Left ventricular aneurysm pathophysiology

|

Left ventricular aneurysm Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Left ventricular aneurysm from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Left ventricular aneurysm pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Left ventricular aneurysm pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Left ventricular aneurysm pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1];Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [2]

Overview

Aneurysms form when the intraventricular tension stretches the non contracting, infarcted heart muscle, resulting in an expansion of the thin layer of necrotic muscle and fibrous tissue, which bulges with each cardiac contraction. The wall of a mature aneurysm is a white fibrous scar. It becomes more densely fibrotic as the time passes, and bulges outward with each cardiac contraction, resulting in a reduction of the left ventricular stroke volume. On microscopy, hyalinized fibrous tissue is the predominant finding. It usually takes 1 month for fibrous tissue to form.

Pathophysiology

Microscopic findings

- Hyalinized fibrous tissue is the predominant finding.

- However, a small number of viable muscle cells are also usually present.[1]

- It usually takes 1 month for fibrous tissue to form.

Gross Pathology

- The wall of a mature aneurysm is a white fibrous scar.

- The aneurysmal portion of the LV wall is thin. A mural thrombosis (which can be calcified), may be seen attached to the endocardial surface.[3]

- The endocardium beneath retains its trabeculations; the area of scarring is not clearly demarcated from the rest of the wall.

- The wall of the aneurysm becomes more densely fibrotic as the time passes, it bulges outward with each cardiac contraction and compromises the left ventricular stroke volume.

Images

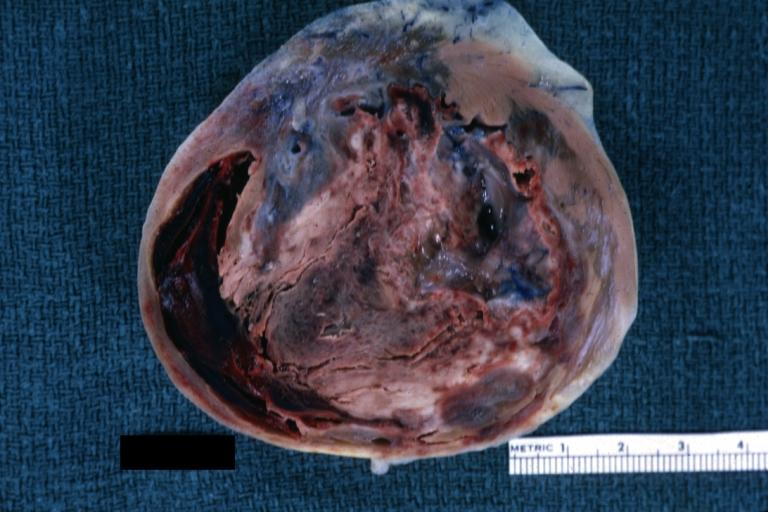

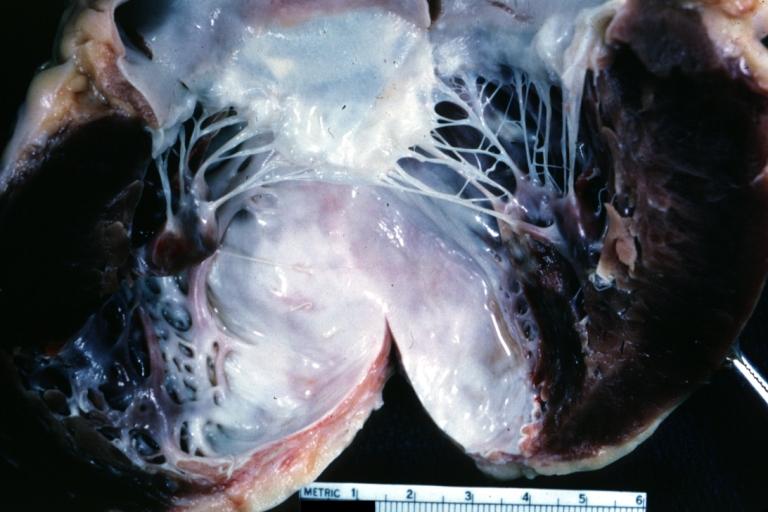

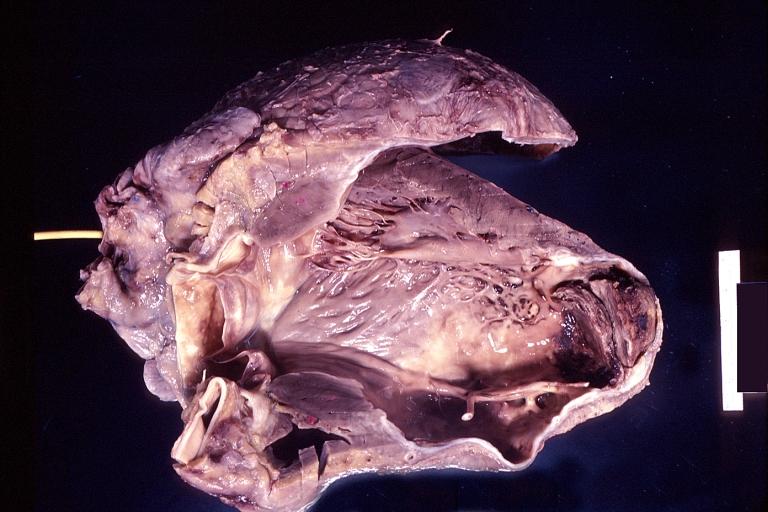

The gross pathologic features of LV aneurysm are shown below.[4]

-

Left ventricular aneurysm

-

Left Ventricular Aneurysm; Gross pathology: The horizontal section shows the apex of the left ventricle with aneurysmal dilation and mural thrombus. A large scar tissue can be seen in the myocardium.

-

Left ventricular aneurysm.

-

Heart; old myocardial infarction with aneurysm formation

References

- ↑ Gorlin R, Klein MD, Sullivan JM (1967). "Prospective correlative study of ventricular aneurysm. Mechanistic concept and clinical recognition". Am. J. Med. 42 (4): 512–31. PMID 6024720.

- ↑ PHARES WS, EDWARDS JE, BURCHELL HB (1953). "Cardiac aneurysms; clinicopathologic studies". Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 28 (9): 264–71. PMID 13056012.

- ↑ Dubnow MH, Burchell HB, Titus JL (1965). "Postinfarction ventricular aneurysm. A clinicomorphologic and electrocardiographic study of 80 cases". Am. Heart J. 70 (6): 753–60. PMID 5842520.

- ↑ Images courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission. © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology