Sleep apnea

| Sleep apnea | |

| |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | G47.3 |

| ICD-9 | 780.57 |

| eMedicine | ped/2114 |

| MeSH | D012891 |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Sleep apnea |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Sleep apnea Most cited articles on Sleep apnea |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Sleep apnea |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Sleep apnea at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Sleep apnea at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Sleep apnea

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Sleep apnea Discussion groups on Sleep apnea Patient Handouts on Sleep apnea Directions to Hospitals Treating Sleep apnea Risk calculators and risk factors for Sleep apnea

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Sleep apnea |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [3]

For patient information click here

Overview

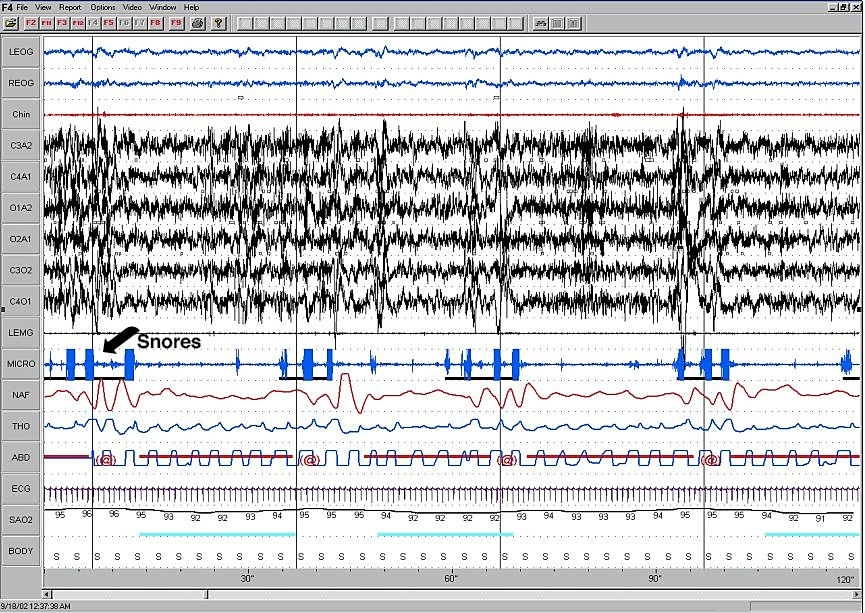

Sleep apnea, sleep apnoea or sleep apnœa is a sleep disorder characterized by pauses in breathing during sleep. These episodes, called apneas (literally, "without breath"), each last long enough so one or more breaths are missed, and occur repeatedly throughout sleep. The standard definition of any apneic event includes a minimum 10 second interval between breaths, with either a neurological arousal (3-second or greater shift in EEG frequency, measured at C3, C4, O1, or O2), or a blood oxygen desaturation of 3-4 percent or greater, or both arousal and desaturation. Sleep apnea is diagnosed with an overnight sleep test called a polysomnogram.

Clinically significant levels of sleep apnea are defined as 5 or more events of any type per hour of sleep time (from the polysomnogram). There are two distinct forms of sleep apnea: Central and Obstructive. Breathing is interrupted by the lack of effort in central sleep apnea; in obstructive sleep apnea, breathing is interrupted by a physical block to airflow despite effort. In mixed sleep apnea, there is a transition from central to obstructive features during the events themselves.

Regardless of type, the individual with sleep apnea is rarely aware of having difficulty breathing, even upon awakening. Sleep apnea is recognized as a problem by others witnessing the individual during episodes or is suspected because of its effects on the body (sequelae). Symptoms may be present for years, even decades without identification, during which time the sufferer may become conditioned to the daytime sleepiness and fatigue associated with significant levels of sleep disturbance.

Obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is not only much more frequent than central sleep apnea, it is a common condition in many parts of the world. If studied carefully in a sleep lab by polysomnography, approximately 1 in 5 American adults has at least mild OSA. [1] Since the muscle tone of the body ordinarily relaxes during sleep, and since, at the level of the throat, the human airway is composed of walls of soft tissue, which can collapse, it is easy to understand why breathing can be obstructed during sleep. Although many individuals experience episodes of obstructive sleep apnea at some point in life, a much smaller percentage of people are afflicted with chronic severe obstructive sleep apnea.

Normal sleep/wakefulness in adults has distinct stages numbered 1 to 4, REM sleep, and wake. The deeper stages (3 to 4) are required for the physically restorative effects of sleep and in pre-adolescents are the focus of release for human growth hormone. Stages 2 and REM, which combined are 70% of an average person's total sleep time, are more associated with mental recovery and maintenance. During REM sleep in particular, muscle tone of the throat and neck, as well as the vast majority of all skeletal muscles, is almost completely attenuated, allowing the tongue and soft palate/oropharynx to relax, and in the case of sleep apnea, to impede the flow of air to a degree ranging from light snoring to complete collapse. In the cases where airflow is reduced to a degree where blood oxygen levels fall, or the physical exertion to breathe is too great, neurological mechanisms trigger a sudden interruption of sleep, called a neurological arousal. These arousals may or may not result in complete awakening, but can have a significant negative effect on the restorative quality of sleep. In significant cases of obstructive sleep apnea, one consequence is sleep deprivation due to the repetitive disruption and recovery of sleep activity. This sleep interruption in stages 3 and 4 (also collectively called slow-wave sleep), can interfere with normal growth patterns, healing, and immune response, especially in children and young adults.

Many people experience elements of obstructive sleep apnea for only a short period of time. This can be the result of an upper respiratory infection that causes nasal congestion, along with swelling of the throat, or tonsillitis that temporarily produces very enlarged tonsils. The Epstein-Barr virus, for example, is known to be able to dramatically increase the size of lymphoid tissue during acute infection, and obstructive sleep apnea is fairly common in acute cases of severe infectious mononucleosis. Temporary spells of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome may also occur in individuals who are under the influence of a drug (such as alcohol) that may relax their body tone excessively and interfere with normal arousal from sleep mechanisms.

Laboratory findings

Polysomnography

Results of polysomnography in obstructive sleep apnea show pauses in breathing. As in central apnea, pauses are followed by a relative decrease in blood oxygen and an increase in the blood carbon dioxide. Whereas in central sleep apnea the body's motions of breathing stop, in obstructive sleep apnea the chest not only continues to make the movements of inhalation, the movements typically become even more pronounced. Monitors for airflow at the nose and mouth show the dynamics of airflow, but efforts to breathe are not only present, they are often exaggerated. The chest muscles and diaphragm contract and the entire body may thrash and struggle.

Obstructive sleep apnea is the most common category of sleep-disordered breathing. The prevalence of OSA among the adult population in western Europe and North America has not been confidently established, but in the mid-1990s was estimated to be 3-4% of women and 6-7% of men.

An "event" can be either an apnea, characterised by complete cessation of airflow for at least 10 seconds, or a hypopnea in which airflow decreases by 50 percent for 10 seconds or decreases by 30 percent if there is an associated decrease in the oxygen saturation or an arousal from sleep (American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force, 1999). To grade the severity of sleep apnea the number of events per hour is reported as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). An AHI of less than 5 is considered normal. An AHI of 5-15 is mild; 15-30 is moderate and more than 30 events per hour characterizes severe sleep apnea

Home oximetry

In patients who are at high likelihood of having OSA, a randomized controlled trial found that home oximetry may be adequate and easier to obtain than formal polysomnography[2]. High probability patients were indentified by Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) of 10 or greater and a Sleep Apnea Clinical Score (SACS) of 15 or greater.[3]

Populations at risk

Individuals with decreased muscle tone, increased soft tissue around the airway, and structural features that give rise to a narrowed airway are at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Men, whose anatomy is typified by increased body mass in the torso and neck, are more typical sleep apnea sufferers, especially through middle age and older. Adult women suffer typically less frequently and to a lesser degree than men do, owing partially to physiology, but possibly to emerging links to levels of progesterone. Prevalence in post-menopausal women approaches that of men in the same age range.

Adults

In adults, the most typical individual with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is obese, with particular heaviness at the face and neck. The hallmark symptom of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in adults is excessive daytime sleepiness. Typically, an adult or adolescent with severe long-standing obstructive sleep apnea will fall asleep for very brief periods in the course of usual daytime activities if given any opportunity to sit or rest. This behavior may be quite dramatic, sometimes occurring during conversations with others at social gatherings.

Children

Although this so called "hyper-somnolence" (excessive sleepiness) may also occur in children, it is not at all typical of younger children with sleep apnea. Toddlers and young children with severe obstructive sleep apnea instead ordinarily behave as if "over-tired" or "hyper". Adults and children with very severe obstructive sleep apnea also differ in typical body habitus. Adults are generally heavy, with particularly short and heavy necks. Young children, on the other hand, are generally not only thin but may have "failure to thrive", where growth is reduced. Poor growth occurs for two reasons: the work of breathing is high enough so that calories are burned at high rates even at rest, and the nose and throat are so obstructed that eating is both tasteless and physically uncomfortable. Obstructive sleep apnea in children, unlike adults, is almost always caused by obstructive tonsils and adenoids and is usually cured with tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.

This problem can also be caused by excessive weight. The symptoms are more like the symptoms adults feel; restlessness, exhaustion, and more.

Common signs and symptoms

(The signs and symptoms that follow apply to both adults and children suffering with sleep apnea)

Additional signs of obstructive sleep apnea include restless sleep, and loud snoring (with periods of silence followed by gasps). Other symptoms are non-specific: morning headaches, trouble concentrating, irritability, forgetfulness, mood or behavior changes, decreased sex drive, increased heart rate, anxiety, depression, increased frequency of urination, nocturia (getting up during the night to urinate), esophageal reflux and heavy sweating at night.

The most serious consequence of obstructive sleep apnea is to the heart. In severe and prolonged cases, there are increases in pulmonary pressures that are transmitted to the right side of the heart. This can result in a severe form of congestive heart failure (cor pulmonale).

Craniofacial syndromes

There are patterns of unusual facial features that occur in recognizable syndromes. Some of these craniofacial syndromes are genetic, others are from unknown causes. In many craniofacial syndromes, the features that are unusual involve the nose, mouth and jaw, or resting muscle tone, and put the individual at risk for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Down Syndrome is one such syndrome. In this chromosomal abnormality, several features combine to make the presence of obstructive sleep apnea more likely. The specific features in Down Syndrome that predispose to obstructive sleep apnea include: relatively low muscle tone, narrow nasopharynx, and large tongue. Obesity and enlarged tonsils and adenoids, conditions that occur commonly in the western population, are much more likely to be obstructive in a person with these features than without them. Obstructive sleep apnea does occur even more frequently in people with Down Syndrome than in the general population. A little over 50% of all people with Down Syndrome suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (de Miguel-Díez, et al 2003), and some physicians advocate routine testing of this group (Shott, et al 2006).

In other craniofacial syndromes, the abnormal feature may actually improve the airway- but its correction may put the person at risk for obstructive sleep apnea after surgery, when it is modified. Cleft palate syndromes are such an example. During the newborn period, all humans are obligate nasal breathers. The palate is both the roof of the mouth and the floor of the nose. Having an open palate may make feeding difficult, but generally does not interfere with breathing, in fact - if the nose is very obstructed an open palate may relieve breathing. There are a number of clefting syndromes in which the open palate is not the only abnormal feature, additionally there is a narrow nasal passage - which may not be obvious. In such individuals, closure of the cleft palate- whether by surgery or by a temporary oral appliance, can cause the onset of obstruction.

Skeletal advancement in an effort to physically increase the pharyngeal airspace is often an option for craniofacial patients with upper airway obstruction and small lower jaws (mandibles). These syndromes include Treacher Collins Syndrome and Pierre Robin Sequence. Mandibular advancement surgery is often just one of the modifications needed to improve the airway, others may include reduction of the tongue, tonsillectomy or modified uvulopalatoplasty.

Pharyngeal flap surgery may cause obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea is a serious complication that seems to be most frequently associated with pharyngeal flap surgery, compared to other procedures for treatment of velopharyngeal inadequacy (VPI).[4] In OSA, recurrent interruptions of respiration during sleep are associated with temporary airway obstruction. Following pharyngeal flap surgery, depending on size and position, the flap itself may have an “obturator” or obstructive effect within the pharynx during sleep, blocking ports of airflow and hindering effective respiration.[5][6] There have been documented instances of severe airway obstruction, and reports of post-operative OSA continue to increase as healthcare professionals (i.e. physicians, speech language pathologists) become more educated about this possible dangerous condition.[7] Subsequently, in clinical practice, concerns of OSA have matched or exceeded interest in speech outcomes following pharyngeal flap surgery.

The surgical treatment for velopalatal insufficiency may cause obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. When velopalatal insufficiency is present, air leaks into the nasopharynx even when the soft palate should close off the nose. A simple test for this condition can be made by placing a tiny mirror at the nose, and asking the subject to say "P". This p sound, a plosive, is normally produced with the nasal airway closed off - all air comes out of the pursed lips, none from the nose. If it is impossible to say the sound without fogging a nasal mirror, there is an air leak - reasonable evidence of poor palatal closure. Speech is often unclear due to inability to pronounce certain sounds. One of the surgical treatments for velopalatal insufficiency involves tailoring the tissue from the back of the throat and using it to purposefully cause partial obstruction of the opening of the nasopharynx. This may actually cause obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in susceptible individuals, particularly in the days following surgery, when swelling occurs (see below: Special Situation: Anesthesia and Surgery)

| AHI | Rating |

|---|---|

| <5 | Normal |

| 5-15 | Mild |

| 15-30 | Moderate |

| >30 | Severe |

Treatment

There are a variety of treatments for obstructive sleep apnea, depending on an individual’s medical history, the severity of the disorder and, most importantly, the specific cause of the obstruction.

In acute infectious mononucleosis, for example, although the airway may be severely obstructed in the first 2 weeks of the illness, the presence of lymphoid tissue (suddenly enlarged tonsils and adenoids) blocking the throat is usually only temporary. A course of anti-inflammatory steroids such as prednisone (or another kind of glucocorticoid drug) is often given to reduce this lymphoid tissue. Although the effects of the steroids are short term, in most affected individuals, the tonsillar and adenoidal enlargement are also short term, and will be reduced on its own by the time a brief course of steroids is completed. In unusual cases where the enlarged lymphoid tissue persists after resolution of the acute stage of the Epstein-Barr infection, or in which medical treatment with anti-inflammatory steroids does not adequately relieve breathing, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy may be urgently required.

Most children with obstructive sleep apnea have the problem on the basis of chronically enlarged tonsils and adenoids. In these children, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy is curative. The operation may be far from trivial, however, in the worst cases, in which growth is reduced and abnormalities of the right heart may have developed. Even in these extreme cases, however, the surgery tends to cure not only the apnea and upper airway obstruction - but to allow subsequent normal growth and development. Once the high end-expiratory pressures are relieved, the cardiovascular complications reverse themselves. The postoperative period in these children requires special precautions (see surgery and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome below).

The treatment for obstructive sleep apnea in the case of adults with poor oropharyngeal airways secondary to heavy upper body type is varied. Unfortunately, in this most common type of obstructive sleep apnea, unlike some of the cases discussed above, reliable cures are not the rule.

Some treatments involve lifestyle changes, such as avoiding alcohol and medications that relax the central nervous system (for example, sedatives and muscle relaxants), losing weight, and quitting smoking. Some people are helped by special pillows or devices that keep them from sleeping on their backs, or oral appliances to keep the airway open during sleep. If these conservative methods are inadequate, doctors often recommend continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), in which a face mask is attached to a tube and a machine that blows pressurized air into the mask and through the airway to keep it open. There are also surgical procedures that can be used to remove and tighten tissue and widen the airway, but the success rate is not high. Some individuals may need a combination of therapies to successfully treat their sleep apnea.

Physical intervention

The most widely used current therapeutic intervention is positive airway pressure whereby a breathing machine pumps a controlled stream of air through a mask worn over the nose, mouth, or both. The additional pressure splints or holds open the relaxed muscles, just as air in a balloon inflates it. There are several variants:

- (CPAP), or continuous positive airway pressure, in which a controlled air compressor generates an airstream at a constant pressure. This pressure is prescribed by the patient's physician, based on an overnight test or titration. Newer CPAP models are available which slightly reduce pressure upon exhalation to increase patient comfort and compliance. CPAP is the most common treatment for obstructive sleep apnea.

- (VPAP), or variable positive airway pressure, also known as bilevel or BiPAP, uses an electronic circuit to monitor the patient's breathing, and provides two different pressures, a higher one during inhalation and a lower pressure during exhalation. This system is more expensive, and is sometimes used with patients who have other coexisting respiratory problems and/or who find breathing out against an increased pressure to be uncomfortable or disruptive to their sleep.

- (APAP), or automatic positive airway pressure, is the newest form of such treatment. An APAP machine incorporates pressure sensors and a computer which continuously monitors the patient's breathing performance. It adjusts pressure continuously, increasing it when the user is attempting to breathe but cannot, and decreasing it when the pressure is higher than necessary. Although FDA approved, these devices are still considered experimental by many, and are not covered by most insurance plans.

A second type of physical intervention, a Mandibular advancement splint (MAS), is sometimes prescribed for mild or moderate sleep apnea sufferers. The device is a mouthguard similar to those used in sports to protect the teeth. For apnea patients, it is designed to hold the lower jaw slightly down and forward relative to the natural, relaxed position. This position holds the tongue farther away from the back of the airway, and may be enough to relieve apnea or improve breathing for some patients. The FDA accepts only 16 oral appliances for the treatment of sleep apnea. A listing is available at their website

Oral appliance therapy is less effective than CPAP, but is more 'user friendly'. Side-effects are common, but rarely is the patient aware of them.

Pharmaceuticals

There are no effective drug-based treatment for obstructive sleep apnea.

Oral administration of the methylxanthine theophylline (chemically similar to caffeine) can reduce the number of episodes of apnea, but can also produce side effects such as palpitations and insomnia. Theophylline is generally ineffective in adults with OSA, but is sometimes used to treat central sleep apnea (see below), and infants and children with apnea.

When other treatments do not completely treat the OSA, drugs are sometimes prescribed to treat a patient's daytime sleepiness or somnolence. These range from stimulants such as amphetamines to modern anti-narcoleptic medicines. The anti-narcoleptic modafinil is seeing increased use in this role as of 2004.

In most cases, weight loss will reduce the number and severity of apnea episodes. In the morbidly obese, a major loss of weight (such as what occurs after bariatric surgery) can sometimes cure the condition.

Neurostimulation

Many researchers believe that OSA is at root a neurological condition, in which nerves that control the tongue and soft palate fail to sufficiently stimulate those muscles, leading to over-relaxation and airway blockage. A few experiments and trial studies have explored the use of pacemakers and similar devices, programmed to detect breathing effort and deliver gentle electrical stimulation to the muscles of the tongue.

This is not a common mode of treatment for OSA patients as of 2004, but it is an active field of research.

Surgical intervention

A number of different surgeries are available to improve the size or tone of a patient's airway. For decades, tracheostomy was the only effective treatment for sleep apnea. It is used today only in rare, intractable cases that have withstood other attempts at treatment. Modern operations employ one or more of several options, tailored to each patient's needs. Long term success rates are low, resulting in most doctors favoring CPAP.

- Nasal surgery, including turbinectomy (removal or reduction of a nasal turbinate), or straightening of the nasal septum, in patients with nasal obstruction or congestion which reduces airway pressure and complicates OSA.

- Tonsilectomy and/or adenoidectomy in an attempt to increase the size of the airway.

- Removal or reduction of parts of the soft palate and some or all of the uvula, such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) or laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP). Modern variants of this procedure sometimes use radiofrequency waves to heat and remove tissue.

- Reduction of the tongue base, either with laser excision or radiofrequency ablation.

- Genioglossus Advancement, in which a small portion of the lower jaw that attaches to the tongue is moved forward, to pull the tongue away from the back of the airway.

- Hyoid Suspension, in which the hyoid bone in the neck, another attachment point for tongue muscles, is pulled forward in front of the larynx.

- Maxillomandibular advancement (MMA). A more invasive surgery usually only tried in difficult cases where other surgeries have not relieved the patient's OSA, or where an abnormal facial structure is suspected as a root cause. In MMA, the patient's upper and lower jaw are detached from the skull, moved forward, and reattached with pins and/or plates.[8]

- Pillar procedure, three small inserts are injected into the soft palate to offer support, potentially reducing snoring in mild to moderate sleep apnea[9]

Special situation: surgery and anesthesia in patients with sleep apnea syndrome

Many drugs and agents used during surgery to relieve pain and depress consciousness remain in the body at low amounts for hours or even days afterwards. In an individual with either central, obstructive or mixed sleep apnea, these low doses may be enough to cause life-threatening irregularities in breathing.

Use of analgesics and sedatives in these patients postoperatively should therefore be minimized or avoided.

Surgery on the mouth and throat, as well as dental surgery and procedures, can result in postoperative swelling of the lining of the mouth and other areas that affect the airway. Even when the surgical procedure is designed to improve the airway, such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy or tongue reduction - swelling may negate some of the effects in the immediate postoperative period.

Individuals with sleep apnea generally require more intensive monitoring after surgery for these reasons.

Alternative treatments

Breathing exercises, such as those used in Yoga, the Buteyko method, or didgeridoo playing can be effective. There are muscles which act to tension and open the airway during each inspiration. Exercises can, in some cases, restore sufficient function to these muscles to prevent or reduce apnea.

A program which uses specialized "singing" exercises to tone the throat, in particular, the soft palate, tongue and nasaopharynx, is 'Singing for Snorers' by Alise Ojay. Dr. Elizabeth Scott, a medical doctor living in Scotland, had experimented with singing exercises and found considerable success, as reviewed in her book The Natural Way to Stop Snoring (London: Orion 1995) but had been unable to carry out a clinical trial. Alise Ojay, a choir director singer and composer, began researching the possibility of using singing exercises to help a friend with snoring, and came across Dr. Scott's work. In 1999, as an Honorary Research Fellow with the support of the Department of Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter, Alise conducted the first trial of singing exercises to reduce snoring which she published with Edzard Ernst, "Can singing exercises reduce snoring? A pilot study." Complement Ther Med 2000; 8(3): 151-156. The results were described by Ojay as promising and after two years of investigations, she designed the 'Singing for Snorers' program in 2002.

The independent nonprofit UK consumer advocacy group Which? reviewed Singing for Snorers. Their physician Dr. Williams "feels the company is ethical in ‘offering aims not claims’ until research is complete." and the review stated that "Combining the programme with diet and exercise, the snorer in our test couple found real improvements in the volume and frequency of his snoring after six weeks. His partner is sleeping better, too."[10] In the case of snorers who also have sleep apnea, there is anecdotal evidence from some of the users of Ojay's program, as she reports on her page[11], as reported by Charley Hupp, who flew to the UK to personally thank her, on his web page[12] and as reported by one user in the UK on the discussion forum of the British Snoring and Sleep Apnoea Association. This person, Ken, reports that sleep tests before and after the program shows a significant effect: "my apnoeas had gone down from 35 to 0.8 per hour."[13]

Position treatments

One of the best treatments is merely to sleep at a 30 degree angle[14] or higher, as if in a recliner. Doing so helps prevent gravity from collapsing the airway. Lateral positions (sleeping on your side), as opposed to supine positions (sleeping on your back), are also recommended as a treatment for sleep apnea,[15][16][17] largely because the effect of gravity is not as strong to collapse the airway in the lateral position. Nonetheless, sleeping at a 30 degree angle is a superior sleep position compared to either a supine or lateral position.[18] A 30 degree position can be achieved by sleeping in a recliner, buying an adjustable bed, or buying a bed wedge to place under the mattress. This approach can easily be used in combination with other treatments and may be particularly effective in very obese people.

Prognosis

Although it takes some trial and error, most patients find a combination of treatments which reduce apnea events and improve their overall health, energy, and well-being. Without treatment, the sleep deprivation and lack of oxygen caused by sleep apnea increases health risks such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes, clinical depression,[19] weight gain and obesity.

The most serious consequence of untreated obstructive sleep apnea is to the heart. In severe and prolonged cases, there are increases in pulmonary pressures that are transmitted to the right side of the heart. This can result in a severe form of congestive heart failure (cor pulmonale).

Elevated arterial pressure (commonly called high blood pressure) can be a consequence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.[20] When high blood pressure is caused by OSA, it is distinctive in that, unlike most cases of high blood pressure (so-called essential hypertension), the readings do not drop significantly when the individual is sleeping.[21] Stroke is associated with obstructive sleep apnea.[22] Sleep apnea sufferers also have a 30% higher risk of heart attack or death than those unaffected.[23]

Many studies indicate that it is the effect of the "fight or flight" response on the body that happens with each apneic event that increases these risks. The fight or flight response causes many hormonal changes in the body; those changes, coupled with the low oxygen saturation level of the blood, cause damage to the body over time.[24][25][26][27]

Epidemiology

OSA is a common condition in many parts of the world. If studied carefully in a sleep lab by polysomnography, approximately 1 in 5 American adults has at least mild OSA.[1] OSA is more frequent than central sleep apnea.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK (2003). "Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease". Journal of the American Medical Association. 290 (14): 1906–14. PMID 14532320. Unknown parameter

|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Mulgrew AT, Fox N, Ayas NT, Ryan CF (2007). "Diagnosis and initial management of obstructive sleep apnea without polysomnography: a randomized validation study". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (3): 157–66. PMID 17283346.

- ↑ Flemons WW, Whitelaw WA, Brant R, Remmers JE (1994). "Likelihood ratios for a sleep apnea clinical prediction rule". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 150 (5 Pt 1): 1279–85. PMID 7952553.

- ↑ Sloan, G.M. (2000). Posterior pharyngeal flap and sphincter pharyngoplasty: The state of the art. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 37(2), 112-122.

- ↑ Pugh, M.B. et al. (2000). Apnea. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary (27th ed.) Retrieved June 18, 2006 from STAT!Ref Online Medical Library database.

- ↑ Liao, Y., Noordhoff, M.S., Huang, C., Chen, P.K.T., Chen N., Yun, C. et al. (2004). Comparison of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children with cleft palate following Furlow palatoplasty or pharyngeal flap for velopharyngeal insufficiency. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 41(2), 152-156.

- ↑ Peterson-Falzone, S.J., Hardin-Jones, M.A., & Karnell, M.P. (2001). Cleft Palate Speech (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

- ↑ Li K, Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C (2000). "Maxillomandibular advancement for persistent obstructive sleep apnea after phase I surgery in patients without maxillomandibular deficiency". Laryngoscope. 110 (10 Pt 1): 1684–8. PMID 11037825.

- ↑ . "Pillar procedure". snoring.com.

- ↑ Snoring remedies Which? snoring remedy user trial

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Post subject: Singing for Snorers

- ↑ Effects of sleep posture on upper airway stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea - Neill et al. 155 (1): 199 - American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

- ↑ The Study Of The Influence Of Sleep Position On Sleep Apnea

- ↑ Positioner-a method for preventing sleep apnea

- ↑ Lateral sleeping position reduces severity of cent...[Sleep. 2006] - PubMed Result

- ↑ Effects of sleep posture on upper airway stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea - Neill et al. 155 (1): 199 - American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

- ↑ Schröder CM, O'Hara R (2005). "Depression and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)". Ann Gen Psychiatry. 4: 13. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-4-13. PMID 15982424.

- ↑ Silverberg DS, Iaina A and Oksenberg A (2002). "Treating Obstructive Sleep Apnea Improves Essential Hypertension and Quality of Life". American Family Physicians. 65 (2): 229–36. PMID 11820487. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Grigg-Damberger M. (2006-02). "Why a polysomnogram should become part of the diagnostic evaluation of stroke and transient ischemic attack". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 23 (1): 21–38. PMID 16514349. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ H. Klar Yaggi, M.D., M.P.H. (November 10, 2005). "Obstructive Sleep Apnea as a Risk Factor for Stroke and Death". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (Number 19): 2034–2041. PMID 16282178. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ N.A. Shah, M.D., N.A. Botros, M.D., H.K. Yaggi, M.D., M., V. Mohsenin, M.D., New Haven, CT (May 20, 2007). "Sleep Apnea Increases Risk of Heart Attack or Death by 30%". American Thoracic Society.

- ↑ www.yale.edu

- ↑ www.sciencedaily.com

- ↑ http://www.schlaflabor-breisgau.de/Bild_gif/Peppard.pdf

- ↑ www.sciencedaily.com

References

- Maninder Kalra (March 2007). "Genetic susceptibility to obstructive sleep apnea in the obese child". Sleep Medicine. 8 (2): 169–175. PMID 17275401. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force (1999). "Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research". Sleep. 22 (5): 667–89. PMID 10450601.

- Bell, R. B. (2001). "Skeletal advancement for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children". Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 38 (2): 147–54. Unknown parameter

|coauthor=ignored (help) - Caples S, Gami A, Somers V (2005). "Obstructive sleep apnea". Ann Intern Med. 142 (3): 187–97. PMID 15684207.

- Cohen, M. M. J. (1992). "Upper and lower airway compromise in the Apert syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 44: 90–93. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - de Miguel-Díez J, Villa-Asensi J, Alvarez-Sala J (2003). "Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in children with Down syndrome: polygraphic findings in 108 children" (PDF). Sleep. 26 (8): 1006–9. PMID 14746382.

- Mathur R, Douglas N (1994). "Relation between sudden infant death syndrome and adult sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome". Lancet. 344 (8925): 819–20. PMID 7916096.

- Mortimore I, Douglas N (1997). "Palatal muscle EMG response to negative pressure in awake sleep apneic and control subjects". Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 156 (3 Pt 1): 867–73. PMID 9310006.

- Perkins, J. A. (1997). "Airway management in children with craniofacial anomalies". Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 34 (2): 135–40. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Sculerati N. (1998 December). "Airway management in children with major craniofacial anomalies". Laryngoscope. 108 (12): 1806–12. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Shepard, J. W. (1990). "Localization of upper airway collapse during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea". American Review of Respiratory Disorders. 141: 1350–55. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Sher, A. (1990). Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a complex disorder of the upper airway. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 24, 600.

- Shott S, Amin R, Chini B, Heubi C, Hotze S, Akers R (2006). "Obstructive sleep apnea: Should all children with Down syndrome be tested?". Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 132 (4): 432–6. PMID 16618913.

- Shouldice RB, O'Brien LM, O'Brien C, de Chazal P, Gozal D, Heneghan C (2004). "Detection of obstructive sleep apnea in pediatric subjects using surface lead electrocardiogram features". Sleep. 27 (4): 784–92. PMID 15283015.

- Slovis B. & Brigham K. (2001). "Disordered Breathing". In ed Andreoli T. E. Cecil Essentials of Medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. pp210–211.

- Strollo P, Rogers R (1996). "Obstructive sleep apnea". N Engl J Med. 334 (2): 99–104. PMID 8531966.

- Sullivan C, Issa F, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L (1981). "Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares". Lancet. 1 (8225): 862–5. PMID 6112294.

External links

- American Sleep Apnea Association

- Sleep Apnea: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Differential Diagnosis of Sleep apnea Treatment

- Mayo Clinic Discovers New Type of Sleep Apnea, Mayo Clinic, September 1, 2006.

- Your Guide To Healthy Sleep, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- Non-profit Sleep Apnea Studies forum

- Apnea Board - non-profit Sleep Apnea info site & forum

- Sleep Apnea The Merck Manual

Template:Diseases of the nervous system

Template:SleepSeries2

Template:SIB

da:Søvnapnø de:Schlafapnoe-Syndrom et:Uneapnoe el:Άπνοια ύπνου id:Sleep apnea it:Apnea nel sonno ml:കൂര്ക്കം വലി nl:Slaapapneu no:Søvnapné nn:Søvnapné fi:Uniapnea sv:Sömnapné

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 errors: dates

- Pages using citations with accessdate and no URL

- CS1 maint: Date and year

- CS1 maint: Extra text

- Abnormal respiration

- Sleep

- Sleep disorders

- Sleep physiology

- Medical conditions related to obesity

- Pulmonology

- Cardiology

- Signs and symptoms

- Primary care