Hydrogen bond

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

A hydrogen bond is a special type of dipole-dipole force that exists between an electronegative atom and a hydrogen atom bonded to another electronegative atom. This type of force always involves a hydrogen atom and the energy of this attraction is close to that of weak covalent bonds (155 kJ/mol), thus the name - Hydrogen Bonding. These attractions can occur between molecules (intermolecularly), or within different parts of a single molecule (intramolecularly).[2] The hydrogen bond is a very strong fixed dipole-dipole van der Waals-Keesom force, but weaker than covalent, ionic and metallic bonds. The hydrogen bond is somewhere between a covalent bond and an electrostatic intermolecular attraction.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonding is responsible for the high boiling point of water (100 °C). This is because of the strong hydrogen bond, as opposed to other group 16 hydrides. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding is partly responsible for the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins and nucleic acids.

Bonding

A hydrogen atom attached to a relatively electronegative atom is a hydrogen bond donor. This electronegative atom is usually fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen. An electronegative atom such as fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen is a hydrogen bond acceptor, regardless of whether it is bonded to a hydrogen atom or not. An example of a hydrogen bond donor is ethanol, which has a hydrogen bonded to oxygen; an example of a hydrogen bond acceptor which does not have a hydrogen atom bonded to it is the oxygen atom on diethyl ether.

Carbon can also participate in hydrogen bonding, especially when the carbon atom is bound to several electronegative atoms, as is the case in chloroform, CHCl3. The electronegative atom attracts the electron cloud from around the hydrogen nucleus and, by decentralizing the cloud, leaves the atom with a positive partial charge. Because of the small size of hydrogen relative to other atoms and molecules, the resulting charge, though only partial, nevertheless represents a large charge density. A hydrogen bond results when this strong positive charge density attracts a lone pair of electrons on another heteroatom, which becomes the hydrogen-bond acceptor.

The hydrogen bond is often described as an electrostatic dipole-dipole interaction. However, it also has some features of covalent bonding: it is directional, strong, produces interatomic distances shorter than sum of van der Waals radii, and usually involves a limited number of interaction partners, which can be interpreted as a kind of valence. These covalent features are more significant when acceptors bind hydrogens from more electronegative donors.

The partially covalent nature of a hydrogen bond raises the questions: "To which molecule or atom does the hydrogen nucleus belong?" and "Which should be labeled 'donor' and which 'acceptor'?" Usually, this is easy to determine simply based on interatomic distances in the X-H...Y system: X-H distance is typically ~1.1 Å, whereas H...Y distance is ~ 1.6 to 2.0 Å. Liquids that display hydrogen bonding are called associated liquids.

Hydrogen bonds can vary in strength from very weak (1-2 kJ mol−1) to extremely strong (>155 kJ mol−1), as in the ion HF2−.[3] Typical values include:

- F—H...:F (155 kJ/mol or 40 kcal/mol)

- O—H...:N (29 kJ/mol or 6.9 kcal/mol)

- O—H...:O (21 kJ/mol or 5.0 kcal/mol)

- N—H...:N (13 kJ/mol or 3.1 kcal/mol)

- N—H...:O (8 kJ/mol or 1.9 kcal/mol)

- HO—H...:OH3+ (18 kJ/mol[4] or 4.3 kcal/mol) {Data obtained using molecular dynamics as detailed in the reference and should be compared to 7.9 kJ/mol for bulk waters, obtained using the same molecular dynamics.}

The length of hydrogen bonds depends on bond strength, temperature, and pressure. The bond strength itself is dependent on temperature, pressure, bond angle, and environment (usually characterized by local dielectric constant). The typical length of a hydrogen bond in water is 1.97 Å (197 pm).

Hydrogen bonds in water

The most ubiquitous, and perhaps simplest, example of a hydrogen bond is found between water molecules. In a discrete water molecule, water has two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Two molecules of water can form a hydrogen bond between them; the simplest case, when only two molecules are present, is called the water dimer and is often used as a model system. When more molecules are present, as is the case in liquid water, more bonds are possible because the oxygen of one water molecule has two lone pairs of electrons, each of which can form a hydrogen bond with hydrogens on two other water molecules. This can repeat so that every water molecule is H-bonded with up to four other molecules, as shown in the figure (two through its two lone pairs, and two through its two hydrogen atoms.)

Liquid water's high boiling point is due to the high number of hydrogen bonds each molecule can have relative to its low molecular mass, not to mention the great strength of these hydrogen bonds. Realistically the water molecule has a very high boiling point, melting point and viscosity compared to other similar substances not conjoined by hydrogen bonds. The reasoning for these attributes is the inability to, or the difficulty in, breaking these bonds. Water is unique because its oxygen atom has two lone pairs and two hydrogen atoms, meaning that the total number of bonds of a water molecule is up to four. For example, hydrogen fluoride—which has three lone pairs on the F atom but only one H atom—can have a total of only two bonds (ammonia has the opposite problem: three hydrogen atoms but only one lone pair).

- H-F...H-F...H-F

The exact number of hydrogen bonds in which a molecule in liquid water participates fluctuates with time and depends on the temperature. From TIP4P liquid water simulations at 25 °C, it was estimated that each water molecule participates in an average of 3.59 hydrogen bonds. At 100 °C, this number decreases to 3.24 due to the increased molecular motion and decreased density, while at 0 °C, the average number of hydrogen bonds increases to 3.69.[5] A more recent study found a much smaller number of hydrogen bonds: 2.357 at 25 °C.[6] The differences may be due to the use of a different method for defining and counting the hydrogen bonds.

Where the bond strengths are more equivalent, one might instead find the atoms of two interacting water molecules partitioned into two polyatomic ions of opposite charge, specifically hydroxide (OH−) and hydronium (H3O+). (Hydronium ions are also known as 'hydroxonium' ions.)

- H-O− H3O+

Indeed, in pure water under conditions of standard temperature and pressure, this latter formulation is applicable only rarely; on average about one in every 5.5 × 108 molecules gives up a proton to another water molecule, in accordance with the value of the dissociation constant for water under such conditions. It is a crucial part of the uniqueness of water.

Bifurcated and over-coordinated hydrogen bonds in water

It can be that a single hydrogen atom participates in two hydrogen bonds, rather than one. This type of bonding is called "bifurcated". It was suggested that a bifurcated hydrogen atom is an essential step in water reorientation;[7] however, the case of an oxygen lone pair participating in more than two hydrogens bonds is rarely given attention in the scientific literature.

Hydrogen bonds in DNA and proteins

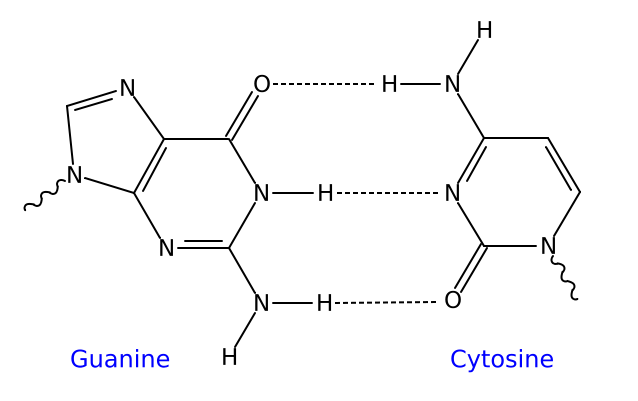

Hydrogen bonding also plays an important role in determining the three-dimensional structures adopted by proteins and nucleic bases. In these macromolecules, bonding between parts of the same macromolecule cause it to fold into a specific shape, which helps determine the molecule's physiological or biochemical role. The double helical structure of DNA, for example, is due largely to hydrogen bonding between the base pairs, which link one complementary strand to the other and enable replication.

In proteins, hydrogen bonds form between the backbone oxygens and amide hydrogens. When the spacing of the amino acid residues participating in a hydrogen bond occurs regularly between positions i and i + 4, an alpha helix is formed. When the spacing is less, between positions i and i + 3, then a 310 helix is formed. When two strands are joined by hydrogen bonds involving alternating residues on each participating strand, a beta sheet is formed. Hydrogen bonds also play a part in forming the tertiary structure of protein through interaction of R-groups.(See also protein folding).

A special case of intramolecular hydrogen bonds within proteins, poorly shielded from water attack and hence promoting their own dehydration, are called dehydrons.

Symmetric hydrogen bond

A symmetric hydrogen bond is a special type of hydrogen bond in which the proton is spaced exactly halfway between two identical atoms. The strength of the bond to each of those atoms is equal. It is an example of a 3-center 4-electron bond. This type of bond is much stronger than "normal" hydrogen bonds, in fact, its strength is comparable to a covalent bond. It is seen in ice at high pressure, and also in the solid phase of many anhydrous acids such as hydrofluoric acid and formic acid at high pressure. It is also seen in the ion [F-H-F]−. Much has been done to explain the symmetric hydrogen bond quantum-mechanically, as it seems to violate the duet rule for the first shell: The proton is effectively surrounded by four electrons. Because of this problem, some consider it to be an ionic bond.

Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been observed recently spectroscopically in formic acid at high pressure (>GPa). Each hydrogen atom forms a partial covalent bond with two atoms rather than one. Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been postulated in ice at high pressure (ice-X). Low-barrier hydrogen bonds form when the distance between two heteroatoms is very small.

Dihydrogen bond

The hydrogen bond can be compared with the closely related dihydrogen bond, which is also an intermolecular bonding interaction involving hydrogen atoms. These structures have been known for some time, and well characterized by crystallography; however, an understanding of their relationship to the conventional hydrogen bond, ionic bond, and covalent bond remains unclear. Generally, the hydrogen bond is characterized by a proton acceptor that is a lone pair of electrons in nonmetallic atoms (most notably in the nitrogen, and chalcogen groups). In some cases, these proton acceptors may be pi-bonds or metal complexes. In the dihydrogen bond, however, a metal hydride serves as a proton acceptor; thus forming a hydrogen-hydrogen interaction. Neutron diffraction has shown that the molecular geometry of these complexes are similar to hydrogen bonds, in that the bond length is very adaptable to the metal complex/hydrogen donor system.

Advanced theory of the hydrogen bond

Recently the nature of the bond was elucidated. A widely publicized article[8] proved from interpretations of the anisotropies in the Compton profile of ordinary ice, that the hydrogen bond is partly covalent. Some NMR data on hydrogen bonds in proteins also indicate covalent bonding.

Most generally, the hydrogen bond can be viewed as a metric-dependent electrostatic scalar field between two or more intermolecular bonds. This is slightly different from the intramolecular bound states of, for example, covalent or ionic bonds; however, hydrogen bonding is generally still a bound state phenomenon, since the interaction energy has a net negative sum. The initial theory of hydrogen bonding proposed by Linus Pauling suggested that the hydrogen bonds had a partial covalent nature. This remained a controversial conclusion until the late 1990's when NMR techniques were employed by F. Cordier et al. to transfer information between hydrogen-bonded nuclei, a feat that would only be possible if the hydrogen bond contained some covalent character. While a lot of experimental data has been recovered for hydrogen bonds in water, for example, that provide good resolution on the scale of intermolecular distances and molecular thermodynamics, the kinetic and dynamical properties of the hydrogen bond in dynamic systems remains unchanged.

Hydrogen bonding phenomena

- Dramatically higher boiling points of NH3, H2O, and HF compared to the heavier analogues PH3, H2S, and HCl

- Viscosity of anhydrous phosphoric acid and of glycerol

- Dimer formation in carboxylic acids and hexamer formation in hydrogen fluoride, which occur even in the gas phase, resulting in gross deviations from the ideal gas law.

- High water solubility of many compounds such as ammonia is explained by hydrogen bonding with water molecules.

- Negative azeotropy of mixtures of HF and water

- Deliquescence of NaOH is caused in part by reaction of OH- with moisture to form hydrogen-bonded H2O3- species. An analogous process happens between NaNH2 and NH3, and between NaF and HF.

- The fact that ice is less dense than liquid water is due to a crystal structure resulting from hydrogen bonds.

- The presence of hydrogen bonds can cause an anomaly in the normal succession of states of matter for certain mixtures of chemical compounds as temperature increases or decreases. These compounds can be liquid until a certain temperature, then solid even as the temperature increases, and finally liquid again as the temperature rises over the "anomaly interval"[9]

References

- ↑ Felix H. Beijer, Huub Kooijman, Anthony L. Spek, Rint P. Sijbesma, E. W. Meijer (1998). "Self-Complementarity Achieved through Quadruple Hydrogen Bonding". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37: 75–78. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980202)37:1/2%3C75::AID-ANIE75%3E3.0.CO;2-R.

- ↑ Template:GoldBookRef

- ↑ Emsley, J. (1980). "Very Strong Hydrogen Bonds". Chemical Society Reviews. 0: 91–124.

- ↑ Omer Markovitch and Noam Agmon (2007). "Structure and energetics of the hydronium hydration shells". J. Phys. Chem. A. 111 (12): 2253–2256. doi:10.1021/jp068960g.

- ↑ W. L. Jorgensen and J. D. Madura (1985). "Temperature and size dependence for Monte Carlo simulations of TIP4P water". Mol. Phys. 56 (6): 1381. doi:10.1080/00268978500103111.

- ↑ Jan Zielkiewicz (2005). "Structural properties of water: Comparison of the SPC, SPCE, TIP4P, and TIP5P models of water". J. Chem. Phys. 123: 104501. doi:10.1063/1.2018637..

- ↑ Damien Laage and James T. Hynes (2006). "A Molecular Jump Mechanism for Water Reorientation". Science. 311: 832. doi:10.1126/science.1122154.

- ↑ E.D. Isaacs, et al., Physical Review Letters vol. 82, pp 600-603 (1999)

- ↑ Law-breaking liquid defies the rules at physicsworld.com

- George A. Jeffrey. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding (Topics in Physical Chemistry). Oxford University Press, USA (March 13, 1997). ISBN 0-19-509549-9

- Robert H. Crabtree, Per E. M. Siegbahn, Odile Eisenstein, Arnold L. Rheingold, and Thomas F. Koetzle (1996). "A New Intermolecular Interaction: Unconventional Hydrogen Bonds with Element-Hydride Bonds as Proton Acceptor". Acc. Chem. Res. 29 (7): 348–354. doi:10.1021/ar950150s.

- Alexander F. Goncharov, M. Riad Manaa, Joseph M. Zaug, Richard H. Gee, Laurence E. Fried, and Wren B. Montgomery (2005). "Polymerization of Formic Acid under High Pressure". Phys. Rev. Lett. 94 (6): 065505. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.065505.

- F. Cordier, M. Rogowski, S. Grzesiek and A. Bax (1999). "Observation of through-hydrogen-bond (2h)J(HC') in a perdeuterated protein". J Magn Reson. 140: 510–2.

- R. Parthasarathi, V. Subramanian, N. Sathyamurthy (2006). "Hydrogen Bonding Without Borders: An Atoms-In-Molecules Perspective". J. Phys. Chem. (A). 110: 3349–3351.

an:Enrastre d'idrocheno

ar:رابطة هيدروجينية

ca:Enllaç d'hidrogen

cs:Vodíková vazba

da:Hydrogenbinding

de:Wasserstoffbrückenbindung

el:Δεσμός υδρογόνου

fa:پیوند هیدروژنی

gl:Enlace de hidróxeno

ko:수소 결합

id:Ikatan hidrogen

it:Legame idrogeno

he:קשר מימן

mk:Водородна врска

nl:Waterstofbrug

no:Hydrogenbinding

nn:Hydrogenbinding

simple:Hydrogen bond

sk:Vodíková väzba

sr:Водонична веза

fi:Vetysidos

sv:Vätebindning

th:พันธะไฮโดรเจน

uk:Водневий зв'язок

Template:Jb1