Carotid endarterectomy

|

Carotid endarterectomy |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Umar Ahmad, M.D.[2]

Overview

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is a surgical procedure used to correct carotid stenosis (narrowing of the carotid artery lumen by atheroma), used particularly when this causes medical problems, such as transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs, strokes). Endarterectomy is the removal of material on the inside (end-) of an artery. Angioplasty and stenting of the carotid artery are undergoing investigation as alternatives to carotid endarterectomy.

Introduction

Endarterectomy is a surgical procedure for removing plaque within arteries that have caused occlusion. Removal of this plaque in the carotid arteries is called Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA). Patients with blocked carotid arteries can present as symptomatic or asymptomatic. By revascularizing the arteries, blood flow can improve as well as relieve symptoms and future risks.

History

- 1946- Joao Cid dos Santos performed the first procedure on a superficial femoral artery at the University of Lisbon

- 1951- E. J. Wylie performed the first procedure of endarterectomy on an abdominal aorta. Later that same year surgeons Carrea, Molins, and Murphy repaired a carotid artery occlusion using a bypass procedure.

- 1953- First successful endarterectomy performed by Michael DeBakey at Methodist Hospital in Texas

- 1954- The Lancet journal recorded the first supposed case in medical literature by Felix Eastcott from St Mary’s Hospital in London. Although later it was realized that he only excised the diseased area and reconnected the health artery.

Indications

Surgical intervention to relieve atherosclerotic obstruction of the carotid arteries was first performed at St. Mary’s Hospital, London, in 1954. Since then, evidence for its effectiveness in different patient groups has accumulated. In 2003 nearly 140,000 carotid endarterectomies were performed in the USA (Halm).

The aim of CEA is to prevent the adverse sequelae of carotid artery stenosis secondary to atherosclerotic disease, i.e. stroke. As with any prophylactic operation, careful evaluation of the relative benefits and risks of the procedure is required on an individual patient basis. Peri-operative combined mortality and major stroke risk are 2 – 5%.

Carotid stenosis is diagnosed with ultrasound doppler studies of the neck arteries or magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA). The circle of Willis typically provides a collateral blood supply. Symptoms have to affect the other side of the body; if they do not, they may not be caused by the stenosis, and arterectomy it will be of minimal benefit.

Symptomatic Patients

The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) and the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) are both large randomized class 1 studies that have helped define current indications for carotid endarterectomy. The NASCET found that for every six patients treated, one major stroke would be prevented at two years (i.e. a “number needed to treat” (NNT) of six) for symptomatic patients with a 70 – 99% stenosis. Symptomatic patients with less severe carotid occlusion (50 – 69%) had a smaller benefit, with an NNT of 22 at five years (Barclay). In addition, co-morbidity adversely affects the outcome; patients with multiple medical problems have higher postoperative mortality and hence benefit less from the procedure.

Asymptomatic Patients

The European asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST) found that asymptomatic patients may also benefit from the procedure, but only the group with high-grade stenosis (greater than 75%). For maximum benefit, patients should be operated on soon after a TIA or stroke, preferably within the first month.

Carotid Revascularization in Patients Undergoing CABG

Symptomatic Stenosis

CEA (with embolic protection) before or concurrent with CABG is reasonable in patients with >80% stenosis who have experienced ipsilateral retinal or hemispheric cerebral ischemic symptoms within 6 months (I, C).

Asymptomatic Stenosis

The safety and efficacy of carotid revascularization before or concurrent with myocardial revacularization are not well established (II b, C)[1].

Contraindications

The procedure is not necessary when:

- There is 100% internal carotid artery obstruction because there is an increased risk of stroke and cerebral damage instead of the surgery reducing the risk.

- The person has a previous complete hemispheric stroke on the ipsilateral and complete cerebrovascular territory side with severe neurologic deficits (NIHSS>15), because there is no brain tissue at risk for further damage.

People deemed unfit for the surgery due to comorbidities.

In a more technical approach, high-risk criteria for CEA include the following:

- Age ≥80 years

- Class III/IV congestive heart failure

- Class III/IV angina pectoris

- Left main or multi vessel coronary artery disease

- Need for open heart surgery within 30 days

- Left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤30%

- Recent (≤30-day) heart attack

- Severe lung disease or COPD

- Severe renal disease

- High cervical (C2) or intrathoracic lesion

- Prior radical neck surgery or radiation therapy

- Contralateral carotid artery occlusion

- Prior ipsilateral CEA

- Contralateral laryngeal nerve injury

- Tracheostoma

Equipment

- Stethoscope: Clinical diagnosis can be achieved with the use of a stethoscope. Listening for a carotid bruit, a distinctive sound that occurs when the blood in an artery does not flow smooth as it should.

- Doppler ultrasound: This test shows the flow of blood using ultrasound waves to determine if there is an inconsistency from the normal flow.

- Study imaging: Other tests that can be done are CT scans and MRIs with the use of radioactive dyes for viewing blood flow through the arteries and

Preprocedure

Before the procedure, imaging tests such as carotid duplex ultrasonography are best used with an accuracy of 80-97% for confirming the severity of stenosis. But if on imaging less than 50% stenosis is observed then further advanced imaging is required to seek out other underlying causes. Once symptoms are correlated with the imaging, patients are prepared for anesthesia. The types of anesthesia are general anesthesia and regional anesthesia. Of both types, regional anesthesia is preferred. This is to observe for any intraoperative complications such as cerebral ischemia. On the other hand, general anesthesia is done to reduce the anxiety of the patient and making reentry of the internal carotids smoother. Although the type of anesthesia the patient is put under does not have a significant impact on the outcome of surgery, regional anesthesia reduces the operating time, and the time to recovery. While being prepared patients are not required to stop any particular medications but instead, they are encouraged to continue taking antiplatelet therapies and blood pressure medications for the prevention of clotting risks and maintaining optimal blood pressures. After the patient is prepared, they are then placed in a supine position with the head of the patient turned away from the side of surgery. This allows for a wider field to work with. The area is then sterilized, draped, and lighted.

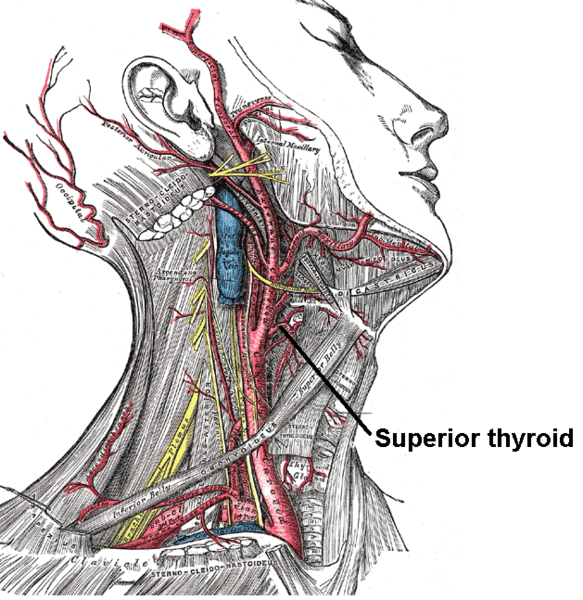

Procedure

Conventional CEA

The internal, common and external carotid arteries are clamped, the lumen of the internal carotid artery is opened, and the atheromatous plaque substance removed. The artery is closed, hemostasis achieved, and the overlying layers closed. Many surgeons lay a temporary shunt to ensure blood supply to the brain during the procedure. The procedure may be performed under general or local anesthesia. The latter allows for direct monitoring of neurological status by intra-operative verbal contact and testing of grip strength. With general anesthesia, indirect methods of assessing cerebral perfusion must be used, such as electroencephalography (EEG), transcranial doppler analysis and carotid artery stump pressure monitoring. At present, there is no good evidence to show any major difference in outcome between local and general anesthesia.

Non-invasive procedures have been developed, by threading catheters through the femoral artery, up through the aorta, then inflating a balloon to dilate the carotid artery, with or without a wire-mesh shunt. The safety and effectiveness of these procedures are controversial. In the SAPPHIRE study, Yadav concluded that this procedure, known as carotid stenting, was non-inferior to carotid endarterectomy in total adverse events, and lowered event rates for major stroke, cranial nerve palsy, and myocardial infarction, in patients at high risk for surgery.[2] However, Cambria concluded that the study was not sufficiently powered to detect differences in stroke and death, and final conclusions must await larger trials.[3]

Eversion CEA

Postprocedure

After the surgery is complete, the patient is awakened from anesthesia and neurological deficits are ruled out. From there on the patient is sent to the recovery room where they are monitored for 6 hours. During these 6 hours, careful observation is given to neurologic deterioration, blood pressure and bleeding.

Medications

Common medications taken are antidysrhythmic agents, anticoagulants, and antiplatelets. Antidysrhythmic agents such as 1% Lidocaine Hydrochloride are given to reverse carotid reflex bradycardia. Anticoagulants such as Heparin are given to reduce the thrombotic events. Antiplatelets such as Aspirin and Clopidogrel are given to prevent ischemic strokes. Unless contraindicated, Aspirin is preferred over Clopidogrel.

Special Situations

- Bilateral carotid stenosis – Unilateral CEA of any vessel in bilateral occlusion leads to increased complications. This led to the NASCET study which further concluded that ipsilateral stenosis and contralateral occlusion augmented the risk for stroke. In all cases, the treatment of symptomatic patients with CEA had better outcomes over medication and is more effective than CAS.

- Prophylactic carotid endarterectomy – Prophylactic CEA is generally considered in patients who have previously undergone coronary artery bypass grafts (CABGs) or major peripheral vascular procedures.

Complications

- Hypotension

- Hypertension

- Horner syndrome

- Wound hematoma

- Injury to Facial nerve

- Injury to Vagus nerve

- Cranial nerve dysfunction

- Injury to Hypoglossal nerve

- Infection and false aneurysm

- Injury to Glossopharyngeal nerve

- Hyperperfusion and cerebral hemorrhage

Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Selection of Patients for Carotid Revascularization[4]

| Class I |

| "1. Patients at average or low surgical risk who experience nondisabling ischemic stroke† or transient cerebral ischemic symptoms, including hemispheric events or amaurosis fugax, within 6 months (symptomatic patients) should undergo CEA if the diameter of the lumen of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery is reduced more than 70%‡ as documented by noninvasive imaging (Level of Evidence: A) or more than 50% as documented by catheter angiography (Level of Evidence: B) and the anticipated rate of perioperative stroke or mortality is less than 6%. " |

| "2. CAS is indicated as an alternative to CEA for symptomatic patients at average or low risk of complications associated with endovascular intervention when the diameter of the lumen of the internal carotid artery is reduced by more than 70% as documented by noninvasive imaging or more than 50% as documented by catheter angiography and the anticipated rate of periprocedural stroke or mortality is less than 6%. (Level of Evidence: B). " |

| "3. Selection of asymptomatic patients for carotid revascularization should be guided by an assessment of comorbid conditions, life expectancy, and other individual factors and should include a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure with an understanding of patient preferences. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class III (No Benefit) |

| "1. Except in extraordinary circumstances, carotid revascularization by either CEA or CAS is not recommended when atherosclerosis narrows the lumen by less than 50%. (Level of Evidence: A) " |

| "2. Carotid revascularization is not recommended for patients with chronic total occlusion of the targeted carotid artery. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "3. Carotid revascularization is not recommended for patients with severe disability caused by cerebral infarction that precludes preservation of useful function. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIa |

"1. It is reasonable to perform CEA in asymptomatic patients who have more than 70% stenosis of the internal carotid artery if the risk of perioperative stroke, MI, and death is low. (Level of Evidence: A)

|

| "2. It is reasonable to choose CAS over CEA when revascularization is indicated in patients with neck anatomy unfavorable for arterial surgery. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "3. When revascularization is indicated for patients with TIA or stroke and there are no contraindications to early revascularization, intervention within 2 weeks of the index event is reasonable rather than delaying surgery. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1. Prophylactic CAS might be considered in highly selected patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis (minimum 60% by angiography, 70% by validated Doppler ultrasound), but its effectiveness compared with medical therapy alone in this situation is not well established. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "2. In symptomatic or asymptomatic patients at high risk of complications for carotid revascularization by either CEA or CAS because of comorbidities, the effectiveness of revascularization versus medical therapy alone is not well established. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

Outcome

- Shown below is a summary table depicting the risk of stroke following medical treatment versus CEA according to different studies.[1]

| Stroke Risk (%) | |||||

| Trial | % Stenosis | n | Follow up (year) | Medical | Surgical |

| NASCET | 70-90 | 659 | 1.5 | 25 | 9 |

| ECST | 70-90 | 778 | 3 | 16.8 | 10.3 |

| NASCET | 50-69 | 1108 | 5 | 16.2 | 11.3 |

| ACAS | >60 | 1662 | 2.7 | 11 | 5.1 |

| ECST | >60 | 3120 | 3.4 | 11 | 3.8 |

Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Periprocedural Management of Patients Undergoing Carotid Endarterectomy[4]

| Class I |

| "1. Aspirin (81 to 325 mg daily) is recommended before CEA and may be continued indefinitely postoperatively. (Level of Evidence: A) " |

| "2. Beyond the first month after CEA, aspirin (75 to 325 mg daily), clopidogrel (75 mg daily), or the combination of low-dose aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole (25 and 200 mg twice daily, respectively) should be administered for long-term prophylaxis against ischemic cardiovascular events. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "3. Administration of antihypertensive medication is recommended as needed to control blood pressure before and after CEA. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "3. The findings on clinical neurological examination should be documented within 24 hours before and after CEA. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIa |

| "1. Patch angioplasty can be beneficial for closure of the arteriotomy after CEA.62,63 (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "2. Administration of statin lipid-lowering medication for prevention of ischemic events is reasonable for patients who have undergone CEA irrespective of serum lipid levels, although the optimum agent and dose and the efficacy for prevention of restenosis have not been established. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "3. Noninvasive imaging of the extracranial carotid arteries is reasonable 1 month, 6 months, and annually after CEA to assess patency and exclude the development of new or contralateral lesions. Once stability has been established over an extended period, surveillance at longer intervals may be appropriate. Termination of surveillance is reasonable when the patient is no longer a candidate for intervention. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Management of Patients Experiencing Restenosis After Carotid Endarterectomy or Stenting[4]

| Class III (No Benefit) |

| "1. Reoperative CEA or CAS should not be performed in asymptomatic patients with less than 70% carotid stenosis that has remained stable over time. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIa |

| "1. In patients with symptomatic cerebral ischemia and recurrent carotid stenosis due to intimal hyperplasia or atherosclerosis, it is reasonable to repeat CEA or perform CAS using the same criteria as recommended for initial revascularization. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| "2. Reoperative CEA or CAS after initial revascularization is reasonable when duplex ultrasound and another confirmatory imaging method identify rapidly progressive restenosis that indicates a threat of complete occlusion. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1. In asymptomatic patients who develop recurrent carotid stenosis due to intimal hyperplasia or atherosclerosis, reoperative CEA or CAS may be considered using the same criteria as recommended for initial revascularization. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA) vs Stenting (CAS)

- The CREST study showed a higher rate of death/MI in patients treated with stenting vs CEA: 6.4% vs 4.7%.

- CEA is preferred in patients who impaired renal function who are at risk of contrast induced nephropathy, tortuous calcified aortas, complex eccentric calcified lesions.

- Stenting may be preferred in patients with high carotid bifurcations where it is hard for surgeons to technically perform the surgery.

- If an elderly patient has a transient ischemic attack and if there is a narrowing in the ipsilateral artery, then carotid endarterectomy should be performed within two weeks of the symptoms.

- CAS is considered over CEA in patients with neck anatomy unfavorable for arterial surgery(II a, B):

- Arterial stenosis distal to the second cervical vertebra or proximal (intrathoracic) arterial stenosis

- Previous ipsilateral CEA

- Contralateral vocal cord paralysis

- Open tracheostomy

- Radical surgery

- Irradiation.[1].

- Shown below is a table comparing carotid endarterectomy versus stenting in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients[1].

| Symptomatic Patients | Asymptomatic Patients | ||

| 50-69% Stenosis | 70-99% Stenosis | 70-99% Stenosis | |

| Endarterectomy | Class I | Class I | Class II a |

| LOE | B | A | A |

| Stenting | Class I | Class I | Class II b |

| LOE | B | B | B |

Related Chapters

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline.Circulation.2011;124:e54-e130

- ↑ Yadav et al., Protected Carotid Artery Stenting versus Endarterectomy in High-Risk Patients, N Engl J Med . 2004 October 7;351:1493-1501 PMID 15470212.

- ↑ Cambria RP. Stenting for carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 7;351:1565-7. PMID 15470220

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, Bacharach JM, Barr JD, Bush RL; et al. (2011). "2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery". Circulation. 124 (4): 489–532. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820d8d78. PMID 21282505.