Radiation injury

| Radiation injury |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Radiation injury |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Radiation injury Most cited articles on Radiation injury |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Radiation injury |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Radiation injury at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Radiation injury Clinical Trials on Radiation injury at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Radiation injury NICE Guidance on Radiation injury

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Radiation injury Discussion groups on Radiation injury Patient Handouts on Radiation injury Directions to Hospitals Treating Radiation injury Risk calculators and risk factors for Radiation injury

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Radiation injury |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Injury to the skin and underlying tissues from acute exposure to a large external dose of radiation is referred to as cutaneous radiation injury (CRI). Acute radiation syndrome (ARS) 1 will usually be accompanied by some skin damage; however, CRI can occur without symptoms of ARS. This is especially true with acute exposures to beta radiation or low-energy x-rays, because beta radiation and low-energy x-rays are less penetrating and less likely to damage internal organs than gamma radiation is. CRI can occur with radiation doses as low as 2 Gray (Gy) or 200 rads 2 and the severity of CRI symptoms will increase with increasing doses. Most cases of CRI have occurred when people inadvertently came in contact with unsecured radiation sources from food irradiators, radiotherapy equipment, or well depth gauges. In addition, cases of CRI have occurred in people who were overexposed to x-radiation from fluoroscopy units.

Early signs and symptoms of CRI are itching, tingling, or a transient erythema or edema without a history of exposure to heat or caustic chemicals. Exposure to radiation can damage the basal cell layer of the skin and result in inflammation, erythema, and dry or moist desquamation. In addition, radiation damage to hair follicles can cause epilation. Transient and inconsistent erythema (associated with itching) can occur within a few hours of exposure and be followed by a latent, symptom-free phase lasting from a few days to several weeks. After the latent phase, intense reddening, blistering, and ulceration of the irradiated site are visible. Depending on the radiation dose, a third and even fourth wave of erythema are possible over the ensuing months or possibly years.

In most cases, healing occurs by regenerative means; however, large radiation doses to the skin can cause permanent hair loss, damaged sebaceous and sweat glands, atrophy, fibrosis, decreased or increased skin pigmentation, and ulceration or necrosis of the exposed tissue.

With CRI, it is important to keep the following things in mind:

- The visible skin effects depend on the magnitude of the dose as well as the depth of penetration of the radiation.

- Unlike the skin lesions caused by chemical or thermal damage, the lesions caused by radiation exposures do not appear for hours to days following exposure, and burns and other skin effects tend to appear in cycles.

- The key treatment issues with CRI are infection and pain management.

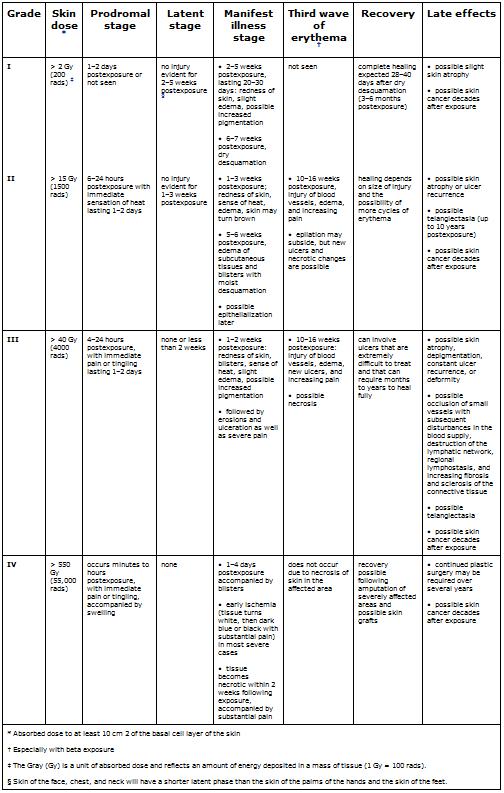

Stages and Grades of CRI

CRI will progress over time in stages and can be categorized by grade, with characteristics of the stages varying by grade of injury, as shown in Table 1. Appendix A gives a detailed description of the various skin responses to radiation, and Appendix B provides color photographs of examples of some of these responses.

Prodromal stage (within hours of exposure)—This stage is characterized by early erythema (first wave of erythema), heat sensations, and itching that define the exposure area. The duration of this stage is from 1 to 2 days.

Latent stage (1–2 days postexposure)—No injury is evident. Depending on the body part, the larger the dose, the shorter this period will last. The skin of the face, chest, and neck will have a shorter latent stage than will the skin of the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet.

Manifest illness stage (days to weeks postexposure)—The basal layer is repopulated through proliferation of surviving clonogenic cells. This stage begins with main erythema (second wave), a sense of heat, and slight edema, which are often accompanied by increased pigmentation. The symptoms that follow vary from dry desquamation or ulceration to necrosis, depending on the severity of the CRI (see Table 1).

Third wave of erythema (10–16 weeks postexposure, especially after beta exposure)—The exposed person experiences late erythema, injury to blood vessels, edema, and increasing pain. A distinct bluish color of the skin can be observed. Epilation may subside, but new ulcers, dermal necrosis, and dermal atrophy (and thinning of the dermis layer) are possible.

Late effects (months to years postexposure; threshold dose ~10 Gy or 1000 rads)—Symptoms can vary from slight dermal atrophy (or thinning of dermis layer) to constant ulcer recurrence, dermal necrosis, and deformity. Possible effects include occlusion of small blood vessels with subsequent disturbances in the blood supply (telangiectasia); destruction of the lymphatic network; regional lymphostasis; and increasing invasive fibrosis, keratosis, vasculitis, and subcutaneous sclerosis of the connective tissue. Pigmentary changes and pain are often present. Skin cancer is possible in subsequent years.

Recovery (months to years)

Patient Management

Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of CRI are as follows:

- Intensely painful burn-like skin injuries (including itching, tingling, erythema, or edema) without a history of exposure to heat or caustic chemicals

- Note : Erythema will not be seen for hours to days following exposure, and its appearance is cyclic.

- Epilation

- A tendency to bleed

- Possible signs and symptoms of ARS

As mentioned previously, local injuries to the skin from acute radiation exposure evolve slowly over time, and symptoms may not manifest for days to weeks after exposure. Consider CRI in the differential diagnosis if the patient presents with a skin lesion without a history of chemical or thermal burn, insect bite, or skin disease or allergy. If the patient gives a history of possible radiation exposure (such as from a radiography source, x-ray device, or accelerator) or a history of finding and handling an unknown metallic object, note the presence of any of the following: erythema, blistering, dry or wet desquamation, epilation, ulceration.

Regarding lesions associated with CRI be aware that,

- days to weeks may pass before lesions appear;

- unless patients are symptomatic, they will not require emergency care; and

- lesions can be debilitating and life threatening after several weeks.

Medical follow-up is essential, and victims should be cautioned to avoid trauma to the involved areas.

Initial Treatment

Localized injuries should be treated symptomatically as they occur, and radiation injury experts should be consulted for detailed information. Such information can be obtained from the Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site (REAC/TS) at www.orau.gov/reacts/ or (865) 576-1005.

As with ARS, if the patient also has other trauma, wounds should be closed, burns covered, fractures reduced, surgical stabilization performed, and definitive treatment given within the first 48 hours after injury. After 48 hours, surgical interventions should be delayed until hematopoietic recovery has occurred.

A baseline CBC and differential should be taken and repeated in 24 hours. Because cutaneous radiation injury is cyclic, areas of early erythema should be noted and recorded. These areas should also be sketched and photographed, if possible, ensuring that the date and time are recorded. The following should be initiated as indicated:

- Supportive care in a clean environment (a burn unit if one is available)

- Prevention and treatment of infections

- Use of the following:

- Medications to reduce inflammation, inhibit protealysis, relieve pain, stimulate regeneration, and improve circulation

- Anticoagulant agents for widespread and deep injury

- Pain management

- Psychological support

Recommendations for Treatment by Stage

The following recommendations for treatment by stage of the illness were obtained by summarizing recommendations from Ricks et al. (226) and Gusev et al. (231), but they do not represent official recommendations of CDC.

- Prodromal Stage —Use antihistamines and topical antipruriginous preparations, which act against itch and also might prevent or attenuate initiation of the cycle that leads to the manifestation stage. Anti-inflammatory medications such as corticosteroids and topical creams, as well as slight sedatives, may prove useful.

- Latent Stage —Continue anti-inflammatory medications and sedatives. At midstage, use proteolysis inhibitors, such as Gordox®.

- Manifestation Stage —Use repeated swabs, antibiotic prophylaxis, and anti-inflammatory medications, such as Lioxasol®, to reduce bacterial, fungal, and viral infections

- Apply topical ointments containing corticosteroids along with locally acting antibiotics and vitamins.

- Stimulate regeneration of DNA by using Lioxasol® and later, when regeneration has started, biogenic drugs, such as Actovegin® and Solcoseril®.

- Stimulate blood supply in third or fourth week using Pentoxifylline® (contraindicated for patients with atherosclerotic heart disease).

- Puncture blisters if they are sterile, but do not remove them as long as they are intact.

- Stay alert for wound infection. Antibiotic therapy should be considered according to the individual patient's condition.

- Treat pain according to the individual patient's condition. Pain relief is very difficult and is the most demanding part of the therapeutic process.

- Debride areas of necrosis thoroughly but cautiously.

Treatment of Late Effects

After immediate treatment of radiation injury, an often long and painful process of healing will ensue. The most important concerns are the following:

- Pain management

- Fibrosis or late ulcers

Note : Use of medication to stimulate vascularization, inhibit infection, and reduce fibrosis may be effective. Examples include Pentoxifylline®, vitamin E, and interferon gamma. Otherwise, surgery may be required.

- Necrosis

- Plastic/reconstructive surgery

Note : Surgical treatment is common. It is most effective if performed early in the treatment process. Full-thickness graft and microsurgery techniques usually provide the best results.

- Psychological effects, such as posttraumatic stress disorder

- Possibility of increased risk of skin cancer later in life

Appendix A: Responses of the Skin to Radiation

- Acute epidermal necrosis (time of onset: < 10 days postexposure; threshold dose: ~550 Gy or 55,000 rads)— Interphase death of postmitotic keratinocytes in the upper visible layers of the epidermis (may occur with high-dose, low-energy beta irradiation)

- Acute ulceration (time of onset: < 14 days postexposure; threshold dose: ~20 Gy or 2000 rads)—Early loss of the epidermis— and to a varying degree, deeper dermal tissue—that results from the death of fibroblasts and endothelial cells in interphase

- Dermal atrophy (time of onset: > 26 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~10 Gy or 1000 rads)— Thinning of the dermal tissues associated with the contraction of the previously irradiated area

- Dermal necrosis (time of onset > 10 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~20 Gy or 2000 rads)— Necrosis of the dermal tissues as a consequence of vascular insufficiency

- Dry desquamation (time of onset: 3–6 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~8 Gy or 800 rads)— Atypical keratinization of the skin caused by the reduction in the number of clonogenic cells within the basal layer of the epidermis

- Early transient erythema (time of onset: within hours of exposure; threshold dose: ~2 Gray [Gy] or 200 rads)— Inflammation of the skin caused by activation of a proteolytic enzyme that increases the permeability of the capillaries

- Epilation (time of onset: 14–21 days; threshold dose: ~3 Gy or 300 rads)— Hair loss caused by the depletion of matrix cells in the hair follicles

- Late erythema (time of onset: 8–20 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~20 Gy or 2000 rads)— Inflammation of the skin caused by injury of blood vessels. Edema and impaired lymphatic clearance precede a measured reduction in blood flow.

- Invasive fibrosis (time of onset: months to years postexposure; threshold dose: ~20 Gy or 2000 rads)— Method of healing associated with acute ulceration, secondary ulceration, and dermal necrosis that leads to scar tissue formation

- Main erythema (time of onset: days to weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~3 Gy or 300 rads)— Inflammation of the skin caused by hyperaemia of the basal cells and subsequent epidermal hypoplasia (see photos 1 and 2)

- Moist desquamation (time of onset: 4–6 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~15 Gy or 1500 rads)— Loss of the epidermis caused by sterilization of a high proportion of clonogenic cells within the basal layer of the epidermis

- Secondary ulceration (time of onset: > 6 weeks postexposure; threshold dose: ~15 Gy or 1500 rads)— Secondary damage to the dermis as a consequence of dehydration and infection when moist desquamation is severe and protracted because of reproductive sterilization of the vast majority of the clonogenic cells in the irradiated area

- Telangiectasia (time of onset: > 52 weeks postexposure; threshold dose for moderate severity at 5 years: ~40 Gy or 4000 rads)— Atypical dilation of the superficial dermal capillaries.

Appendix B: Images

Figures 1 & 2 . Erythema: These photos display the progression of erythema in a patient involved in an x-ray diffraction accident, 9 days to 96 days postexposure. The day following the exposure (not shown), the patient displayed only mild diffuse swelling and erythema of the fingertips. On day 9, punctuate lesions resembling telangiectasias were noted in the subungal region of the right index finger, and on day 11, blisters began to appear. Desquamation continued for several weeks. The patient developed cellulitis in the right thumb approximately 2 years following exposure. The area of the right fingertip and nail continued to cause the patient great pain when even minor trauma occurred to the fingertip, and he required occasional oral narcotic analgesics to manage this pain. He continued to experience intense pain resulting from minor trauma to the affected areas for as long as 4 years postexposure.

(Photos courtesy of Gusev IA)

Figures 3 & 4. Acute ulceration. These photos show acute ulceration in a Peruvian patient who inadvertently placed a 26-Ci (0.962-TBq) irridiun-192 ( 192 Ir) source in his back pocket, 3 days and 10 days postexposure. The source remained in the patient's pocket for approximately 6.5 hours, at which time he complained to his wife about pain in his posterior right thigh. He sought medical advice and was told he probably had been bitten by an insect. In the meantime, his wife sat on the patient's pants (her case appears on the next page) while breastfeeding the couple's 1½-year-old child. The source was recovered several hours later by nuclear regulatory authorities, and the patient was transported to Lima for treatment. This patient exhibited a drastic reduction in lymphocyte count by day 3 postexposure, and a 4-by-4-cm lesion appeared on day 4. Eventually he suffered with a massive ulceration and necrosis of the site with infection, and his right leg was amputated. Grade II and III CRI was also evident on his hands, left leg, and perineum, but he survived and returned to his family.

Acute Radiation Syndrome: A Fact Sheet for Physicians

Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) (sometimes known as radiation toxicity or radiation sickness) is an acute illness caused by irradiation of the entire body (or most of the body) by a high dose of penetrating radiation in a very short period of time (usually a matter of minutes). The major cause of this syndrome is depletion of immature parenchymal stem cells in specific tissues. Examples of people who suffered from ARS are the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs, the firefighters that first responded after the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant event in 1986, and some unintentional exposures to sterilization irradiators.

The required conditions for Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) are:

- The radiation dose must be large (i.e., greater than 0.7 Gray (Gy)1, 2 or 70 rads).

- Mild symptoms may be observed with doses as low as 0.3 Gy or 30 rads.

- The dose usually must be external ( i.e., the source of radiation is outside of the patient’s body).

- Radioactive materials deposited inside the body have produced some ARS effects only in extremely rare cases.

- The radiation must be penetrating (i.e., able to reach the internal organs).

- High energy X-rays, gamma rays, and neutrons are penetrating radiations.

- The entire body (or a significant portion of it) must have received the dose3.

- Most radiation injuries are local, frequently involving the hands, and these local injuries seldom cause classical signs of ARS.

- The dose must have been delivered in a short time (usually a matter of minutes).

- Fractionated doses are often used in radiation therapy. These are large total doses delivered in small daily amounts over a period of time. Fractionated doses are less effective at inducing ARS than a single dose of the same magnitude.

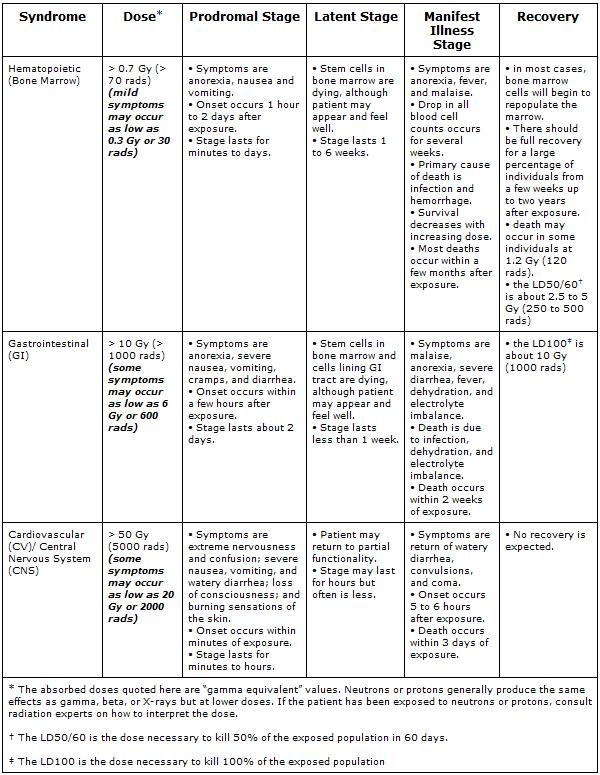

The three classic Acute Radiation Syndromes are

- Bone marrow syndrome (sometimes referred to as hematopoietic syndrome) the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose between 0.7 and 10 Gy (70 – 1000 rads) though mild symptoms may occur as low as 0.3 Gy or 30 rads4.

- The survival rate of patients with this syndrome decreases with increasing dose. The primary cause of death is the destruction of the bone marrow, resulting in infection and hemorrhage.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) syndrome: the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose greater than approximately 10 Gy (1000 rads) although some symptoms may occur as low as 6 Gy or 600 rads.

- Survival is extremely unlikely with this syndrome. Destructive and irreparable changes in the GI tract and bone marrow usually cause infection, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalance. Death usually occurs within 2 weeks.

- Cardiovascular (CV)/ Central Nervous System (CNS) syndrome: the full syndrome will usually occur with a dose greater than approximately 50 Gy (5000 rads) although some symptoms may occur as low as 20 Gy or 2000 rads.

- Death occurs within 3 days. Death likely is due to collapse of the circulatory system as well as increased pressure in the confining cranial vault as the result of increased fluid content caused by edema, vasculitis, and meningitis.

The four stages of ARS are

- Prodromal stage (N-V-D stage): The classic symptoms for this stage are nausea, vomiting, as well as anorexia and possibly diarrhea (depending on dose), which occur from minutes to days following exposure. The symptoms may last (episodically) for minutes up to several days.

- Latent stage: In this stage, the patient looks and feels generally healthy for a few hours or even up to a few weeks.

- Manifest illness stage: In this stage the symptoms depend on the specific syndrome (see Table 1) and last from hours up to several months.

- Recovery or death: Most patients who do not recover will die within several months of exposure. The recovery process lasts from several weeks up to two years.

Cutaneous Radiation Syndrome (CRS)

The concept of cutaneous radiation syndrome (CRS) was introduced in recent years to describe the complex pathological syndrome that results from acute radiation exposure to the skin.

ARS usually will be accompanied by some skin damage. It is also possible to receive a damaging dose to the skin without symptoms of ARS, especially with acute exposures to beta radiation or X-rays. Sometimes this occurs when radioactive materials contaminate a patient’s skin or clothes.

When the basal cell layer of the skin is damaged by radiation, inflammation, erythema, and dry or moist desquamation can occur. Also, hair follicles may be damaged, causing epilation. Within a few hours after irradiation, a transient and inconsistent erythema (associated with itching) can occur. Then, a latent phase may occur and last from a few days up to several weeks, when intense reddening, blistering, and ulceration of the irradiated site are visible. In most cases, healing occurs by regenerative means; however, very large skin doses can cause permanent hair loss, damaged sebaceous and sweat glands, atrophy, fibrosis, decreased or increased skin pigmentation, and ulceration or necrosis of the exposed tissue. Patient Management

Triage: If radiation exposure is suspected:

- Secure ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) and physiologic monitoring (blood pressure, blood gases, electrolyte and urine output) as appropriate.

- Treat major trauma, burns and respiratory injury if evident.

- In addition to the blood samples required to address the trauma, obtain blood samples for CBC (complete blood count), with attention to lymphocyte count, and HLA (human leukocyte antigen) typing prior to any initial transfusion and at periodic intervals following transfusion.

- Treat contamination as needed.

- If exposure occurred within 8 to 12 hours, repeat CBC, with attention to lymphocyte count, 2 or 3 more times (approximately every 2 to 3 hours) to assess lymphocyte depletion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ARS can be difficult to make because ARS causes no unique disease. Also, depending on the dose, the prodromal stage may not occur for hours or days after exposure, or the patient may already be in the latent stage by the time they receive treatment, in which case the patient may appear and feel well when first assessed.

If a patient received more than 0.05 Gy (5 rads) and three or four CBCs are taken within 8 to 12 hours of the exposure, a quick estimate of the dose can be made (see Ricks, et. al. for details). If these initial blood counts are not taken, the dose can still be estimated by using CBC results over the first few days. It would be best to have radiation dosimetrists conduct the dose assessment, if possible.

If a patient is known to have been or suspected of having been exposed to a large radiation dose, draw blood for CBC analysis with special attention to the lymphocyte count, every 2 to 3 hours during the first 8 hours after exposure (and every 4 to 6 hours for the next 2 days). Observe the patient during this time for symptoms and consult with radiation experts before ruling out ARS.

If no radiation exposure is initially suspected, you may consider ARS in the differential diagnosis if a history exists of nausea and vomiting that is unexplained by other causes. Other indications are bleeding, epilation, or white blood count (WBC) and platelet counts abnormally low a few days or weeks after unexplained nausea and vomiting. Again, consider CBC and chromosome analysis and consultation with radiation experts to confirm diagnosis.

Initial Treatment and Diagnostic Evaluation

Treat vomiting, and repeat CBC analysis, with special attention to the lymphocyte count, every 2 to 3 hours for the first 8 to 12 hours following exposure (and every 4 to 6 hours for the following 2 or 3 days). Sequential changes in absolute lymphocyte counts over time are demonstrated below in the Andrews Lymphocyte Nomogram (see Figure 1). Precisely record all clinical symptoms, particularly nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and itching, reddening or blistering of the skin. Be sure to include time of onset.

Note and record areas of erythema. If possible, take color photographs of suspected radiation skin damage. Consider tissue, blood typing, and initiating viral prophylaxis. Promptly consult with radiation, hematology, and radiotherapy experts about dosimetry, prognosis, and treatment options. Call the Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site (REAC/TS) at (865) 576-3131 (M-F, 8 am to 4:30 am EST) or (865) 576-1005 (after hours) to record the incident in the Radiation Accident Registry System.

After consultation, begin the following (as indicated):

- supportive care in a clean environment (if available, the use of a burn unit may be quite effective)

- prevention and treatment of infections

- stimulation of hematopoiesis by use of growth factors

- stem cell transfusions or platelet transfusions (if platelet count is too low)

- psychological support

- careful observation for erythema (document locations), hair loss, skin injury, mucositis, parotitis, weight loss, or fever

- confirmation of initial dose estimate using chromosome aberration cytogenetic bioassay when possible. Although resource intensive, this is the best method of dose assessment following acute exposures.

- consultation with experts in radiation accident management.

Source

References

- Berger ME, O’Hare FM Jr, Ricks RC, editors. The Medical Basis for Radiation Accident Preparedness: The Clinical Care of Victims. REAC/TS Conference on the Medical Basis for Radiation Accident Preparedness. New York : Parthenon Publishing; 2002.

- Gusev IA , Guskova AK , Mettler FA Jr, editors. Medical Management of Radiation Accidents, 2 nd ed., New York : CRC Press, Inc.; 2001.

- Jarrett DG. Medical Management of Radiological Casualties Handbook, 1 st ed. Bethesda , Maryland : Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI); 1999.

- LaTorre TE. Primer of Medical Radiobiology, 2 nd ed. Chicago : Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1989.

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP). Management of Terrorist Events Involving Radioactive Material, NCRP Report No. 138. Bethesda , Maryland : NCRP; 2001.

- Prasad KN. Handbook of Radiobiology, 2 nd ed. New York : CRC Press, Inc.; 1995.