Botulism epidemiology and demographics

|

Botulism Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Botulism epidemiology and demographics On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Botulism epidemiology and demographics |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Botulism epidemiology and demographics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [2]

Overview

Globally, botulism is fairly rare. In the United States, for example, an average of 110 cases are reported each year. Of these, roughly 70% are infant botulism, 25% are foodborne botulism, and 5% are wound botulism. The number of cases of food borne and infant botulism has changed little in recent years, but wound botulism has increased because of the use of black tar heroin, especially in California.[1] Wound botulism may be caused even by inhaled cocaine.

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

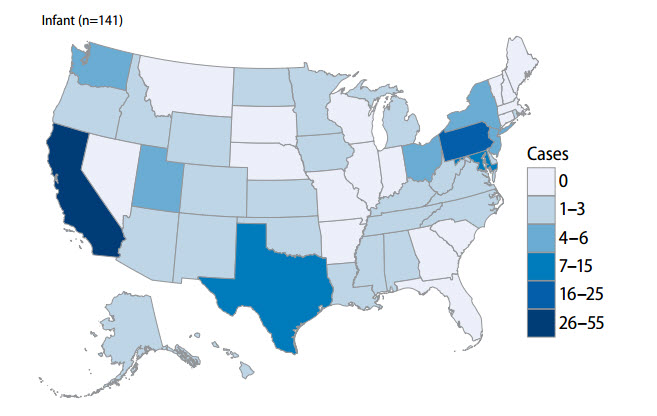

Globally, botulism is fairly rare. In the United States, for example, an average of 110 cases are reported each year. Of these, roughly 70% are infant botulism, 25% are foodborne botulism, and 5% are wound botulism. Infant botulism is predominantly sporadic and not associated with epidemics, but great geographic variability exists.[2] Approximately, a total number of 900 cases of infant botulism has been reported in the United States. From 1974 to 1996, for example, 47.2% of all infant botulism cases reported in the U.S. occurred in California.

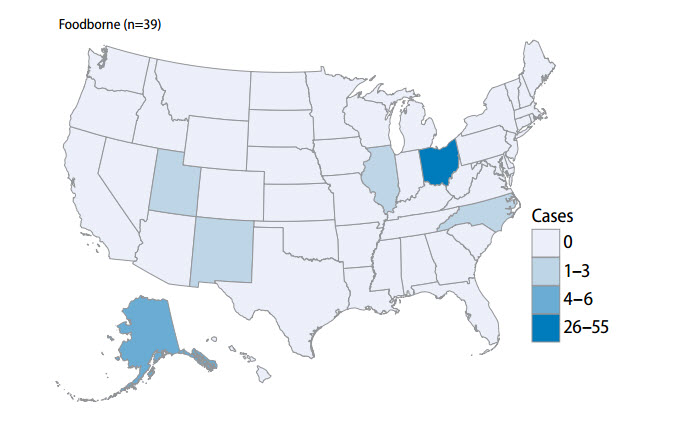

Between 1990 and 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 263 individual foodborne cases from 160 botulism events in the United States with a case-fatality rate of 4%. Thirty-nine percent (103 cases and 58 events) occurred in Alaska, all of which were attributable to traditional Alaska aboriginal foods. In the lower 49 states, home-canned food was implicated in 70 (91%) events with canned asparagus being the most numerous cause. Two restaurant-associated outbreaks affected 25 persons. The median number of cases per year was 23 (range 17–43), the median number of events per year was 14 (range 9–24). The highest incidence rates occurred in Alaska, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. All other states had an incidence rate of 1 case per ten million people or less.[3]

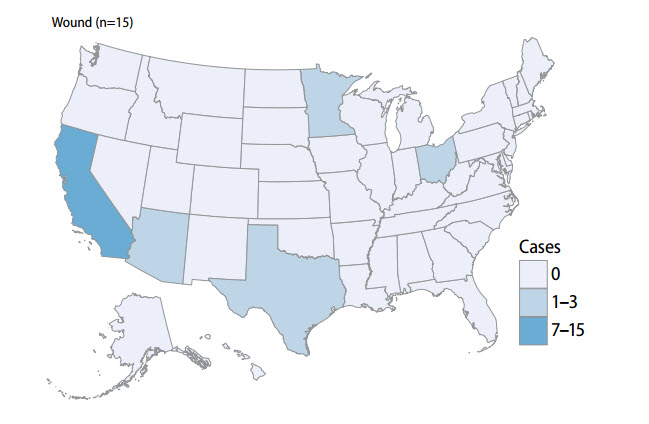

The number of cases of food borne and infant botulism has changed little in recent years, but wound botulism has increased because of the use of black tar heroin, especially in California.[1] Wound botulism may be caused even by inhaled cocaine.

Outbreaks

The following table, summarizes foodborne botulism outbreaks.[4][5][6][7][8] Outbreaks defined as two or more cases resulting from a common exposure.

|

Race

There is no racial predilection of botulism.

Gender

Men and women are affected equally with botulism.

Age

- Infant botulism: Occurs in infants younger than 12 month of old.

- Foodborne and wound botulism: May occur in any ages.

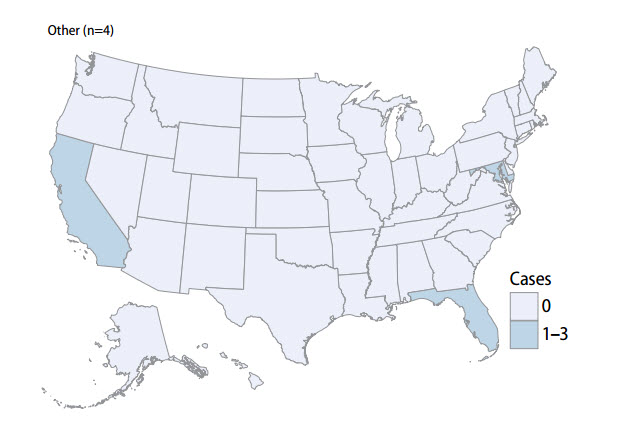

Number of confirmed botulism cases by state and transmission category in the United States, 2015

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Passaro, Douglas J.; Werner, Benson; McGee, Jim; Mac Kenzie, William R.; Vugia, Duc J. (1998). "Wound Botulism Associated With Black Tar Heroin Among Injecting Drug Users". JAMA. 279 (11): 859–63. doi:10.1001/jama.279.11.859. PMID 9516001.

- ↑ Pickett J, Berg B, Chaplin E, Brunstetter-Shafer MA (1976). "Syndrome of botulism in infancy: clinical and electrophysiologic study". N. Engl. J. Med. 295 (14): 770–2. doi:10.1056/NEJM197609302951407. PMID 785257.

- ↑ {{Cite journal |last=Sobel |first=Jeremy |publisher=Centers for Disease Control |date= September 2004 |title=Foodborne Botulism in the United States, 1990–2000 |url=http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no9/03-0745.htm |accessdate=September 29, 2010 |postscript=

- ↑ "Botulism from home-canned bamboo shoots--Nan Province, Thailand, March 2006". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (14): 389–92. 2006. PMID 16617285.

- ↑ "Botulism associated with commercial carrot juice--Georgia and Florida, September 2006". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (40): 1098–9. 2006. PMID 17035929.

- ↑ Zhang S, Wang Y, Qiu S, Dong Y, Xu Y, Jiang D, Fu X, Zhang J, He J, Jia L, Wang L, Zhang C, Sun Y, Song H (2010). "Multilocus outbreak of foodborne botulism linked to contaminated sausage in Hebei province, China". Clin. Infect. Dis. 51 (3): 322–5. doi:10.1086/653945. PMID 20569065.

- ↑ McCrickard L, Marlow M, Self JL, Watkins LF, Chatham-Stephens K, Anderson J, Hand S, Taylor K, Hanson J, Patrick K, Luquez C, Dykes J, Kalb SR, Hoyt K, Barr JR, Crawford T, Chambers A, Douthit B, Cox R, Craig M, Spurzem J, Doherty J, Allswede M, Byers P, Dobbs T (2017). "Notes from the Field: Botulism Outbreak from Drinking Prison-Made Illicit Alcohol in a Federal Correctional Facility - Mississippi, June 2016". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65 (52): 1491–1492. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a8. PMID 28056003.

- ↑ McCarty CL, Angelo K, Beer KD, Cibulskas-White K, Quinn K, de Fijter S, Bokanyi R, St Germain E, Baransi K, Barlow K, Shafer G, Hanna L, Spindler K, Walz E, DiOrio M, Jackson BR, Luquez C, Mahon BE, Basler C, Curran K, Matanock A, Walsh K, Slifka KJ, Rao AK (2015). "Large Outbreak of Botulism Associated with a Church Potluck Meal--Ohio, 2015". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 64 (29): 802–3. PMID 26225479.