et al. Surgical Dermatopathology. p. 113

- ↑ Gross, et al. Mohs Surgery. p. 83-84.

- ↑ Gross, et. al. Mohs Surgery. p. 86-89.

- ↑ Maloney, M.E. et. al. Surgical Dermatopathology. Blackwell Science, 1999. p. 116.

- ↑ Maloney, M.E. et. al. Surgical Dermatopathology. Blackwell Science, 1999. p. 114.

- ↑ Maloney, M.E. et. al. Surgical Dermatopathology. Blackwell Science, 1999. p. 118.

- ↑ Mikhail, et al. p 21