Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Related Key Words and Synonyms: vCJD

Epidemiology and Demographics

U.S. Surveillance for variant CJD

The possibility that BSE can spread to humans has focused increased attention on the desirability of enhancing national surveillance for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in the United States in order to detect variant CJD. Improving methods to detect classic CJD, such as increasing the number of autopsies on patients with suspected prion disease, enhances the ability to identify cases of variant CJD.

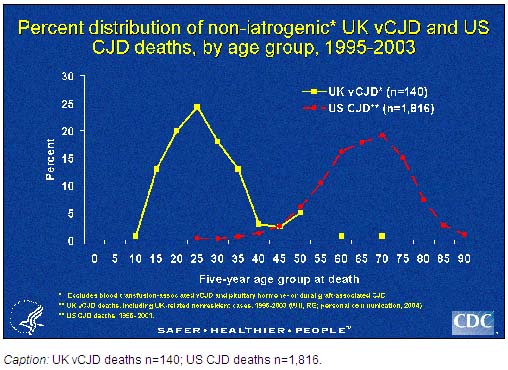

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) monitors the trends and current incidence of classic CJD in the United States through several surveillance mechanisms. The oldest and most systematic method includes analyzing death certificate information from U.S. multiple cause-of-death data, compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. During 1979-2003 the average annual age adjusted death rates of classic CJD have remained relatively stable. Moreover, deaths from non-iatrogenic CJD in persons aged <30 years in the United States remain extremely rare (<5 cases per 1 billion per year). In contrast, in the United Kingdom, over half of the patients who died with vCJD were in this young age group.

In addition, CDC collects, reviews and when indicated, actively investigates reports by health care personnel or institutions of possible iatrogenic CJD and variant CJD cases. Finally and very importantly,, in 1996-97, CDC established, in collaboration with the American Association of Neuropathologists, the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center at Case Western Reserve University, which performs special diagnostic tests for prion diseases, including post-mortem tests that can detect vCJD.

vCJD Cases Reported in the US

Three cases of vCJD have been reported from the United States. By convention, variant CJD cases are ascribed to the country of initial symptom onset, regardless of where the exposure occurred. There is strong evidence that suggests that two of the three cases were exposed to the BSE agent in the United Kingdom and that the third was exposed while living in Saudi Arabia.

The first patient was born in the United Kingdom in the late 1970's and lived there until a move to Florida in 1992. The patient had onset of symptoms in November 2001 and died in June of 2004. The patient never donated or received blood, plasma, or organs, never received human growth hormone, nor did the patient ever have major surgery other than having wisdom teeth extracted in 2001. Additionally, there was no family history of CJD.

The second patient resided in Texas during 2001-2005. Symptoms began in early 2005 while the patient was in Texas. He then returned to the United Kingdom, where his illness progressed, and a diagnosis of variant CJD was made. The diagnosis was confirmed neuropathologically at the time of the patient's death. While living in the United States, the patient had no history of hospitalization, of having invasive medical procedures, or of donation or receipt of blood and blood products. The patient almost certainly acquired the disease in the United Kingdom. He was born in the United Kingdom and lived there throughout the defined period of risk (1980-1996) for human exposure to the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, commonly known as "mad cow" disease). His stay in the United States was too brief relative to what is known about the incubation period for variant CJD.

The third patient was born and raised in Saudi Arabia and has lived in the United States since late 2005. The patient occasionally stayed in the United States for up to 3 months at a time since 2001 and there was a shorter visit in 1989. The patient's onset of symptoms occurred in Spring 2006. In late November 2006, the Clinical Prion Research Team at the University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center confirmed the vCJD clinical diagnosis by pathologic study of adenoid and brain biopsy tissues. The patient has no history of receipt of blood, a past neurosurgical procedure, or residing in or visiting countries of Europe. Based on the patient's history, the occurrence of a previously reported Saudi case of vCJD attributed to likely consumption of BSE-contaminated cattle products in Saudi Arabia, and the expected greater than 7 year incubation period for food-related vCJD, this U.S. case-patient was most likely infected from contaminated cattle products consumed as a child when living in Saudi Arabia (1). The patient has no history of donating blood and the public health investigation has identified no known risk of transmission to U.S. residents from this patient.

Have any cases of variant CJD (vCJD) been reported in the United States?

Yes, three cases of vCJD have been reported from the United States. By convention, variant CJD cases are ascribed to the country of initial symptom onset, regardless of where the exposure occurred. There is strong evidence that suggests that two of the three cases were exposed to the BSE agent in the United Kingdom and that the third was exposed while living in Saudi Arabia.

The first patient was born in the United Kingdom in the late 1970's and lived there until a move to Florida in 1992. The patient had onset of symptoms in November 2001 and died in June of 2004. The patient never donated or received blood, plasma, or organs, never received human growth hormone, nor did the patient ever have major surgery other than having wisdom teeth extracted in 2001. Additionally, there was no family history of CJD.

The second patient resided in Texas during 2001-2005. Symptoms began in early 2005 while the patient was in Texas. He then returned to the United Kingdom, where his illness progressed, and a diagnosis of variant CJD was made. The diagnosis was confirmed neuropathologically in early 2006 at the time of the patient's death. While living in the United States, the patient had no history of hospitalization, of having invasive medical procedures, or of donation or receipt of blood and blood products. The patient almost certainly acquired the disease in the United Kingdom. He was born in the United Kingdom and lived there throughout the defined period of risk (1980-1996) for human exposure to the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, commonly known as "mad cow" disease). His stay in the United States was too brief relative to what is known about the incubation period for variant CJD.

The third patient was born and raised in Saudi Arabia and has lived in the United States since late 2005. The patient occasionally stayed in the United States for up to 3 months at a time since 2001 and there was a shorter visit in 1989. The patient's onset of symptoms occurred in Spring 2006. In late November 2006, the Clinical Prion Research Team at the University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center confirmed the vCJD clinical diagnosis by pathologic study of adenoid and brain biopsy tissues. The patient has no history of receipt of blood, a past neurosurgical procedure, or residing in or visiting countries of Europe. Based on the patient's history, the occurrence of a previously reported Saudi case of vCJD attributed to likely consumption of BSE-contaminated cattle products in Saudi Arabia, and the expected greater than 7 year incubation period for food-related vCJD, this U.S. case-patient was most likely infected from contaminated cattle products consumed as a child when living in Saudi Arabia (1). The patient has no history of donating blood and the public health investigation has identified no known risk of transmission to U.S. residents from this patient.

Occurrence worldwide

From 1995 through August 2004, 147 human cases of vCJD were reported in the United Kingdom (UK), 7 in France, and 1 each in Canada, Ireland, Italy, and the United States. The patients from Canada, Ireland, and the United States had lived in the UK during a key exposure period of the UK population to the BSE agent. By year of onset, the incidence of vCJD in the UK appears to have peaked in 1999 and to have been declining thereafter. However, the future pattern of this epidemic, including whether a second wave of cases might occur among a large, genetically less susceptible subgroup of the population, remains uncertain.

From 1986 through 2001, more than 98% of BSE cases worldwide were reported from the UK, where the disease was first described. During this same period, the number of European countries reporting at least one indigenous BSE case increased from 4 through 1993 to 8 through 1998 to18 through 2001. During 2001-2003, three countries outside Europe (Canada, Japan, and Israel) reported their first indigenous BSE cases. The proportion of the annual total number of BSE cases worldwide reported outside the UK increased to more than 25% in 2000 and more than 55% in 2003. This increase reflected the declining large (more than 183,000 total cases) epidemic of BSE in the UK and the increasing number of other countries with improved surveillance and higher rates of BSE.

In 2003, only two countries, the UK and Portugal, reported a BSE incidence rate of more than 100 indigenous cases per million cattle more than 24 months of age. In 2003, the reported BSE rates per million cattle more than 24 months of age were 58 for the Republic of Ireland, 46 for Spain, 25 for Switzerland, 12 for France, 11 for Belgium and the Netherlands, 10 for Italy, 9 for Germany, and 7 for Slovakia. The reported rates for Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Japan, Poland, and Slovenia were between 0.3 and 6 cases per million. The reported BSE incidence rates, by country and year, are available on the Internet website of the Office International des Epizooties at http://www.oie.int/eng/info/en_esbincidence.htm. New information is being generated on a regular basis, and updated sources should be consulted.

In addition to the countries with indigenous cases of confirmed BSE in 2003, 6 countries previously had reported one or two BSE cases to the OIE; these countries include Austria, Finland, Greece, Israel, Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg. The European Union's committees on BSE risk assessment have also classified 18 other countries as likely to have BSE, including Albania, Andorra, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malta, Mexico, Romania, San Marino, South Africa, Turkey, and the United States.

The identification in 2003 of a BSE case in Canada, and the subsequent identification later that year of a BSE case in the United States that had been imported from Canada led to the concern that indigenous transmission of BSE may be occurring in North America. In response, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) implemented additional safeguards to minimize the risk for human exposure to BSE and on July 1, 2004, initiated a 12- to 18-month-long intensive testing program for BSE among cattle at relatively high risk for the disease (e.g., non-ambulatory cattle). Further details about this BSE surveillance effort in the United States, including test results, are available at http://www.aphis.usda.gov/lpa/issues/bse_testing/plan.html.

In 2003, a case of vCJD, which is now believed to have resulted from the receipt of transfused blood contaminated with the vCJD agent, was reported in a 62-year-old UK resident. In 2004, a second highly probable instance of transmission of the agent of vCJD through transfused blood was reported in the UK. In response, the British government extended earlier safeguards against transmission of vCJD via blood products and banned all persons receiving a blood transfusion after 1980 in the UK from subsequently donating blood. In January 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration published guidance outlining a geography-based donor deferral policy to reduce the risk of bloodborne transmission of vCJD in the United States. This guidance document included an appendix that listed European countries with BSE or a possible increased risk of BSE for use in determining blood donor deferrals. In addition to European countries cited above in the present chapter, other countries listed included Bosnia-Herzegovina, Liechtenstein, Norway, Sweden, and the former Yugoslavia. One deferral criterion was living cumulatively for 5 or more years in continental Europe from 1980 to the present. New information is regularly generated on the international BSE outbreak, and updated sources should be consulted, including the Internet website of the USDA at http://www.aphis.usda.gov/NCIE/country.html#BSE.

Evidence for Relationship with BSE (Mad Cow Disease)

Since 1996, evidence has been increasing for a causal relationship between ongoing outbreaks in Europe of a disease in cattle, called bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or 'mad cow' disease), and vCJD. There is now strong scientific evidence that the agent responsible for the outbreak of prion disease in cows, BSE, is the same agent responsible for the outbreak of vCJD in humans. Both disorders are invariably fatal brain diseases with unusually long incubation periods measured in years, and are caused by an unconventional transmissible agent. However, this evidence also suggests that the risk is low for having vCJD, even after consumption of contaminated product. In 1996, because of the emergence of vCJD in the United Kingdom, CDC enhanced its surveillance for CJD in the United States.

Risk Factors

Risk for Travelers

The current risk of acquiring vCJD from eating beef (muscle meat) and beef products produced from cattle in countries with at least a possibly increased risk of BSE cannot be determined precisely. If public health measures are being well implemented the current risk of acquiring vCJD from eating beef and beef products from these countries appears to be extremely small, although probably not zero. A rough estimate of this risk for the UK in the recent past, for example, was about 1 case per 10 billion servings. Among many uncertainties affecting such risk determinations are 1) the incubation period between exposure to the infective agent and onset of illness, 2) the appropriate interpretation and public health significance of the prevalence estimates of asymptomatic human vCJD infections, 3) the sensitivities of each country's surveillance for BSE and vCJD, 4) the compliance with and effectiveness of public health measures instituted in each country to prevent BSE contamination of human food, and 5) details about cattle products from one country distributed and consumed elsewhere. As of August 2006, despite the apparent exceedingly low risk of contracting vCJD through consumption of food in Europe, the US blood donor deferral criteria focuses on the time (cumulatively 5 years or more) that a person lived in continental Europe from 1980 through the present. In addition, these deferral criteria apply to persons who lived in the United Kingdom from 1980 through 1996.

Pathophysiology & Etiology

Natural History

Variant CJD (vCJD) is a rare, degenerative, fatal brain disorder in humans. Although experience with this new disease is limited, evidence to date indicates that there has never been a case of vCJD transmitted through direct contact of one person with another. However, a case of probable transmission of vCJD through transfusion of blood components from an asymptomatic donor who subsequently developed the disease has been reported.

Since variant CJD was first reported in 1996, a total of 200 patients with this disease from 11 countries have been identified. As of November 2006, variant CJD cases have been reported from the following countries: 164 from the United Kingdom, 21 from France, 4 from Ireland, 3 from the United States, 2 in the Netherlands, and one each from Canada, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, and Spain. Two of the three U.S. cases, two of the four cases from Ireland and the single cases from Canada and Japan were likely exposed to the BSE agent while residing in the United Kingdom. One of the 20 French cases may also have been infected in the United Kingdom.

There has never been a case of vCJD that did not have a history of exposure within a country where this cattle disease, BSE, was occurring.

It is believed that the persons who have developed vCJD became infected through their consumption of cattle products contaminated with the agent of BSE. There is no known treatment of vCJD and it is invariably fatal.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

vCJD Differs from Classic CJD

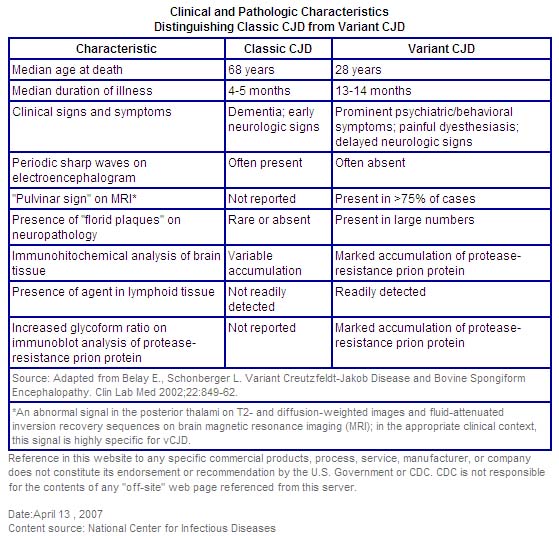

This variant form of CJD should not be confused with the classic form of CJD that is endemic throughout the world, including the United States. There are several important differences between these two forms of the disease. The median age at death of patients with classic CJD in the United States, for example, is 68 years, and very few cases occur in persons under 30 years of age. In contrast, the median age at death of patients with vCJD in the United Kingdom is 28 years.

vCJD can be confirmed only through examination of brain tissue obtained by biopsy or at autopsy, but a "probable case" of vCJD can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria developed in the United Kingdom.

The incubation period for vCJD is unknown because it is a new disease. However, it is likely that ultimately this incubation period will be measured in terms of many years or decades. In other words, whenever a person develops vCJD from consuming a BSE-contaminated product, he or she likely would have consumed that product many years or a decade or more earlier.

In contrast to classic CJD, vCJD in the United Kingdom predominantly affects younger people, has atypical clinical features, with prominent psychiatric or sensory symptoms at the time of clinical presentation and delayed onset of neurologic abnormalities, including ataxia within weeks or months, dementia and myoclonus late in the illness, a duration of illness of at least 6 months, and a diffusely abnormal non-diagnostic electroencephalogram.

The BSE epidemic in the United Kingdom reached its peak incidence in January 1993 at almost 1,000 new cases per week. The outbreak may have resulted from the feeding of scrapie-containing sheep meat-and-bone meal to cattle. There is strong evidence and general agreement that the outbreak was amplified by feeding rendered bovine meat-and-bone meal to young calves.

History and Symptoms

Patients with vCJD are typically much younger than those with sporadic disease. They may present with sensory disturbances and psychiatric problems. Paresthesias, dysarthria, gait disturbances, depression and anxiety are common findings, especially as disease progresses. Tissue diagnosis is required.

Treatment

Treatment of prion diseases remains supportive; no specific therapy has been shown to stop the progression of these diseases.

Primary Prevention

Public health control measures, such as surveillance, culling sick animals, or banning specified risk materials, have been instituted in many countries, particularly in those with indigenous cases of confirmed BSE, in order to prevent potentially BSE-infected tissues from entering the human food supply. The most stringent of these control measures, including a program that excluded all animals >30 months of age from the human food and animal feed supplies [the Over Thirty Month (OTM) rule], was applied in the UK and appeared to be highly effective. With the decrease in British BSE cases, the OTM rule was replaced in 2005 with a BSE testing regime, and in 2006, the ban on exports of British beef to other members of the European Union was lifted. In June 2000, the European Union Commission on Food Safety and Animal Welfare had strengthened the European Union's BSE control measures by requiring all member states to remove specified risk materials from animal feed and human food chains as of October 1, 2000; such bans had already been instituted in most member states.

To reduce any risk of acquiring vCJD from food, concerned travelers to Europe or other areas with indigenous cases of BSE may consider either avoiding beef and beef products altogether or selecting beef or beef products, such as solid pieces of muscle meat (rather than brains or beef products like burgers and sausages), that might have a reduced opportunity for contamination with tissues that may harbor the BSE agent. These measures, however, should be taken with the knowledge of the very low risk of disease transmission, particularly to older persons, as discussed above. Milk and milk products from cows are not believed to pose any risk for transmitting the BSE agent.

References

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/index.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/qa.htm#variant

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/factsheet_nvcjd.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/risk_travelers.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/epidemiology.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/vcjd/chart_percent_vcjd_cjd_deaths.htm

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D.