Pneumothorax: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kashish Goel (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

MeshID = D011030 | | MeshID = D011030 | | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{ | '''For patient information click [[{{PAGENAME}} (patient information)|here]]''' | ||

{{Pneumothorax}} | |||

{{CMG}} | |||

==[[Pneumothorax overview|Overview]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax historical perspective|Historical perspective]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax pathophysiology|Pathophysiology]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax epidemiology and demographics|Epidemiology and Demographics]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax risk factors|Risk factors]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax screening|Screening]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax causes|Causes]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax differential diagnosis|Differentiating Pneumothorax from other Disorders]]== | |||

==[[Pneumothorax natural history|Natural History, Complications & Prognosis]]== | |||

==Diagnosis== | |||

[[Pneumothorax history and symptoms|History & Symptoms]] | [[Pneumothorax physical examination|Physical examination]] | [[Pneumothorax chest x ray|Chest X ray]] |[[Pneumothorax laboratory tests|Laboratory Tests]] | [[Pneumothorax electrocardiogram | Electrocardiogram]] | [[Pneumothorax MRI|MRI]] | [[Pneumothorax CT|CT]] |[[Pneumothorax echocardiography|Echocardiography]] | [[Pertussis other imaging findings|Other Imaging Findings]] | [[Pneumothorax other diagnostic studies|Other Diagnostic Studies]] | |||

==Treatment== | |||

'''Medical:''' [[Pneumothorax medical therapy|Medical Therapy]] | |||

'''Surgical:''' [[Pneumothorax surgery|Surgery]] | |||

[[Pneumothorax primary prevention|Primary Prevention]] | [[Pneumothorax secondary prevention|Secondary Prevention]] | [[Pneumothorax cost-effectiveness of therapy|Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy]] | [[Pneumothorax future or investigational therapies|Future or Investigational Therapies]] | |||

==References== | |||

{{Reflist|2}} | |||

[[Category:Chest trauma]] | |||

[[Category:Diseases involving the fasciae]] | |||

[[Category:Pulmonology]] | |||

[[Category:Emergency medicine]] | |||

{{WH}} | |||

{{WS}} | |||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| Line 183: | Line 223: | ||

Prior to the advent of anti tuberculous medications, iatrogenic pneumothoraces were intentionally given to tuberculosis patients in an effort to collapse a lobe, or entire lung around a cavitating lesion. This was known as 'resting the lung' . | Prior to the advent of anti tuberculous medications, iatrogenic pneumothoraces were intentionally given to tuberculosis patients in an effort to collapse a lobe, or entire lung around a cavitating lesion. This was known as 'resting the lung' . | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 204: | Line 241: | ||

* Sucking chest wound: | * Sucking chest wound: | ||

**[http://www.brooksidepress.org/Products/OperationalMedicine/DATA/operationalmed/Procedures/TreataSuckingChestWound.htm Brookside Press / US Army - Treat a Sucking Chest Wound] | **[http://www.brooksidepress.org/Products/OperationalMedicine/DATA/operationalmed/Procedures/TreataSuckingChestWound.htm Brookside Press / US Army - Treat a Sucking Chest Wound] | ||

Revision as of 14:40, 22 September 2011

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox For patient information click here

|

Pneumothorax Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Pneumothorax On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Pneumothorax |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Historical perspective

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology and Demographics

Risk factors

Screening

Causes

Differentiating Pneumothorax from other Disorders

Natural History, Complications & Prognosis

Diagnosis

History & Symptoms | Physical examination | Chest X ray |Laboratory Tests | Electrocardiogram | MRI | CT |Echocardiography | Other Imaging Findings | Other Diagnostic Studies

Treatment

Medical: Medical Therapy

Surgical: Surgery

Primary Prevention | Secondary Prevention | Cost-Effectiveness of Therapy | Future or Investigational Therapies

References

Overview

In medicine (pulmonology), a pneumothorax, or collapsed lung, is a potential medical emergency caused by accumulation of air or gas in the pleural cavity, occurring as a result of disease or injury.[1]

Epidemiology and Demographics

Spontaneous pneumothoraces are reported in young people with a tall stature. As men are generally taller than women, there is a preponderance among males. The reason for this association, while unknown, is hypothesized to be the presence of subtle abnormalities in connective tissue. Some spontaneous pneumothoraces however, are results of "blebs", blister like structures on the surface of the lung, that rupture allowing the escape of air into the pleural cavity.

Pneumothorax can also occur as part of medical procedures, such as the insertion of a central venous catheter (an intravenous catheter) in the subclavian vein or jugular vein. While rare, it is considered a serious complication and needs immediate treatment. Other causes include mechanical ventilation, emphysema and rarely other lung diseases (pneumonia).

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The lungs are located inside the chest cavity, which is a hollow space. Air is drawn into the lungs by the diaphragm (a powerful abdominal muscle). The pleural cavity is the region between the chest wall and the lungs. If air enters the pleural cavity, either from the outside (open pneumothorax) or from the lung (closed pneumothorax), the lung collapses and it becomes mechanically impossible for the injured person to breathe, even with an open airway. If a piece of tissue forms a one-way valve that allows air to enter the pleural cavity from the lung but not to escape, overpressure can build up with every breath; this is known as tension pneumothorax. It may lead to severe shortness of breath as well as circulatory collapse, both life-threatening conditions. This condition requires urgent intervention.

Natural History

If left untreated, hypoxia may lead to loss of consciousness and coma. In addition, shifting of the mediastinum away from the site of the injury can obstruct the superior and inferior vena cava resulting in reduced cardiac preload and decreased cardiac output. Untreated, a severe pneumothorax can lead to death within several minutes.

Classification Scheme

Pneumothoraces are divided into tension and non-tension pneumathoraces.

- A tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency as air accumulates in the pleural space with each breath. The increase in intrathoracic pressure results in massive shifts of the mediastinum away from the affected lung compressing intrathoracic vessels.

- A non-tension pneumothorax by contrast is a less severe pathology because there is no ongoing accumulation of air and hence no increasing pressure on the organs within the chest.

The accumulation of blood in the thoracic cavity (hemothorax) exacerbates the problem, creating a pneumohemothorax.

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

Sudden shortness of breath, dry coughs, cyanosis (turning blue) and pain felt in the chest, back and/or arms are the main symptoms. In penetrating chest wounds, the sound of air flowing through the puncture hole may indicate pneumothorax, hence the term "sucking" chest wound. The flopping sound of the punctured lung is also occasionally heard.

Physical Examination

Neck

Tracheal deviation may be present.

Lungs

The absence of audible breath sounds through a stethoscope can indicate that the lung is not unfolded in the pleural cavity. This accompanied by hyperresonance (higher pitched sounds than normal) to percussion of the chest wall is suggestive of the diagnosis. If the signs and symptoms are doubtful, an X-ray of the chest can be performed, but in severe hypoxia, emergency treatment has to be administered first.

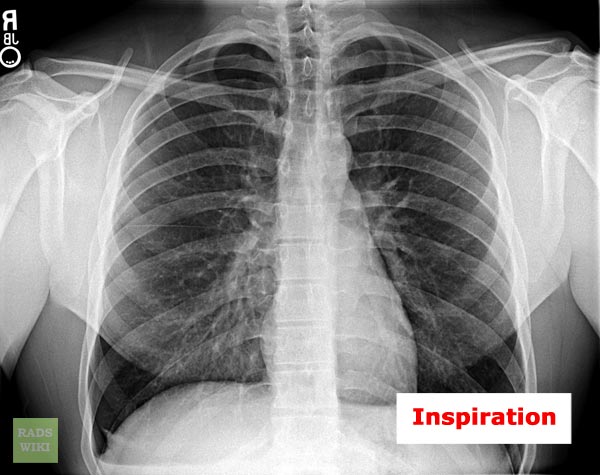

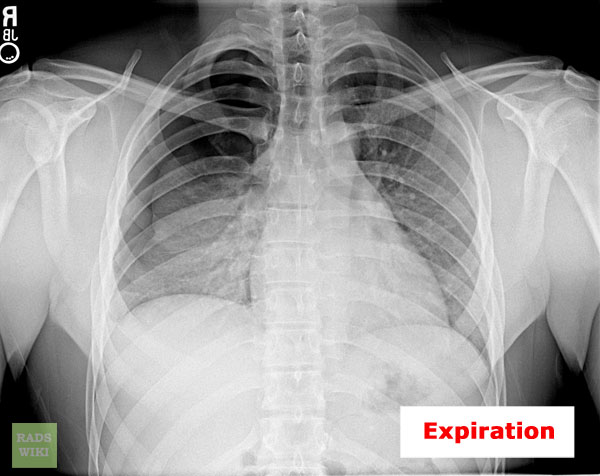

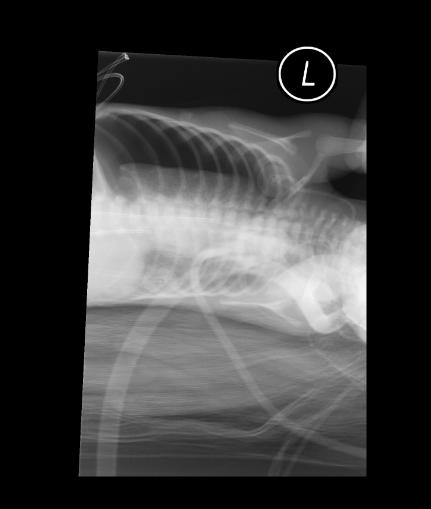

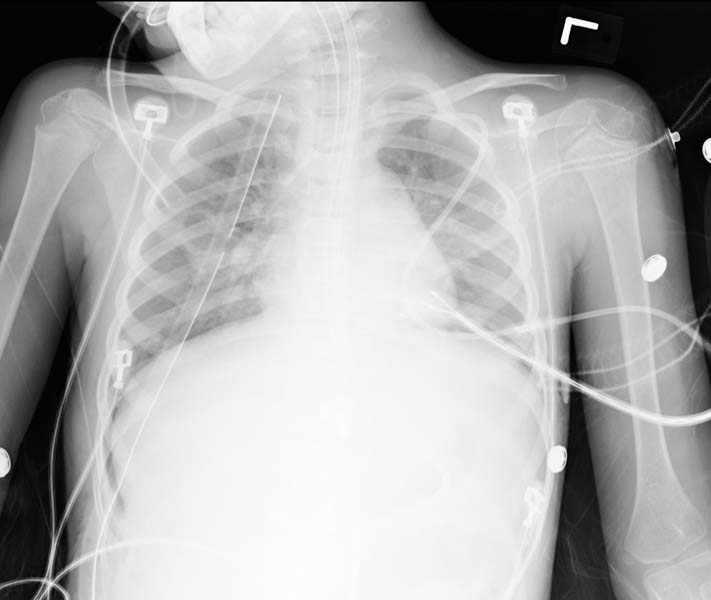

Chest X Ray

In a supine chest X-ray the deep sulcus sign is diagnostic[2], which is characterized by a low lateral costophrenic angle on the affected side.[3] In layman's terms, the place where rib and diaphragm meet appears lower on an X-ray with a deep sulcus sign and suggests the diagnosis of pneumothorax.

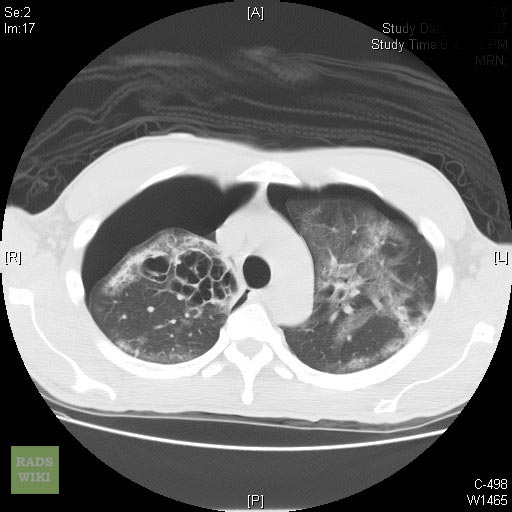

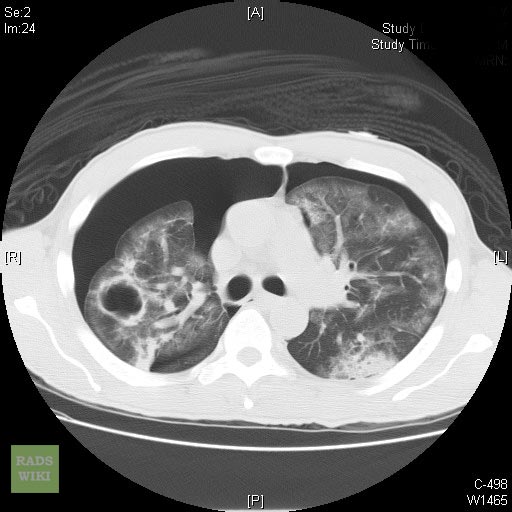

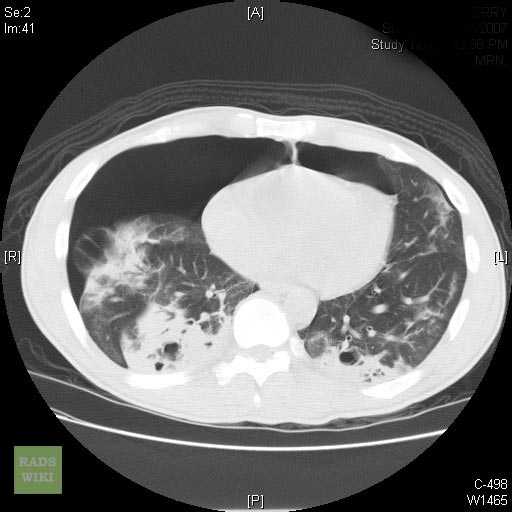

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted

Chest CT

-

Left-sided pneumothorax (on the right side of the image) on CT scan of the chest. A chest tube is in place--side of chest, the lumen (black) can be seen adjacent to the pleural cavity (black) and ribs (white). The heart can be seen in the centre.

Complete Differential Diagnosis of Underlying Causes of Pneumothorax

Causes

- Acupuncture

- Bacterial pneumonia with abscess

- Barotrauma

- Blunt trauma

- Bronchial asthma

- Cancer

- Catamenial pneumothorax (due to endometriosis in the chest cavity)

- Central bronchial carcinoma

- Coccidiomycosis

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Emphysema

- Eosinophilic Granuloma

- Hydatid lung disease

- Lung emphysema

- Marfan's Syndrome

- Mechanical ventilation

- Medastinal emphysema

- Paragonimiasis

- Positive end expiratory pressure or PEEP

- Pneumoconiosis

- Penetrating trauma

- Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Primary spontaneous pneumothorax

- Pulmonary lymphangiomatoid granulomatosis

- Pulmonary hemosiderosis

- Rheumatoid lung disease

- Rupture of cysts

- Sarcoidosis

- Spontaneously (most commonly in tall slim young males and in Marfan syndrome)

- Sudden chest compression

- Tuberculosis

Differential Diagnosis of Conditions that Pneumothorax must be Distinguished From

- Acute Myocardial Infarction: presents with shortness of breath and chest pain, though MI chest pain is characteristically crushing, central and radiating to the jaw, left arm or stomach. While not a lung condition, patients having an MI often happen to also have lung disease.

- Emphysema: here, delicate functional lung tissue is lost and replaced with air spaces, giving shortness of breath, and decreased air entry and increased resonance on examination. However, it is usually a chronic condition, and signs are diffuse (not localised as in pneumothorax).

A careful history, physical examination and a chest x-ray will allow the conditions to be differentiated.

Treatment

Emergency Care

Chest wound

Penetrating wounds require immediate coverage with an occlusive dressing, field dressing, or pressure bandage made air-tight with petroleum jelly or clean plastic sheeting. The sterile inside of plastic bandage packaging is good for this purpose; however any airtight material, even the cellophane of a cigarette pack, can be used. A small opening, known as a flutter valve, needs to be left open, so the air can escape while the lung reinflates.

Any patient with a penetrating chest wound must be closely watched at all times and may develop a tension pneumothorax or other immediately life-threatening respiratory emergency at any moment. They cannot be left alone.

Blast injury or tension

If the air in the pleural cavity is due to a tear in the lung tissue (in the case of a blast injury or tension pneumothorax), it needs to be released. A thin needle can be used for this purpose, to relieve the pressure and allow the lung to reinflate.

Pre-hospital care

Many paramedics can perform needle thoracocentesis to relieve intrathoracic pressure. Intubation may be required, even of a conscious patient, if the situation deteriorates. Advanced medical care and immediate evacuation are strongly indicated.

An untreated pneumothorax is an absolute contraindication of evacuation or transportation by flight.

Clinical treatment

Small pneumothoraces often are managed with no treatment other than repeat observation via Chest X-rays, but most patients admitted will have oxygen administered since this has been shown to speed resolution of the pneumothorax. [4]

Pneumothoraces which are too small to require tube thoracostomy and too large to leave untreated, have been aspirated with a needle to remove the pressure, although this technique is usually reserved for tension pneumothoraces

Larger pneumothoraces may require tube thoracostomy, also known as chest tube placement. If a thorough anesthetizing of the parietal pleura and the intercostal muscles is performed, the only major pain experienced should be either the injury that caused the pneumothorax or the re-expanding of the lung. Proper anesthetizing will come about after the needle has been inserted into the chest cavity and a negative pressure is created in the syringe. While air bubbles rise into the syringe, the needle should be pulled out of the cavity until the bubbles cease. The tip of the syringe that contains the anesthetic is now in the intercostal muscles. A proper and sizable injection should ensue. This will allow the patient to be fairly comfortable despite a hemostat or finger being inserted into the chest cavity. A tube is then inserted into the chest wall outside the lung and air is extracted using a simple one way valve or vacuum and a water valve device, depending on severity. This allows the lung to re-expand within the chest cavity. This re-expansion usually lasts for approximately 15-30 seconds depending on the size of the pneumothorax and feels as if your breath has been taken away. This response is normal and should pass fairly quickly. The pneumothorax is followed up with repeated X-rays. If the air pocket has become small enough, the vacuum drain can be clamped temporarily or removed. If during the time that the tube is still in the chest the lung manages to not contiue to collapse once suction is turned off, but will diminish if actually clamped off, a heimlich valve may be used. This flutter valve allows air and fluid in the pleural cavity to escape the pleura into a drainage bag while not letting any air or fluid back in. This method was developed by the military in order to get soldiers with lung injuries stable and out of the battle field faster. It is a rarely used medical device in treatment in patients these days, but will be used in order to allow the patient to leave the hospital.

In the situation that the chest tube does not seem to be helping the healing of the lung or if CAT scans show the presence of "blebs" on the surface of the lung orthoscopic surgery may be done in order to staple the lung closed. Two small incisions are made in the back, one for a small camera and one for the tool used to seal the lung. When finished the wound is covered with a steri-strip and bandaged up.

In case of penetrating wounds, these require attention, but generally only after the airway has been secured and a chest drain inserted. Supportive therapy may include mechanical ventilation.

Recurrent pneumothorax may require further corrective and/or preventive measures such as pleurodesis. If the pneumothorax is the result of bullae, then bullectomy (the removal or stapling of bullae or other faults in the lung) is preferred. Chemical pleurodesis is the injection of a chemical irritant that triggers an inflammatory reaction, leading to adhesion of the lung to the parietal pleura. Substances used for pleurodesis include talc, blood]], tetracycline and bleomycin. Mechanical pleurodesis does not use chemicals. The surgeon "roughs" up the inside chest wall ("parietal pleura") so the lung attaches to the wall with scar tissue. This can also include a "parietal" pleurectomy, which is the removal of the "parietal" pleura; "parietal" pleura is the serous membrane lining the inner surface of the thoracic cage and facing the "visceral" pleura, which lies all over the lung surface. Both operations can be performed using keyhole surgery to minimise discomfort to the patient.

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Spontaneous Pneumothorax can be classified as primary spontaneous pneumothorax and secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. In primary spontaneous pneumothorax, it is usually characterized by a rupture of a bleb in the lung while secondary spontaneous pneumothorax mostly occurs due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax may occur without either trauma to the chest or any kind of blast injury. This type of pneumothorax is caused when a bleb (an imperfection in the lining of the lung) bursts causing the lung to deflate. If a patient suffers two or more instances of a spontaneous pneumothorax, surgeons often recommend a bullectomy and pleurectomy. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax is most evident to people without any previous history of lung disease and in tall, thin men whose age is between 20 to 40 years old. But it can often occur in teenagers and young adults.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

A known lung disease is present in secondary spontaneous pneumothorax[5]. The most common cause is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, there are several diseases that may lead to spontaneous pneumothorax:

- COPD

- Tuberculosis

- Pneumonia

- Asthma

- Cystic fibrosis

- Lung cancer

- Interstitial lung disease

- Marfan's Syndrome

History

Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, a student of Rene Laennec, first recognised pneumothorax in 1803, and Laennec himself described the full clinical picture in 1819[6].

Prior to the advent of anti tuberculous medications, iatrogenic pneumothoraces were intentionally given to tuberculosis patients in an effort to collapse a lobe, or entire lung around a cavitating lesion. This was known as 'resting the lung' .

See also

- Emergency medicine

- Tension pneumothorax

- Pleural effusion

- Sucking chest wound:

External links

- A chest X-ray with a deep sulcus sign - learningradiology.com

- Blebinfo - Help, information, Forums and research on spontaneous pneumothorax

- Pneumothorax.org - Pneumothorax news, information and forums

- The Spontaneous Pneumothorax Patient Network - Info, Research & Support

- Music as a cause of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. An article from the journal Thorax detailing links between exposure to loud music and pneumothorax.

- Sucking chest wound:

- ↑ The American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary. "KMLE American Heritage Medical Dictionary definition of pneumothorax".

- ↑ Kong A (2003). "The deep sulcus sign". Radiology. 228 (2): 415–6. doi:10.1148/radiol.2282020524. PMID 12893899.

- ↑ Gordon R (1980). "The deep sulcus sign". Radiology. 136 (1): 25–7. PMID 7384513.

- ↑ Andrew K Chang, MD. "eMedicine.com: Pneumothorax, Iatrogenic, Spontaneous and Pneumomediastinum".

- ↑ http://www.lungusa.org/site/pp.asp?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=35772

- ↑ Laennec RTH. Traite de l'auscultation mediate et des maladies des poumons et du coeur. Part II. Paris, 1819.