Secondary amyloidosis pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{Secondary amyloidosis}} | {{Secondary amyloidosis}} | ||

{{CMG}}; {{AE}} | {{CMG}}; {{AE}} {{Sahar}} | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

Revision as of 04:19, 3 November 2019

|

Secondary amyloidosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Secondary amyloidosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Secondary amyloidosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Secondary amyloidosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Sahar Memar Montazerin, M.D.[2]

Overview

AA amyloid is an abnormal insoluble extracellular protein derived from the spontaneous aggregation of fibrils composed of misfolded proteins, called amyloid precursors. In secondary amyloidosis, the amyloid precursor is SAA, an acute phase reactant, encoded by SAA 1&2 genes. In secondary amyloidosis, intermediate products of SAA metabolism tend to aggregate and form protofilaments that accumulate within extracellular space and form the insoluble amyloid deposits. Secondary amyloidosis is associated with chronic inflammation (such as tuberculosis or rheumatoid arthritis).

Pathophysiology

- AA amyloid is an abnormal insoluble extracellular protein derived from the spontaneous aggregation of fibrils composed of misfolded proteins, called amyloid precursors.[1][2]

- In secondary amyloidosis, the amyloid precursor is SAA, an acute phase reactant, encoded by SAA 1&2 genes.

- Normally, SAA increased during the inflammatory process and then taken up by macrophages and degraded within lysosomal compartments.

- In patients with secondary amyloidosis, intermediate products of SAA metabolism tend to aggregate and form protofilaments.

- These protofilaments with other protein materials accumulate within extracellular space and form the insoluble amyloid deposits.

- Amyloid deposition can disrupt tissue structure of involved organ and consequently leads to organ failure.[3]

Associated Conditions

- Conditions associated with AA amyloidosis include:[4][5][6]

- Monogenic periodic fever syndromes, such as:

- Tuberculosis

- Leprosy

- Whipple Disease

- Osteomyelitis

- Chronic pyelonephritis

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis

- Chronic cutaneous ulcers

- Conditions Predisposing to chronic infections including:

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchiectasis

- Kartagener syndrome

- Epidermolysis bullosa

- Injected drug abuse

- Jejuno-ileal bypass

- Paraplegia

- Sickle cell anemia

- Immunodeficiency

- Common variable immunodeficiency

- Cyclic neutropenia

- Hyperimmunoglobulin M syndrome

- Hypogammaglobulinemia

- Sex-linked agammaglobulinemia

- Human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS

- Neoplasia

- Adenocarcinoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Carcinoid tumor

- Castleman disease

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- Hairy cell leukemia

- Hepatic adenoma

- Hodgkin disease

- Mesothelioma

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Sarcoma

- Inflammatory Arthritis

- Adult-onset Still disease

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Psoriatic arthropathy

- Reiter syndrome

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Gout

- Systemic Vasculitis

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis

- Behcet disease

- Giant cell arteritis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Takayasu arteritis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn disease

- Others include:

- Atrial myxoma

- Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurism

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

- SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome

- Sarcoidosis

- Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy

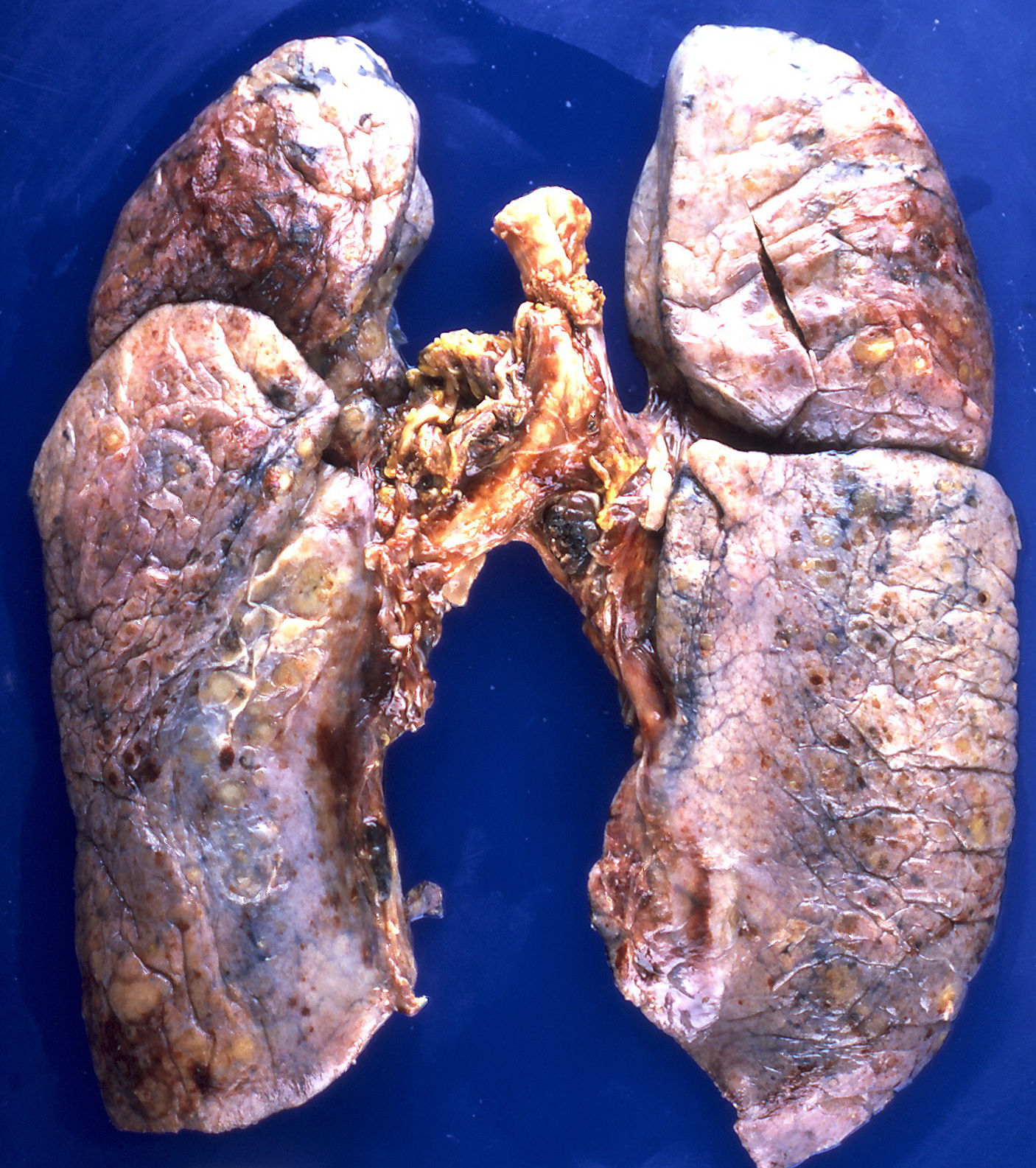

Gross Pathology

On gross pathology, the organs affected by amyloidosis can be characterized by the following features:

- Porcelain like or waxy appearance

- Enlargement

Images

Microscopic Pathology

On microscopic histopathological analysis, amyloidosis is characterized by:[10][11]

- Green birefringence under polarized light after Congo red staining (appears red under normal light)

- Linear non-branching fibrils (indefinite length with an approximately same diameter)

- Distinct X-ray diffraction pattern consistent with Pauling's model of a cross-beta fibril

Images

References

- ↑ Jayaraman, Shobini; Gantz, Donald L.; Haupt, Christian; Gursky, Olga (2017). "Serum amyloid A forms stable oligomers that disrupt vesicles at lysosomal pH and contribute to the pathogenesis of reactive amyloidosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (32): E6507–E6515. doi:10.1073/pnas.1707120114. ISSN 0027-8424.

- ↑ Kisilevsky, Robert; Raimondi, Sara; Bellotti, Vittorio (2016). "Historical and Current Concepts of Fibrillogenesis and In vivo Amyloidogenesis: Implications of Amyloid Tissue Targeting". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 3. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2016.00017. ISSN 2296-889X.

- ↑ Wechalekar AD, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN (June 2016). "Systemic amyloidosis". Lancet. 387 (10038): 2641–2654. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01274-X. PMID 26719234.

- ↑ Blank, Norbert; Hegenbart, Ute; Dietrich, Sascha; Brune, Maik; Beimler, Jörg; Röcken, Christoph; Müller-Tidow, Carsten; Lorenz, Hanns-Martin; Schönland, Stefan O. (2018). "Obesity is a significant susceptibility factor for idiopathic AA amyloidosis". Amyloid. 25 (1): 37–45. doi:10.1080/13506129.2018.1429391. ISSN 1350-6129.

- ↑ van der Hilst, J. C. H.; Yamada, T.; Op den Camp, H. J. M.; van der Meer, J. W. M.; Drenth, J. P. H.; Simon, A. (2008). "Increased susceptibility of serum amyloid A 1.1 to degradation by MMP-1: potential explanation for higher risk of type AA amyloidosis". Rheumatology. 47 (11): 1651–1654. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken371. ISSN 1462-0324.

- ↑ Papa, Riccardo; Doglio, Matteo; Lachmann, Helen J.; Ozen, Seza; Frenkel, Joost; Simon, Anna; Neven, Bénédicte; Kuemmerle-Deschner, Jasmin; Ozgodan, Huri; Caorsi, Roberta; Federici, Silvia; Finetti, Martina; Trachana, Maria; Brunner, Jurgen; Bezrodnik, Liliana; Pinedo Gago, Mari Carmen; Maggio, Maria Cristina; Tsitsami, Elena; Al Suwairi, Wafaa; Espada, Graciela; Shcherbina, Anna; Aksu, Guzide; Ruperto, Nicolino; Martini, Alberto; Ceccherini, Isabella; Gattorno, Marco (2017). "A web-based collection of genotype-phenotype associations in hereditary recurrent fevers from the Eurofever registry". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 12 (1). doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0720-3. ISSN 1750-1172.

- ↑ By Yale Rosen from USA - Amyloidosis, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31127928

- ↑ By Ed Uthman, MD - https://www.flickr.com/photos/euthman/377537238/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1629764

- ↑ By Ed Uthman, MD - https://www.flickr.com/photos/euthman/377538012/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1629740

- ↑

- ↑ Röcken C, Shakespeare A (February 2002). "Pathology, diagnosis and pathogenesis of AA amyloidosis". Virchows Arch. 440 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s00428-001-0582-9. PMID 11964039.

- ↑ By Michael Feldman, MD, PhDUniversity of Pennsylvania School of Medicine - http://www.healcentral.org/healapp/showMetadata?metadataId=38717, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=870218

- ↑ By Ed Uthman, MD - https://www.flickr.com/photos/euthman/377559787/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1629716

- ↑ By Ed Uthman, MD - https://www.flickr.com/photos/euthman/377559955/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1629705