Medicine

|

WikiDoc Resources for Medicine |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Medicine |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Medicine at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Medicine at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Medicine

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Medicine Risk calculators and risk factors for Medicine

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Medicine |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Medicine is the science and "art" of maintaining and/or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of patients. The term is derived from the Latin ars medicina meaning the art of healing. [1][2]

The modern practice of medicine occurs at the many interfaces between the art of healing and various sciences. Medicine is directly connected to the health sciences and biomedicine. Broadly speaking, the term 'Medicine' today refers to the fields of clinical medicine, medical research and surgery, thereby covering the challenges of disease and injury.

Overview

Since the 19th century, only those with a medical degree have been considered worthy to practice medicine. Clinicians (licensed professionals who deal with patients) can be physicians, physical therapists, physician assistants, nurses or others. The medical profession is the social and occupational structure of the group of people formally trained and authorized to apply medical knowledge. Many countries and legal jurisdictions have legal limitations on who may practice medicine.

Medicine comprises various specialized sub-branches, such as cardiology, pulmonology, neurology, or other fields such as sports medicine, research or public health.

Human societies have had various different systems of health care practice since at least the beginning of recorded history. Medicine, in the modern period, is the mainstream scientific tradition which developed in the Western world since the early Renaissance (around 1450). Many other traditions of health care are still practiced throughout the world; most of these are separate from Western medicine, which is also called biomedicine, allopathic medicine or the Hippocratic tradition. The most highly developed of these are traditional Chinese medicine, Traditional Tibetan medicine and the Ayurvedic traditions of India and Sri Lanka. Various non-mainstream traditions of health care have also developed in the Western world. These systems are sometimes considered companions to Hippocratic medicine, and sometimes are seen as competition to the Western tradition. Few of them have any scientific confirmation of their tenets, because if they did they would be brought into the fold of Western medicine.

"Medicine" is also often used amongst medical professionals as shorthand for internal medicine. Veterinary medicine is the practice of health care in animal species other than human beings.

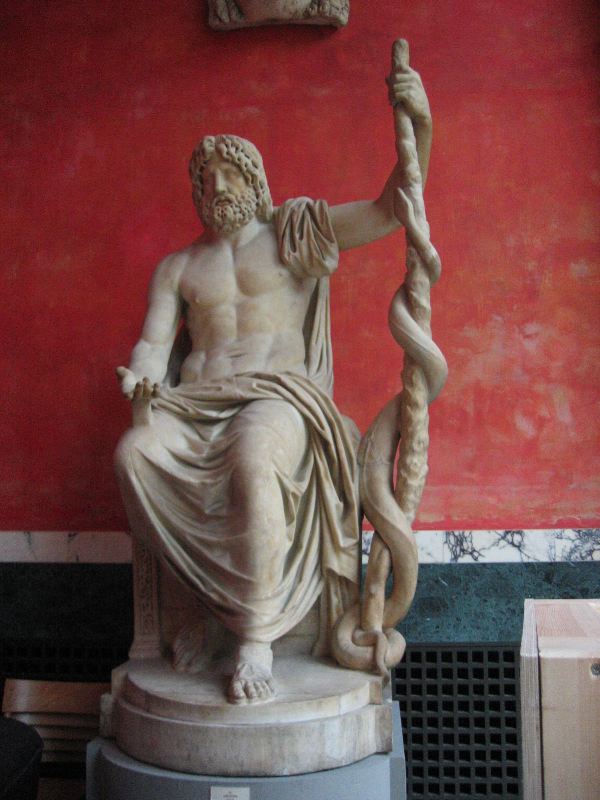

History of medicine

The earliest type of medicine in most cultures was the use of plants (Herbalism) and animal parts. This was usually in concert with 'magic' of various kinds in which: animism (the notion of inanimate objects having spirits); spiritualism (here meaning an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits); shamanism (the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); and divination (the supposed obtaining of truth by magic means), played a major role.

The practice of medicine developed gradually, and separately, in Ancient Egypt, Ancient India, Ancient China, Ancient Greece, Ancient Persia and elsewhere. Medicine as it is practiced now developed largely in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century in England (William Harvey, seventeenth century), Germany (Rudolf Virchow) and France (Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard and others). The new, "scientific" medicine (where results are testable and repeatable) replaced early Western traditions of medicine, based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other pre-modern theories. The focal points of development of clinical medicine shifted to the United Kingdom and the USA by the early 1900s (Canadian-born) Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing). Possibly the major shift in medical thinking was the gradual rejection in the 1400s during the Black Death of what may be called the 'traditional authority' approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that because some prominent person in the past said something must be so, then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European society in general - see Copernicus's rejection of Ptolemy's theories on astronomy). People like Vesalius led the way in improving upon or indeed rejecting the theories of great authorities from the past such as Galen, Hippocrates, and Avicenna/Ibn Sina, all of whose theories were in time almost totally discredited. Such new attitudes were also only made possible by the weakening of the Roman Catholic church's power in society, especially in the Republic of Venice.

Evidence-based medicine is a recent movement to establish the most effective algorithms of practice (ways of doing things) through the use of the scientific method and modern global information science by collating all the evidence and developing standard protocols which are then disseminated to healthcare providers. One problem with this 'best practice' approach is that it could be seen to stifle novel approaches to treatment.

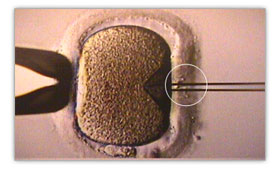

Genomics and knowledge of human genetics is already having some influence on medicine, as the causative genes of most monogenic genetic disorders have now been identified, and the development of techniques in molecular biology and genetics are influencing medical practice and decision-making.

Pharmacology has developed from herbalism and many drugs are still derived from plants (atropine, ephedrine, warfarin, aspirin, digoxin, vinca alkaloids, taxol, hyoscine, etc). The modern era began with Robert Koch's discoveries around 1880 of the transmission of disease by bacteria, and then the discovery of antibiotics shortly thereafter around 1900. The first of these was arsphenamine / Salvarsan discovered by Paul Ehrlich in 1908 after he observed that bacteria took up toxic dyes that human cells did not. The first major class of antibiotics was the sulfa drugs, derived by French chemists originally from azo dyes. Throughout the twentieth century, major advances in the treatment of infectious diseases were observable in (Western) societies. The medical establishment is now developing drugs targeted towards one particular disease process. Thus drugs are being developed to minimise the side effects of prescribed drugs, to treat cancer, geriatric problems, long-term problems (such as high cholesterol), chronic diseases type 2 diabetes, lifestyle and degenerative diseases such as arthritis and Alzheimer's disease.

Practice of medicine

The practice of medicine combines both science as the evidence base and art in the application of this medical knowledge in combination with intuition and clinical judgment to determine the treatment plan for each patient.

Central to medicine is the patient-physician relationship established when a person with a health concern seeks a physician's help; the 'medical encounter'. Other health professionals similarly establish a relationship with a patient and may perform various interventions, e.g. nurses, radiographers and therapists.

As part of the medical encounter, the healthcare provider needs to:

- develop a relationship with the patient

- gather data (medical history, systems enquiry, and physical examination, combined with laboratory or imaging studies (investigations))

- analyze and synthesize that data (assessment and/or differential diagnoses), and then:

- develop a treatment plan (further testing, therapy, watchful observation, referral and follow-up)

- treat the patient accordingly

- assess the progress of treatment and alter the plan as necessary (management).

The medical encounter is documented in a medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[3]

Health care delivery systems

Medicine is practiced within the medical system, which is a legal, credentialing and financing framework, established by a particular culture or government. The characteristics of a health care system have significant effect on the way medical care is delivered.

Financing has a great influence as it defines who pays the costs. Aside from tribal cultures, the most significant divide in developed countries is between universal health care and market-based health care (such as practiced in the U.S.). Universal health care might allow or ban a parallel private market. The latter is described as single-payer system.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality and pricing greatly affects the choice by patients / consumers and therefore the incentives of medical professionals. While US health care system has come under fire for lack of openness, new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other.

Health care delivery

Medical care delivery is classified into primary, secondary and tertiary care.

Primary care medical services are provided by physicians or other health professionals who have first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician offices, clinics, nursing homes, schools, home visits and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sexes.

Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, emergency rooms, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary care medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information - still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays by electronic means.

Patient-physician-relationship

This kind of relationship and interaction is a central process in the practice of medicine. There are many perspectives from which to understand and describe it.

An idealized physician's perspective, such as is taught in medical school, sees the core aspects of the process as the physician learning the patient's symptoms, concerns and values; in response the physician examines the patient, interprets the symptoms, and formulates a diagnosis to explain the symptoms and their cause to the patient and to propose a treatment. The job of a physician is similar to a human biologist: that is, to know the human frame and situation in terms of normality. Once the physician knows what is normal and can measure the patient against those norms, he or she can then determine the particular departure from the normal and the degree of departure. This is called the diagnosis.

The four great cornerstones of diagnostic medicine are anatomy (structure: what is there), physiology (how the structure/s work), pathology (what goes wrong with the anatomy and physiology) and psychology (mind and behavior). In addition, the physician should consider the patient in their 'well' context rather than simply as a walking medical condition. This means the socio-political context of the patient (family, work, stress, beliefs) should be assessed as it often offers vital clues to the patient's condition and further management. In more detail, the patient presents a set of complaints (the symptoms) to the physician, who then obtains further information about the patient's symptoms, previous state of health, living conditions, and so forth. The physician then makes a review of systems (ROS) or systems inquiry, which is a set of ordered questions about each major body system in order: general (such as weight loss), endocrine, cardio-respiratory, etc. Next comes the actual physical examination; the findings are recorded, leading to a list of possible diagnoses. These will be in order of probability. The next task is to enlist the patient's agreement to a management plan, which will include treatment as well as plans for follow-up. Importantly, during this process the healthcare provider educates the patient about the causes, progression, outcomes, and possible treatments of his ailments, as well as often providing advice for maintaining health. This teaching relationship is the basis of calling the physician doctor, which originally meant "teacher" in Latin. The patient-physician relationship is additionally complicated by the patient's suffering (patient derives from the Latin patior, "suffer") and limited ability to relieve it on his/her own. The physician's expertise comes from his knowledge of what is healthy and normal contrasted with knowledge and experience of other people who have suffered similar symptoms (unhealthy and abnormal), and the proven ability to relieve it with medicines (pharmacology) or other therapies about which the patient may initially have little knowledge.

The physician-patient relationship can be analyzed from the perspective of ethical concerns, in terms of how well the goals of non-maleficence, beneficence, autonomy, and justice are achieved. Many other values and ethical issues can be added to these. In different societies, periods, and cultures, different values may be assigned different priorities. For example, in the last 30 years medical care in the Western World has increasingly emphasized patient autonomy in decision making.

The relationship and process can also be analyzed in terms of social power relationships (e.g., by Michel Foucault), or economic transactions. Physicians have been accorded gradually higher status and respect over the last century, and they have been entrusted with control of access to prescription medicines as a public health measure. This represents a concentration of power and carries both advantages and disadvantages to particular kinds of patients with particular kinds of conditions. A further twist has occurred in the last 25 years as costs of medical care have risen, and a third party (an insurance company or government agency) now often insists upon a share of decision-making power for a variety of reasons, reducing freedom of choice of healthcare providers and patients in many ways.

The quality of the patient-physician relationship is important to both parties. The better the relationship in terms of mutual respect, knowledge, trust, shared values and perspectives about disease and life, and time available, the better will be the amount and quality of information about the patient's disease transferred in both directions, enhancing accuracy of diagnosis and increasing the patient's knowledge about the disease. Where such a relationship is poor the physician's ability to make a full assessment is compromised and the patient is more likely to distrust the diagnosis and proposed treatment. In these circumstances and also in cases where there is genuine divergence of medical opinions, a second opinion from another physician may be sought.

In some settings, e.g. the hospital ward, the patient-physician relationship is much more complex, and many other people are involved when somebody is ill: relatives, neighbors, rescue specialists, nurses, technical personnel, social workers and others.

Clinical skills

A complete medical evaluation includes a medical history, a systems enquiry, a physical examination, appropriate laboratory or imaging studies, analysis of data and medical decision making to obtain diagnoses, and a treatment plan.[4]

The components of the medical history are:

- Chief complaint (CC): the reason for the current medical visit. These are the 'symptoms.' They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the duration of each one. Also called 'presenting complaint.'

- History of present illness / complaint (HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further clarification of each symptom.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Medications (DHx): what drugs the patient takes including prescribed, over-the-counter, and home remedies, as well as alternative and herbal medicines/herbal remedies such as St John's wort. Allergies are also recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, past infectious diseases and/or vaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (including diet, medications, tobacco, alcohol).

- Family history (FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. A family tree is sometimes used.

- Review of systems (ROS) or systems inquiry: a set of additional questions to ask which may be missed on HPI: a general enquiry (have you noticed any weight loss, fevers, lumps and bumps? etc), followed by questions on the body's main organ systems (heart, lungs, digestive tract, urinary tract, etc).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient looking for signs of disease ('Symptoms' are what the patient volunteers, 'Signs' are what the healthcare provider detects by examination). The healthcare provider uses the senses of sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (taste has been made redundant by the availability of modern lab tests). Four chief methods are used: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen); smelling may be useful (e.g. infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). The clinical examination involves study of:

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor or clubbing)

- Skin

- Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)

- Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessels)

- Respiratory (large airways and lungs)

- Abdomen and rectum

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Musculoskeletal (spine and extremities)

- Neurological (consciousness, awareness, brain, cranial nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves)

- Psychiatric (orientation, mental state, evidence of abnormal perception or thought)

Laboratory and imaging studies results may be obtained, if necessary.

The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

The treatment plan may include ordering additional laboratory tests and studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised.

This process is used by primary care providers as well as specialists. It may take only a few minutes if the problem is simple and straightforward. On the other hand, it may take weeks in a patient who has been hospitalized with bizarre symptoms or multi-system problems, with involvement by several specialists.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations.

Branches of medicine

Working together as an interdisciplinary team, many highly trained health profession also besides medical practitioners are involved in the delivery of modern health care. Some examples include: nurse(s) emergency medical technicians and paramedics, laboratory scientists, (pharmacy, pharmacists), (physiotherapy,physiotherapists), respiratory therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, radiographers, dietitians and bioengineers.

The scope and sciences underpinning human medicine overlap many other fields. Dentistry and psychology, while separate disciplines from medicine, are considered medical fields.

- Midlevel Practitioners

- Nurse practitioners, midwives and physician assistants, treat patients and prescribe medication in many legal jurisdictions.

- Veterinary Medicine

- Veterinarians apply similar techniques as physicians to the care of animals. The original focus of veterinary medicine was primarily the health care of domestic animals. In recent years the discipline has broadened to include all vertebrate animals and even some of the more economically valuable or scientifically interesting invertebrates. Veterinary and human medicine had similar origins but diverged in the West largely under the influence of Christian doctrine which emphasized a fundamental difference between humans and all other species. The two disciplines re-converged to some degree after the Renaissance when scientific study of anatomy and physiology revealed undeniable similarities between humans and other animals. The similarities further extend into pathology and disease control leading the early pioneer in scientific pathology Rudolph Virchow to proclaim the doctrine of "one medicine."

Physicians have many specializations and subspecializations which are listed below. There are variations from country to country regarding which specialties certain subspecialities are in.

Diagnostic specialties

- Clinical laboratory sciences are the clinical diagnostic services which apply laboratory techniques to diagnosis and management of patients. In the United States these services are supervised by a pathologist. The personnel that work in these medical laboratory departments are technically trained staff, each of whom usually hold a medical technology degree, who actually perform the tests, assays, and procedures needed for providing the specific services.

- Pathology is the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific medical knowledge and plays a large role in evidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such as flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, gene rearragements studies and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) fall within the territory of pathology.

- Radiology is concerned with imaging of the human body, e.g. by x-rays, x-ray computed tomography, ultrasonography, and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography.

Clinical disciplines

- Anesthesiology (AE) or anaesthesia (BE) is the clinical discipline concerned with providing anesthesia. Pain medicine is often practiced by specialised anesthesiologists/anesthetists.

- Dermatology is concerned with the skin and its diseases. In the UK, dermatology is a subspeciality of general medicine.

- Emergency medicine is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, including trauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- Gender-based medicine studies the biological and physiological differences between the human sexes and how that affects differences in disease.

- General practice, family practice, family medicine or primary care is, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with non-emergency medical problems. Family practitioners are usually able to treat over 90% of all complaints without referring to specialists.

- Geriatrics focuses on health promotion and the prevention and treatment of disease and disability in later life.

- Hospital medicine is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Physicians whose primary professional focus is hospital medicine are called hospitalists in the USA.

- Internal medicine is concerned with systemic diseases of adults, i.e. those diseases that affect the body as a whole (restrictive, current meaning), or with all adult non-operative somatic medicine (traditional, inclusive meaning), thus excluding pediatrics, surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics, and psychiatry. There are several subdisciplines of internal medicine:

- Neurology is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of nervous system diseases. It is a subspeciality of general medicine in the UK.

- Obstetrics and gynaecology (often abbreviated as Ob/Gyn) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs. Reproductive medicine and fertility medicine are generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Palliative care is a relatively modern branch of clinical medicine that deals with pain and symptom relief and emotional support in patients with terminal illnesses including cancer and heart failure.

- Pediatrics (AE) or paediatrics (BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialities for specific age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery. Most subspecialities of adult medicine have a pediatric equivalent such as pediatric cardiology, pediatric endocrinology, pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric hematology, pediatric oncology, pediatric ophthalmology, and neonatology.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation (or physiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, or congenital disorders.

- Preventive medicine is the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

- Psychiatry is the branch of medicine concerned with the bio-psycho-social study of the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral disorders. Related non-medical fields include psychotherapy and clinical psychology.

- Radiation therapy is concerned with the therapeutic use of ionizing radiation and high energy elementary particle beams in patient treatment.

- Radiology is concerned with the interpretation of imaging modalities including x-rays, ultrasound, radioisotopes, and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). A newer branch of radiology, interventional radiology, is concerned with using medical devices to access areas of the body with minimally invasive techniques.

- Surgical specialties employ operative treatment. These include Orthopedics, Urology, Ophthalmology, Neurosurgery, Plastic Surgery, Otolaryngology and various subspecialties such as transplant and cardiothoracic. Some disciplines are highly specialized and are often not considered subdisciplines of surgery, although their naming might suggest so.

- Urgent care focuses on delivery of unscheduled, walk-in care outside of the hospital emergency department for injuries and illnesses that are not severe enough to require care in an emergency department.

Interdisciplinary fields

Interdisciplinary sub-specialties of medicine are:

- Aerospace medicine deals with medical problems related to flying and space travel.

- Bioethics is a field of study which concerns the relationship between biology, science, medicine and ethics, philosophy and theology.

- Biomedical Engineering is a field dealing with the application of engineering principles to medical practice.

- Clinical pharmacology is concerned with how systems of therapeutics interact with patients.

- Conservation medicine studies the relationship between human and animal health, and environmental conditions. Also known as ecological medicine, environmental medicine, or medical geology.

- Disaster medicine deals with medical aspects of emergency preparedness, disaster mitigation and management.

- Diving medicine (or hyperbaric medicine) is the prevention and treatment of diving-related problems.

- Evolutionary medicine is a perspective on medicine derived through applying evolutionary theory.

- Forensic medicine deals with medical questions in legal context, such as determination of the time and cause of death.

- Keraunomedicine is the medical study of lightning casualties.

- Medical humanities includes the humanities (literature, philosophy, ethics, history and religion), social science (anthropology, cultural studies, psychology, sociology), and the arts (literature, theater, film, and visual arts) and their application to medical education and practice.

- Medical informatics, medical computer science, medical information and eHealth are relatively recent fields that deal with the application of computers and information technology to medicine.

- Naturopathic medicine is concerned with primary care, natural remedies, patient education and disease prevention.

- Nosology is the classification of diseases for various purposes.

- Occupational Medicine deals with medical problems related to work and the working environment.

- Osteopathic medicine claims that much disease results from problems with bones and joints.

- Pharmacogenomics is a form of individualized medicine.

- Sports medicine deals with the treatment and preventive care of athletes, amateur and professional. The team includes specialty physicians and surgeons, athletic trainers, physical therapists, coaches, other personnel, and, of course, the athlete.

- Therapeutics is the field, more commonly referenced in earlier periods of history, of the various remedies that can be used to treat disease and promote health [2].

- Travel medicine or emporiatrics deals with health problems of international travelers or travelers across highly different environments.

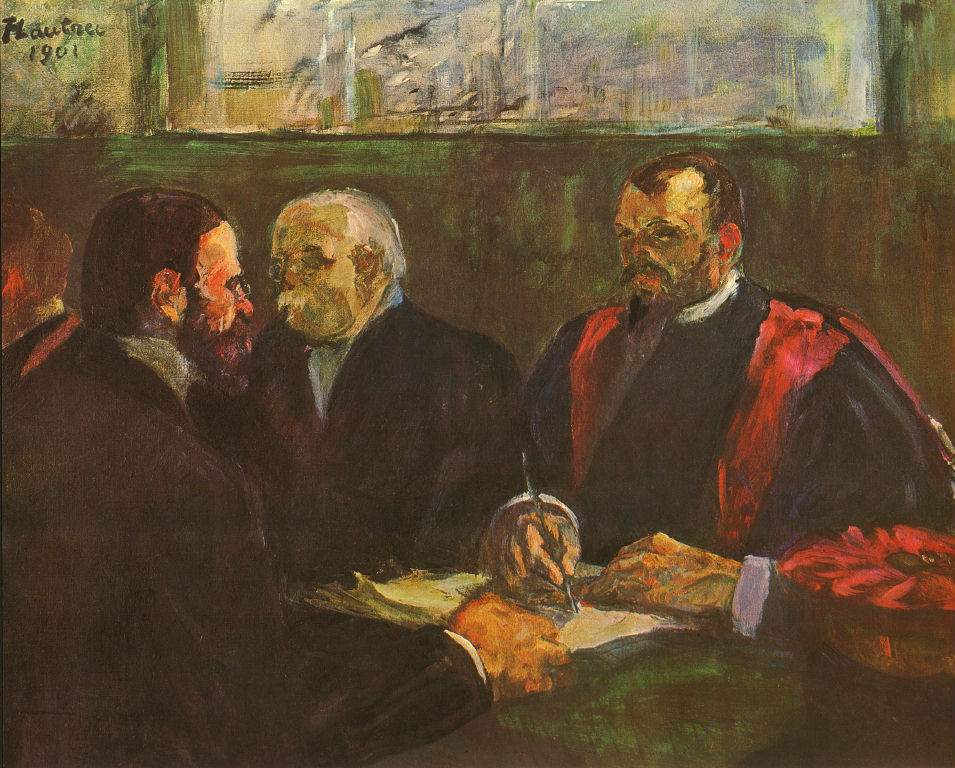

Medical education

Medical education is education connected to the practice of being a medical practitioner, either the initial training to become a physician or further training thereafter.

Medical education and training varies considerably across the world, however typically involves entry level education at a university medical school, followed by a period of supervised practice (Internship and/or Residency) and possibly postgraduate vocational training. Continuing medical education is a requirement of many regulatory authorities.

Various teaching methodologies have been utilised in medical education, which is an active area of educational research.

Presently, in England, a typical medicine course at university is 5 years (4 if the student already holds a degree). Amongst some institutions and for some students, it may be 6 years (including the selection of an intercalated BSc - taking one year - at some point after the pre-clinical studies). This is followed by 2 Foundation years afterwards, namely F1 and F2. Students register with the UK General Medical Council at the end of F1. At the end of F2, they may pursue further years of study.

In the USA, a potential medical student must first complete an undergraduate degree (Typically a BSc with a major in biology, biochemistry or medical science), before applying to a graduate medical school to pursue the M.D.

In Australia, students have two options. They can choose to take a six-year undergraduate Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) straight from high school, or complete a undergraduate degree and and then a four year Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery (BMBS) program.

Legal restrictions

In most countries, it is a legal requirement for medical doctors to be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to physicians that are trained and qualified by national standards. It is also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard against charlatans that practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based", Western, or Hippocratic Medicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health.

Criticism

Criticism of medicine has a long history. In the Middle Ages, some people did not consider it a profession suitable for Christians, as disease was often considered God-sent. God was considered to be the 'divine physician' who sent illness or healing depending on his will. However many monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, considered the care of the sick as their chief work of mercy. Barber-surgeons generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the development of academic surgery as a speciality of medicine, rather than an accessory field.

Through the course of the twentieth century, healthcare providers focused increasingly on the technology that was enabling them to make dramatic improvements in patients' health. The ensuing development of a more mechanistic, detached practice, with the perception of an attendant loss of patient-focused care, known as the medical model of health, led to further criticisms. This issue started to reach collective professional consciousness in the 1970s and the profession had begun to respond by the 1980s and 1990s.

The noted anarchist Ivan Illich heavily criticized modern medicine. In his 1976 work Medical Nemesis, Illich stated that modern medicine only medicalises disease and causes loss of health and wellness, while generally failing to restore health by eliminating disease. This medicalisation of disease forces the human to become a lifelong patient.[5]Other less radical philosophers have voiced similar views, but none were as virulent as Illich. Another example can be found in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology by Neil Postman, 1992, which criticises overreliance on technological means in medicine.

Criticism of modern medicine has led to some improvements in the curricula of medical schools, which now teach students systematically on medical ethics, holistic approaches to medicine, the biopsychosocial model and similar concepts.

The inability of modern medicine to properly address some common complaints continues to prompt many people to seek support from alternative medicine. Although most alternative approaches lack scientific validation, some may be effective in individual cases. Some physicians combine alternative medicine with orthodox approaches.

Medical errors and overmedication are also the focus of many complaints and negative coverage. Practitioners of human factors engineering believe that there is much that medicine may usefully gain by emulating concepts in aviation safety, where it was long ago realized that it is dangerous to place too much responsibility on one "superhuman" individual and expect him or her not to make errors. Reporting systems and checking mechanisms are becoming more common in identifying sources of error and improving practice.

See also

References

- ↑ Etymology: Latin: medicina, from ars medicina "the medical art," from medicus "physician."(Etym.Online) Cf. mederi "to heal," etym. "know the best course for," from PIE base *med- "to measure, limit. Cf. Greek medos "counsel, plan," Avestan vi-mad "physician")

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=medicine

- ↑ AHIMA e-HIM Work Group on the Legal Health Record. (2005). "Update: Guidelines for Defining the Legal Health Record for Disclosure Purposes". Journal of AHIMA. 78 (8): 64A&ndash, G.

- ↑ Coulehan JL, Block MR (2005). The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice (5th ed. ed.). F. A. Davis. ISBN 0-8036-1246-X.

- ↑ Ivan Illich (1976). Medical Nemesis. ISBN 0-394-71245-5 ISBN 0-7145-1095-5 ISBN 0-7145-1096-3.

External links

- NLM (US National Library of Medicine, contains resources for patients and health care professionals)

- eMedicine Physician contributed medical articles and CME

- WebMD General comprehensive online health information

- KMLE Medical Dictionary Medical dictionary and medical related links

af:Geneeskunde

als:Medizin

ar:طب

ast:Medicina

bm:Dɔkɔtɔrɔya

bn:ঔষধ

zh-min-nan:I-ha̍k

bs:Medicina

br:Medisinerezh

bg:Медицина

ca:Medicina

cv:Медицина

cs:Lékařství

da:Lægevidenskab

de:Medizin

et:Meditsiin

el:Ιατρική

eo:Medicino

eu:Medikuntza

fa:پزشکی

fy:Genêskunde

fur:Midisine

ga:Míochaine

gl:Medicina

ko:의학

hr:Medicina

io:Medicino

id:Kedokteran

ia:Medicina

iu:ᑖᒃᑎ/taakti

os:Медицинæ

is:Læknisfræði

it:Medicina

he:רפואה

csb:Medicëna

ky:Медицина

lad:Medisina

la:Medicina

lv:Medicīna

lb:Medezin

lt:Medicina

li:Genaeskónde

lo:ແພດສາດ

hu:Orvostudomány

mk:Медицина

mt:Mediċina

nl:Geneeskunde

ne:चिकित्साशास्त्र

nap:Mericina

no:Medisin

nn:Medisin

oc:Medecina

nds:Medizin

qu:Hampi yachay

sa:आयुर्विज्ञान

sq:Mjekësia

scn:Midicina

simple:Medicine

sk:Medicína

sl:Medicina

sr:Медицина

sh:Medicina

su:Tatamba

fi:Lääketiede

sv:Medicinsk vetenskap

tl:Medisina

th:แพทยศาสตร์

tg:Пизишкӣ

uk:Медицина

ur:طب

vec:Medexina

fiu-vro:Arstitiidüs

wa:Medcene