Histoplasma capsulatum

|

Histoplasmosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Histoplasma capsulatum On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Histoplasma capsulatum |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Histoplasma capsulatum |

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;"|Template:Taxobox name | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

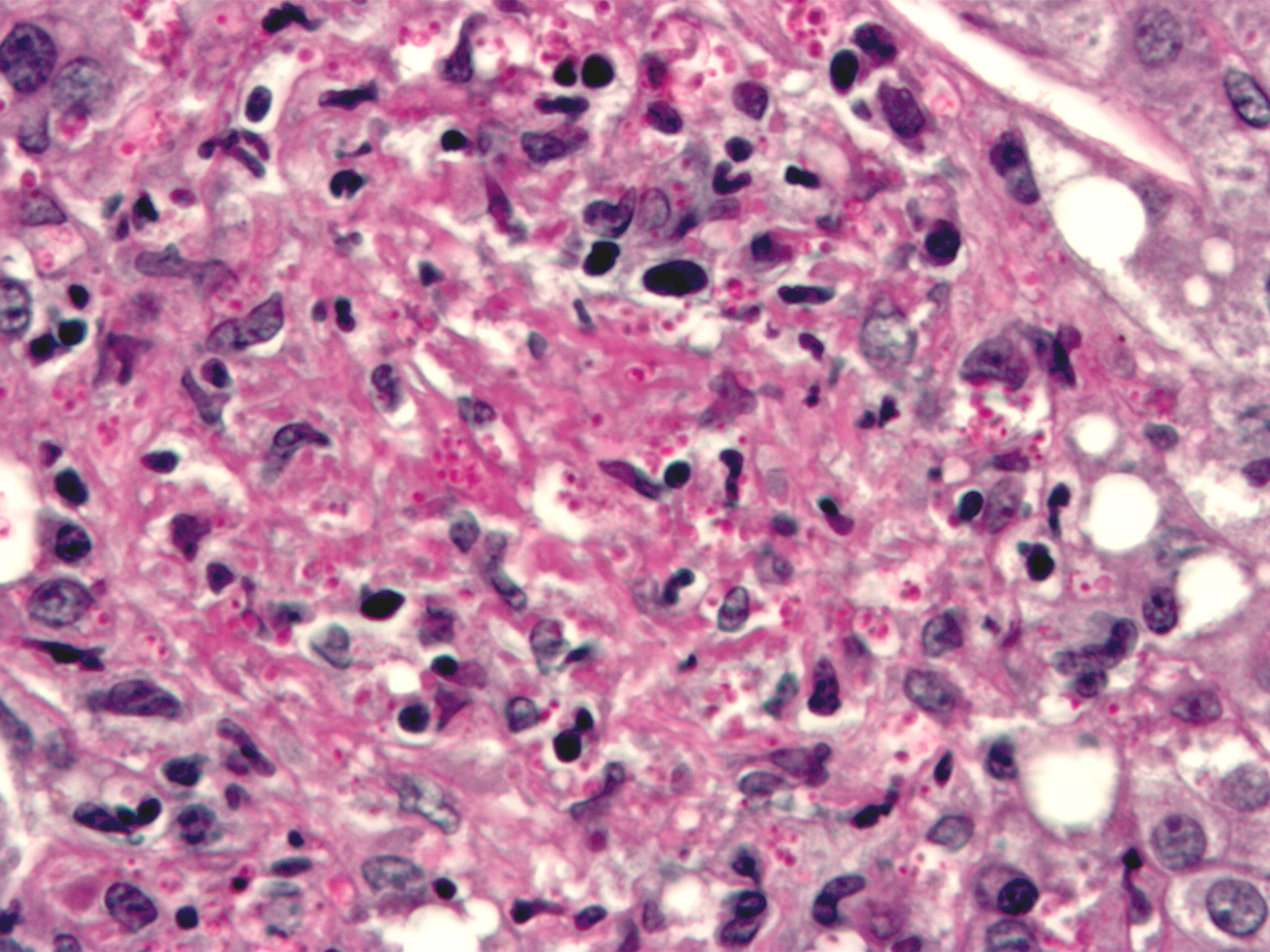

Histoplasma (bright red, small, circular). PAS diastase stain

| ||||||||||||

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;" | Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Type species | ||||||||||||

| Histoplasma capsulatum Darling (1906) | ||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

|

Histoplasma capsulatum |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Serge Korjian M.D.

Overview

Histoplasma capsulatum is a fungus commonly found in bird and bat fecal material and is the causative agent of histoplasmosis.[1] It belongs to the recently recognized fungal family Ajellomycetaceae. It is dimorphic and switches from a mold-like (filamentous) growth form in the natural habitat to a small budding yeast form in the warm-blooded animal host. It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

Growth and morphology

- Histoplasma capsulatum is an ascomycetous fungus.

- It is dimorphic and switches from a mold-like (filamentous) growth form in the natural habitat to a small budding yeast form in the host.

- It is potentially sexual, and its sexual state, Ajellomyces capsulatus, can readily be produced in culture, though it has not been directly observed in nature.

- H. capsulatum groups with B. dermatitidis and the South American pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in the recently recognized fungal family Ajellomycetaceae.[2][3]

- Histoplasma capsulatum has two mating types "+" and "–", as with B. dermatitidis.

- In its asexual form, the fungus grows as a colonial microfungus strongly similar in macromorphology to B. dermatitidis.

- A microscopic examination shows a marked distinction: H. capsulatum produces two types of conidia, globose macroconidia, 8–15 µm, with distinctive tuberculate or finger-like cell wall ornamentation, and ovoid microconidia, 2–4 µm, which appear smooth or finely roughened.

- It is not clear whether one or both of these conidial types is more important than the other as the principal main infectious particles.

- They form on individual short stalks and readily become airborne when the colony is disturbed.

- Ascomata of the sexual state are 80–250 µm, and are very similar in appearance and anatomy to those described above for B. dermatitidis. The ascospores are similarly minute, averaging 1.5 µm.

- The budding yeast cells formed in infected tissues are small (ca. 2–4 µm) and are characteristically seen forming in clusters within phagocytic cells, including histiocytes and other macrophages, as well as monocytes.

Geographic distribution

- The endemic zones of H. capsulatum can be roughly divided into core areas, where the fungus occurs widely in soil or on vegetation contaminated by bird droppings or equivalent organic inputs, and peripheral areas, where the fungus occurs relatively rarely in association with soil but is still found abundantly in heavy accumulations of bat or bird guano in enclosed spaces such as caves, buildings, and hollow trees.

- The principal core area for this species includes the valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio and Potomac rivers in the USA as well as a wide span of adjacent areas extending from Kansas, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio in the north to Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas in the south.[4][5][6]

- In some areas, such as Kansas City, skin testing with the histoplasmin antigen preparation shows that 80–90 % of the resident population have an antibody reaction to H. capsulatum, probably indicating prior subclinical infection.[4]

- Northern U.S. states such as Minnesota, Michigan, New York and Vermont are peripheral areas for histoplasmosis, but have scattered counties where 5–19 % of lifetime residents show exposure to H. capsulatum.

Ecology

- Histoplasma capsulatum appears to be strongly associated with the droppings of certain bird species as well as bats.[4]

- A mixture of these droppings and certain soil types is particularly conducive to proliferation.

- In highly endemic areas there is a strong association with soil under and around chicken houses, and with areas where soil or vegetation has become heavily contaminated with fecal material deposited by flocking birds such as starlings and blackbirds.

- Bird roosting areas that are Histoplasma-free appear to be lower in nitrogen, phosphorus, organic matter and moisture than contaminated roosting areas.[4]

- The guano of gulls and other colonially nesting water-associated birds is rarely connected to histoplasmosis.[7]

- Bat dwellings, including caves, attics and hollow trees, are classic H. capsulatum habitats.[4][8]

- Histoplasmosis outbreaks are typically associated with cleaning guano accumulations or clearing guano-covered vegetation, or with exploration of bat caves.

- In addition, however, outbreaks may be associated with wind-blown dust liberated by construction projects in endemic areas: a classic outbreak is one associated with intense construction activity, including subway construction, in Montreal in 1963.[9]

- As with blastomycosis, a good understanding of the precise ecological affinities of H. capsulatum is greatly complicated by the difficulty of isolating the fungus directly from nature.

Gallery

-

Photomicrograph reveals some of the ultrastructural details exhibited by Histoplasma capsulatum fungal organisms that had been extracted from a Jamaican isolate, which included a number of tuberculate (knobby) spheroidal macroconidia, and diaphanous filamentous hyphae (800X). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [10]

-

This Giemsa-stained photomicrograph reveals numerous Histoplasma capsulatum fungal organisms in their yeast-stage of development, which were seen in this liver tissue specimen, in this case of disseminated histoplasmosis. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [10]

References

- ↑ McGinnis MR, Tyring SK (1996). Introduction to Mycology. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Untereiner, W.A.; Scott, J.A.; Naveau, F.A.; Bachewich, J. (2002). "Phylogeny of Ajellomyces, Polytolypa and Spiromastix (Onygenaceae) inferred from rDNA sequence and non-molecular data". Studies in Mycology. 47: 25–35.

- ↑ Untereiner, WA; Scott, JA; Naveau, FA; Sigler, L; Bachewich, J; Angus, A (2004). "The Ajellomycetaceae, a new family of vertebrate-associated Onygenales". Mycologia. 96 (4): 812–821. PMID 21148901.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Kwon-Chung, K. June; Bennett, Joan E. (1992). Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. ISBN 0812114639.

- ↑ Chamany, S; Mirza, SA; Fleming, JW; Howell, JF; Lenhart, SW; Mortimer, VD; Phelan, MA; Lindsley, MD; Iqbal, NJ; Wheat, LJ; Brandt, ME; Warnock, DW; Hajjeh, RA (2004). "A large histoplasmosis outbreak among high school students in Indiana, 2001". The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 23 (10): 909–14. PMID 15602189.

- ↑ Stobierski, MG; Hospedales, CJ; Hall, WN; Robinson-Dunn, B; Hoch, D; Sheill, DA (1996). "Outbreak of histoplasmosis among employees in a paper factory--Michigan, 1993". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 34 (5): 1220–1223. PMID 8727906.

- ↑ Waldman, RJ; England, AC; Tauxe, R; Kline, T; Weeks, RJ; Ajello, L; Kaufman, L; Wentworth, B; Fraser, DW (1983). "A winter outbreak of acute histoplasmosis in northern Michigan". American Journal of Epidemiology. 117 (1): 68–75. PMID 6823954.

- ↑ Rippon, John Willard (1988). Medical mycology: the pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 0721624448.

- ↑ Leznoff, A; Frank, H; Telner, P; Rosensweig, J; Brandt, JL (1964). "Histoplasmosis in Montreal during the fall of 1963, with observations on erythema multiforme". Canadian Medical Association journal. 91: 1154–1160. PMID 14226089.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

![Photomicrograph reveals some of the ultrastructural details exhibited by Histoplasma capsulatum fungal organisms that had been extracted from a Jamaican isolate, which included a number of tuberculate (knobby) spheroidal macroconidia, and diaphanous filamentous hyphae (800X). From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [10]](/images/f/fe/Histoplasmosis02.jpeg)

![This Giemsa-stained photomicrograph reveals numerous Histoplasma capsulatum fungal organisms in their yeast-stage of development, which were seen in this liver tissue specimen, in this case of disseminated histoplasmosis. From Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [10]](/images/5/56/Histoplasmosis01.jpeg)