|

|

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) |

| Line 5: |

Line 5: |

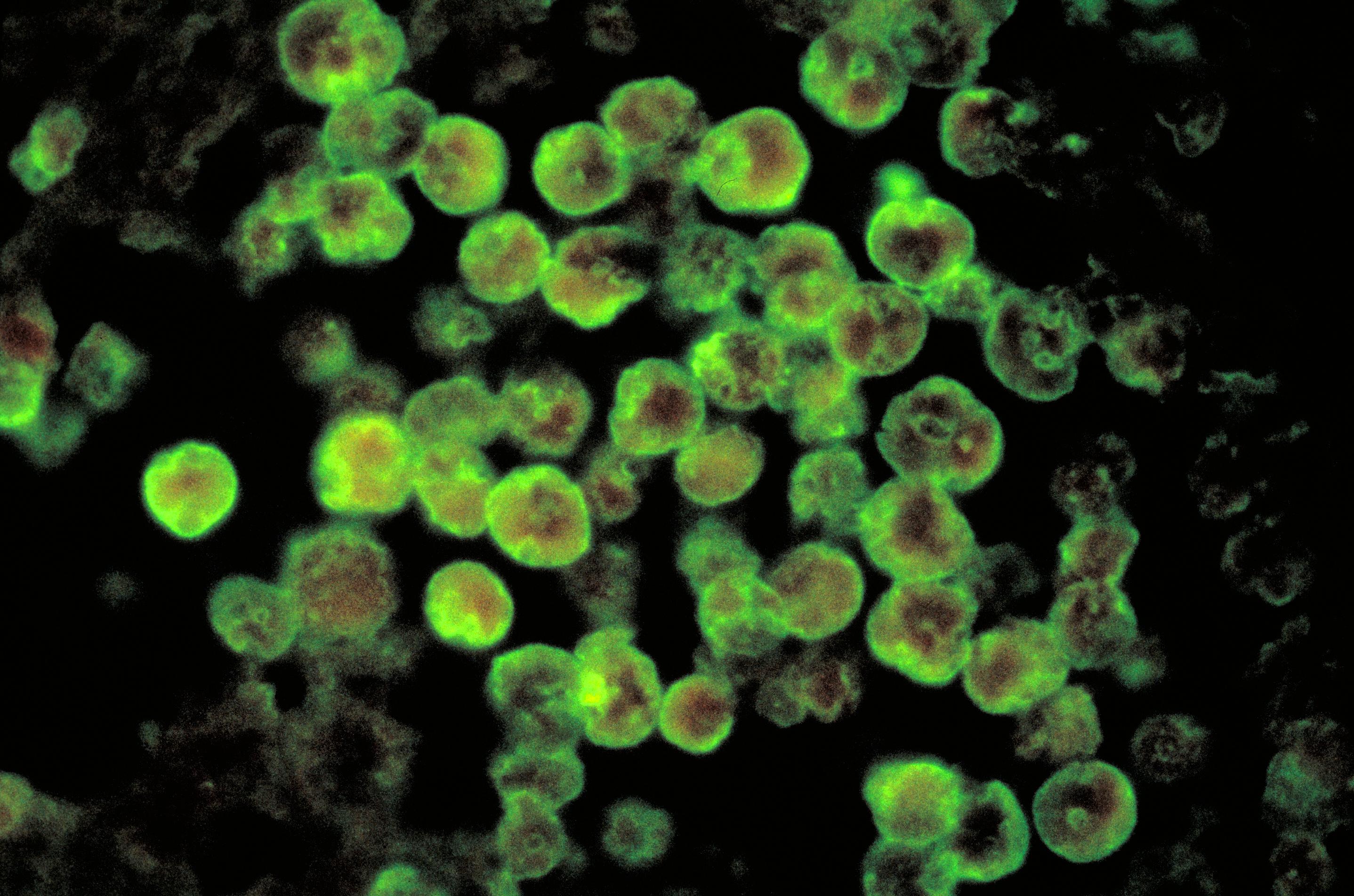

| | Caption = Histopathology of amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Direct fluorescent antibody stain. (CDC) | | | Caption = Histopathology of amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Direct fluorescent antibody stain. (CDC) |

| }} | | }} |

| {{SI}} | | {{About1|Naegleria fowleri}} |

| | '''For patient information, click [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (patient information)|here]]''' |

| | {{Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis}} |

| {{CMG}} | | {{CMG}} |

| ==Overview==

| |

| '''Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis''' ('''PAM''', or '''PAME''') is a disease of the [[central nervous system]] caused by infection from ''[[Naegleria fowleri]]''.<ref name="pmid11425704">{{cite journal |author=Cabanes PA, Wallet F, Pringuez E, Pernin P |title=Assessing the risk of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis from swimming in the presence of environmental Naegleria fowleri |journal=Appl. Environ. Microbiol. |volume=67 |issue=7 |pages=2927–31 |year=2001 |month=July |pmid=11425704 |pmc=92963 |doi=10.1128/AEM.67.7.2927-2931.2001 |url=http://aem.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11425704}}</ref><ref name="Sarica2009">{{cite pmid|19621290}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Presentation==

| | {{SK}} PAM; PAME; ''Naegleria fowleri'' infection; ''N. fowleri'' infection; primary amebic meningoencephalitis |

| ''Naegleria fowleri'' propagates in warm, stagnant bodies of [[freshwater]] (typically during the summer months), and enters the central nervous system after [[Insufflation (medicine)|insufflation]] of infected water by attaching itself to the [[olfactory nerve]].<ref name="pmid18509301">{{cite journal |title=Primary amebic meningoencephalitis—Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007 |journal=MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. |volume=57 |issue=21 |pages=573–7 |year=2008 |month=May |pmid=18509301 |url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5721a1.htm |author1= Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)}}</ref> It then migrates through the [[cribiform plate]] and into the [[olfactory bulbs]] of the [[forebrain]],<ref name="pmid18374627">{{cite journal |author=Cervantes-Sandoval I, Serrano-Luna Jde J, García-Latorre E, Tsutsumi V, Shibayama M |title=Characterization of brain inflammation during primary amoebic meningoencephalitis |journal=Parasitol. Int. |volume=57 |issue=3 |pages=307–13 |year=2008 |month=September |pmid=18374627 |doi=10.1016/j.parint.2008.01.006 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1383-5769(08)00007-X}}</ref> where it multiplies itself greatly by feeding on nerve tissue. During this stage, occurring approximately 3–7 days post-infection, the typical symptoms are [[parosmia]], rapidly progressing to [[anosmia]] (with resultant [[ageusia]]) as the nerve cells of the olfactory bulbs are consumed and replaced with [[necrotic]] lesions. | |

|

| |

|

| After the organisms have multiplied and largely consumed the olfactory bulbs, the infection rapidly spreads through the [[mitral cell]] [[axons]] to the rest of the [[cerebrum]], resulting in onset of frank [[encephalitis|encephalitic]] symptoms, including [[cephalgia]] (headache), [[nausea]], and [[Rigidity (neurology)|rigidity]] of the neck muscles, progressing to vomiting, [[delirium]], [[seizures]], and eventually irreversible coma. Death usually occurs within 14 days of exposure as a result of [[respiratory failure]] when the infection spreads to the [[brain stem]], destroying the autonomic nerve cells of the [[medulla oblongata]].

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis overview|Overview]]== |

|

| |

|

| The disease is both exceptionally rare and highly lethal: there had been fewer than 200 confirmed cases in recorded medical history as of 2004,<ref name="pmid15208515">{{cite journal |author=Wiwanitkit V |title=Review of clinical presentations in Thai patients with primary amoebic meningoencephalitis |journal=MedGenMed |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=2 |year=2004 |pmid=15208515 |pmc=1140726 |url=http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/468088}}</ref> 300 cases as of 2008,<ref name="pmid18820207">{{cite journal |author=Caruzo G, Cardozo J |title=Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: a new case from Venezuela |journal=Trop Doct |volume=38 |issue=4 |pages=256–7 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18820207 |doi=10.1258/td.2008.070426 |url=http://td.rsmjournals.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18820207}}</ref> with an in-hospital [[case fatality rate]] of ~97% (3% patient [[survival rate]]).

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis historical perspective|Historical Perspective]]== |

| <ref>{{cite web|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/996227-overview|title=Amebic Meningoencephalitis|accessdate=16 July 2010}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| The high [[mortality rate]] of this disease is largely blamed on the unusually non-suggestive [[symptom]]ology of the early-stage disease compounded by the necessity of [[microbial culture]] of the [[cerebrospinal fluid]] to effect a positive [[diagnosis]]. The parasite also demonstrates a particularly rapid late-stage propagation through the nerves of the [[olfactory system]] to many parts of the brain simultaneously (including the vulnerable [[Medulla oblongata|medulla]]).

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis pathophysiology|Pathophysiology]]== |

|

| |

|

| For those reasons, it has been suggested that physicians should give an array of antimicrobial drugs, including the drugs used to treat amoebic encephalitis, before the disease is actually confirmed in order to increase the number of survivors. However, administering several of those drugs at once (or even some of them known to treat the condition) is often very dangerous and unpleasant for the patient.

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis causes|Causes]]== |

|

| |

|

| ==Cause== | | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis differential diagnosis|Differentiating Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis from other Diseases]]== |

| ''Naegleria fowleri'' is commonly referred to as an amoeba but is actually a unicellular parasite that is ubiquitous in soils and warm waters. Infection typically occurs during the summer months and patients typically have a history of exposure to a natural body of water. The organism specifically prefers temperatures above 32 °C, as might be found in a tropical climate{{Citation needed|date=January 2009}} or in water heated by geothermal activity.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ew.govt.nz/Environmental-information/Natural-hazards/Geothermal-activity/|title=Geothermal activity|accessdate=9 January 2008}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> The organism is extremely sensitive to chlorine (<0.5 ppm). Exposure to the organism is extremely common due to its wide distribution in nature, but thus far lacks the ability to infect the body through any method other than direct contact with the olfactory nerve, which is exposed only at the extreme vertical terminus of the [[paranasal sinuses]]; the contaminated water must be deeply insufflated into the [[paranasal sinuses|sinus cavities]] for transmission to occur.

| |

|

| |

|

| Michael Beach, a recreational waterborne illness specialist for the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]], stated in remarks to the Associated Press that the wearing of nose-clips to prevent insufflation of contaminated water would be an effective protection against contracting PAM, noting that "You'd have to have water going way up in your nose to begin with".<ref>''"6 die from brain-eating amoeba in lakes"'', Chris Kahn/Associated Press, 9/28/07</ref>

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== |

|

| |

|

| ==Occurrence== | | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis risk factors|Risk Factors]]== |

|

| |

|

| This form of nervous system infection by amoeba was first documented in Australia in 1965.<ref name="pmid5825411">{{cite journal |author=Fowler M, Carter RF |title=Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acanthamoeba sp.: a preliminary report |journal=Br Med J |volume=2 |issue=5464 |pages=740–2 |year=1965 |month=September |pmid=5825411 |url= |pmc=1846173}}</ref><ref name="pmid5354833">{{cite journal |author=Symmers WC |title=Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Britain |journal=Br Med J |volume=4 |issue=5681 |pages=449–54 |year=1969 |month=November |pmid=5354833 |pmc=1630535 |doi= 10.1136/bmj.4.5681.449|url=}}</ref> In 1966, four cases were reported in the USA. By 1968 the causative organism, previously thought to be a species of ''Acanthamoeba'' or ''Hartmanella'', was identified as ''Naegleria''. This same year, occurrence of 16 cases over period of two years (1963–1965) was reported in [[Ústí nad Labem]].<ref>{{cite journal | author=Červa L. | coauthors=K. Novák | title=Ameobic meningoencephalitis: sixteen fatalities| journal=Science| year=160 | date = 5 April 1968 | pages=92 | doi=10.1126/science.160.3823.92 | pmid=5642317 | volume=160 | issue=3823 }}</ref> In 1970, the species of amoeba was named ''N. fowleri''.<ref>{{cite book

| | ==[[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis natural history, complications and prognosis|Natural History, Complications and Prognosis]]== |

| |last=Gutierrez|first=Yezid

| |

| |title=Diagnostic Pathology of Parasitic Infections with Clinical Correlations

| |

| |url=

| |

| |edition=2

| |

| |date=15

| |

| |year=2000

| |

| |month=January

| |

| |publisher=Oxford University Press

| |

| |location=USA

| |

| |isbn=0-19-512143-0

| |

| |oclc=

| |

| |id=

| |

| |pages=114–115

| |

| |chapter=Chapter 6: Free Living Amebae

| |

| |chapterurl=

| |

| |quote=

| |

| |ref=http://books.google.com.au/books?id=oKSEhVMVrJ4C&pg=PA115&lpg=PA115&dq=meningitis+australia+outbreak+amebic+OR+amoebic+amebic+OR+amoebic&source=web&ots=Wh22FBPzKB&sig=wJHcjtt5AXP_rd9O0Z5y8EqRiuo&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result

| |

| }}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| In 2010, a 7-year-old girl in [[Stillwater, Minnesota]] died of the disease.<ref name="minn">{{cite web|url=http://www.startribune.com/local/east/101599778.html?elr=KArksLckD8EQDUoaEyqyP4O:DW3ckUiD3aPc:_Yyc:aUac8HEaDiaMDCinchO7DU|title=Stillwater girl dies of very rare form of meningitis|accessdate=26 August 2010|publisher=[[Minneapolis Star Tribune]]}}</ref>

| | ==Diagnosis== |

| | | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis history and symptoms|History and Symptoms]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis physical examination|Physical Examination]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis laboratory findings|Laboratory Findings]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis other imaging findings|Other Imaging Findings]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis other diagnostic studies|Other Diagnostic Studies]] |

| In August 2010, 7-year-old Kyle Lewis died after contracting the protist from swimming in Lake Granbury and warm water near Glen Rose, Texas. Texas authorities say this is the tenth case since 2000.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pegasusnews.com/news/2010/aug/31/tarrant-county-resident-dies-amoeba-infection/ |title=Tarrant County resident dies from amoeba infection |publisher=Pegasus News |date=August 31, 2010 |accessdate=2011-08-17}}</ref> http://www.KyleCares.org

| |

| | |

| In August 2011, a 16-year-old girl in [[Mims, Florida]] died after swimming in the [[St. Johns River|St. John's River]] a week earlier. Doctors found ''N. fowleri'' in her cerebral spinal fluid.<ref name="vynbos">{{cite web|url=http://www.nydailynews.com/news/2011/08/14/2011-08-14_florida_teen_courtney_nash_dies_from_rare_brain_parasite_after_swimming_in_river.html|title=Florida teen, Courtney Nash, dies from rare brain parasite|accessdate=15 August 2011|publisher=[[NY Daily News]]}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| As of December 2011, two individuals in Louisiana died after inhaling infected tap water while using a [[neti pot]].<ref>{{cite web

| |

| |last = Stobbe|first = Mike

| |

| |title = Two die of rare brain infection from amoeba in water in neti pot

| |

| |url = http://vitals.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2011/12/16/9503070-neti-pots-linked-to-brain-eating-amoeba-deaths

| |

| |accessdate =19 December 2011}}

| |

| </ref>

| |

| <ref>{{cite web

| |

| |agency=Associated Press | publisher=Yahoo! | |

| |title = Neti Pot Deaths Linked to Brain-Eating Amoeba in Tap Water

| |

| |url = http://health.yahoo.net/articles/flu/neti-pot-deaths-linked-brain-eating-amoeba-tap-water

| |

| |accessdate =19 December 2011}}

| |

| </ref>

| |

| | |

| In July 2012, an 8 year old boy from [[Sumter, SC]] died after swimming in [[Lake Marion (South Carolina)|Lake Marion]].<ref>{{cite web

| |

| |agency=The State | |

| |title=Sumter boy dies of rare brain infection

| |

| |url = http://www.thestate.com/2012/07/19/2360073/sumter-boy-dies-of-rare-brain.html

| |

| |accessdate 19 July 2012}}

| |

| </ref> In southern part of [[Pakistan]], 8 people died within a week of July 2012.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thenewstribe.com/2012/07/19/naegleria-spread-in-karachi-causes-symptoms-and-prevention/| title= 8 dies in Karachi due to Naegleria| accessdate = 2012-7-19}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| In August 2012, Jack Ariola Erenberg, a 9 year old boy from Stillwater, Minnesota, died after swimming in Lily Lake near his home. <ref>http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2186295/Jack-Ariola-9-killed-contracting-brain-eating-amoeba-Lily-Lake-Minnesota.html</ref>

| |

| | |

| August 7, 2012, Waylon Abel, 30, of Loogootee IN died after swimming in West Boggs Lake near his home. <ref>http://washtimesherald.com/local/x620788801/Beach-closed-Autopsy-confirms-rare-parasite</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Treatment== | | ==Treatment== |

| | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis medical therapy|Medical Therapy]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis surgery|Surgery]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis primary prevention|Primary Prevention]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis cost-effectiveness of therapy|Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy]] | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis future or investigational therapies|Future or Investigational Therapies]] |

|

| |

|

| The current standard treatment is prompt [[intravenous]] administration of [[heroic measure|heroic]] doses of [[Amphotericin B]], a systemic [[Antifungal medication|antifungal]] that is one of the few effective treatments for systemic infections of [[protozoan]] [[parasitic diseases]] (such as [[leishmaniasis]] and [[toxoplasmosis]]).

| | ==Case Studies== |

| | | [[Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis case study one|Case #1]] |

| The success rate in treating PAM is usually quite poor, since by the time of definitive diagnosis most patients have already manifested signs of terminal cerebral [[necrosis]]. Even if definitive diagnosis is effected early enough to allow for a course of medication, Amphotericin B also causes significant and permanent [[nephrotoxicity]] in the doses necessary to quickly halt the progress of the amoebae through the brain.

| |

| | |

| [[Rifampicin]] has also been used with amphotericin B in successful treatment.<ref name="pmid2056258">{{cite journal |author=Poungvarin N, Jariya P |title=The fifth nonlethal case of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis |journal=J Med Assoc Thai |volume=74 |issue=2 |pages=112–5 |year=1991 |month=February |pmid=2056258 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid12577098">{{cite journal |author=Jain R, Prabhakar S, Modi M, Bhatia R, Sehgal R |title=Naegleria meningitis: a rare survival |journal=Neurol India |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=470–2 |year=2002 |month=December |pmid=12577098 |url=http://www.neurologyindia.com/article.asp?issn=0028-3886;year=2002;volume=50;issue=4;spage=470;epage=2;aulast=Jain}}</ref><ref name="pmid15900627">{{cite journal |author=Vargas-Zepeda J, Gómez-Alcalá AV, Vásquez-Morales JA, Licea-Amaya L, De Jonckheere JF, Lares-Villa F |title=Successful treatment of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis by using intravenous amphotericin B, fluconazole and rifampicin |journal=Arch. Med. Res. |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=83–6 |year=2005 |pmid=15900627 |doi= 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.11.003|url=}}</ref> However, there is some evidence that it does not effectively inhibit Naegleria growth.<ref name="urlProceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science">{{cite web |url=http://digital.library.okstate.edu/OAS/oas_htm_files/v77/p133_136nf.html |title=Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science |accessdate=2 January 2009}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Two cases of similar amoebic infections (caused by ''Balamuthia mandrillaris'') were successfully treated for amoebic encephalitis and recovered, including a 5-year-old girl and a 64-year-old man.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Deetz TR, Sawyer MH, Billman G, Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS|title=Successful treatment of Balamuthia amoebic encephalitis: presentation of 2 cases|journal=Clin Infect Dis|volume=37|issue=10|pages=1304–12|year=200|pmid=14583863|url= |doi=10.1086/379020}}</ref> The successful use of a combination regimen that includes one amebicidal drug ([[miltefosine]]) along with two amebistatic drugs capable of crossing the brain-blood barrier ([[fluconazole]] and [[albendazole]]) provides hope for attaining clinical cure for an otherwise lethal condition.

| |

| | |

| There is preclinical evidence that the relatively safe, inexpensive, and widely available [[phenothiazine]] [[antipsychotic]] [[chlorpromazine]] is a highly efficacious amebicide against ''N. fowleri'', with laboratory animal survival rates nearly double those receiving treatment with amphotericin B.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Kim|first=JH|coauthors=Jung, SY, Lee, YJ, Song, KJ, Kwon, D, Kim, K, Park, S, Im, KI, Shin, HJ|title=Effect of therapeutic chemical agents in vitro and on experimental meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri.|journal=Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy|date=November 2008|year=2008|month=November|volume=52|issue=11|pages=4010–6|doi=10.1128/AAC.00197-08|pmid=18765686|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2573150/?tool=pubmed|accessdate=22 April 2012|pmc=2573150}}</ref> The mechanism of action is possibly the inhibition of the ''nfa1'' and ''Mp2CL5'' genes, found only in pathogenic strains of ''N. fowleri'', which are involved in amoebic [[phagocytosis]] and regulation of cellular growth, respectively.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tiewcharoen|first=Supathra|title=Activity of chlorpromazine on nfa1 and Mp2CL5 genes of Naegleria fowleri trophozoites|journal=Health|date=1 January 2011|volume=03|issue=03|pages=166–171|doi=10.4236/health.2011.33032|url=http://www.scirp.org/Journal/PaperInformation.aspx?paperID=4314|accessdate=22 April 2012}}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| ==See also== | | ==Related Chapters== |

| * [[Free-living amebic infection]] | | *[[Free-living amebic infection]] |

| * [[Meningoencephalitis]] | | *[[Meningoencephalitis]] |

| * [[Waterborne diseases]] | | *[[Waterborne diseases]] |

| * [[Acanthamoeba]] | | *[[Acanthamoeba]] |

|

| |

|

| ==References==

| | ==External Links== |

| {{reflist|2}}

| | *[http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/ Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis] – [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] |

| | |

| ==External links== | |

| *[http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/ ''Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis''] – [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] | |

| * http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/primary_amebic_meningoencephalitis/ | | * http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/idcu/disease/primary_amebic_meningoencephalitis/ |

| * http://health.yahoo.net/articles/flu/neti-pot-deaths-linked-brain-eating-amoeba-tap-water

| |

|

| |

|

| {{Excavata diseases}}

| |

| {{CNS diseases of the nervous system}} | | {{CNS diseases of the nervous system}} |

|

| |

|

| [[Category:Protozoal diseases]]

| |

| [[Category:Encephalitis]]

| |

| [[Category:Inflammations]] | | [[Category:Inflammations]] |

| [[Category:Meningitis]] | | [[Category:Meningitis]] |

| [[Category:Infectious disease]]

| |

| [[Category:Neurological Disease]]

| |

|

| |

|

| [[ca:Meningoencefalitis amèbica primària]] | | [[Category:Neurology]] |

| [[fr:Méningo-encéphalite amibienne primitive]] | | [[Category:Disease]] |

| [[hr:Primarni amebni meningoencefalitis]]

| | |

| [[it:Meningoencefalite amebica primaria]]

| | {{WH}} |

| [[pl:Neglerioza]]

| | {{WS}} |