Shigella

|

Shigellosis Microchapters |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Shigella On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Shigella |

| Shigella | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

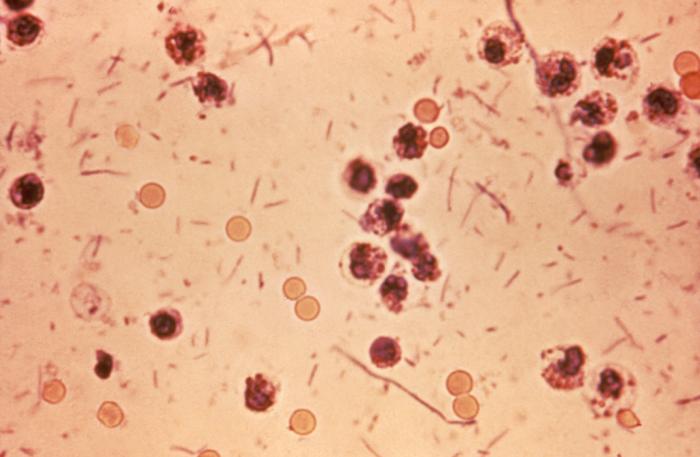

Photomicrograph of Shigella sp. in a stool specimen

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

Template:Seealso Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Shigella is a genus of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, nonspore-forming, nonmotile, rod-shaped bacteria closely related to Salmonella. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who first discovered it in 1897.[1]

The causative agent of human shigellosis, Shigella causes disease in primates, but not in other mammals.[2][page needed] It is only naturally found in humans and apes.[3][4] During infection, it typically causes dysentery.[5] Shigella is one of the leading bacterial causes of diarrhea worldwide. Insufficient data exist, but conservative estimates suggest Shigella causes about 90 million cases of severe dysentery, with at least 100,000 of these resulting in death each year, mostly among children in the developing world.[6]

Classification

Shigella species are classified by four serogroups:

- Serogroup A: S. dysenteriae (15 serotypes)[7]

- Serogroup B: S. flexneri (six serotypes)

- Serogroup C: S. boydii (19 serotypes)[8]

- Serogroup D: S. sonnei (one serotype)

Groups A–C are physiologically similar; S. sonnei (group D) can be differentiated on the basis of biochemical metabolism assays.[9] Three Shigella groups are the major disease-causing species: S. flexneri is the most frequently isolated species worldwide, and accounts for 60% of cases in the developing world; S. sonnei causes 77% of cases in the developed world, compared to only 15% of cases in the developing world; and S. dysenteriae is usually the cause of epidemics of dysentery, particularly in confined populations such as refugee camps.[6]

Each of the Shigella genomes includes a virulence plasmid that encodes conserved primary virulence determinants. The Shigella chromosomes share most of their genes with those of E. coli K12 strain MG1655.[10] Phylogenetic studies indicate Shigella is more appropriately treated as subgenus of Escherichia, and that certain strains generally considered E. coli – such as E. coli O157:H7 – are better placed in Shigella.

Pathogenesis

Shigella infection is typically by ingestion (fecal–oral contamination); depending on age and condition of the host, fewer than 100 bacterial cells can be enough to cause an infection.[11] Shigella causes dysentery that results in the destruction of the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa in the cecum and rectum. Some strains produce the enterotoxin shiga toxin, which is similar to the verotoxin of E. coli O157:H7[9] and other verotoxin-producing E. coli. Both shiga toxin and verotoxin are associated with causing hemolytic uremic syndrome. As noted above, these supposed E. coli strains are at least in part actually more closely related to Shigella than to the "typical" E. coli.

Shigella species invade the host through the M-cells interspersed in the gut epithelia of the small intestine, as they do not interact with the apical surface of epithelial cells, preferring the basolateral side.[12] Shigella uses a type-III secretion system, which acts as a biological syringe to translocate toxic effector proteins to the target human cell. The effector proteins can alter the metabolism of the target cell, for instance leading to the lysis of vacuolar membranes or reorganization of actin polymerization to facilitate intracellular motility of Shigella bacteria inside the host cell. For instance, the IcsA effector protein triggers actin reorganization by N-WASP recruitment of Arp2/3 complexes, helping cell-to-cell spread.

After invasion, Shigella cells multiply intracellularly and spread to neighboring epithelial cells, resulting in tissue destruction and characteristic pathology of shigellosis.[13][14]

The most common symptoms are diarrhea, fever, nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, and flatulence. It is also commonly known to cause large and painful bowel movements. The stool may contain blood, mucus, or pus. Hence, Shigella cells may cause dysentery. In rare cases, young children may have seizures. Symptoms can take as long as a week to appear, but most often begin two to four days after ingestion. Symptoms usually last for several days, but can last for weeks. Shigella is implicated as one of the pathogenic causes of reactive arthritis worldwide.[15]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of shigellosis is made by isolating the organism from diarrheal fecal sample cultures. Shigella species are negative for motility and are generally not lactose fermenters, but S. sonnei can ferment lactose.[16] They typically do not produce gas from carbohydrates (with the exception of certain strains of S. flexneri) and tend to be overall biochemically inert. Shigella should also be urea hydrolysis negative . When inoculated to a triple sugar iron (TSI) slant, they react as follows: K/A, gas -, and H2S -. Indole reactions are mixed, positive and negative, with the exception of S. sonnei, which is always indole negative. Growth on Hektoen enteric agar will produce bluish-green colonies for Shigella and bluish-green colonies with black centers for Salmonella.

Prevention and treatment

Hand washing before handling food and thoroughly cooking all food before eating decreases the risk of getting shigellosis.[17]

Severe dysentery can be treated with ampicillin, TMP-SMX, or fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, and of course rehydration. Medical treatment should only be used in severe cases or for certain populations with mild symptoms (elderly, immunocompromised, food service industry workers, child care workers). Antibiotics are usually avoided in mild cases because some Shigella species are resistant to antibiotics, and their use may make the bacteria even more resistant. Antidiarrheal agents may worsen the sickness, and should be avoided.[18] For Shigella-associated diarrhea, antibiotics shorten the length of infection.[19]

Currently, no licenced vaccine targeting Shigella exists. Shigella has been a longstanding World Health Organization target for vaccine development, and sharp declines in age-specific diarrhea/dysentery attack rates for this pathogen indicate natural immunity does develop following exposure; thus, vaccination to prevent the disease should be feasible. Several vaccine candidates for Shigella are in various stages of development.[6]

Also extensive research has been conducted into therapies, involving treatment with bacteriophages, as described in.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Yabuuchi E. (2002). Bacillus dysentericus (sic) 1897 was the first rather than Bacillus dysenteriae 1898. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 52, 1041-1041

- ↑ Ryan, Kenneth James; Ray, C. George, ed. (2004). Sherris medical microbiology: an introduction to infectious diseases (4 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional Med/Tech. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ Template:Cite doi

- ↑ http://www.eaza.net/activities/tdfactsheets/094%20Shigellosis.doc.pdf

- ↑ Mims, Playfair, Roitt, Wakelin, Williams (1993). Medical Microbiology (1st ed.). Mosby. p. A.24. ISBN 0-397-44631-4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Diarrhoeal Diseases: Shigellosis". Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR). World Health Organization. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ Ansaruzzaman M., Kibriya A.K.M.G., Rahman A., Neogi P.K.B., Faruque A.S.G., Rowe B., Albert M.J. (1995). Detection of provisional serovars of Shigella dysenteriae and designation as S. dysenteriae serotypes 14 and 15. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1423–1425

- ↑ Yang Z., Hu C., Chen J., Chen G., Liu Z. (1990). A new serotype of Shigella boydii. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao.; 30(4): 284-95

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hale, Thomas L.; Keusch, Gerald T. (1996). "Shigella: Structure, Classification, and Antigenic Types". In Baron, Samuel. Medical microbiology (4 ed.). Galveston, Texas: University of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Yang, Fan; Yang, J; Zhang, X; Chen, L; Jiang, Y; Yan, Y; Tang, X; Wang, J; Xiong, Z; Dong, J; Xue, Y; Zhu, Y; Xu, X; Sun, L; Chen, S; Nie, H; Peng, J; Xu, J; Wang, Y; Yuan, Z; Wen, Y; Yao, Z; Shen, Y; Qiang, B; Hou, Y; Yu, J; Jin, Q (2005). "Genome dynamics and diversity of Shigella species, the etiologic agents of bacillary dysentery" (PDF). Nucleic Acids Research. 33 (19): 6445–6458. doi:10.1093/nar/gki954. PMC 1278947. PMID 16275786. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Levinson, Warren E (2006). Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology (9 ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-07-146031-6. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Mounier, Joëlle; Vasselon, T; Hellio, R; Lesourd, M; Sansonetti, PJ (January 1992). "Shigella flexneri Enters Human Colonic Caco-2 Epithelial Cells through the Basolateral Pole". Infection and Immunity. 60 (1): 237–248. PMC 257528. PMID 1729185.

- ↑ http://textbookofbacteriology.net/Shigella_2.html

- ↑ http://iai.asm.org/content/69/10/5959.full

- ↑ Hill Gaston, J.S; Lillicrap, Mark S (April 2003). "Arthritis associated with enteric infection". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 17 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00104-3. PMID 12787523.

- ↑ Ito H, Kido N, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Sugiyama T, Kato N; Kido; Arakawa; Ohta; Sugiyama; Kato (October 1991). "Possible mechanisms underlying the slow lactose== fermentation phenotype in Shigella spp". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 57 (10): 2912–2917. PMC 183896. PMID 1746953. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Ram, PK; Crump JA; Gupta SK; Miller MA; Mintz ED (2008). "Analysis of Data Gaps Pertaining to Shigella Infections in Low and Medium Human Development Index Countries, 1984-2005". Epidemiology and Infection. 136 (5): 577–603. doi:10.1017/S0950268807009351. PMC 2870860. PMID 17686195.

- ↑ "How can Shigella infections be treated?". Shigellosis: General Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Christopher, Prince RH; David, Kirubah V; John, Sushil M; Sankarapandian, Venkatesan (2010). Christopher, Prince RH, ed. "Antibiotic therapy for Shigella dysentery" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD006784. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006784.pub4. PMID 20687081. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Lawrence D. Goodridge (2013-01-01). "Bacteriophages for managing Shigella in various clinical and non-clinical settings". Bacteriophage. 3 (1). doi:10.4161/bact.25098. PMID 23819110.

External links

- Shigella genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- World Health Organization: Shigella

- "Shigella Datasheet" (PDF). New Zealand Food Safety Authority. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Vaccine Resource Library: Shigellosis and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)