Rhabdomyoma

|

WikiDoc Resources for Rhabdomyoma |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Rhabdomyoma Most cited articles on Rhabdomyoma |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Rhabdomyoma |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Rhabdomyoma at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Rhabdomyoma at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Rhabdomyoma

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Rhabdomyoma Discussion groups on Rhabdomyoma Patient Handouts on Rhabdomyoma Directions to Hospitals Treating Rhabdomyoma Risk calculators and risk factors for Rhabdomyoma

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Rhabdomyoma |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Nima Nasiri, M.D.[2] Simrat Sarai, M.D. [3]

Synonyms and keywords: Rhabdomyomatous neoplasm; Adult rhabdomyoma; Genital rhabdomyoma; Fetal rhabdomyoma

Overview

A rhabdomyoma is a benign tumor of striated muscle. Rhabdomyomas develop mostly before the age of one year, almost exclusively in children, and approximately 80 to 90 percent are associated with tuberous sclerosis.[1][2] The most common primary benign pediatric tumor of the heart is cardiac rhabdomyoma which can be seen mainly in fetal life and children.Second most common primary benign cardiac tumor in children is fibroma.[3][4]

Classification

- Rhabdomyoma may be classified into the following subtypes: [5]

- Neoplastic

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma

- Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas of the skin

Staging

The staging of rhabdomyomas is based on the grade (G), site (T), and metastasis (M), as follows:

- G0 - Benign

- T0 - Intracapsular

- T1 - Extracapsular, intracompartmental

- M0 - None

| Stage | Severity | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- Cardiac rhabdomyomas tend to grow up to approximately 32 weeks gestation. After, cells usually lose their ability to divide and undergo apoptosis via a ubiquitin-mediated pathway. The degradation of myofilaments is expressed by ubiquitin. Apoptosis follows, leading to the eventual regression of the hamartoma. Complete or partial resolution occurs in the majority of cases, regardless of the initial size of the tumor.

Location

- Approximately 90% of adult rhabdomyoma are found in head and neck.[6]

- Adult rhabdomyoma is localized to the oropharynx, the larynx, and the muscles of the neck.

- Fetal rhabdomyoma occurs most often in the subcutaneous tissues of the head and neck in children.

- Genital rhabdomyoma most often involves the vagina or vulva.

- Location of cardiac rhabdomyoma determines the clinical presentation, it usually involves the myocardium of both ventricles and the interventricular septum, but can be found in the atria, the epicardial surface, or the cavoatrial junction.

Immunohistochemistry

- Cross-striation has been demonstrated by muscle specific actin, phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH), desmin, and myoglobin.

- Dystrophin is shown to be expressed in the cell membranes.

Associated Conditions

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma is associated with a variety of abnormalities such as :

- Tuberous sclerosis (most common associated genetical abnormality)

- Brain lesions

- Down syndrome

- Ebstein anomaly

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

Gross Pathology

- On gross pathology, round or polypoid mass in the region of the neck are characteristic findings of adult rhabdomyoma.

- Round or lobulated, grossly well circumscribed masses which range from 1 mm to 10 cm in their greatest dimension

- Isolated or multiple

- Solid tan-white homogeneous consistency, often watery and glistening on their cut surface

- Infrequently, calcification and hemorrhage

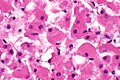

Microscopic Pathology

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, characteristic findings of adult rhabdomyoma include:

- polygonal cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm that are mixed with intracellular vacuolated cells.

- Rhabdomyomas are very well differentiated similarly to striated muscle cells which present markers such as actin, desmin, and myoglobin; dystrophin on their cell membranes.

- Histopathologic findings of fetal rhabdomyoma include spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and muscle fibers.

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, characteristic findings of genital rhabdomyoma include:

- A mixture of fibroblast cells with clusters of mature cells containing distinct cross-striations

- A matrix containing varying amounts of collagen and mucoid material

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, characteristic findings of cardiac rhabdomyoma include cells that closely resemble embryonic cardiac muscle cells.

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, characteristic findings of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the skin include lesions which contain poorly oriented or perpendicular bundles of well-differentiated skeletal muscle with islands of fat, fibrous tissue, and occasionally proliferating nerves.

Causes

- Adult rhabdomyomas are matured neoplasms of clonal origin.

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma may be caused by either sporadic mutation or in the setting of certain genetic disorders.[7]

- The genetic disorder commonly associated with cardiac rhabdomyoma is tuberous sclerosis.[8] Other genetic disorders associated with cardiac rhabdomyomas include basal cell nevus syndrome and Down syndrome in the setting of tuberous sclerosis.[9][10]

- The familial form of tuberous sclerosis are hamartomas that can involve the kidneys, heart, skin, brain, and other organs. The association of cardiac rhabdomyoma and tuberous sclerosis is important and has been explained by strong clinical association. Molecular evidence of this association has been identified as the TSC2 gene missense mutation.

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma is caused by a mutation in the TSC-1 on chromosome 9q34 that encodes for protein hamartin, and TSC-2 on 16p13 that encodes for tuberin. These genes are both tumor suppressor genes that assist in the regulation of growth and differentiation of developing cardiomyocytes.

Differentiating Rhabdomyoma from Other Diseases

- Rhabdomyomas must be differentiated from other diseases, such as:[11]

- Fibroma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Hibernoma

- Reticulohistiocytoma

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Granular cell tumors

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Cardiac rhabdomyomas are usually detected during the first year of life or before birth and accounts for majority of all primary cardiac tumors.

- Worldwide, rhabdomyoma is rare.

- Most of patients with tuberous sclerosis develop a cardiac rhabdomyoma. Similarly, children diagnosed with cardiac rhabdomyomas demonstrate radiologic or clinical findings of tuberous sclerosis or have a positive family history. Rhabdomyoma is extremely rare in the United States. Rhabdomyoma has a relative incidence of 5.8%. The incidence of cardiac rhabdomyoma is 0.002-0.25% at autopsy, 0.02-0.08% in live-born infants, and 0.12% in prenatal reviews.[9][12]

Age

- Adult rhabdomyoma is more commonly observed among patients aged greater than 40 years old.

- Fetal rhabdomyoma is more commonly observed among patients aged between birth and 3 years.

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma is more commonly observed among patients in the pediatric age group.

- Genital rhabdomyoma is more commonly observed among patients in the young and middle-aged women.

- Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas of the skin is more commonly observed among newborns and infants.

Gender

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma affects men and women equally.

- Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin is observed in male and female newborns and infants equally.

- Males are more commonly affected with adult rhabdomyoma than females.

- Males are more commonly affected with fetal rhabdomyoma than females.

- Females are more commonly affected with genital rhabdomyoma than males.

Race

- There is no racial predilection for rhabdomyomas.

Risk Factors

- There are no established risk factors for rhabdomyoma.

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Natural History

- The majority of cases regress spontaneously,however there are reported cases which surgical interventions were necessary,especially if tumor causes cardiac symptoms such as arrhythmia or obstruction. [13][3][14]

- Early clinical features include heart failure, cardiac murmur, and arrhythmia.

- If left untreated, cardiac rhabdomyomas generally follows a complete or partial regression with consequent resolution of symptoms. The majority of rhabdomyomas regress spontaneously, and surgical resection is usually not required unless a child is symptomatic.

- Tumors larger in diameter are more likely to cause arrhythmias or hemodynamic instability, which are associated with an increased risk of death.

- The majority of patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma remain asymptomatic; however, some affected patients become symptomatic in the perinatal period.

Complications

- Common complications of cardiac rhabdomyoma include development of cardiac arrhythmias, ventricular outflow tract obstruction, valvular compromise, and disruption of intracardiac blood flow leading to congestive heart failure and hydrops.

Prognosis

- prognosis is generally good; the survival rate of patients with rhabdomyoma is close to 90%. Rhabdomyomas that alter valve function and lead to [[regurgitation (circulation)|regurgitation} or that obstruct the inflow or ventricular outflow tracts carry a poor prognosis. The long-term prognosis of cardiac rhabdomyoma is affected by the neurologic manifestations associated with tuberous sclerosis.[15]

- The prognosis of patients with rhabdomyomas is chiefly determined by the size, number and location of the lesions as well as the presence or absence of associated anomalies.

- The morbidity of rhabdomyoma depends on the type of lesion and its location.

- Patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas have the highest risk.

- The morbidity of rhabdomyoma depends on the type of lesion and its location.

- Metastases have not been associated with rhabdomyoma.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

- Symptoms of adult rhabdomyoma may include:

- Symptoms of genital rhabdomyoma may include the following:

- Symptoms of cardiac rhabdomyoma may include the following:

- In cardiac rhabdomyoma, symptoms if present, may be caused by obstruction of blood flow through the heart or consist of rhythm disturbances, such as heart block and ventricular tachycardia.[16][17]

Physical Examination

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

- The presence of a round or polypoid mass in the region of the neck in adult rhabdomyoma

- Subcutaneous masses in the head and neck regions in fetal rhabdomyoma

- Vaginal masses in genital rhabdomyoma

- Cardiac rhabdomyomas may present with heart murmurs; if tuberous sclerosis is associated, the patient may display cerebral palsy–type signs. Renal functions may be altered.

Laboratory Findings

- There are no specific laboratory findings associated with rhabdomyoma.

- The following laboratory studies may be ordered to rule out additional conditions:

Imaging Findings

- MRI is the imaging modality of choice for rhabdomyoma. Chest CT scan may be helpful in the diagnosis of cardiac rhabdomyoma.

- On ultrasound, rhabdomyoma is characterized by one or more solid hyper echoic mass(es) located in relation to the myocardium. The small lesions can mimic diffuse myocardial thickening.

- X-Rays of the chest and affected areas of the body may be helpful in the diagnosis of rhabdomyomas.[18]

Other Diagnostic Studies

- Rhabdomyoma may also be diagnosed using biopsy.

- Any masses, including those found in the head and neck of patients with adult rhabdomyoma, should be biopsied to establish a diagnosis.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- Treatment for rhabdomyoma is supportive care.Conservative management includes:[19][20] [21]

- frequent monitoring of patients with echocardiography and electrocardiography.

Adult rhabdomyoma

- In adult patients with laryngeal rhabdomyoma, nasal oxygen may relieve patients breathing difficulties.

- supplemental intravenous fluids may be administered until surgery is performed for those patients having difficulty swallowing.

- patients with adult rhabdomyoma and shortness of breath should restrain from activities which exacerbate their breathing difficulty. Patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma should also restrict their activities.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma

- Pharmacological treatment available for fetal cardiac rhabdomyoma is everolimus.

- Patients with arrhythmias are treated with antiarrhythmic medications.

- Restriction on physical activities in those patients with cardiac clinical symptoms.

- Asymptomatic children with TSC and a rhabdomyoma should have echocardiography every one to three years until regression of cardiac rhabdomyoma is documented.

Genital rhabdomyoma

- In patients with genital rhabdomyoma, urinary tract obstruction may happen, therefore catheterization use may be necessary in order to avoid urinary tract infection *Pregnant patients need to be monitored closely, as they may require a cesarean delivery.[5][22]

Surgery

Adult rhabdomyoma

- Surgical resection of the tumor can only be performed for patients with adult rhabdomyoma if airway obstruction is diagnosed, there have been reports of rare cases of laryngeal rhabdomyoma which may cause breathing difficulty for patients.[23]

Cardiac rhabdomyoma

- Surgical intervention is reserved for patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas who have symptoms of severe hemodynamic compromise or intractable arrhythmias. Surgical management involves removal of the intracavitary portion of the tumor without complete excision of the entire lesion.

Prevention

- There are no primary preventive measures available for rhabdomyoma.

References

- ↑ Beghetti M, Gow RM, Haney I, Mawson J, Williams WG, Freedom RM (1997). "Pediatric primary benign cardiac tumors: a 15-year review". Am Heart J. 134 (6): 1107–14. PMID 9424072.

- ↑ Kocabaş A, Ekici F, Cetin Iİ, Emir S, Demir HA, Arı ME; et al. (2013). "Cardiac rhabdomyomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in 11 children: presentation to outcome". Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 30 (2): 71–9. doi:10.3109/08880018.2012.734896. PMID 23151153.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Becker AE (2000). "Primary heart tumors in the pediatric age group: a review of salient pathologic features relevant for clinicians". Pediatr Cardiol. 21 (4): 317–23. doi:10.1007/s002460010071. PMID 10865004.

- ↑ Elderkin RA, Radford DJ (2002). "Primary cardiac tumours in a paediatric population". J Paediatr Child Health. 38 (2): 173–7. PMID 12031001.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lu DY, Chang S, Cook H, Alizadeh Y, Karam AK, Moatamed NA, Dry SM (April 2012). "Genital rhabdomyoma of the urethra in an infant girl". Hum. Pathol. 43 (4): 597–600. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2011.06.012. PMID 21992817.

- ↑ Bjørndal Sørensen K, Godballe C, Ostergaard B, Krogdahl A (March 2006). "Adult extracardiac rhabdomyoma: light and immunohistochemical studies of two cases in the parapharyngeal space". Head Neck. 28 (3): 275–9. doi:10.1002/hed.20358. PMID 16419079.

- ↑ Burke A, Virmani R (2008). "Pediatric heart tumors". Cardiovasc Pathol. 17 (4): 193–8. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2007.08.008. PMID 18402818.

- ↑ Vaughan CJ, Veugelers M, Basson CT (2001). "Tumors and the heart: molecular genetic advances". Curr Opin Cardiol. 16 (3): 195–200. PMID 11357016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Isaacs H (2004). "Fetal and neonatal cardiac tumors". Pediatr Cardiol. 25 (3): 252–73. doi:10.1007/s00246-003-0590-4. PMID 15360117.

- ↑ Krapp M, Baschat AA, Gembruch U, Gloeckner K, Schwinger E, Reusche E (1999). "Tuberous sclerosis with intracardiac rhabdomyoma in a fetus with trisomy 21: case report and review of literature". Prenat Diagn. 19 (7): 610–3. PMID 10419607.

- ↑ Nasr E, Ibrahim M, Yacoub M (January 2017). "Heart failure in a neonate with multiple cardiac masses". Heart. 103 (1): 18. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310251. PMID 27655257.

- ↑ Delides A, Petrides N, Banis K (2005). "Multifocal adult rhabdomyoma of the head and neck: a case report and literature review". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 262 (6): 504–6. doi:10.1007/s00405-004-0840-y. PMID 15942804.

- ↑ Barnes BT, Procaccini D, Crino J, Blakemore K, Sekar P, Sagaser KG, Jelin AC, Gaur L (May 2018). "Maternal Sirolimus Therapy for Fetal Cardiac Rhabdomyomas". N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (19): 1844–1845. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1800352. PMC 6201692. PMID 29742370.

- ↑ Smythe JF, Dyck JD, Smallhorn JF, Freedom RM (1990). "Natural history of cardiac rhabdomyoma in infancy and childhood". Am J Cardiol. 66 (17): 1247–9. PMID 2239731.

- ↑ Chung C, Lawson JA, Sarkozy V, Riney K, Wargon O, Shand AW, Cooper S, King H, Kennedy SE, Mowat D (November 2017). "Early Detection of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: An Opportunity for Improved Neurodevelopmental Outcome". Pediatr. Neurol. 76: 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.014. PMID 28811058. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Bosi G, Lintermans JP, Pellegrino PA, Svaluto-Moreolo G, Vliers A (1996). "The natural history of cardiac rhabdomyoma with and without tuberous sclerosis". Acta Paediatr. 85 (8): 928–31. PMID 8863873.

- ↑ Jacobs JP, Konstantakos AK, Holland FW, Herskowitz K, Ferrer PL, Perryman RA (1994). "Surgical treatment for cardiac rhabdomyomas in children". Ann Thorac Surg. 58 (5): 1552–5. PMID 7979700.

- ↑ Germ cell tumors. Radiopedia(2015) http://radiopaedia.org/articles/cardiac-rhabdomyoma Accessed on January 25, 2016

- ↑ Tiberio D, Franz DN, Phillips JR (2011). "Regression of a cardiac rhabdomyoma in a patient receiving everolimus". Pediatrics. 127 (5): e1335–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2910. PMID 21464184.

- ↑ Wagner R, Riede FT, Seki H, Hornemann F, Syrbe S, Daehnert I; et al. (2015). "Oral Everolimus for Treatment of a Giant Left Ventricular Rhabdomyoma in a Neonate-Rapid Tumor Regression Documented by Real Time 3D Echocardiography". Echocardiography. 32 (12): 1876–9. doi:10.1111/echo.13015. PMID 26199144.

- ↑ Öztunç F, Atik SU, Güneş AO (October 2015). "Everolimus treatment of a newborn with rhabdomyoma causing severe arrhythmia". Cardiol Young. 25 (7): 1411–4. doi:10.1017/S1047951114002261. PMID 26339757.

- ↑ Dodat H, Paulhac JB, Macabeo V, Bouvier R (1987). "[Benign tumors of the posterior urethra in children. Apropos of an unusual case of rhabdomyoma of fetal type]". J Urol (Paris) (in French). 93 (1): 43–6. PMID 3031168.

- ↑ Pinho MM, de Carvalho E Castro J, Ramos RG (October 2013). "Adult rhabdomyoma of the larynx". Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 17 (4): 415–8. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351671. PMC 4399195. PMID 25992049. Vancouver style error: missing comma (help)