Celiac disease pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

===HLA genetic typing=== | ===HLA genetic typing=== | ||

Antibody testing and [[Human leukocyte antigen|HLA]] testing have similar accuracies.<ref name="pmid17785484"/> | Antibody testing and [[Human leukocyte antigen|HLA]] testing have similar accuracies.<ref name="pmid17785484"/> | ||

===Pathology=== | ===Pathology=== | ||

Revision as of 02:11, 31 August 2012

|

Celiac disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Medical Therapy |

|

Case Studies |

|

Celiac disease pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Celiac disease pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Celiac disease pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Celiac disease is caused by a reaction to gliadin, a gluten protein found in wheat (and similar proteins of the tribe Triticeae which includes other cultivars such as barley and rye). Upon exposure to gliadin, the enzyme tissue transglutaminase modifies the protein, and the immune system cross-reacts with the bowel tissue, causing an inflammatory reaction. That leads to flattening of the lining of the small intestine, which interferes with the absorption of nutrients. The only effective treatment is a lifelong gluten-free diet.

Pathophysiology

Coeliac disease appears to be polyfactorial, both in that more than one abnormal factor can cause the disease and also more than one factor is necessary for the disease to manifest in a patient.

Most all coeliac patients have abnormal HLA DQ2 allele. However, about 20–30% of people without coeliac disease have inherited an abnormal HLA-DQ2 allele. This suggests additional factors are needed for coeliac disease to develop. Furthermore, about 5% of those people who do develop coeliac disease do not have the DQ2 gene.

The HLA-DQ2 allele shows incomplete penetrance, as the gene alleles associated with the disease appear in most patients, but are neither present in all cases nor sufficient by themselves cause the disease.

Role of other grains

Wheat varieties or subspecies containing gluten such as spelt and Kamut®, and the rye/wheat hybrid triticale, also trigger symptoms.[1]

Barley and rye also induce symptoms of coeliac disease.[1] A small minority of coeliac patients also react to oats.[2][3] Most probably oats produce symptoms due to cross contamination with other grains in the fields or in the distribution channels. There is at least one oat vendor, Gluten Free Oats®, that offers oats that can be considered SAFE for people who are gluten intolerant because they are tested to be below 10 parts per million (ppm) by the University of Nebraska FARRP Laboratory [4]. Another vendor (McCann's) which, while not claiming to be gluten-free, points out that the risk of contamination from their Oats product is low due to the processes they use.[5] Other cereals, such as maize (corn), quinoa, millet, sorghum, rice are safe for a patient to consume. Other carbohydrate-rich foods such as potatoes and bananas do not contain gluten and do not trigger symptoms.

HLA genetic typing

Antibody testing and HLA testing have similar accuracies.[6]

Pathology

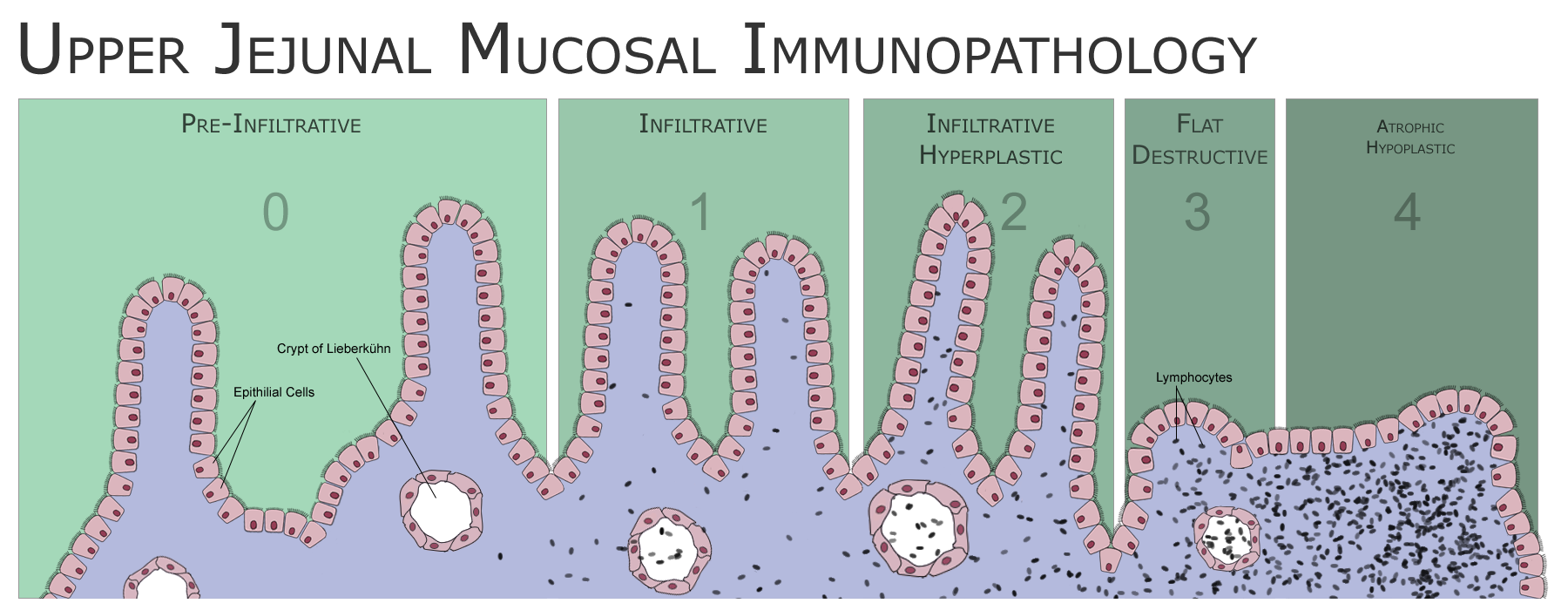

The classic pathology changes of coeliac disease in the small bowel are categorized by the "Marsh classification":[7]

- Marsh stage 0: normal mucosa

- Marsh stage 1: increased number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes, usually exceeding 20 per 100 enterocytes

- Marsh stage 2: proliferation of the crypts of Lieberkuhn

- Marsh stage 3: partial or complete villous atrophy

- Marsh stage 4: hypoplasia of the small bowel architecture

The changes classically improve or reverse after gluten is removed from the diet, so many official guidelines recommend a repeat biopsy several (4–6) months after commencement of gluten exclusion.[8]

In some cases a deliberate gluten challenge, followed by biopsy, may be conducted to confirm or refute the diagnosis. A normal biopsy and normal serology after challenge indicates the diagnosis may have been incorrect.[8] Patients are warned that one does not "outgrow" coeliac disease in the same way as childhood food intolerances.

Associated Conditions

- Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM)

- Sjogren’s syndrome

- Thyroid disease

- Dermatitis herpetiformis – extraintestinal manifestation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Grain toxicity" (RTF). The CELIAC list. Retrieved 2006-08-27.

- ↑ Lundin K, Nilsen E, Scott H, Løberg E, Gjøen A, Bratlie J, Skar V, Mendez E, Løvik A, Kett K (2003). "Oats induced villous atrophy in coeliac disease". Gut. 52 (11): 1649–52. PMID 14570737.

- ↑ Størsrud S, Olsson M, Arvidsson Lenner R, Nilsson L, Nilsson O, Kilander A (2003). "Adult coeliac patients do tolerate large amounts of oats". Eur J Clin Nutr. 57 (1): 163–9. PMID 12548312.

- ↑ http://www.glutenfreeoats.com, http://www.farrp.org/, http://www.farrp.org/analysis.htm

- ↑ "McCann's FAQ". Odlum Group. 2004. Retrieved 2006-11-03.

we reckon that the level of non-oat grains to be less than 0.05%

- ↑

- ↑ Marsh M (1992). "Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue')". Gastroenterology. 102 (1): 330–54. PMID 1727768.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1