Inguinal hernia overview: Difference between revisions

Farima Kahe (talk | contribs) |

Farima Kahe (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

===Other Diagnostic Studies=== | ===Other Diagnostic Studies=== | ||

There are no other diagnostic studies associated with inguinal hernia. | |||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

Revision as of 17:16, 23 January 2018

|

Inguinal hernia Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Inguinal hernia overview On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Inguinal hernia overview |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Inguinal hernia overview |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Inguinal hernias (Template:IPAEng) are protrusions of abdominal cavity contents through the inguinal canal. They are very common and their repair is one of the most frequently performed surgical operations.

There are two types of inguinal hernia, direct and indirect. Direct inguinal hernias occur when abdominal contents herniate through a weak point in the fascia of the abdominal wall and into the inguinal canal. Indirect inguinal hernias occur when abdominal contents protrude through the deep inguinal ring; this is ultimately caused by failure of embryonic closure of the internal inguinal ring.

Historical Perspective

Reinforcement of the anterior wall of the inguinal canal and tightening of the external inguinal ring was first discovered by Stromayr in 1559. In 1871, new use of carbolized catgut ligature was developed by Marcy to treat inguinal hernia. Twisted and suture-transfixed the peritoneal sac in the lateral muscles through the external ring was developed by Kocher to treat inguinal hernia.

Classification

Reinforcement of the anterior wall of the inguinal canal and tightening of the external inguinal ring was first discovered by Stromayr in 1559. In 1871, new use of carbolized catgut ligature was developed by Marcy to treat inguinal hernia. Twisted and suture-transfixed the peritoneal sac in the lateral muscles through the external ring was developed by Kocher to treat inguinal hernia.

Pathophysiology

Directed inguinal hernia is caused by protrusion through Hesselbach triangle, passes medial to inferior epigastric vessels. Indirected inguinal hernia is caused by passes through internal inguinal ring, traverses inguinal canal to external ring, and may extend into scrotum in males and labia major in females.

Causes

Common causes of inguinal hernia include combination of increased pressure within the abdomen and a pre-existing weak spot in the abdominal wall, chronic coughing or sneezing, heavy lifting such as weightlifting, abdominal wall defects and advanced age.

Differentiating Inguinal hernia overview from Other Diseases

Inguinal hernia must be differentiated testicular torsion, epididymitis, hydrocele, varicocele, spermatocele, epididymal cyst and testicular tumor.

Epidemiology and Demographics

The incidence of inguinal hernia is approximately 110 per 100,000 individuals in years aged 16-24 years to 2000 per 100,000 person years aged 75 years or above in men.*The prevalence of inguinal hernia is approximately 1700 per 100,000 individuals for all ages and 4000 per 100,000 for those aged over 45 yearsworldwide. The incidence of inguinal hernia increases with age; the median age at diagnosis is 40-59 years. Male are more commonly affected by inguinal hernia than female. The male to female ratio is approximately 9 to 1.

Risk Factors

Common risk factors in the development of inguinal hernia include history of hernia or prior hernia repair, older age, male gender, obesity.

Screening

There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for inguinal hernia.

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

The symptoms of inguinal hernia usually develop in the 4th decade of life, and start with symptoms such as bulging, heaviness, burning, or aching in the groin.

Complications

Common complications of inguinal hernia include bowel obstruction, bowel strangulation and incaeceration.

Prognosis

Prognosis is generally good, and mortalilty is very rare.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of inguinal hernia is based on clinical examination and symptoms.

History and Symptoms

Symptoms of inguinal hernia include nausea and vomiting, heaviness or dull discomfort in the groin, especially when straining, lifting, coughing, or exercising that improves when resting.

Physical Examination

Patients with inguinal hernia usually appear good. Physical examination of patients with inguinal hernia is usually remarkable for bulge in the groin, painless scrotal mass and palpable abdominal mass may be present.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings is usually normal among patients with inguinal hernia.

Imaging Findings

-

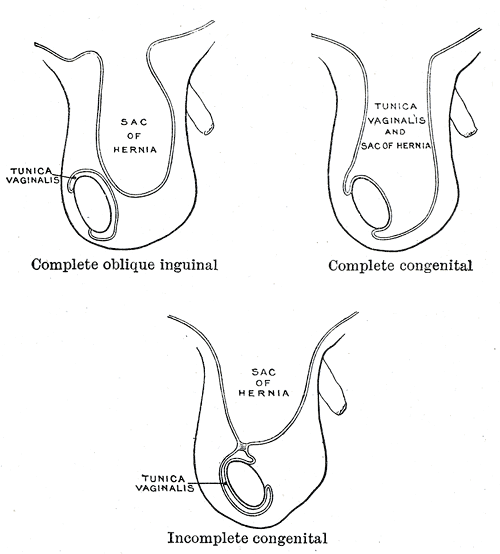

Different types of inguinal hernias.

-

Inguinal fossae

Other Diagnostic Studies

There are no other diagnostic studies associated with inguinal hernia.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Surgery

The inability to "reduce" the bulge back into the abdomen usually means the hernia is "incarcerated," often necessitating emergency surgery. Recent data questions the routine elective repair of all inguinal hernias. Some studies indicate that inguinal hernias can be left alone with no greater risk than prompt elective treatment. Nevertheless, the bias remains toward surgical repair. Provided there are no serious co-existing medical problems, patients are advised to get the hernia repaired surgically at the earliest convenience after a diagnosis is made. Emergency surgery for complications such as incarceration and strangulation carry much higher risk than planned, "elective" procedures.