Actinomycosis pathophysiology

|

Actinomycosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Actinomycosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Actinomycosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Actinomycosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Actinomycosis is a chronic pyogenic bacterial infection caused by Actinomyces species. Infection most frequently follows dental work, trauma, surgery, or other medical conditions. When there is break in the mucosa, anywhere from the mouth to the rectum they reach tissues and cause damage. Incubation period of Actinomycosis varies from one to four weeks. But occasionally, it may be as long as several months. Actinomycosis elicits both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses

Pathophysiology

- Actinomycosis is caused by the bacteria Actinomyces. The pathophysiology of Actinomycosis can be described in the following steps. [1][2][3][4][5][6]

Transmission

- Actinomyces are part of natural flora of human body, resides in the oral cavity, lower gastrointestinal tract and urogenital tract.

- They are nonvirulent under normal conditions

- When there is a breach in normal mucosal architecture, anywhere from the mouth to the rectum they enter tissues and cause damage.

| Types | Site of Infection | Source of infection |

|---|---|---|

| Cervicofacial actinomycosis |

|

|

| Thoracic

actinomycosis |

|

|

| Abdominal actinomycosis | Abdomen |

|

| Pelvic

actinomycosis |

Pelvis |

|

| Central nervous system

actinomycosis |

CNS |

|

Incubation

Incubation period of actinomycosis varies from one to four weeks. But occasionally, it may be as long as several months.

Dissemination

Following transmission, lesions spread by direct extension.

Seeding

- Once the endogenous bacteria are introduced into the tissues, they multiply due to low oxygen tension.

- It triggers an inflammatory reaction which results in the formation of hard yellow hard granules(sulfur granules).

- These granules represent solidified bacterial filaments with surrounding tissue exudates.

- Inflammatory mediators along with various bacterial toxins and proteolytic enzymes from the neutrophils are released leading to abscess formation.

- A fibrous wall develops around the abscess along with sulfur granules.

- Extension of the abscess to skin leads to the formation of sinus tracts and pus drains out through these sinuses.

Immune response

Actinomycosis elicits both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses

Genetics

There is no known genetic association to actinomycosis

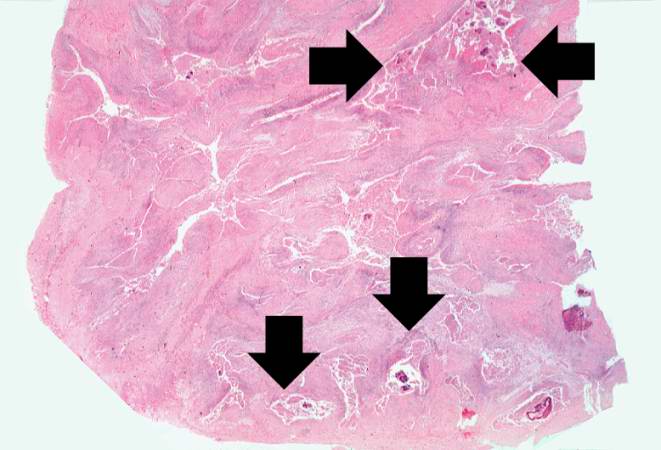

Gross Pathology

On gross pathology the following features can be noticed:

- Single or multiple abscesses

- Indurated masses with hard fibrous walls and soft central loculations containing white or yellow pus.

- Granules are seen grossly.

- Sinus tracts extended from abscesses to the skin surface or into organs; vertebral bone, and retroperitoneal tissue.

- Pleural, pericardial, or serosal thickening if the infection involves lung, heart, and wall of the bowel.

Microscopic pathology

Microscopic findings include

- Liquefaction type of necrosis in the center of abscess with a surrounding outer layer of granulation tissue along with lymphocytes and neutrophils.

- Gram positive organism with branching filaments forming segment-like structures form colonies.

\

{{#ev:youtube|pvasI_yy3R4}}

References

- ↑ Volante M, Contucci AM, Fantoni M, Ricci R, Galli J (2005). "Cervicofacial actinomycosis: still a difficult differential diagnosis". Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 25 (2): 116–9. PMC 2639881. PMID 16116835.

- ↑ Sharkawy AA (2007). "Cervicofacial actinomycosis and mandibular osteomyelitis". Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 21 (2): 543–56, viii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.007. PMID 17561082.

- ↑ Peipert, Jeffrey F. (2004). "Actinomyces: Normal Flora or Pathogen?". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 104 (Supplement): 1132–1133. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000145267.59208.e7. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ↑ Higashi Y, Nakamura S, Ashizawa N, Oshima K, Tanaka A, Miyazaki T, Izumikawa K, Yanagihara K, Yamamoto Y, Miyazaki Y, Mukae H, Kohno S (2017). "Pulmonary Actinomycosis Mimicking Pulmonary Aspergilloma and a Brief Review of the Literature". Intern. Med. 56 (4): 449–453. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7620. PMID 28202870.

- ↑ Schaal KP, Lee HJ (1992). "Actinomycete infections in humans--a review". Gene. 115 (1–2): 201–11. PMID 1612438.

- ↑ Brown, James R. (1973). "Human actinomycosisA study of 181 subjects". Human Pathology. 4 (3): 319–330. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(73)80097-8. ISSN 0046-8177.

- ↑ Smego RA (1987). "Actinomycosis of the central nervous system". Rev Infect Dis. 9 (5): 855–65. PMID 3317731.