Pulmonary nodule

| Solitary pulmonary nodule | |

| |

|---|---|

| Malignant solitary pulmonary nodule: The patient is a 67 year old woman with a solitary pulmonary nodule on a recent chest x-ray. A retrospective review of prior chest x-rays suggests that this is nodule is of recent origin. This lesion was felt to be too peripheral for reliable bronchial wash findings. | |

| DiseasesDB | 29456 |

| MedlinePlus | 000071 |

| eMedicine | RADIO/782 |

| MeSH | D003074 |

Template:Search infobox For the WikiPatient page for this topic, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Synonyms and keywords: SPN, coin lesion

Overview

A solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) or coin lesion is a mass in the lung smaller than 3 centimeters in diameter. It can be an incidental finding found in up to 0.2% of chest X-rays[1] and around 1% of CT scans.[2]

The nodule most commonly represents a benign tumor such as a granuloma or hamartoma, but in around 20% of cases it represents a malignant cancer,[2] especially in older adults and smokers. Conversely, 10 to 20% of patients with lung cancer are diagnosed in this way.[2] Thus, the possibility of cancer needs to be excluded through further radiological studies and interventions, possibly including surgical resection. The prognosis depends on the underlying condition.

Definition

A solitary pulmonary nodulus needs to be separated from larger lung tumors, smaller infiltrates or masses with other accompanying characteristics. An often used formal radiological definition is the following: a single lesion in the lung completely surrounded by lung parenchyma (functional tissue) with a diameter less than 3 cm and without associated pneumonia, atelectasis (lung collaps) or lymphadenopathies (swollen lymph nodes).[3][4]

Differential diagnosis of causes of pulmonary nodule

Common Causes

Not every round spot on a radiological image is a coin lesion: it should not be confused with the projection of a structure of the chest wall or skin, such as a nipple, a healing rib fracture or electrocardiographic monitoring.

The most important cause to exclude is a form of lung cancer, including rare forms such as primary pulmonary lymphoma, carcinoid tumor and a solitary metastasis to the lung (common unrecognised primary tumor sites are melanomas, sarcomas or testicular cancer). Benign tumors in the lung include hamartomas and chondromas.

The most common benign coin lesion is a granuloma (inflammatory nodule), for example due to tuberculosis or a fungal infection. Other infectious causes include a pulmonary abscess, pneumonia (including Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) or rarely Nocardial infection or worm infection (such as dirofilariasis or dog heartworm infestation). Lung nodules can also occur in immune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis or Wegener's granulomatosis.

An SPN can be found to be an arteriovenous malformation, a hematoma or an infarction zone. It may also be caused by bronchial atresia, sequestration, an inhaled foreign body or pleural plaque.

Complete Differential Diagnosis

In alphabetical order [5]

- Amyloid

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Aneurysm of the pulmonary artery

- Benign tumors

- Breast Cancer

- Bronchial atresia

- Bronchial carcinomas

- Bronchogenic cyst

- Cancers

- Chondroma

- Endometriosis

- Fungal infections

- Gastric Cancer

- Granulomas

- Hamartoma

- Hemangioma

- Hypernephroma

- Hystiocytosis X

- Lipoid pneumonia

- Localized pleural effusion

- Localized scar

- Lymphoma

- Metastases

- Mucoid impaction

- Multiple Myeloma

- Neurogenic tumor

- Nocardia

- Parasites

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary infarction

- Pulmonary sequestration

- Prostate Cancer

- Rheumatoid nodule

- Sarcoma

- Seminoma

- Thyroid Cancer

- Tuberculosis

- Varicose pulmonary vein

Radiological features

Several features help to distinguish benign conditions from possible lung cancer. The first parameter is the size of the lesion: the smaller, the less risk for malignant cancer.[4] Benign causes tend to have a well defined border, whereas lobulated lesions or those with an irregular margin extending into the neighbouring tissue tend to be malignant.[4]

If there is a central cavity, then a thin wall points to a benign cause whereas a thick wall is associated with malignancy (especially 4mm or less versus 16mm or more).[4] In lung cancer, cavitation can represent central tumor necrosis (tissue death) or secondary abces formation. If the walls of an airway are visible (air bronchogram), bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is a possibility.

An SPN often contains calcifications. Certain patterns of calcification are reassuring, such as the popcorn-like appearance of hamartoma.[1] An SPN with a density below 15 Hounsfield units on computed tomography tends to be benign, whereas malignant tumors often measure more than 20 Hounsfield units. Fatty tissue inside hamartomas will have a strongly negative value on the Hounsfield scale.

The growth velocity of a lesion is also informative: very fast or very slow growing tumors are rarely malignant, in contrary to inflammatory or congenital conditions.[6] It is therefore important to retrieve previous imaging studies to see if a lesion was presented and how fast its volume is increasing. This is more difficult for nodules smaller than 1 centimeter. Moreover, the predictive value of stable lesion over a period of 2 years has been found to be rather low and unreliable.[6]

-

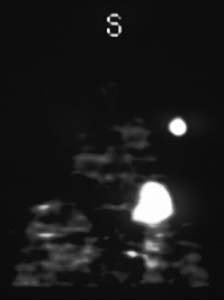

Malignant solitary pulmonary nodule: The patient is a 67 year old woman with a solitary pulmonary nodule on a recent chest x-ray. A retrospective review of prior chest x-rays suggests that this is nodule is of recent origin. This lesion was felt to be too peripheral for reliable bronchial wash findings. Concern over potential sampling error associated with needle biopsy prompted a referral for PET imaging to rule out a malignant process.

-

After a 4 hour fast, the patient was injected with 10 mCi of 18-FDG IV and after allowing one hour for localization, transmission and emission PET data were acquired. A hypermetabolic focus can be seen in the left upper lobe corresponding to the chest x-ray abnormality. No other abnormalities are seen. The hypermetabolic nodule suggests a malignant process without metastasis. Lesions with only slight tracer uptake can be evaluated quantitatively for significance. A significant uptake value (SUV) can be calculated by dividing the mean activity in the suspicious area (mCi/ml) by the injected dose (mCi) per kilograms of body weight. Using a (SUV) of 2.5 or greater to define a malignancy, the sensitivity and specificity of 18-FDG-PET for detecting cancer in solitary pulmonary nodules greater than 1.2 cm approaches 90% with a nearly 100% specificity (1). False positives have included infectious etiologies, and sarcoid.

-

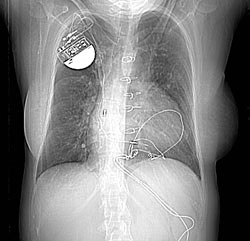

Chest x-ray: A 32 year old woman. 1. Two pulmonary arteriovenous malformations consistent with the nodules seen on the recent chest film. There is breathing artifact on several of the images and other tiny AVMs cannot be excluded. 2. Cardiomegaly with right atrial and left atrial enlargement and hepatic congestion.

-

Thorax CT

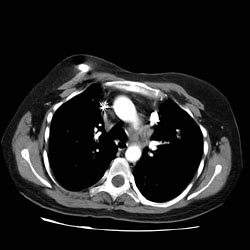

Halo Sign

- The halo sign refers to a zone of ground-glass attenuation surrounding a pulmonary nodule or mass on CT images.

- The presence of a halo of ground-glass opacity or ground-glass attenuation is usually associated with hemorrhagic nodules.

- In severely neutropenic patients, the halo sign is highly suggestive of infection by an angioinvasive fungus, most commonly Aspergillus.

- Vascular invasion by this fungus results in thrombosis of small- to medium-sized vessels, which causes ischemic necrosis.

- At pathologic examination, the nodules represent foci of infarction, and the halo of ground-glass attenuation results from alveolar hemorrhage.

- Although it is less common, the halo sign may also be observed in nonhemorrhagic nodules, in which case either tumor cells or inflammatory infiltrate account for the halo of ground-glass attenuation.

Patient features

Several patient factors may influence the likelihood of a benign versus a malignant condition: these include previous exposure to smoke or other carcinogens such as asbestos, and previously diagnosed cancer or respiratory infections. A patient with airway symptoms, especially coughing up blood (hemoptysis), is more likely to have cancer compared to a patient with no respiratory symptoms.

Treatment

Recommendations for Follow-up and Management of Nodules <8 mm Detected Incidentally at Non-screening CT

| Nodule Size (mm) | Low risk patients | High risk patients |

|---|---|---|

| Less than or equal to 4 | No follow-up needed. | Follow-up at 12 months. If no change, no further imaging needed. |

| >4 - 6 | Follow-up at 12 months. If no change, no further imaging needed. | Initial follow-up CT at 6 -12 months and then at 18 - 24 months if no change. |

| >6 - 8 | Initial follow-up CT at 6 -12 months and then at 18 - 24 months if no change. | Initial follow-up CT at 3 - 6 months and then at 9 -12 and 24 months if no change. |

| >8 | Follow-up CTs at around 3, 9, and 24 months. Dynamic contrast enhanced CT, PET, and/or biopsy | Same at for low risk patients |

Note: Newly detected indeterminate nodule in persons 35 years of age or older.[7]

- Low risk patients: Minimal or absent history of smoking and of other known risk factors.

- High risk patients: History of smoking or of other known risk factors.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH (2003). "Clinical practice. The solitary pulmonary nodule". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (25): 2535–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp012290. PMID 12815140. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Alzahouri K, Velten M, Arveux P, Woronoff-Lemsi MC, Jolly D, Guillemin F (2008). "Management of SPN in France. Pathways for definitive diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodule: a multicentre study in 18 French districts". BMC Cancer. 8: 93. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-8-93. PMC 2373300. PMID 18402653.

- ↑ Tan BB, Flaherty KR, Kazerooni EA, Iannettoni MD (2003). "The solitary pulmonary nodule". Chest. 123 (1 Suppl): 89S–96S. PMID 12527568. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Winer-Muram HT (2006). "The solitary pulmonary nodule". Radiology. 239 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1148/radiol.2391050343. PMID 16567482. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Sailer, Christian, Wasner, Susanne. Differential Diagnosis Pocket. Hermosa Beach, CA: Borm Bruckmeir Publishing LLC, 2002: 306-307 ISBN 1591032016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Roggli VL (2000). "Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions". Radiographics. 20 (1): 43–58. PMID 10682770.

- ↑ Heber MacMahon, John H. M. Austin, Gordon Gamsu, Christian J. Herold, James R. Jett, David P. Naidich, Edward F. Patz, Jr, and Stephen J. Swensen. Guidelines for Management of Small Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Scans: A Statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2005 237: 395-400.