Granulocytic sarcoma: Difference between revisions

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

*[Disease name] may also be diagnosed using [diagnostic study name]. | *[Disease name] may also be diagnosed using [diagnostic study name]. | ||

*Findings on [diagnostic study name] include [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3]. | *Findings on [diagnostic study name] include [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3]. | ||

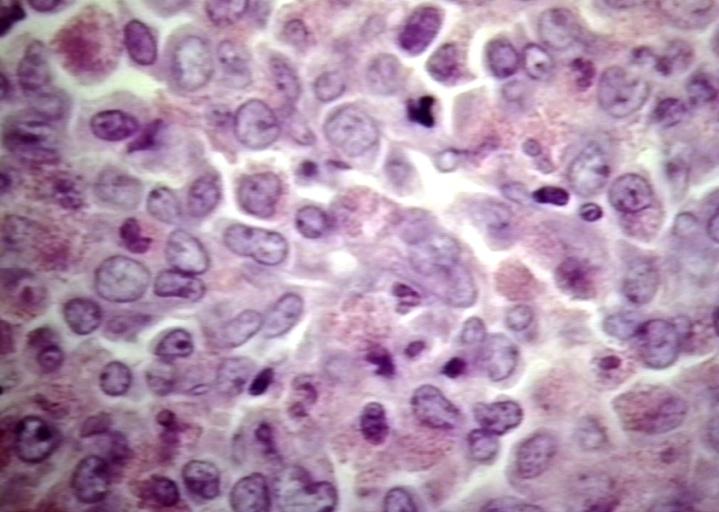

Definitive diagnosis of a chloroma usually requires a [[biopsy]] of the lesion in question. Historically, even with a tissue biopsy, pathologic misdiagnosis was an important problem, particularly in patients without a clear pre-existing diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia to guide the pathologist. In one published series on chloroma, the authors stated that 47% of the patients were initially misdiagnosed, most often as having a malignant [[lymphoma]].<ref>Yamauchi K; Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma: report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the literature. Cancer 2002 Mar 15;94(6):1739-46.</ref> | |||

However, with advances in diagnostic techniques, the diagnosis of chloromas can be made more reliable. Traweek et al. described the use of a commercially available panel of [[monoclonal antibody|monoclonal antibodies]], against [[myeloperoxidase]], [[CD68]], [[CD43]], and [[CD20]], to accurately diagnose chloroma via [[immunohistochemistry]] and differentiate it from lymphoma.<ref>Traweek ST, Arber DA, Rappaport H, et al. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors: an immunohistochemical and morphologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 17:1011-1019, 1993.</ref> The increasingly refined use of [[flow cytometry]] has also facilitated more accurate diagnosis of these lesions. | |||

== Treatment == | == Treatment == | ||

=== Medical Therapy === | === Medical Therapy === | ||

Revision as of 15:09, 13 May 2016

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ammu Susheela, M.D. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: Chloroma, Myeloid Sarcoma, Myeloid Sarcomas, Myeloid Cell Tumor, Granulocytic Sarcoma, Extramedullary Myeloid Cell Tumor

Overview

Historical Perspective

- The condition now known as chloroma was first described by the British physician A. Burns in 1811[1], although the term chloroma did not appear until 1853.[2] This name is derived from the Greek word chloros (green), as these tumors often have a green tint due to the presence of myeloperoxidase. The link between chloroma and acute leukemia was first recognized in 1902 by Dock and Warthin.[3] However, because up to 30% of these tumors can be white, gray, or brown rather than green, the more correct term granulocytic sarcoma was proposed by Rappaport in 1967[4] and has since become virtually synonymous with the term chloroma.

- Currently, any extramedullary manifestion of acute myeloid leukemia can be termed a granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma. Specific terms which overlap with granulocytic sarcoma include:

- Leukemia cutis, describing infiltration of the dermis (skin) by leukemic cells, which is also referred to as cutaneous granulocytic sarcoma.

- Meningeal leukemia, or invasion of the subarachnoid space by leukemic cells, is usually considered distinct from chloroma, although very rarely occurring solid central nervous system tumors composed of leukemic cells can be termed chloromas.

Classification

- [Disease name] may be classified according to [classification method] into [number] subtypes/groups:

- [group1]

- [group2]

- [group3]

- Other variants of [disease name] include [disease subtype 1], [disease subtype 2], and [disease subtype 3].

Pathophysiology

- A granulocytic sarcoma is a solid tumor composed of immature malignant white blood cells called myeloblasts. A chloroma is an extramedullary manifestion of acute myeloid leukemia; in other words, it is a solid collection of leukemic cells occurring outside of the bone marrow.

In acute leukemia

Chloromas are rare; exact estimates of their incidence are lacking, but they are uncommonly seen even by physicians specializing in the treatment of leukemia. Chloromas may be somewhat more common in patients with the following disease features:[5]

- FAB class M4 or M5

- those with specific cytogenetic abnormalities (e.g. t(8;21) or inv(16))

- those whose myeloblasts express T-cell surface markers, CD13, or CD14

- those with high peripheral white blood cell counts

However, even in patients with the above risk factors, chloroma remains an uncommon complication of acute myeloid leukemia. Rarely, a chloroma can develop as the sole manifestation of relapse after apparently successful treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. In keeping with the general behavior of chloromas, such an event must be regarded as an early herald of a systemic relapse, rather than as a localized process. In one review of 24 patients who developed isolated chloromas after treatment for acute myeloid leukemia, the mean interval until bone marrow relapse was 7 months (range, 1 to 19 months).[6]

In myeloproliferative or myelodysplastic syndromes

Chloromas may occur in patients with a diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myeloproliferative syndromes (MPS) (e.g. chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis, or myelofibrosis). The detection of a chloroma is considered de facto evidence that these pre-malignant conditions have transformed into an acute leukemia requiring appropriate treatment. For example, presence of a chloroma is sufficient to indicate that chronic myelogenous leukemia has entered its blast crisis phase.

Primary chloroma

Very rarely, chloroma can occur without a known pre-existing or concomitant diagnosis of acute leukemia or MDS/MPS; this is known as primary chloroma. Diagnosis is particularly challenging in this situation (see below). In almost all reported cases of primary chloroma, acute leukemia has developed shortly afterward (median time to development of acute leukemia 7 months, range 1-25 months). Therefore, primary chloroma should probably be considered an initial manifestation of acute leukemia, rather than a localized process, and treated as such.

Microscopic Pathology

- The pathogenesis of [disease name] is characterized by [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3].

- The [gene name] gene/Mutation in [gene name] has been associated with the development of [disease name], involving the [molecular pathway] pathway.

- On gross pathology, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

Causes

- [Disease name] may be caused by either [cause1], [cause2], or cause3].

- [Disease name] is caused by a mutation in the [gene1], [gene2], or gene3] gene[s].

- There are no established causes for [disease name].

Differentiating [disease name] from other Diseases

- [Disease name] must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [clinical feature 1], [clinical feature 2], and [clinical feature 3], such as:

- [Differential dx1]

- [Differential dx2]

- [Differential dx3]

Epidemiology and Demographics

- The prevalence of [disease name] is approximately [number or range] per 100,000 individuals worldwide.

- In [year], the incidence of [disease name] was estimated to be [number or range] cases per 100,000 individuals in [location].

Age

- Patients of all age groups may develop [disease name].

- [Disease name] is more commonly observed among patients aged [age ange] years old.

- [Disease name] is more commonly observed among [elderly patients/young patients/children].

Gender

- [Disease name] affects men and women equally.

- [Gender 1] are more commonly affected with [disease name] than [gender 2].

- The [gender 1] to [Gender 2] ratio is approximately [number > 1] to 1.

Race

- There is no racial predilection for [disease name].

- [Disease name] usually affects individuals of the [race 1] race.

- [Race 2] individuals are less likely to develop [disease name].

Risk Factors

- Common risk factors in the development of [disease name] are [risk factor 1], [risk factor 2], [risk factor 3], and [risk factor 4].

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- The majority of patients with [disease name] remain asymptomatic for [duration/years].

- Early clinical features include [manifestation 1], [manifestation 2], and [manifestation 3].

- If left untreated, [#%] of patients with [disease name] may progress to develop [manifestation 1], [manifestation 2], and [manifestation 3].

- Common complications of [disease name] include [complication 1], [complication 2], and [complication 3].

- Prognosis is generally [excellent/good/poor], and the [1/5/10year mortality/survival rate] of patients with [disease name] is pproximately [#%].

- There is conflicting evidence on the prognostic significance of chloromas in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. In general, they are felt to augur a poorer prognosis, with a poorer response to treatment and worse survival[7]; however, others have reported that chloromas associate, as a biologic marker, with other poor prognostic factors, and therefore do not have independent prognostic significance.[8]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

- The diagnosis of [disease name] is made when at least [number] of the ollowing [number] diagnostic criteria are met:

- [criterion 1]

- [criterion 2]

- [criterion 3]

- [criterion 4]

Symptoms

- Symptoms of [disease name] may include the following:

- [symptom 1]

- [symptom 2]

- [symptom 3]

- [symptom 4]

- [symptom 5]

- [symptom 6]

Chloromas may occur in virtually any organ or tissue.

- The most common areas of involvement are the skin (also known as leukemia cutis) and the gums.

- Skin involvement typically appears as violaceous, raised, nontender plaques or nodules, which on biopsy are found to be infiltrated with myeloblasts.

- Note that leukemia cutis differs from Sweet's syndrome, in which the skin is infiltrated by mature neutrophils in a paraneoplastic process. Gum involvement (gingival hypertrophy) leads to swollen, sometimes painful gums which bleed easily with tooth brushing and other minor trauma.

- Other tissues which can be involved include lymph nodes, the small intestine, the mediastinum, epidural sites, the uterus, and the ovaries. Symptoms of chloroma at these sites are related to their anatomic location; chloromas may also be asymptomatic and be discovered incidentally in the course of evaluation of a person with acute myeloid leukemia.

- Central nervous system involvement, as described above, most often takes the form of meningeal leukemia, or invasion of the subarachnoid space by leukemic cells. This condition is usually considered separately from chloroma, as it requires different treatment modalities. True chloromas (i.e. solid leukemic tumors) of the central nervous system are exceedingly rare, but has been described.

Physical Examination

- Patients with [disease name] usually appear [general appearance].

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

- [finding 1]

- [finding 2]

- [finding 3]

- [finding 4]

- [finding 5]

- [finding 6]

Laboratory Findings

- There are no specific laboratory findings associated with [disease name].

- A [positive/negative] [test name] is diagnostic of [disease name].

- An [elevated/reduced] concentration of [serum/blood/urinary/CSF/other] [lab test] is diagnostic of [disease name].

- Other laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of [disease name] include [abnormal test 1], [abnormal test 2], and [abnormal test 3].

Imaging Findings

- There are no [imaging study] findings associated with [disease name].

- [Imaging study 1] is the imaging modality of choice for [disease name].

- On [imaging study 1], [disease name] is characterized by [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

- [Imaging study 2] may demonstrate [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

Other Diagnostic Studies

- [Disease name] may also be diagnosed using [diagnostic study name].

- Findings on [diagnostic study name] include [finding 1], [finding 2], and [finding 3].

Definitive diagnosis of a chloroma usually requires a biopsy of the lesion in question. Historically, even with a tissue biopsy, pathologic misdiagnosis was an important problem, particularly in patients without a clear pre-existing diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia to guide the pathologist. In one published series on chloroma, the authors stated that 47% of the patients were initially misdiagnosed, most often as having a malignant lymphoma.[9]

However, with advances in diagnostic techniques, the diagnosis of chloromas can be made more reliable. Traweek et al. described the use of a commercially available panel of monoclonal antibodies, against myeloperoxidase, CD68, CD43, and CD20, to accurately diagnose chloroma via immunohistochemistry and differentiate it from lymphoma.[10] The increasingly refined use of flow cytometry has also facilitated more accurate diagnosis of these lesions.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- There is no treatment for [disease name]; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care.

- The mainstay of therapy for [disease name] is [medical therapy 1] and [medical therapy 2].

- [Medical therapy 1] acts by [mechanism of action1].

- Response to [medical therapy 1] can be monitored with [test/physical finding/imaging] every [frequency/duration].

Surgery

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] in conjunction with [chemotherapy/radiation] is the most common approach to the treatment of [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] can only be performed for patients with [disease stage] [disease name].

Prevention

- There are no primary preventive measures available for [disease name].

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of [disease name] include [measure1], [measure2], and [measure3].

- Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followedup every [duration]. Followupm testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3].

References

- ↑ Burns A. Observations of surgical anatomy, in Head and Neck. London, England, Royce, 1811, p. 364.

- ↑ King A. A case of chloroma. Monthly J Med 17:17, 1853.

- ↑ Dock G, Warthin AS. A new case of chloroma with leukemia. Trans Assoc Am Phys 19:64, 1904, p. 115.

- ↑ Rappaport H. Tumors of the hematopoietic system, in Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Section III, Fascicle 8. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, 1967, pp. 241-247.

- ↑ Byrd JC, Edenfield JW, Shields DJ, et al: Extramedullary myeloid tumours in acute nonlymphocytic leukaemia: A clinical review. J Clin Oncol 13:1800, 1995.

- ↑ Byrd JC, Weiss RB. Recurrent granulocytic sarcoma: an unusual variation of acute myeloid leukemia associated with 8;21 chromosomal translocation and blast expression of the neural cell adhesion molecule. Cancer 73:2107-2112, 1994.

- ↑ Tanravahi R, Qumsiyeh M, Patil S, et al: Extramedullary leukemia adversely affects hematologic complete remission and overall survival in patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22): Results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. J Clin Oncol 15:466, 1997.

- ↑ Bisschop MM, Revesz T, Bierings M, et al: Extramedullary infiltrates at diagnosis have no prognostic significance in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 15:46, 2001.

- ↑ Yamauchi K; Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma: report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the literature. Cancer 2002 Mar 15;94(6):1739-46.

- ↑ Traweek ST, Arber DA, Rappaport H, et al. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors: an immunohistochemical and morphologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 17:1011-1019, 1993.

[[Category:Pick One of 28 Approved