Lateral medullary syndrome

| Lateral medullary syndrome | |

| |

|---|---|

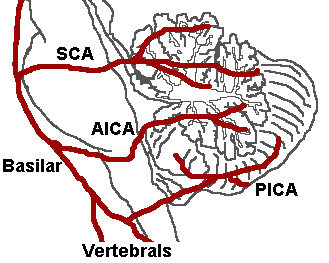

| The three major arteries of the cerebellum: the SCA, AICA, and PICA. (Posterior inferior cerebellar artery is PICA.) | |

| ICD-10 | G46.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 10449 |

| eMedicine | emerg/834 |

| MeSH | D014854 |

Lateral medullary syndrome (also called Wallenberg's syndrome and posterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome) is a neurological condition caused by a stroke in the vertebral or posterior inferior cerebellar artery of the brain stem. Symptoms include difficulties with swallowing, hoarseness, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, rapid involuntary movements of the eyes (nystagmus), and problems with balance and gait coordination. Some individuals will experience a lack of pain and temperature sensation on only one side of the face, or a pattern of symptoms on opposite sides of the body – such as paralysis or numbness in the right side of the face, with weak or numb limbs on the left side. Uncontrollable hiccups may also occur, and some individuals will lose their sense of taste on one side of the tongue, while preserving taste sensations on the other side. Some people with Wallenberg’s syndrome report that the world seems to be tilted in an unsettling way, which makes it difficult to keep their balance when they walk.

Cause

It is the clinical manifestation resulting from occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or one of its branches or of the vertebral artery, in which the lateral part of the medulla oblongata infarcts, resulting in a typical pattern.

Clinical features

Lateral medullary syndrome presents with the following symptoms:

| Dysfunction | Effects |

| lateral spinothalamic tract | contralateral deficits in pain and temperature sensation from body |

| spinal trigeminal nucleus | ipsilateral loss of pain and temperature sensation from face |

| nucleus ambiguus (which affects vagus X and glossopharyngeal nerves IX) | dysphagia, hoarseness, diminished gag reflex |

| vestibular system | vertigo, diplopia, nystagmus, vomiting |

| descending sympathetic fibers | ipsilateral Horner's syndrome |

| central tegmental tract | palatal myoclonus |

An affected person may present with ataxia on the side of lesion. Hiccups are another common sign.

Presentation

This syndrome is characterized by sensory deficits affecting the trunk and extremities on the opposite side of the infarct and sensory and motor deficits affecting the face and cranial nerves on the same side with the infarct. Other clinical symptoms and findings are ataxia, facial pain, vertigo, nystagmus, Horner's syndrome, diplopia and dysphagia. The cause of this syndrome is usually the occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) at its origin.

The affected persons have difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) resulting from involvement of the nucleus ambiguus, and slurred speech (dysphonia, dysarthria). Damage to the spinal trigeminal nucleus causes absence of pain on the ipsilateral side of the face, as well as an absent corneal reflex.

The spinothalamic tract is damaged, resulting in loss of pain and temperature sensation to the opposite side of the body. The damage to the cerebellum or the inferior cerebellar peduncle can cause ataxia.

Nystagmus and vertigo, which may result in falling, caused from involvement of the region of Deiters' nucleus and other vestibular nuclei.

Onset is usually acute with severe vertigo.

Treatment

Treatment for lateral medullary syndrome is symptomatic. A feeding tube may be necessary if swallowing is very difficult. Speech/swallowing therapy may be beneficial. In some cases, medication may be used to reduce or eliminate pain. Some doctors report that the anti-epileptic drug gabapentin appears to be an effective medication for individuals with chronic pain.

Prognosis

The outlook for someone with lateral medullary syndrome depends upon the size and location of the area of the brain stem damaged by the stroke. Some individuals may see a decrease in their symptoms within weeks or months. Others may be left with significant neurological disabilities for years after the initial symptoms appeared.

History

This syndrome was first described in 1808 by Gaspard Viesseux,[1]. First descriptions by Wallenberg were in 1895 (clinical) and 1901 (autopsy findings).

See Also

References

External links

Template:Diseases of the nervous system Template:Lesions of spinal cord and brainstem