Sandbox:Retropharyngeal abscess: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

* Radiopaque foreign body | * Radiopaque foreign body | ||

* Soft-tissue mass | * Soft-tissue mass | ||

[[File:Retropharyngeal abscess..png|center|frameless| | [[File:Retropharyngeal abscess..png|center|frameless|316x316px|link=http://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/File:Retropharyngeal_abscess..png]]'''CT scan''' | ||

Patients with retropharyngeal abscess, abscess may appear as | Patients with retropharyngeal abscess, abscess may appear as | ||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

MANAGEMENT | MANAGEMENT | ||

There are no comprehensive randomized controlled studies evaluating the management of retropharyngeal infections. | |||

Overview of strategy — Randomized controlled trials evaluating management of retropharyngeal infections are lacking. Recommendations for treatment are based upon the causative pathogens and response to therapy described in observational studies [4,14,36,41-46]. | Overview of strategy — Randomized controlled trials evaluating management of retropharyngeal infections are lacking. Recommendations for treatment are based upon the causative pathogens and response to therapy described in observational studies [4,14,36,41-46]. | ||

Revision as of 15:01, 14 February 2017

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Vishal Devarkonda, M.B.B.S[2]

Synonyms and keywords:

Overview

Historical Perspective

Classification

There is no established classification system for retropharyngeal abscess.

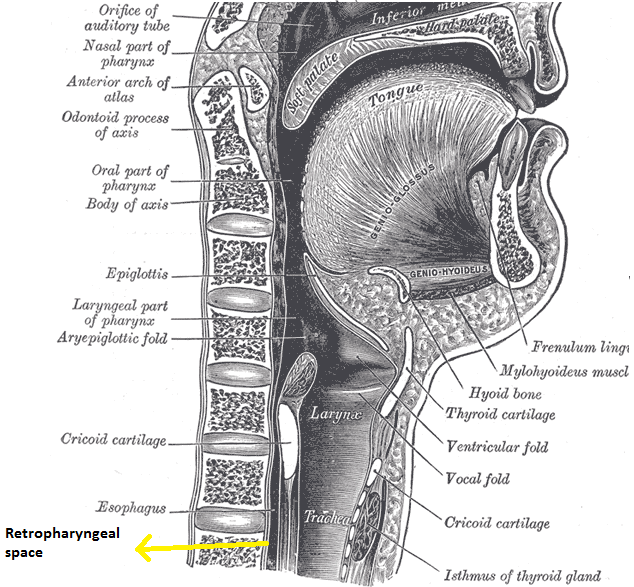

Pathophysiology

Retropharyngeal space is a deep space in neck extending from the base of skull to the posterior mediastinum. Space is bordered anteriorly by middle layer of the deep cervical fascia(buccopharyngeal fascia), posteriorly by deep layer of deep cervical fascia, laterally by the carotid sheath which contain carotid arte ry and jugular vein.

The pathophysiology of retropharyngeal abscess can be discussed in following headings:

Transmission

Transmission of the infection to the retropharyngeal space could be by trauma, lymphatic spread or by direct spread.

| Mode of transmission of infection to retropharyngeal space | |

|---|---|

| Lymphatic spread | Retropharyngeal space consists two pair of lymphnodes, which drains nasopharynx, adenoids, posterior paranasal sinuses, middle ear, and eustachian tube. Draining infected can be infected following the upper respiratory tract infection. Lymphnode may undergo liquefaction necrosis, which my progress into retropharyngeal cellulitis, which left intreated can progress to abcess formation. However by age 4 years, these lymph node undergo spontaneous atrophy. |

| Direct spread/ Trauma | Adults

In adults, retropahryngeal space can be contaminated by direct trauma(eg, penetrating foreign trauma, endoscopy, dental procedures) or extension of local infection such as odontogenic infection, ludwig's angina, or osteomyelitis of cervical spine Children In children, retropahryngeal space can be contaminated by direct trauma( to oropharynx(swallowing a foreign body or running and falling with an object in the mouth). |

Microbiology

Polymicrobial infection is often responsible for retropharyngeal abscess. The other predominant species involved in causes in retropharyngeal abscess include:

- Beta-hemolytic streptococcus

- Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus [GAS])

- Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]),

- Fusobacteria

- Prevotella

- Veillonella

- Haemophilus Influenzae

- Neisseria species

- Bacteroides

- Fusoabcterium

- Salmonella

Infections in these areas may lead to suppurative adenitis of the retropharyngeal lymph nodes [1,2,5,6]. Retropharyngeal abscess is associated with antecedent upper respiratory tract infection in approximately one-half of cases [7].

In approximately one-fourth of cases (usually in older children or adults), retropharyngeal infection is secondary to pharyngeal trauma (eg, penetrating foreign body, endoscopy, intubation attempt, dental procedures) [1,5,7-11]. It also may occur in association with pharyngitis, vertebral body osteomyelitis, and petrositis.

Retropharyngeal infections progress from cellulitis to organized phlegmon to mature abscess [1]. Early institution of appropriate antimicrobial therapy may halt progression to mature abscess [12].

Immune response

Retropharyngeal infections progress from cellulitis to organized phlegmon to mature abscess [1]. Early institution of appropriate antimicrobial therapy may halt progression to mature abscess

Epidemiology and Demographics

Screening

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural history

Complications

Complications of retropharyngeal abscess include:

- Epidural abscess

- Mediastinitis

- Carotid artery aneurysm or erosion

- Internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis

- Septic pulmonary embolism

- Cranial nerve dysfunction (IX–XII)

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Life-threatening descending necrotizing mediastinitis

- Sepsis

Prognosis

The prognosis of retropharyngeal abscess is good when detected early and appropriately treated. Relapse may occur in 1 to 5 percent of cases

Diagnosis

History and symptoms

Patients with retropharyngeal abscess may present with:

- Pain in neck

- Fever

- Sore throat

- Mass in neck

- Respiratory distress(stridor)

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Pain with swallowing (odynophagia)

- Unwillingness to move the neck(torticollis)

- Change in voice

- reduced opening of the jaws(Trismus)

- Chest pain

Physical examination

Role of physical examination in diagnosing the retro pharyngeal abscess is limited, as most of the patients aren't able to open the mouth widely.

Patients with suspected retropharyngeal abscess should be examined in a head-down position(trendelenburg) position. It is recommended to perform examination in operation room as it permits to place an aritifical airway if necessary. A midline or unilateral swelling of the posterior pharyngeal wall can be appreciated.

Other physical examination findings include

- Tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy

- Palpable neck mass

Laboratory findings

Laboratory findings may show non-specific leukocytosis.

Imaging

Diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess should be ultimately supported by radiographic imaging. In suspected patients, an initial lateral and anterio-posterior X-ray of neck should be ordered, which is usually followed with CT scan of the neck with IV contrast. Ct scan not only helps in diagnosing the retropharyngeal abscess but also helps in identifying the position of carotid artery and internal jugular vein in relation to the infectious process.

Plain X-ray

Lateral neck X ray demonstrate thickening of soft tissue with possible gas-fluid levels in the pre-vertebral cervical space.

Pathological widening of retropharyngeal space should be considered if it is greater than 22 mm at C6 in adults and 7 mm at C2 or 14 mm at C6 in children.

Other X ray findings include:

- Reversal of the normal cervical lordosis

- Radiopaque foreign body

- Soft-tissue mass

CT scan

Patients with retropharyngeal abscess, abscess may appear as

- Mass impinging on the posterior pharyngeal wall

- Complete rim enhancement with scalloping is indicative of an abscess

- Low density core, soft tissue swelling, obliterated fat planes are other common CT scan associated with retropharyngeal abscess

Treatment

MANAGEMENT

There are no comprehensive randomized controlled studies evaluating the management of retropharyngeal infections.

Overview of strategy — Randomized controlled trials evaluating management of retropharyngeal infections are lacking. Recommendations for treatment are based upon the causative pathogens and response to therapy described in observational studies [4,14,36,41-46].

Children with suspected retropharyngeal infection should be hospitalized and managed in consultation with an otolaryngologist [23,47]. Particular attention must be paid to maintenance of the airway. Intubation, or less commonly, tracheotomy may be necessary in patients with respiratory compromise [1,47].

Initial therapy depends upon the severity of respiratory distress and likelihood of drainable fluid (based upon CT findings, and clinical features such as duration of symptoms and clinical course):

●Immediate surgical drainage is necessary in patients with airway compromise. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as is possible. (See 'Surgical drainage' below and 'Antimicrobial therapy' below.)

●Early in the disease process (cellulitis or phlegmon), antimicrobial therapy may prevent progression, precluding the need for surgery [1,7,41]. (See 'Antimicrobial therapy' below.)

●We suggest that children with retropharyngeal abscesses and no airway compromise receive a trial of antibiotic therapy for 24 to 48 hours without surgical drainage, especially if the CT findings are not consistent with a mature abscess that is greater than 3 cm2 [4,34,42]. (See 'Antimicrobial therapy' below.)

The optimal management of retropharyngeal abscess in patients without imminent airway obstruction is a matter of debate [6,48]. Some experts advocate immediate drainage in conjunction with antimicrobial therapy [35]. Others favor a trial of antimicrobial therapy for 24 to 48 hours, especially in patients with small abscesses (eg, cross-sectional area <2 to 3 cm2) [4,14,34,41-46].

Factors that have been associated with drainable fluid at surgery include duration of symptoms for more than two days, and cross-sectional area >2 cm2 on CT scan [6]. Although it was thought that early surgical drainage in such patients would shorten the length of stay in the hospital and reduce cost of treatment [6], limited evidence does not support this hypothesis. As an example, in an observational study of 111 children with retropharyngeal abscesses, surgical drainage (73 children) was associated with greater cost and similar lengths of stay when compared to children treated with intravenous antibiotics alone [48].

Children with retropharyngeal infections must be monitored closely for persistence or progression of symptoms and complications. (See 'Complications' below.)

Supportive care — Supportive care for the child with retropharyngeal infection includes maintenance of the airway, adequate hydration, provision of analgesia, and monitoring for complications [23]. Patients with an unstable airway should be monitored in the intensive care unit; endotracheal intubation may be necessary for airway maintenance.

Antimicrobial therapy — Antimicrobial therapy is a necessary component of the treatment of retropharyngeal infections in children. In the pre-antibiotic era, the mortality rates for deep neck space infections in children ranged from 7 to 15 percent and complications occurred in as many as 25 percent [4]. With the advent of antibiotic therapy, mortality and complications are uncommon.

Successful treatment of suppurative retropharyngeal infection with antimicrobial therapy alone has been reported in observational studies [4,14,34,41,42,46,48]. Success rates in retrospective series range from 37 to 75 percent [14,34,42]. In a small prospective series, 10 of 11 children with suppurative deep neck infections greater than 1 cm3 responded to antibiotic therapy without developing complications [4].

Potential risks of nonsurgical management include spontaneous rupture, respiratory distress requiring intubation or temporary tracheostomy, and longer hospital stay [6,45,49].

Empiric therapy — Empiric therapy should include coverage for Group A Streptococcus, S. aureus and respiratory anaerobes. Empiric therapy can be amended as necessary based upon culture results if drainage is performed or clinical response to treatment. When tailoring therapy based upon culture results, it is important to bear in mind that retropharyngeal infections are frequently polymicrobial, and not all microbes are consistently cultured [25]. (See 'Microbiology' above.)

Empiric regimens include [1]:

●Ampicillin-sulbactam (50 mg/kg per dose every six hours intravenously), or

●Clindamycin (15 mg/kg per dose [maximum single dose 900 mg]every eight hours intravenously)

However, ampicillin-sulbactam does not provide antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and, depending upon local susceptibility patterns, clindamycin may not be active against Group A streptococcus [50], methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, and/or MRSA. (See "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children: Treatment of invasive infections", section on 'Clindamycin'.)

Accordingly, in patients who do not respond to initial treatment with the empiric regimens above or who present with moderate or severe disease, intravenous vancomycin or linezolid should be added to empiric treatment with either ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin to provide optimal coverage for potentially-resistant Gram-positive cocci.

●Vancomycin (40 to 60 mg/kg per day divided in three to four doses; maximum daily dose 2 to 4 g), or

●Linezolid (<12 years: 30 mg/kg per day divided in three doses; ≥12 years: 20 mg/kg per day in two doses; maximum daily dose 1200 mg) (see "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children: Treatment of invasive infections", section on 'Treatment approach' and "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children: Epidemiology and clinical spectrum", section on 'CA-MRSA strains')

Parenteral treatment is maintained until the patient is afebrile and clinically improved. Oral therapy should be continued to complete a 14-day course. Appropriate oral regimens for continuation of therapy include:

●Amoxicillin-clavulanate (45 mg/kg per dose every 12 hours), or

●Clindamycin (13 mg/kg per dose every 8 hours)

When vancomycin has been added to the parenteral regimen, linezolid may be used for oral therapy.

Response to therapy — Response to antimicrobial therapy is indicated by improvement in symptoms and defervescence [1,45,46]. CT with contrast should be performed if there is no clinical improvement 24 to 48 hours after initiation of antibiotic therapy [1,41].

Treatment failure is defined by lack of symptomatic improvement or worsening despite 24 to 48 hours of antimicrobial therapy (with or without surgical drainage). Treatment failure may occur in patients who have developed complications, are infected with unusual organisms, or have underlying problems (eg, congenital cyst or tract) [25]. Reevaluation of such patients may include repeat imaging (CT with contrast to look for extension of infection) or surgical intervention. Broadening antimicrobial therapy to cover MRSA and gram-negative rods also may be indicated.

Surgical drainage — Surgical drainage in conjunction with antibiotic therapy has played a prominent role in the management of retropharyngeal abscess.

Indications for surgical drainage may include [6,14,43]:

●Airway compromise or other life-threatening complications

●A large (>3 cm2) hypodense area on CT scan that is consistent with a mature abscess (complete rim enhancement and scalloping)

●Failure to respond to parenteral antibiotic therapy

If surgical drainage is performed, specimens for aerobic and anaerobic culture should be obtained [1].

Surgical drainage is usually performed trans-orally unless the abscess is lateral to the neck vessels or involves multiple deep neck space infections [1,6,37]. A second procedure may be required in a minority of cases [6,24]. Complications related to surgical drainage are rare.

Discharge instructions — Patients who are discharged from the hospital after treatment for retropharyngeal infection should be instructed that prompt reevaluation is necessary for the following symptoms [25]:

●Dyspnea

●Worsening throat pain, neck pain, or trismus

●Enlarging mass

●Fever

●Neck stiffness

Follow-up should be arranged within several days of discharge.

General measures

Good hygiene which include retracting the foreskin regularly and gentle cleansing of entire glans, preputial sac, and foreskin were found effective in treating the diseases.