Ménière's disease

| Ménière's disease | |

| ICD-10 | H81.0 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 386.0 |

| OMIM | 156000 |

| DiseasesDB | 8003 |

| MedlinePlus | 000702 |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Ménière's disease is a disorder of the inner ear that can affect hearing and balance. It is characterized by episodes of dizziness and tinnitus and progressive hearing loss, usually in one ear. It is caused by an increase in volume and pressure of the endolymph of the inner ear. It is named after the French physician Prosper Ménière, who first reported that vertigo was caused by inner ear disorders in an article published in 1861.[1]

Historical Background

Ménière's disease had been recognized prior to 1972, but it was still relatively vague and broad at the time. Committees at the Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology made set critera for diagnosing Ménière's, as well as defining two sub categories of Ménière's: cochlear (without vertigo) and vestibular (without deafness).

In 1972, the academy defined critera for diagnosing Ménière's disease as:

- Fluctuating, progressive, sensorineural deafness.

- Episodic, characteristic definitive spells of vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 24 hours with no unconsciousness, vestibular nystagmus always present.

- Usually tinnitus.

- Attacks are characterized by periods of remission and exacerbation.

In 1985, this list changed to alter wording, such as changing "deafness" to "hearing loss associated with tinnitus, characteristically of low frequencies" and requiring more than one attack of vertigo to diagnose. Finally in 1995, the list was again altered to allow for degrees of the disease:

- Certain - Definite disease with histopathological confirmation

- Definite - Requires two or more definitive episodes of vertigo with hearing loss plus tinnitus and/or aural fullness

- Probable - Only one definitive episode of vertigo and the other symptoms and signs

- Possible - Definitive vertigo with no associated hearing loss[2]

Cause

The exact cause of Ménière's disease is not known, but it is believed to be related to endolymphatic hydrops or excess fluid in the inner ear. It is thought that endolymphatic fluid bursts from its normal channels in the ear and flows into other areas causing damage. This may be related to swelling of the endolymphatic sac or other tissues in the vestibular system of the inner ear, which is responsible for the body's sense of balance. The symptoms may occur in the presence of a middle ear infection, head trauma or an upper respiratory tract infection, or by using aspirin, smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol. They may be further exacerbated by excessive consumption of caffeine and salt in some patients. Excessive levels of potassium in the body (usually caused by the consumption of potassium rich foods) may also exacerbate the symptoms.

It has also been proposed that Ménière's symptoms are the result of damage caused by a herpes virus [3][4]. Herpesviridae are present in a majority of the population in a dormant state. It is suggested that the virus is reactivated when the immune system is depressed due to a stressor such as trauma, infection or surgery (under general anaesthesia). Symptoms then develop as the virus degrades the structure of the inner ear.

Symptoms

The symptoms of Ménière's are variable; not all sufferers experience the same symptoms. However, so-called "classic Ménière's" is considered to comprise the following four symptoms:

- Periodic episodes of rotary vertigo (the abnormal sensation of movement) or dizziness.

- Fluctuating, progressive, unilateral (in one ear) or bilateral (in both ears) hearing loss, often initially in the lower frequency ranges.

- Unilateral or bilateral tinnitus (the perception of noises, often ringing, roaring, or whooshing), sometimes variable.

- A sensation of fullness or pressure in one or both ears.

Ménière's often begins with one symptom, and gradually progresses. A diagnosis may be made in the absence of all four classic symptoms.[5] However, having several symptoms at once is more conclusive than having each individual symptom had separate times.[6]

Attacks of vertigo can be severe, incapacitating, and unpredictable. In some patients, attacks of vertigo can last for hours or days, and may be accompanied by an increase in the loudness of tinnitus and temporary, albeit significant, hearing loss in the affected ear(s). Hearing may improve after an attack, but often becomes progressively worse. Vertigo attacks are sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and sweating.

Some sufferers experience what are informally known as "drop attacks" — a sudden, severe attack of dizziness or vertigo that causes the sufferer, if not seated, to fall. Patients may also experience the feeling of being pushed or pulled (Pulsion). Some patients may find it impossible to get up for some time, until the attack passes or medication takes effect. There is also the risk of injury from falling.

In addition to hearing loss, sounds can seem tinny or distorted, and patients can experience unusual sensitivity to noises (hyperacusis). Some sufferers also experience nystagmus, or uncontrollable rhythmical and jerky eye movements, usually in the horizontal plane, reflecting the essential role of the balance system in coordinating eye movements.

Other symptoms include so-called "brain fog" (temporary loss of short term memory, forgetfulness, and confusion), exhaustion and drowsiness, headaches, vision problems, and depression. Many of these latter symptoms are common to many chronic diseases.

Differential Diagnosis

| Diseases | Clinical manifestations | Para-clinical findings | Gold standard | Additional findings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Physical examination | ||||||||

| Lab Findings | Imaging | ||||||||

| Acute onset | Recurrency | Nystagmus | Hearing problems | ||||||

| Peripheral | |||||||||

| BPPV [7][8][9] |

+ | + | +/− | − | − | − |

| ||

| Vestibular neuritis [10] |

+ | +/− | + /−

(unilateral) |

− |

|

− | − |

| |

| HSV oticus [11][12][13][14] |

+ | +/− | − | +/− |

|

+ VZV antibody titres |

|

||

| Meniere disease [15][16] |

+/− | + | +/− | + (Progressive) | − |

|

|

||

| Labyrinthine concussion [17][18] |

+ | − | − | + | − |

|

| ||

| Perilymphatic fistula [19][20][21] |

+/− | + | − | + | − |

|

| ||

| Semicircular canal | +/− | + | − | +

(air-bone gaps on audiometry) |

− |

|

| ||

| Vestibular paroxysmia [24][25][26] |

+ | + | +/−

(Induced by hyperventilation) |

− |

|

− |

|

|

|

| Cogan syndrome [27][28][29] |

− | + | +/− | + | Increased ESR and cryoglobulins |

|

| ||

| Vestibular schwannoma [30][31] |

− | + | +/− | + |

|

− |

| ||

| Otitis media [32][33] |

+ | − | − | +/− |

|

Increased acute phase reactants |

|

| |

| Aminoglycoside toxicity [34] |

+ | − | − | + | − | − |

| ||

| Recurrent vestibulopathy [35][36] |

+ | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| |

| Central | |||||||||

| Vestibular migrain [37][38] |

– | + | +/− | +/− |

|

− |

|

|

|

| Epileptic vertigo [39] |

− | + | +/− | − |

|

− | − |

| |

| Multiple sclerosis [40][41][42] |

− | + | +/− | − | Elevated concentration of CSF oligoclonal bands |

|

|||

| Brain tumors [43] |

+/− | + | + | + | Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) may show cancerous cells |

|

| ||

| Cerebellar infarction/hemorrhage | + | − | ++/− | − | − |

| |||

| Brain stem ischemia | + | − | +/− | − |

|

− |

|

| |

| Chiari malformation [44][45] |

− | + | + | − |

|

− |

|

| |

| Parkinson [46][47][48] |

− | + | − | − | − |

|

| ||

ABBREVIATIONS

VZV= Varicella zoster virus, MRI= Magnetic resonance imaging, ESR= Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, EEG= Electroencephalogram, CSF= Cerebrospinal fluid, GPe= Globus pallidus externa, ICHD= International Classification of Headache Disorders

Diagnosis

Many disorders have symptoms similar to Ménière's. The diagnosis is usually established by clinical findings and medical history. However, a detailed oto-neurological examination, audiometry and head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan should be performed to exclude a tumour of the cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve) or superior canal dehiscence which would cause similar symptoms. Because there is no definitive test for Ménière's, it is only diagnosed when all other causes have been ruled out.

Ménière’s disease typically starts between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Men and women are affected in equal numbers.- American Academy of Otolaryngology−Head and Neck Surgery

Ménière's typically begins between the ages of 30 and 60 and affects men slightly more than women.[49][50]

Treatment

Initial treatment is aimed at both dealing with immediate symptoms and preventing recurrence of symptoms, and so will vary from patient to patient. Doctors may recommend vestibular training, methods for dealing with tinnitus, stress reduction, hearing aids to deal with hearing loss, and medication to alleviate nausea and symptoms of vertigo.

Several environmental and dietary changes are thought to reduce the frequency or severity of symptom outbreaks. Most patients are advised to adopt a low-sodium diet[6], typically one to two grams (1000-2000mg) at first, but diets as low as 400mg are not uncommon. Patients are advised to avoid caffeine, alcohol and tobacco, all of which can aggravate symptoms of Ménière's. Some recommend avoiding Aspartame. Patients are often prescribed a mild diuretic (sometimes vitamin B6). Many patients will have allergy testing done to see if they are candidate for allergy desensitization as allergies have been shown to aggravate Ménière's symptoms.[51]

Women may experience increased symptoms during pregnancy or shortly before menstruation, probably due to increased fluid retention.

Lipoflavonoid is also recommended for treatment by some doctors.[52]

Many patients consider fluorescent lighting to be a trigger for symptoms. The plausibility of this can be explained by how important a part vision plays in the overall mechanism of human balance.

Treatments aimed at lowering the pressure within the inner ear include antihistamines, anticholinergics, steroids, and diuretics.[6] A medical device that provides transtympanic micropressure pulses is now showing some promise and is becoming more widely used as a treatment for Ménière's.[54]

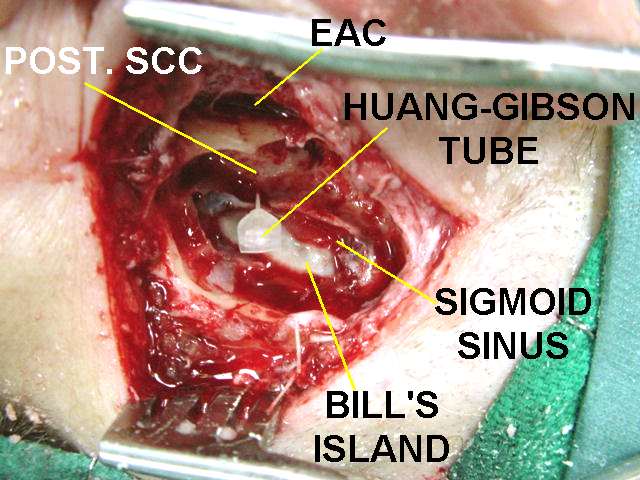

Surgery may be recommended if medical management does not control vertigo. Injection of steroid medication behind the eardrum, or surgery to decompress the endolymphatic sac may be used for symptom relief. Permanent surgical destruction of the balance part of the affected ear can be performed for severe cases if only one ear is affected. This can be achieved through chemical labyrinthectomy, in which a drug (such as gentamicin) that "kills" the vestibular apparatus is injected into the middle ear. The nerve to the balance portion of the inner ear can be cut (vestibular neurectomy), or the inner ear itself can be surgically removed (labyrinthectomy). These treatments eliminate vertigo, but because they are destructive, they are used only as a last resort. Typically balance returns to normal after these procedures, but hearing loss may continue to progress.[6]

The anti herpesvirus drug Aciclovir has also been used with some success to treat Ménière's Disease[3]. The likelihood of the effectiveness of the treatment was found to decrease with increasing duration of the disease possibly because the accumulation of viral damage to the inner ear over time meant that suppression of the virus made no significant difference to the symptoms. Morphological changes to the inner ear of Ménière's sufferers have also been found which it was considered likely to have resulted from attack by a herpes simplex virus[4]. It was considered possible that long term treatment with an acyclovir (greater than six months) would be required to produce an appreciable effect on symptoms. Herpes viruses have the ability to remain dormant in nerve cells by a process known as HHV Latency Associated Transcript. Continued administration of the drug should prevent reactivation of the virus and allow for the possibility of an improvement in symptoms. Another consideration is that different strains of a herpes virus can have different characteristics which may result in differences in the precise effects of the virus. Further confirmation that Aciclovir can have a positive effect on Ménière's symptoms has been reported[55].

Progression

Progression of Ménière's is unpredictable: symptoms may worsen, disappear altogether, or remain the same.

Sufferers whose Ménière's began with one or two of the classic symptoms may develop others with time. Attacks of vertigo can become worse and more frequent over time, resulting in loss of employment, loss of the ability to drive, and inability to travel. Some patients become largely housebound. Hearing loss can become more profound and may become permanent. Some patients become deaf in the affected ear. Tinnitus can also worsen over time. Some patients with unilateral symptoms, as many as fifty percent by some estimates, will develop symptoms in both ears. Some of these will become totally deaf.

Yet the disease may end spontaneously and never repeat again. Some sufferers find that after eight to ten years their vertigo attacks gradually become less frequent and less severe; in some patients they disappear completely. In some patients, symptoms of tinnitus will also disappear, and hearing will stabilize (though usually with some permanent loss).

See also

References

- ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ Beasley; Jones (December), "Meniere's disease: Evolution of a definition", The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 110 (12): 1107–13 Check date values in:

|date=, |year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Effectiveness of Acyclovir on Meniere's Syndrome III Observation of Clinical Symptoms in 301 cases," Mitsuo Shichinohe, M.D., Ph.D., The Sapporo Medical Journal, Vol. 68, No. 4-6, December, 1999.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Richard R. Gacek, MD and Mark R. Gacek, MD (2001). "Menière"s Disease as a Manifestation of Vestibular Ganglionitis". American Journal of Otolaryngology. 22 (4): 441–250. PMID 11464320.

- ↑ Hazell, Jonathan. "Information on Ménière's Syndrome"". Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Meniérè's disease". Maryland Hearing and Balance Center. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Lee SH, Kim JS (June 2010). "Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo". J Clin Neurol. 6 (2): 51–63. doi:10.3988/jcn.2010.6.2.51. PMC 2895225. PMID 20607044.

- ↑ Chang MB, Bath AP, Rutka JA (October 2001). "Are all atypical positional nystagmus patterns reflective of central pathology?". J Otolaryngol. 30 (5): 280–2. PMID 11771020.

- ↑ Dorresteijn PM, Ipenburg NA, Murphy KJ, Smit M, van Vulpen JK, Wegner I, Stegeman I, Grolman W (June 2014). "Rapid Systematic Review of Normal Audiometry Results as a Predictor for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 150 (6): 919–24. doi:10.1177/0194599814527233. PMID 24642523.

- ↑ Mandalà M, Nuti D, Broman AT, Zee DS (February 2008). "Effectiveness of careful bedside examination in assessment, diagnosis, and prognosis of vestibular neuritis". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 134 (2): 164–9. doi:10.1001/archoto.2007.35. PMID 18283159.

- ↑ Wackym, Phillip A. (1997). "Molecular Temporal Bone Pathology: II. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (Herpes Zoster Oticus)". The Laryngoscope. 107 (9): 1165–1175. doi:10.1097/00005537-199709000-00003. ISSN 0023-852X.

- ↑ Zhu, S.; Pyatkevich, Y. (2014). "Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II". Neurology. 82 (18): 1664–1664. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000388. ISSN 0028-3878.

- ↑ Mishell JH, Applebaum EL (February 1990). "Ramsay-Hunt syndrome in a patient with HIV infection". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 102 (2): 177–9. doi:10.1177/019459989010200215. PMID 2113244.

- ↑ Tada, Yuichiro; Aoyagi, Masaru; Tojima, Hitoshi; Inamura, Hiroo; Saito, Osamu; Maeyama, Hiroyuki; Kohsyu, Hidehiro; Koike, Yoshio (2009). "Gd-DTPA Enhanced MRI in Ramsay Hunt Syndrome". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 114 (sup511): 170–174. doi:10.3109/00016489409128326. ISSN 0001-6489.

- ↑ Watanabe, Isamu (1980). "Ménière's Disease". ORL. 42 (1–2): 20–45. doi:10.1159/000275477. ISSN 1423-0275.

- ↑ Saeed SR (January 1998). "Fortnightly review. Diagnosis and treatment of Ménière's disease". BMJ. 316 (7128): 368–72. PMC 2665527. PMID 9487176.

- ↑ Dürrer, J.; Poláčková, J. (1971). "Labyrinthine Concussion". ORL. 33 (3): 185–190. doi:10.1159/000274994. ISSN 1423-0275.

- ↑ Choi MS, Shin SO, Yeon JY, Choi YS, Kim J, Park SK (April 2013). "Clinical characteristics of labyrinthine concussion". Korean J Audiol. 17 (1): 13–7. doi:10.7874/kja.2013.17.1.13. PMC 3936518. PMID 24653897.

- ↑ Fox, Eileen J.; Balkany, Thomas J.; Arenberg, Kaufman (1988). "The Tullio Phenomenon and Perilymph Fistula". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 98 (1): 88–89. doi:10.1177/019459988809800115. ISSN 0194-5998.

- ↑ Casselman JW (February 2002). "Diagnostic imaging in clinical neuro-otology". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 15 (1): 23–30. PMID 11796947.

- ↑ Seltzer S, McCabe BF (January 1986). "Perilymph fistula: the Iowa experience". Laryngoscope. 96 (1): 37–49. PMID 3941579.

- ↑ Lempert T, von Brevern M (February 2005). "Episodic vertigo". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 18 (1): 5–9. PMID 15655395.

- ↑ Watson SR, Halmagyi GM, Colebatch JG (February 2000). "Vestibular hypersensitivity to sound (Tullio phenomenon): structural and functional assessment". Neurology. 54 (3): 722–8. PMID 10680810.

- ↑ Hufner, K.; Barresi, D.; Glaser, M.; Linn, J.; Adrion, C.; Mansmann, U.; Brandt, T.; Strupp, M. (2008). "Vestibular paroxysmia: Diagnostic features and medical treatment". Neurology. 71 (13): 1006–1014. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000326594.91291.f8. ISSN 0028-3878.

- ↑ Strupp M, von Stuckrad-Barre S, Brandt T, Tonn JC (February 2013). "Teaching neuroimages: Compression of the eighth cranial nerve causes vestibular paroxysmia". Neurology. 80 (7): e77. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281cc2c. PMID 23400324.

- ↑ Hüfner K, Barresi D, Glaser M, Linn J, Adrion C, Mansmann U, Brandt T, Strupp M (September 2008). "Vestibular paroxysmia: diagnostic features and medical treatment". Neurology. 71 (13): 1006–14. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000326594.91291.f8. PMID 18809837.

- ↑ Vollertsen RS (May 1990). "Vasculitis and Cogan's syndrome". Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 16 (2): 433–9. PMID 2189159.

- ↑ Hughes, Gordon B.; Kinney, Sam E.; Barna, Barbara P.; Tomsak, Robert L.; Calabrese, Leonard H. (1983). "Autoimmune reactivity in Cogan's syndrome: A preliminary report". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 91 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1177/019459988309100106. ISSN 0194-5998.

- ↑ Majoor, M. H. J. M.; Albers, F. W. J.; Casselman, J. W. (2009). "Clinical Relevance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography in Cogan's Syndrome". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 113 (5): 625–631. doi:10.3109/00016489309135875. ISSN 0001-6489.

- ↑ Robert W. Foley, Shahram Shirazi, Robert M. Maweni, Kay Walsh, Rory McConn Walsh, Mohsen Javadpour & Daniel Rawluk (2017). "Signs and Symptoms of Acoustic Neuroma at Initial Presentation: An Exploratory Analysis". Cureus. 9 (11): e1846. doi:10.7759/cureus.1846. PMID 29348989. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ E. P. Lin & B. T. Crane (2017). "The Management and Imaging of Vestibular Schwannomas". AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 38 (11): 2034–2043. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A5213. PMID 28546250. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Ear infection - acute: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia".

- ↑ Rettig E, Tunkel DE (2014). "Contemporary concepts in management of acute otitis media in children". Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 47 (5): 651–72. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2014.06.006. PMC 4393005. PMID 25213276.

- ↑ Ernfors P, Duan ML, ElShamy WM, Canlon B (April 1996). "Protection of auditory neurons from aminoglycoside toxicity by neurotrophin-3". Nat. Med. 2 (4): 463–7. PMID 8597959.

- ↑ Oh AK, Lee H, Jen JC, Corona S, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW (May 2001). "Familial benign recurrent vertigo". Am. J. Med. Genet. 100 (4): 287–91. PMID 11343320.

- ↑ Rutka JA, Barber HO (April 1986). "Recurrent vestibulopathy: third review". J Otolaryngol. 15 (2): 105–7. PMID 3712538.

- ↑ "The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition". Cephalalgia. 24 Suppl 1: 9–160. 2004. PMID 14979299.

- ↑ Absinta M, Rocca MA, Colombo B, Copetti M, De Feo D, Falini A, Comi G, Filippi M (December 2012). "Patients with migraine do not have MRI-visible cortical lesions". J. Neurol. 259 (12): 2695–8. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6571-x. PMID 22714135.

- ↑ Tarnutzer AA, Lee SH, Robinson KA, Kaplan PW, Newman-Toker DE (April 2015). "Clinical and electrographic findings in epileptic vertigo and dizziness: a systematic review". Neurology. 84 (15): 1595–604. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001474. PMC 4408281. PMID 25795644.

- ↑ McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, Goodkin D, Hartung HP, Lublin FD, McFarland HF, Paty DW, Polman CH, Reingold SC, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Sibley W, Thompson A, van den Noort S, Weinshenker BY, Wolinsky JS (July 2001). "Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 50 (1): 121–7. PMID 11456302.

- ↑ Barrett L, Drayer B, Shin C (January 1985). "High-resolution computed tomography in multiple sclerosis". Ann. Neurol. 17 (1): 33–8. doi:10.1002/ana.410170109. PMID 3985583.

- ↑ Fazekas F, Barkhof F, Filippi M, Grossman RI, Li DK, McDonald WI, McFarland HF, Paty DW, Simon JH, Wolinsky JS, Miller DH (August 1999). "The contribution of magnetic resonance imaging to the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 53 (3): 448–56. PMID 10449103.

- ↑ Dunniway, Heidi M.; Welling, D. Bradley (2016). "Intracranial Tumors Mimicking Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 118 (4): 429–436. doi:10.1177/019459989811800401. ISSN 0194-5998.

- ↑ Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C (May 2004). "Diagnosis of Chiari I malformation and related syringomyelia: radiological and neurophysiological studies". Childs Nerv Syst. 20 (5): 332–5. doi:10.1007/s00381-003-0880-4. PMID 15034729.

- ↑ Sarnat HB (2008). "Disorders of segmentation of the neural tube: Chiari malformations". Handb Clin Neurol. 87: 89–103. doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(07)87006-0. PMID 18809020.

- ↑ van Wensen, E.; van Leeuwen, R.B.; van der Zaag-Loonen, H.J.; Masius-Olthof, S.; Bloem, B.R. (2013). "Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 19 (12): 1110–1112. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.07.024. ISSN 1353-8020.

- ↑ Steiner I, Gomori JM, Melamed E (1985). "Features of brain atrophy in Parkinson's disease. A CT scan study". Neuroradiology. 27 (2): 158–60. PMID 3990948.

- ↑ Kosta P, Argyropoulou MI, Markoula S, Konitsiotis S (January 2006). "MRI evaluation of the basal ganglia size and iron content in patients with Parkinson's disease". J. Neurol. 253 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1007/s00415-005-0914-9. PMID 15981079.

- ↑ p.550, The Johns Hopkins Complete Home Guide to Symptoms & Remedies, ed. Simeon Margolis, Black Dog & Levanthal Publishers (2004).

- ↑ U.K. NHS

- ↑ Derebery MJ (2000). "Allergic management of Meniere's disease: an outcome study". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 122 (2): 174–82. PMID 10652386.

- ↑ Williams HL, Maher FT, Corbin KB, et al: Eriodictyol glycoside in the treatment of Meniere’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol72:1082, 1963.

- ↑ http://www.ghorayeb.com

- ↑ Rajan GP, Din S, Atlas MD (2005). "Long-term effects of the Meniett device in Ménière's disease: the Western Australian experience". The Journal of laryngology and otology. 119 (5): 391–5. doi:10.1258/0022215053945868. PMID 15949105.

- ↑ Gacek RR (2008). "Evidence for a viral neuropathy in recurrent vertigo". ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 70 (1): 6–14. PMID 18235200.

Template:Diseases of the ear and mastoid process

cs:Ménierova nemoc

de:Morbus Menière

hr:Ménièreova bolest

it:Sindrome di Ménière

he:מחלת מנייר

nl:Ziekte van Ménière

no:Ménières sykdom

fi:Ménièren tauti

sv:Ménières sjukdom

Template:SIB