Congestive heart failure chronic pharmacotherapy

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1], Assistant editor-in-chief Rim Halaby

Overview

There are several goals in the chronic management of systolic heart failure. The management of diastolic heart failure is discussed elsewhere. The first goal is to treat the patient's symptoms of heart failure and to improve the patient's exercise tolerance and quality of life. The use of diuretics and regular assessment of the patient's weight helps in avoiding excess body fluids that are associated with dyspnea and orthopnea. Another goal of the chronic treatment of heart failure is to decrease the rate of hospitalization and mortality. To cheat the second goal, patients with chronic heart failure should be administered an ACE inhibitor (or ARB if they are ACE intolerant) and a beta blocker. If the patient remains symptomatic, additional therapy may be advised.

Chronic Pharmacotherapy

Treatment Goals

Improvement of symptoms:

Decreased Mortality:

- ACE inhibitors

- ARBs

- Beta blockers

- Diuretics (in meta-analyses) [1]

- Nitrates and hydralazine

- Spironolactone[2]

A General Strategy in the Chronic Treatment of Heart Fialure

Diuresis: First step in the management of heart failure

Begin by rapidly improving the symptoms of heart failure (within hours to days) by the use of diuretics. Diuretics reduce excess volume that accumulates with heart failure and decrease pulmonary edema that causes symptoms of dyspnea and orthopnea[3]. Lasix 20 to 40 mg PO daily is a conventional starting dose, but in some patients, torsemide may have better and more predictable absorption. Once a day dosing of a givne diuretic is preferred to twice a day dosing at a lower dose. A rise in BUN and Cr may reflect a reduction in renal perfusion, and further diuresis should only be undertaken with careful monitoring. The patient should weigh themselves each morning at the same time on the same scale, and the diuretic dosing should be adjusted to maintain a constant weight.

- Simultaneous with number 1

- Treat the underlying cause of heart failure such as ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and valvular heart disease.

- Treat other non cardiac diseases that might contribute to the symptoms of heart failure such as diabetes and hyperthyroidism[4].

- Treat with a low salt diet[5]

- Follow the patient's weight to check for fluid overload

- Treat with vaccines for influenza and pneumococcus [6].

ACE Inhibition and Angiotensin Receptor Blockade: Second step in the management of heart failure

After diuretics are started or at the same time you can begin the use of an ACE inhibitors [7]. An example would be to start lisinopril 5 mg Q day. Every one to two weeks, the dose would be escalated to achieve a target dose of 15 to 20 mg Q day. ACE inhibitors are initiated before a beta blocker because they achieved their hemodynamic effects more rapidly, and they are less likely to cause a decline in hemodynamic function. If an ACE inhibitor is not tolerated, then an angiotensin receptor blocker ARB is started. Although there is some data to suggest that aspirin blunts the hemodynamic effect of ACE inhibitors, there is no data to suggest that aspirin reduces the clinical efficacy of ACE inhibitors in heart failure patients. Aspirin should be administered to patients with ischemic heart disease, but not to patients without it.

If a patient cannot tolerate a an ACE inhibitor (develops a cough), then an Angiotensin II receptor blocker can be administered. The benefit from this approach was demonstrated for candesartan in the CHARM trial [8].

Beta blockers: Third step in the management of heart failure

Once you have achieved a stable dose of a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor, then one of the three beta blockers that have been associated with improved survival (carvedilol, metoprolol succinate or bisoprolol) can be added and the dose titrated based upon the patient's tolerance. You should avoid beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (pindolol or acebutolol). It should be noted that the 35% reduction in one year mortality observed in meta-analyses of beta-blockers in heart failure was when these drugs were added to ACE inhibitors[9]. There are no direct comparisons of the various beta-blockers, but some data does suggest that carvedilol may improve LVEF more than the others, but it may not be as well tolerated due to its vasodilatory properties. If the patient has been over diuresed, they may not tolerate the addition of a beta blocker.

- Relative contraindications to beta-blocker administration include the following:

- Asthma or bronchospasm

- Hypotension resulting in poor end organ perfusion or symptoms

- Bradycardia or heart block (first degree heart block with a PR interval > 0.24, second degree heart block, third degree heart block

- Peripheral arterial disease with limb ischemia at rest

- Moderate or greater peripheral edema

- Recent intravenous inotropic therapy

Given the potential for hemodynamic complications, the initiation of beta-blockers is best undertaken by an individual or center specializing in heart failure management. The patient should be aware of potential side effects, and should be aware that it may take one to three months for the beta-blockers to improve heart failure symptoms. THerapy is initiated with very low doses, and the dose of the beta-blocker should be doubled every two weeks until the target dose is achieved or symptoms prevent further dose escalation.

- Carvedilol: Initial dose 3.125 mg twice daily, target dose 25 to 50 mg twice daily

- Metoprolol succinate: Initial dose 12.5 mg daily, target dose 200 mg daily

- Bisoprolol: Initial dose 1.25 mg daily, target dose 5 to 10 mg daily

Weight gain or peripheral edema that is not responsive to diuresis may require a reduction in the dose of beta-blockers.

Aldosterone antagonism: Fourth step in the management of heart failure

An aldosterone antagonist can be added to the regimen of 'select' patients. These selected patients include:

- Class II heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%

- Class III/IV heart failure and a LVEF <35%

- Post ST segment elevation MI and a LVEF < 40% who have either symptomatic heart failure or diabetes.

- The Serum potassium must be under 5.0 meq/li and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) should be > 30 cc per minute

A requirement for aldosterone antagonist is that the patient's renal function and potassium can be carefully monitored. Eplerenone has fewer endocrine side effects (1%) than spironolactone (10%), but is more costly. A reasonable strategy is to initiate therapy with spironolactone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily, and then switch to eplerenone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily if endocrine side effects develop.

Risk factors for the development of hyperkalemia on an aldosterone antagonist

- Triple therapy with an ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker makes this combination a contraindication

- Higher doses of either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

- Hyperkalemia prior to initiation of spironolactone

- Comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic renal insufficiency

- Higher NYHA heart failure class

- Concomitant administration of beta blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs )NSAIDs) or potassium supplements

- A daily dose of Spironolactone greater than 50 mg

The combination of hydralazine and a nitrate: Fifth step in the management of heart failure

The combination of hydralazine and a nitrate (particularly among black patients) can be added if the patient continues to have symptoms on an ACE inhibitor and a beta blocker.

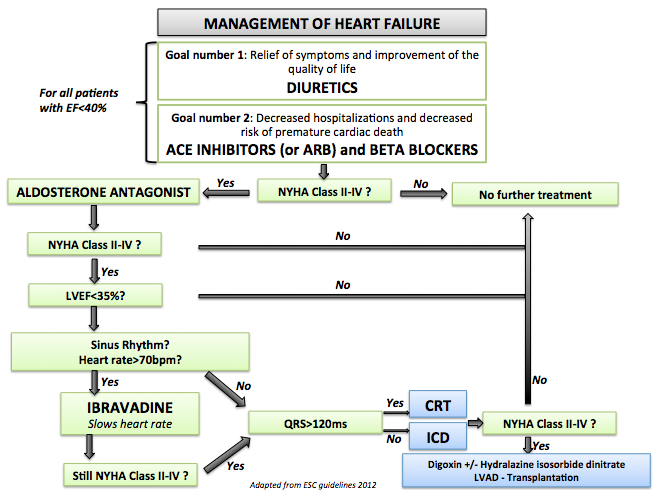

- Shown below is an image that summarizes the steps in the chronic management of patients with heart failure.

References

- ↑ Faris R, Flather MD, Purcell H, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ (2006). "Diuretics for heart failure". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) (1): CD003838. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003838.pub2. PMID 16437464. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ Davies MK, Gibbs CR, Lip GY (2000). "ABC of heart failure. Management: diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and nitrates". BMJ. 320 (7232): 428–31. PMC 1117548. PMID 10669450.

- ↑ Michael Felker G (2010). "Diuretic management in heart failure". Congest Heart Fail. 16 Suppl 1: S68–72. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00172.x. PMID 20653715.

- ↑ DeGroot WJ, Leonard JJ (1970). "Hyperthyroidism as a high cardiac output state". Am Heart J. 79 (2): 265–75. PMID 4903771.

- ↑ Evangelista LS, Shinnick MA (2008). "What do we know about adherence and self-care?". J Cardiovasc Nurs. 23 (3): 250–7. doi:10.1097/01.JCN.0000317428.98844.4d. PMC 2880251. PMID 18437067.

- ↑ Martins Wde A, Ribeiro MD, Oliveira LB, Barros Lda S, Jorge AC, Santos CM; et al. (2011). "Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in heart failure: a little applied recommendation". Arq Bras Cardiol. 96 (3): 240–5. PMID 21271169.

- ↑ Shiokawa Y (1975). "Proceedings: Streptococcus surveys in Ryukyu Islands, Japan". Jpn Circ J. 39 (2): 168–71. PMID 1117548.

- ↑ Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K (2003). "Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial". Lancet. 362 (9386): 772–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. PMID 13678870. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Brophy JM, Joseph L, Rouleau JL (2001). "Beta-blockers in congestive heart failure. A Bayesian meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (7): 550–60. PMID 11281737. Retrieved 2013-04-28. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)