Sandbox:Cherry

Pathophysiology prev

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5szNmKtyBW4%7C350}} |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Sandbox:Cherry On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sandbox:Cherry |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Liver transplantation

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO, also known as pyloric obstruction) is not a single entity; it is the clinical and pathophysiological consequence of any disease process that produces a mechanical impediment to gastric emptying. Clinical entities that can result in GOO generally are categorized into two well-defined groups of causes: benign and malignant. This classification facilitates discussion of management and treatment. In the past, when peptic ulcer disease (PUD) was more prevalent, benign causes were the most common; however, one review showed that only 37% of patients with GOO have benign disease and the remaining patients have obstruction secondary to malignancy.[1] Gastric outlet obstruction can be a diagnostic and treatment dilemma. Despite medical advances in the acid suppression mechanism, the incidence of GOO remains a prevalent clinical problem in benign PUD. Also, an increase in the number of cases of GOO seems to be noted secondary to malignancy; this is possibly due to improvements in cancer therapy, which allow patients to live long enough to develop this complication. As part of the initial workup, exclude the possibility of functional nonmechanical causes of obstruction, such as diabetic gastroparesis. Once a mechanical obstruction is confirmed, differentiate between benign and malignant processes because definitive treatment is based on recognition of the specific underlying cause. Carry out diagnosis and treatment expeditiously, because delay may result in further compromise of the patient's nutritional status. Delay will also further compromise edematous tissue and complicate surgical intervention. Orient initial management to identification of the primary underlying cause and to the correction of volume and electrolyte abnormalities. Barium swallow studies and upper endoscopy are the main tests used to help make the diagnosis. Tailor treatment to the specific cause.

Anatomy The stomach is located mainly in the left upper quadrant beneath the diaphragm and is attached superiorly to the esophagus and distally to the duodenum. The stomach is divided into four portions: cardia, body, antrum, and pylorus. Inflammation, scarring, or infiltration of the antrum and pylorus are associated with the development of GOO. The duodenum begins immediately beyond the pylorus and mostly is a retroperitoneal structure, wrapping around the head of the pancreas. The duodenum classically is divided into four portions. It is intimately related to the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas; therefore, a malignant process of any adjacent structure may cause outlet obstruction due to extrinsic compression. Pathophysiology Intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction of the pyloric channel or duodenum is the usual pathophysiology of GOO; the mechanism of obstruction depends upon the underlying etiology. Patients present with intermittent symptoms that progress until obstruction is complete. Vomiting is the cardinal symptom. Initially, patients may demonstrate better tolerance to liquids than solid food. In a later stage, patients may develop significant weight loss due to poor caloric intake. Malnutrition is a late sign, but it may be very profound in patients with concomitant malignancy. In the acute or chronic phase of obstruction, continuous vomiting may lead to dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. When obstruction persists, patients may develop significant and progressive gastric dilatation. The stomach eventually loses its contractility. Undigested food accumulates and may represent a constant risk for aspiration pneumonia. Etiology The major benign causes of GOO are PUD, gastric polyps, ingestion of caustics, pyloric stenosis, congenital duodenal webs, gallstone obstruction (Bouveret syndrome), pancreatic pseudocysts, and bezoars. PUD manifests in approximately 5% of all patients with GOO. Ulcers within the pyloric channel and first portion of the duodenum usually are responsible for outlet obstruction. Obstruction can occur in an acute setting secondary to acute inflammation and edema or, more commonly, in a chronic setting secondary to scarring and fibrosis. Helicobacter pylori has been implicated as a frequent associated finding in patients with GOO, but its exact incidence has not been defined precisely. Within the pediatric population, pyloric stenosis constitutes the most important cause of GOO. Pyloric stenosis occurs in 1 per 750 births. It is more common in boys than in girls and also is more common in first-born children. Pyloric stenosis is the result of gradual hypertrophy of the circular smooth muscle of the pylorus. (See image below.)

Anatomic changes associated with pyloric stenosis.

View Media Gallery Pancreatic cancer is the most common malignancy causing GOO. Outlet obstruction may occur in 10-20% of patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Other tumors that may obstruct the gastric outlet include ampullary cancer, duodenal cancer, cholangiocarcinomas, and gastric cancer. Metastases to the gastric outlet also may be caused by other primary tumors. Physical Examination Physical examination often demonstrates the presence of chronic dehydration and malnutrition. A dilated stomach may be appreciated as a tympanitic mass in the epigastric area and/or left upper quadrant.

Dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities can be demonstrated by routine laboratory examinations. Increases in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine are late features of dehydration.

Prolonged vomiting causes loss of hydrochloric acid and produces an increase of bicarbonate in the plasma to compensate for the lost chloride and sodium. The result is a hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Alkalosis shifts the intracellular potassium to the extracellular compartment, and the serum positive potassium is increased factitiously. With continued vomiting, the renal excretion of potassium increases in order to preserve sodium. The adrenocortical response to hypovolemia intensifies the exchange of potassium for sodium at the distal tubule, with subsequent aggravation of the hypokalemia Physical Examination Physical examination often demonstrates the presence of chronic dehydration and malnutrition. A dilated stomach may be appreciated as a tympanitic mass in the epigastric area and/or left upper quadrant. Dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities can be demonstrated by routine laboratory examinations. Increases in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine are late features of dehydration. Prolonged vomiting causes loss of hydrochloric acid and produces an increase of bicarbonate in the plasma to compensate for the lost chloride and sodium. The result is a hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Alkalosis shifts the intracellular potassium to the extracellular compartment, and the serum positive potassium is increased factitiously. With continued vomiting, the renal excretion of potassium increases in order to preserve sodium. The adrenocortical response to hypovolemia intensifies the exchange of potassium for sodium at the distal tubule, with subsequent aggravation of the hypokalemia Once the diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is suspected, request a surgical consultation. GOO due to benign ulcer disease may be treated medically if results of imaging studies or endoscopy determine that acute inflammation and edema are the principal causes of the outlet obstruction (as opposed to scarring and fibrosis, which may be fixed).

If medical therapy conducted for a reasonable period fails to alleviate the obstruction, then surgical intervention becomes appropriate. Typically, if resolution or improvement is not seen within 48-72 hours, surgical intervention is necessary. The choice of surgical procedure depends upon the patient's particular circumstances; however, vagotomy and antrectomy should be considered the criterion standard against which the efficacy of other procedures is measured.

Laboratory Studies Obtain a complete blood count (CBC). Check the hemoglobin and hematocrit to rule out the possibility of anemia. Obtain an electrolyte panel. As noted previously, identifying and correcting electrolyte abnormalities that tend to occur is essential. Liver function tests may be helpful, particularly when a malignant etiology is suspected. A test for H pylori is helpful when the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is suspected.

Imaging Studies Plain abdominal radiography, contrast upper gastrointestinal (GI) studies (Gastrografin or barium), and computed tomography (CT) with oral contrast are helpful. (See the images below.) Plain radiographs, including the obstruction series (ie, supine abdomen, upright abdomen, chest posteroanterior), can demonstrate the presence of gastric dilatation and may be helpful in distinguishing the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Procedures Upper endoscopy (see the image below) can help visualize the gastric outlet and may provide a tissue diagnosis when the obstruction is intraluminal. The sodium chloride load test is a traditional clinical nonimaging study that may be helpful. The traditional sodium chloride load test is performed by infusing 750 mL of sodium chloride solution into the stomach via a nasogastric tube (NGT). A diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is made if more than 400 mL remains in the stomach after 30 minutes. Nuclear gastric emptying studies measure the passage of orally administered radionuclide over time. Unfortunately, both the nuclear test and the saline load test may produce abnormal results in functional states. Barium upper GI studies are very helpful because they can delineate the gastric silhouette and demonstrate the site of obstruction. An enlarged stomach with a narrowing of the pyloric channel or first portion of the duodenum helps differentiate GOO from gastroparesis. The specific cause may be identified as an ulcer mass or intrinsic tumor. In the presence of PUD, perform endoscopic biopsy to rule out the presence of malignancy. In the case of peripancreatic malignancy, CT-guided biopsy may be helpful in establishing a preoperative diagnosis. Needle-guided biopsy also may be helpful in establishing the presence of metastatic disease. This knowledge may impact the magnitude of the procedure planned to alleviate the GOO. Histologic findings relate to the individual underlying cause.

Video codes

Normal video

{{#ev:youtube|x6e9Pk6inYI}} {{#ev:youtube|4uSSvD1BAHg}} {{#ev:youtube|PQXb5D-5UZw}}

Video in table

Floating video

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypYI_lmLD7g%7C350}} |

Redirect

- REDIRECTEsophageal web

synonym website

https://mq.b2i.sg/snow-owl/#!terminology/snomed/10743008

Image

Image to the right

|

Image and text to the right

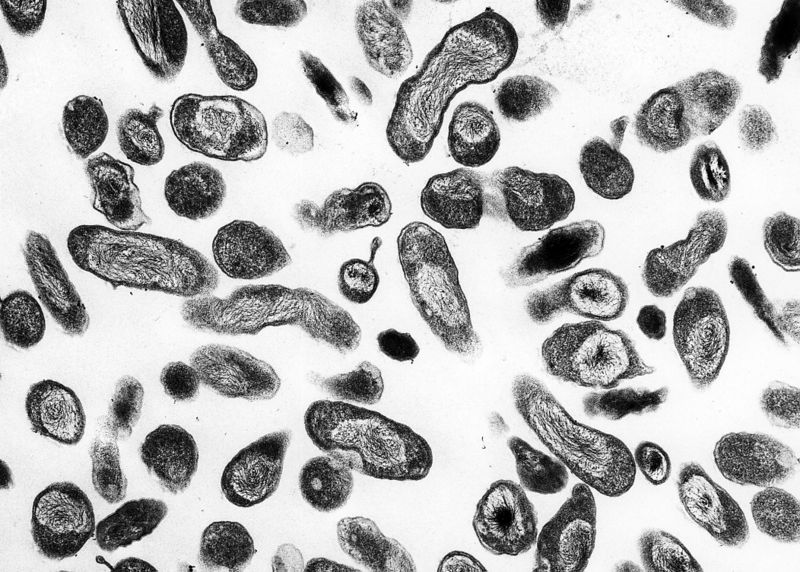

<figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline> </figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

</figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

Gallery

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Libre Pathology. http://librepathology.org/wiki/index.php/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas

REFERENCES

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/2/2f/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_2.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/a/a3/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histopathology_3.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[1]](/images/d/d5/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_4.JPG)