Gestational trophoblastic disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Incidence and Mortality== | ==Incidence and Mortality== | ||

The reported incidence of GTD varies widely worldwide, from a low of 23 per 100,000 pregnancies (Paraguay) to a high of 1,299 per 100,000 pregnancies (Indonesia). | The reported incidence of GTD varies widely worldwide, from a low of 23 per 100,000 pregnancies (Paraguay) to a high of 1,299 per 100,000 pregnancies (Indonesia). However, at least part of this variability is caused by differences in diagnostic criteria and reporting. The reported incidence in the United States is about 110 to 120 per 100,000 pregnancies. The reported incidence of choriocarcinoma, the most aggressive form of GTD, in the United States is about 2 to 7 per 100,000 pregnancies. The U.S. age-standardized (1960 World Population Standard) incidence rate of choriocarcinoma is about 0.18 per 100,000 women between the ages of 15 years and 49 years. | ||

==Risk Factors== | ==Risk Factors== | ||

Two factors have consistently been associated with an increased risk of GTD: | Two factors have consistently been associated with an increased risk of GTD: | ||

Maternal age. | Maternal age. | ||

History of hydatidiform mole (HM). | History of hydatidiform mole (HM). | ||

If a woman has been previously diagnosed with an HM, she carries a 1% risk of HM in subsequent pregnancies. This increases to approximately 25% with more than one prior HM. The risk associated with maternal age is bimodal, with increased risk both for mothers younger than 20 years and older than 35 years (and particularly for mothers >45 years). Relative risks are in the range of 1.1 to 11 for both the younger and older age ranges compared with ages 20 to 35 years. However, a population-based HM registry study suggests that the age-related patterns of the two major types of HM—complete and partial HM—are distinct.[3] (Refer to the Cellular Classification of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease section of this summary for more information.) In that study, the rate of complete HM was highest in women younger than 20 years and then decreased monotonically with age. However, the rates of partial HM increased for the entire age spectrum, suggesting possible differences in etiology. The association with paternal age is inconsistent. | If a woman has been previously diagnosed with an HM, she carries a 1% risk of HM in subsequent pregnancies. This increases to approximately 25% with more than one prior HM. The risk associated with maternal age is bimodal, with increased risk both for mothers younger than 20 years and older than 35 years (and particularly for mothers >45 years). Relative risks are in the range of 1.1 to 11 for both the younger and older age ranges compared with ages 20 to 35 years. However, a population-based HM registry study suggests that the age-related patterns of the two major types of HM—complete and partial HM—are distinct.[3] (Refer to the Cellular Classification of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease section of this summary for more information.) In that study, the rate of complete HM was highest in women younger than 20 years and then decreased monotonically with age. However, the rates of partial HM increased for the entire age spectrum, suggesting possible differences in etiology. The association with paternal age is inconsistent. A variety of exposures have been examined, with no clear associations found with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, and oral contraceptive use. | ||

==Clinical Features== | ==Clinical Features== | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

The prognosis for cure of patients with GTDs is good even when the disease has spread to distant organs, especially when only the lungs are involved. Therefore, the traditional TNM staging system has limited prognostic value.[4] The probability of cure depends on the following: | The prognosis for cure of patients with GTDs is good even when the disease has spread to distant organs, especially when only the lungs are involved. Therefore, the traditional TNM staging system has limited prognostic value.[4] The probability of cure depends on the following: | ||

*Histologic type (invasive mole or choriocarcinoma). | |||

*Extent of spread of the disease/largest tumor size. | |||

*Level of serum beta-hCG. | |||

*Duration of disease from the initial pregnancy event to start of treatment. | |||

*Number and specific sites of metastases. | |||

*Nature of antecedent pregnancy. | |||

*Extent of prior treatment. | |||

Selection of treatment depends on these factors plus the patient’s desire for future pregnancies. The beta-hCG is a sensitive marker to indicate the presence or absence of disease before, during, and after treatment. Given the extremely good therapeutic outcomes of most of these tumors, an important goal is to distinguish patients who need less-intensive therapies from those who require more-intensive regimens to achieve a cure. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 19:12, 6 October 2015

For patient information on Hydatiform mole, click here

For patient information on Choriocarcinoma, click here

| Gestational trophoblastic disease | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

|---|---|

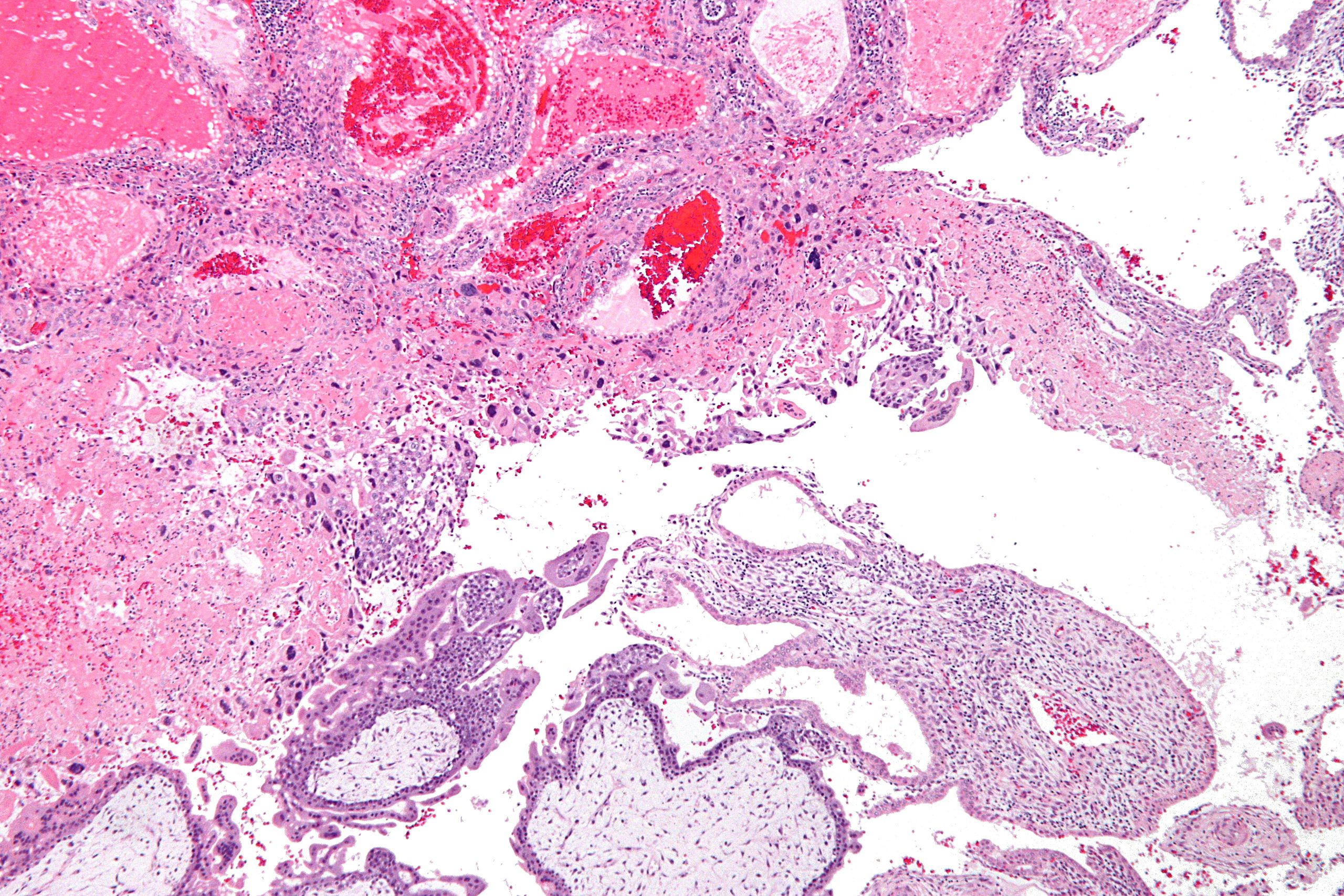

| Micrograph of intermediate trophoblast, decidua and a hydatidiform mole (bottom of image). H&E stain. |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a term used for a group of pregnancy-related tumours. These tumours are rare, and they appear when cells in the womb start to proliferate uncontrollably. The cells that form gestational trophoblastic tumours are called trophoblasts and come from tissue that grows to form the placenta during pregnancy.

There are several different types of GTD. Hydatidiform moles are, in most cases, benign, but may, sometimes, develop into invasive moles, or, in rare cases, into choriocarcinoma, which is likely to spread quickly,[1][2] but which is very sensitive to chemotherapy, and has a very good prognosis. Gestational trophoblasts are of particular interest to cell biologists because, like cancer, these cells invade tissue (the uterus), but unlike cancer, they sometimes "know" when to stop.[citation needed]

GTD can simulate pregnancy, because the uterus may contain fetal tissue, albeit abnormal. This tissue may grow at the same rate as a normal pregnancy, and produces chorionic gonadotropin, a hormone which is measured to monitor fetal well-being.[3]

While GTD overwhelmingly affects women of child-bearing age, it may rarely occur in postmenopausal women.[4]

Incidence and Mortality

The reported incidence of GTD varies widely worldwide, from a low of 23 per 100,000 pregnancies (Paraguay) to a high of 1,299 per 100,000 pregnancies (Indonesia). However, at least part of this variability is caused by differences in diagnostic criteria and reporting. The reported incidence in the United States is about 110 to 120 per 100,000 pregnancies. The reported incidence of choriocarcinoma, the most aggressive form of GTD, in the United States is about 2 to 7 per 100,000 pregnancies. The U.S. age-standardized (1960 World Population Standard) incidence rate of choriocarcinoma is about 0.18 per 100,000 women between the ages of 15 years and 49 years.

Risk Factors

Two factors have consistently been associated with an increased risk of GTD:

Maternal age. History of hydatidiform mole (HM).

If a woman has been previously diagnosed with an HM, she carries a 1% risk of HM in subsequent pregnancies. This increases to approximately 25% with more than one prior HM. The risk associated with maternal age is bimodal, with increased risk both for mothers younger than 20 years and older than 35 years (and particularly for mothers >45 years). Relative risks are in the range of 1.1 to 11 for both the younger and older age ranges compared with ages 20 to 35 years. However, a population-based HM registry study suggests that the age-related patterns of the two major types of HM—complete and partial HM—are distinct.[3] (Refer to the Cellular Classification of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease section of this summary for more information.) In that study, the rate of complete HM was highest in women younger than 20 years and then decreased monotonically with age. However, the rates of partial HM increased for the entire age spectrum, suggesting possible differences in etiology. The association with paternal age is inconsistent. A variety of exposures have been examined, with no clear associations found with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, and oral contraceptive use.

Clinical Features

GTDs contain paternal chromosomes and are placental, rather than maternal, in origin. The most common presenting symptoms are vaginal bleeding and a rapidly enlarging uterus, and GTD should be considered whenever a premenopausal woman presents with these findings. Because the vast majority of GTD types are associated with elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels, an hCG blood level and pelvic ultrasound are the initial steps in the diagnostic evaluation. In addition to vaginal bleeding and uterine enlargement, other presenting symptoms or signs may include the following:

Pelvic pain or sensation of pressure. Anemia. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Hyperthyroidism (secondary to the homology between the beta-subunits of hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which causes hCG to have weak TSH-like activity). Preeclampsia early in pregnancy.

The most common antecedent pregnancy in GTD is that of an HM.

Choriocarcinoma most commonly follows a molar pregnancy but can follow a normal pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or abortion, and it should always be considered when a patient has continued vaginal bleeding in the postdelivery period. Other possible signs include neurologic symptoms (resulting from brain metastases) in a female within the reproductive age group and asymptomatic lesions on routine chest x-ray.

Prognostic Factors and Survivorship

The prognosis for cure of patients with GTDs is good even when the disease has spread to distant organs, especially when only the lungs are involved. Therefore, the traditional TNM staging system has limited prognostic value.[4] The probability of cure depends on the following:

- Histologic type (invasive mole or choriocarcinoma).

- Extent of spread of the disease/largest tumor size.

- Level of serum beta-hCG.

- Duration of disease from the initial pregnancy event to start of treatment.

- Number and specific sites of metastases.

- Nature of antecedent pregnancy.

- Extent of prior treatment.

Selection of treatment depends on these factors plus the patient’s desire for future pregnancies. The beta-hCG is a sensitive marker to indicate the presence or absence of disease before, during, and after treatment. Given the extremely good therapeutic outcomes of most of these tumors, an important goal is to distinguish patients who need less-intensive therapies from those who require more-intensive regimens to achieve a cure.

References

- ↑ Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS (August 2010). "Gestational trophoblastic disease". Lancet. 376 (9742): 717–29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2. PMID 20673583.

- ↑ Lurain JR (December 2010). "Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 203 (6): 531–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.073. PMID 20728069.

- ↑ Gestational trophoblastic disease: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Chiang JW, Berek JS. In: UpToDate [Textbook of Medicine]. Basow, DS (Ed). Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, and Wolters Kluwer Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2010.

- ↑ Chittenden B, Ahamed E, Maheshwari A (August 2009). "Choriocarcinoma in a postmenopausal woman". Obstet Gynecol. 114 (2 Pt 2): 462–5. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aa97e7. PMID 19622962.