Herpangina

|

WikiDoc Resources for Herpangina |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Herpangina |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Herpangina at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Herpangina at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Herpangina

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Herpangina Discussion groups on Herpangina Patient Handouts on Herpangina Directions to Hospitals Treating Herpangina Risk calculators and risk factors for Herpangina

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Herpangina |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Fatimo Biobaku M.B.B.S [2]

Synonyms: Vesicular stomatitis, Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis

Overview

Herpangina is a self-limited infection of the upper respiratory tract caused by enteroviruses.[1] Serotypes of coxsackie A virus are frequently implicated. Outbreaks of herpangina often occur during the summer period, and the pediatric age group is predominantly affected.[2] Herpangina often begins with a sudden fever, sore throat, dysphagia, and the appearance of the enanthem. The diagnosis is usually clinical and it generally resolves within one week of infection without any sequelae.[1]

Historical Perspective

The name 'herpangina' was coined by Zahorsky, and he was also the first person to give a full description of the clinical entitity in 1920.[3] The first isolation and description of the coxsackie virus was in 1948 by Dalldorf and Sickles.[3]

Causes

Herpangina is caused by enteroviruses. The majority of herpangina cases are caused by coxsackie A viruses (commonly A1, A2, A6, A8, A10, A16, and A22) but it can also be caused by other enteroviruses such as some serotypes of coxsackie B virus, echovirus and enterovirus 71.[1][4][2]

Pathophysiology

The mode of transmission of enteroviruses is usually via fecal–oral transmission.[5] However, enteroviruses can also be spread through contact with virus-contaminated oral secretions, vesicular fluid, contaminated surfaces or fomites, and viral respiratory droplets.[6][5] Following ingestion of the enterovirus, viral replication occurs in the lymphoid tissues of the oropharyngeal cavity and the small bowel (Peyer's patches).[5] Dissemination of enteroviruses to the reticuloendothelial system and other parts of the body such as the skin and mucous membranes can occur, and this coincides with the onset of the clinical features.[5]

Risk Factors

Some of the risk factors that have been found to be associated with herpangina are:[7][8]

- Attendance at a kindergarten/child care center

- Contact with herpangina cases

- Residence in rural areas

- Overcrowding

- Poor hygiene

- Low socioeconomic status

Differential Diagnosis

The following diseases may mimic herpangina:[1][2]

- Herpetic gingivostomatitis- This is caused by herpes simplex virus(HSV) infection, and affects the anterior oral cavity. It commonly affects the inner parts of the lips, the buccal mucosa, and the tongue. Gingivitis and cervical lymphadenitis can be seen in HSV infection but these are usually absent in herpangina.

- Bacterial pharyngitis

- Tonsillitis

- Aphthous stomatitis

- Hand-foot-mouth disease

Oral lesions caused by herpangina must be differentiated from other diseases presenting with pain and blistering within the mouth (gingivostomatitis and glossitis). The differentials include:

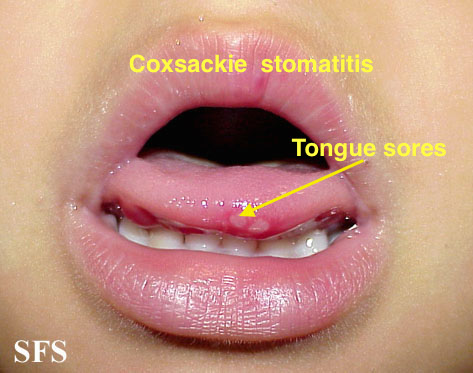

| Disease | Presentation | Risk Factors | Diagnosis | Affected Organ Systems | Important features | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxsackie virus |

|

|

| |||

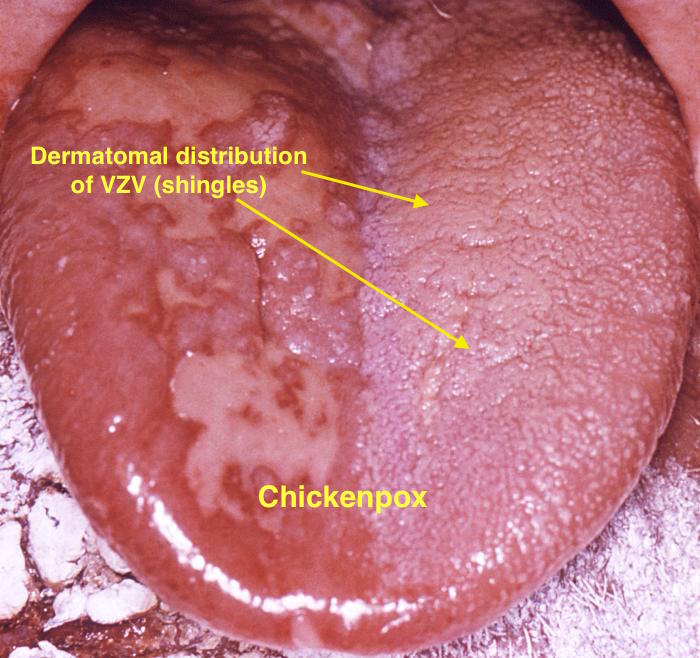

| Chicken pox |

|

|

|

|

| |

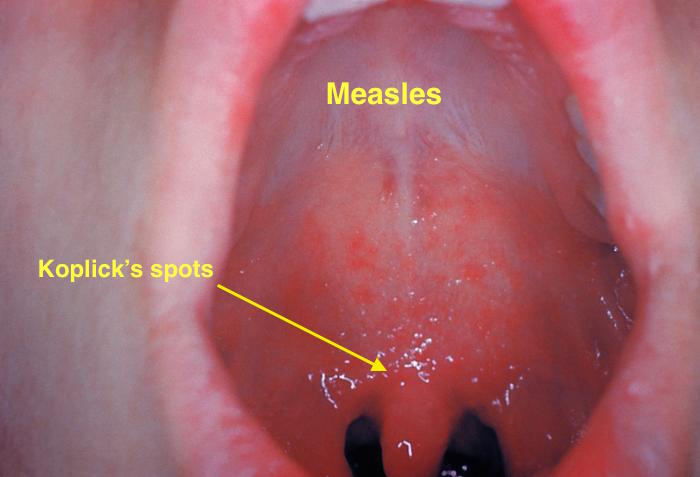

| Measles |

|

|

|

|

| |

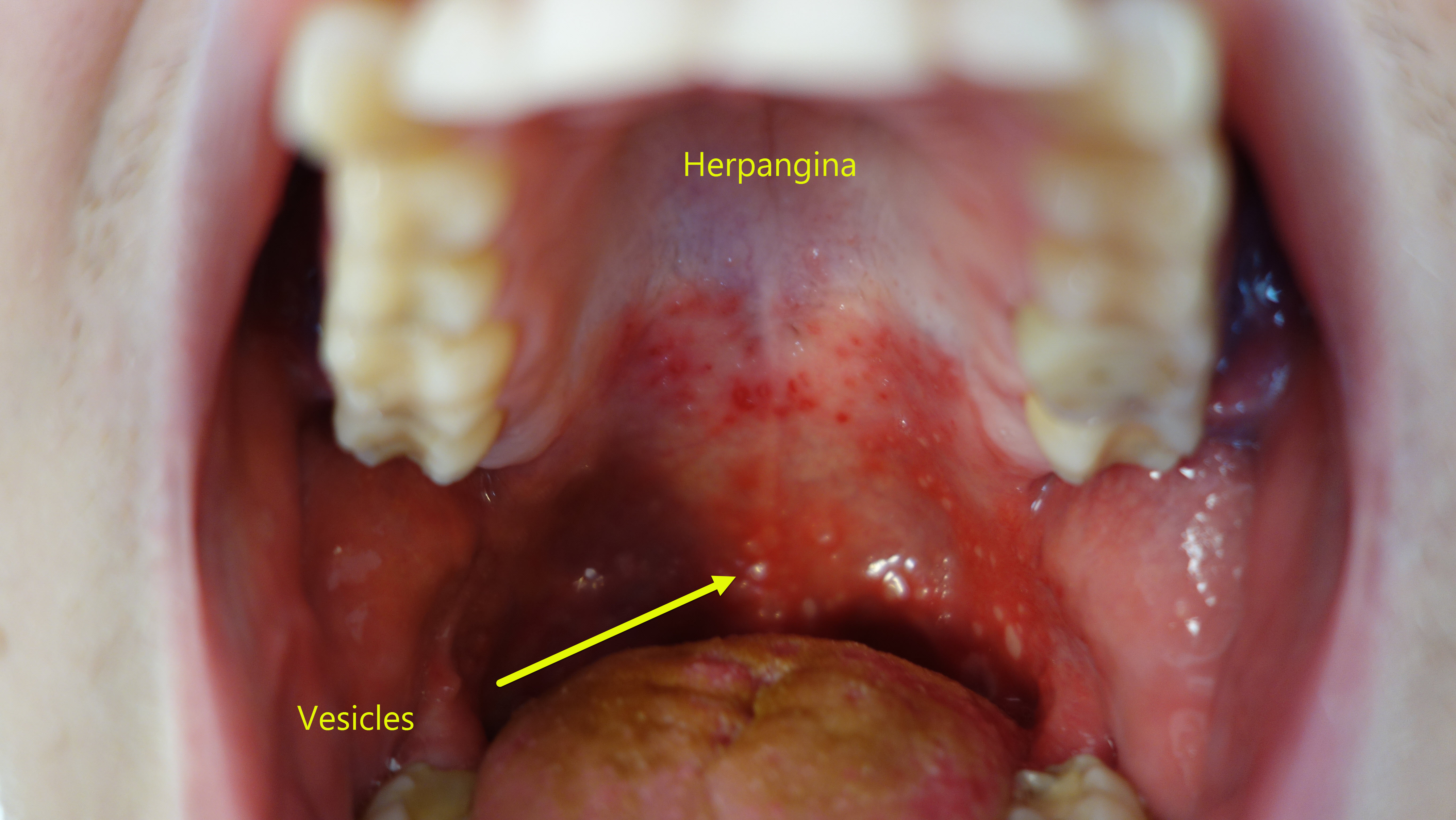

| Herpangina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Primary herpetic gingivoestomatitis[11] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oral Candidiasis |

|

|

Localized candidiasis

Invasive candidasis |

|

|

Epidemiology

Incidence

The incidence of herpangina has been found to have seasonal variations and there is usually a peak in the incidence during the summer season.[13] The incidence was studied for a period of 8 years in Taiwan and was found to vary between 0.8-19.9 cases per sentinel physician per week.[13]

Age

Herpangina is seen predominantly in children and summer outbreaks are not uncommon.[2] It occurs more frequently in children between the ages of 3-10yrs.[1][2] Adolescents and young adults are occasionally affected.[2]

Sex

There is no known sex predilection.[1]

Natural History, Complications, Prognosis

Natural History

Herpangina is a self-limited infection of the upper respiratory tract.[1]

Complications

Complications such as meningitis rarely occurs.[8]

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent and complete resolution generally occurs in a week.[1]

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

The history and symptoms may include the following:[2][1]

- Sudden fever

- Sore throat and dysphagia- These can occur several hours(up to 24 hours), before the appearance of the enanthem.

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Myalgia

- Headache

- Pharyngeal lesions

- Most patients do not appear severely ill

Physical Examination

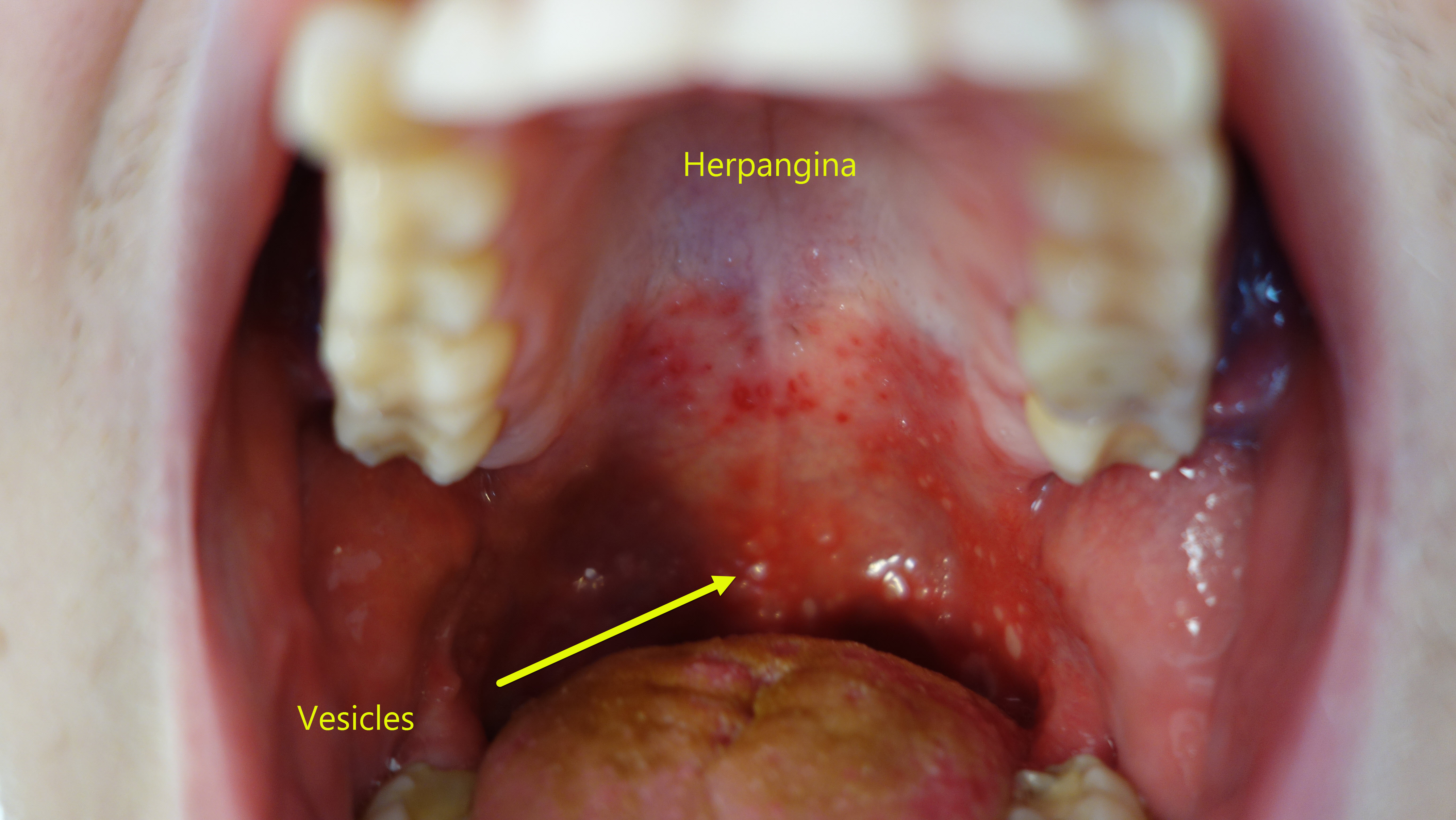

Examination of the throat can reveal the following:[2]

- Erythema

- Exudate of the tonsils which is usually mild.

- Characteristic enanthem- Punctate macule which evolve over a period of 24 hours to 2-4mm erythematous papules which vesiculate, and then centrally ulcerate.

- The lesions are usually small in number, and evolve rapidly. The lesions are seen more commonly on the soft palate and uvula. The lesions can also be seen on the tonsils, posterior pharyngeal wall and the buccal mucosa.

Laboratory Tests[1]

- The diagnosis of herpangina is clinical.

- When unsure of the diagnosis, pharyngeal viral and bacterial cultures can be taken to exclude HSV infection and streptococcal pharyngitis.

- Approximately 1 week after infection, type-specific antibodies appear in the blood with maximum titer occurring in 3 weeks.

Treatment

Herpangina is a self-limited infection, and the treatment comprises the management of the symptoms. This entails:[1]

- Symptomatic treatment of sore throat with saline gargles, analgesic throat lozenges and liberal oral fluid intake.

- Analgesic medications for pain

- Antipyretic medications when indicated

- Avoidance of antiviral and antibacterial medications as symptoms generally resolve within 1 week.

Prevention

The prevention of herpangina is best achieved by adoption of infection control practices such as:[14]

- Good personal hygiene like hand-washing.

- Cleaning and disinfection of premises and objects/articles.

- Ensuring infected children are quarantined.

References

Template:WH Template:WikiDoc Sources

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Ferri, Fred (2017). "Chapter:Herpangina". Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017. Elsevier. pp. 583–583. ISBN 978-0-3232-8048-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Durand, Marlene (2015). "Chapter 174:Coxsackieviruses, Echoviruses, and Numbered Enteroviruses(EV-D68)". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases Updated Edition, Eighth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 2080–2090. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 HOWLETT JG, SOMLO F, KALZ F (1957). "A new syndrome of parotitis with herpangina caused by the Coxsackie virus". Can Med Assoc J. 77 (1): 5–7. PMC 1823836. PMID 13437259.

- ↑ Li W, Gao HH, Zhang Q, Liu YJ, Tao R, Cheng YP; et al. (2016). "Large outbreak of herpangina in children caused by enterovirus in summer of 2015 in Hangzhou, China". Sci Rep. 6: 35388. doi:10.1038/srep35388. PMC 5067559. PMID 27752104.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, McMinn P, Ooi MH (2010). "Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71". Lancet Infect Dis. 10 (11): 778–90. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8. PMID 20961813.

- ↑ Muehlenbachs A, Bhatnagar J, Zaki SR (2015). "Tissue tropism, pathology and pathogenesis of enterovirus infection". J Pathol. 235 (2): 217–28. doi:10.1002/path.4438. PMID 25211036.

- ↑ Chang LY, King CC, Hsu KH, Ning HC, Tsao KC, Li CC; et al. (2002). "Risk factors of enterovirus 71 infection and associated hand, foot, and mouth disease/herpangina in children during an epidemic in Taiwan". Pediatrics. 109 (6): e88. PMID 12042582.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kliegman, Robert; Stanton, Bonita; St. Geme, Joseph; Schor, Nina (2016). "Chapter 250:Nonpolio Enteroviruses". Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics Twentieth Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1561–1568. ISBN 978-1-4557-7566-8.

- ↑ Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE (2000). "Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization". JAMA. 284 (24): 3145–50. PMID 11135778.

- ↑ Ratnam S, West R, Gadag V, Williams B, Oates E (1996). "Immunity against measles in school-aged children: implications for measles revaccination strategies". Can J Public Health. 87 (6): 407–10. PMID 9009400.

- ↑ Kolokotronis, A.; Doumas, S. (2006). "Herpes simplex virus infection, with particular reference to the progression and complications of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 12 (3): 202–211. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01336.x. ISSN 1198-743X.

- ↑ Chauvin PJ, Ajar AH (2002). "Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis in adults: a review of 13 cases, including diagnosis and management". J Can Dent Assoc. 68 (4): 247–51. PMID 12626280.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chen KT, Chang HL, Wang ST, Cheng YT, Yang JY (2007). "Epidemiologic features of hand-foot-mouth disease and herpangina caused by enterovirus 71 in Taiwan, 1998-2005". Pediatrics. 120 (2): e244–52. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-3331. PMID 17671037.

- ↑ Kok CC (2015). "Therapeutic and prevention strategies against human enterovirus 71 infection". World J Virol. 4 (2): 78–95. doi:10.5501/wjv.v4.i2.78. PMC 4419123. PMID 25964873.