Chickenpox pathophysiology

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aravind Reddy Kothagadi M.B.B.S[2]

|

Chickenpox Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Chickenpox pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Chickenpox pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Chickenpox pathophysiology |

Overview

Chickenpox is a highly contagious disease contracted by the inhalation of aerosolized nasopharyngeal secretions droplets or through direct contact with the vesicles from an infected host. It takes from 10 to 21 days after exposure to a person with chickenpox or shingles for someone to develop chickenpox. Viral proliferation occurs in regional lymph nodes of the upper respiratory tract leading to viremia. Viremia is characterized by diffuse viral invasion of capillary endothelial cells and the epidermis. VZV infection of cells of the malpighian layer produces both intercellular and intracellular edema, resulting in the characteristic vesicle.

Pathophysiology

Chickenpox is contracted by the inhalation of aerosolized nasopharyngeal secretions droplets from an infected host. The highly contagious nature of VZV explains the epidemics of chickenpox that spread through schools as one child who is infected quickly spreads the virus to many classmates. High viral titers are found in the vesicles of chickenpox; hence, the viral transmission may also occur through direct contact with these vesicles and the risk is lower comparatively.

Transmission

- The virus spreads easily from people with chickenpox to others who have never had the disease or received the chickenpox vaccine. The virus spreads in the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It can also be spread by touching or breathing in the virus particles that come from chickenpox blisters. [1]

- Chickenpox can also be spread from people with shingles. Varicella-zoster virus also causes shingles. A person with shingles can spread the virus to others who have never had chickenpox or received the chickenpox vaccine. In these cases, the exposed person might develop chickenpox.

- Transmission of the disease occurs 1-2 days prior to the development of the rash and continues until all their chickenpox blisters have formed scabs.

- If a person vaccinated for chickenpox gets the disease, they can still spread it to others.

- In the majority, infection with chickenpox provides lifetime immunity. However, for a few people re-infection with chickenpox may occur, although this is not common.

- Nosocomial transmission of Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is well-recognized and can be life threatening to certain groups of patients. Reports of nosocomial transmission are relatively uncommon in the United States since introduction of varicella vaccine. [2]

Incubation Period

- The incubation period of chickenpox is typically from 14 to 16 days, however the interval may vary from 10 to 21 days. [3]

- The infectivity period is regarded to last from 48 hours before the appearance of the rash till the crusts appear.

Dissemination

- After initial inhalation of contaminated aerosolized droplets, the virus infects the conjunctivae or the mucosae of the upper respiratory tract. Viral proliferation occurs in regional lymph nodes of the upper respiratory tract 2-4 days after initial infection and is followed by primary viremia on postinfection days 4-6.

Pathogenesis

- A second round of viral replication occurs in the body's internal organs, most notably the liver and the spleen, followed by a secondary viremia 14-16 days postinfection. This secondary viremia is characterized by diffuse viral invasion of capillary endothelial cells and the epidermis. VZV infection of cells of the malpighian layer produces both intercellular and intracellular edema, resulting in the characteristic vesicle.

- Exposure to VZV in a healthy child initiates the production of host immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies; IgG antibodies persist for life and confer immunity.

- Cell-mediated immune responses are also important in limiting the scope and the duration of primary varicella infection. After primary infection, VZV is hypothesized to spread from mucosal and epidermal lesions to local sensory nerves. VZV then remains latent in the dorsal ganglion cells of the sensory nerves.

- Reactivation of VZV results in the clinically distinct syndrome of herpes zoster (shingles).

Genetics

- There is no genetic predisposition associated with the disease chickenpox. However, regarding varicella vaccination, similarities in siblings' response to varicella vaccine are supportive of the hypothesis that genetic factors play a role in the antibody response to the varicella vaccine. [4]

Associated Conditions

There are no associated conditions with chickenpox.

Gross Pathology

- There area no gross pathological findings findings observed in chickenpox. In varicella pneumonia, calcifications are observed in the lungs. [5]

Microscopic Pathology

-

Varicella virus grown in a tissue culture; magnified 500X.

-

Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a Varicella (Chickenpox) Virus. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Various viruses from the Herpesviridae family seen using an electron micrograph. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

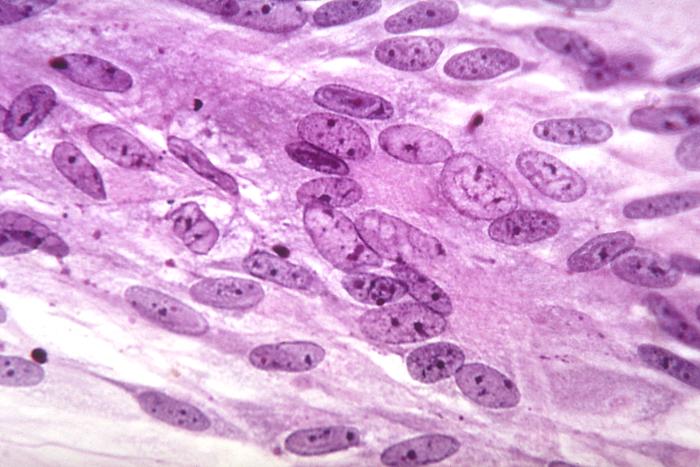

photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes which you’d find in a human skin tissue specimen that included a chickenpox, or varicella zoster virus lesion (500x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (50x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (50x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (500x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (1200x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

-

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (1200x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]

References

- ↑ Straus SE, Ostrove JM, Inchauspé G, Felser JM, Freifeld A, Croen KD; et al. (1988). "NIH conference. Varicella-zoster virus infections. Biology, natural history, treatment, and prevention". Ann Intern Med. 108 (2): 221–37. PMID 2829675.

- ↑ Leclair JM, Zaia JA, Levin MJ, Congdon RG, Goldmann DA (1980). "Airborne transmission of chickenpox in a hospital". N Engl J Med. 302 (8): 450–3. doi:10.1056/NEJM198002213020807. PMID 7351951.

- ↑ Heininger U, Seward JF (2006). "Varicella". Lancet. 368 (9544): 1365–76. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69561-5. PMID 17046469.

- ↑ Klein NP, Fireman B, Enright A, Ray P, Black S, Dekker CL (2007). "A role for genetics in the immune response to the varicella vaccine". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (4): 300–5. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000257454.74513.07. PMID 17414391.

- ↑ Raider L (1971). "Calcification in chickenpox pneumonia". Chest. 60 (5): 504–7. PMID 5119892.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

![Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a Varicella (Chickenpox) Virus. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/f/fa/VZV14.jpeg)

![Various viruses from the Herpesviridae family seen using an electron micrograph. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/7/76/VZV13.jpeg)

![photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes which you’d find in a human skin tissue specimen that included a chickenpox, or varicella zoster virus lesion (500x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/e/e2/VZV09.jpeg)

![Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (50x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/f/fa/VZV08.jpeg)

![Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (50x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/3/3d/VZV07.jpeg)

![Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (500x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/3/3d/VZV06.jpeg)

![Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (1200x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/1/14/VZV05.jpeg)

![Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained photomicrograph reveals some of the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in a human skin tissue specimen that included a varicella zoster virus lesion (1200x mag). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [6]](/images/8/84/VZV04.jpeg)