Adrenal hemorrhage: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

MeshID = D014884 | | MeshID = D014884 | | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Adrenal hemorrhage}} | |||

{{CMG}} ; '''Associate Editor-In-Chief:''' {{CZ}} | {{CMG}} ; '''Associate Editor-In-Chief:''' {{CZ}} | ||

{{SK}} Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) | {{SK}} Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) | ||

Revision as of 20:48, 21 August 2012

| Adrenal hemorrhage | |

| |

|---|---|

| Ultrasonography: Adrenal hemorrhage. Image courtesy of RadsWiki | |

| ICD-10 | A39.1, E35.1 |

| ICD-9 | 036.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 29316 |

| MeSH | D014884 |

|

Adrenal hemorrhage Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Adrenal hemorrhage On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Adrenal hemorrhage |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2] Synonyms and keywords: Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (WFS)

Overview

Adrenal hemorrhage is massive, usually bilateral, hemorrhage into the adrenal glands caused by fulminant meningococcemia.[1] WFS is characterised by overwhelming bacterial infection, rapidly progressive hypotension leading to shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with widespread purpura, particularly of the skin, and rapidly developing adrenocortical insufficiency associated with massive bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis

- Adrenal adenoma

- Adrenal carcinoma

- Adrenal metastases

- Adrenal myelolipoma

- Genitourinary tuberculosis

- Neuroblastoma

Epidemiology

Meningococcus is another term for the bacterial species Neisseria meningitidis, which causes the type of meningitis which usually underlies this syndrome. Meningococcal meningitis occurs most commonly in children and young adults, and can occur in epidemics. In the United States it is the cause of about 20% of meningitis cases. At one time it was common among military recruits, but administration of the preventive meningococcal vaccine has greatly reduced this number. Freshman college students living in dormitory housing who have not been vaccinated are another risk group.

WFS can also be caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae infections, a common bacterial pathogen typically associated with meningitis in the adult and elderly population.[1] Staphylococcus aureus has recently also been implicated in pediatric WFS.[2]

Routine vaccination against meningococcus is recommended for people who have poor splenic function (who, for example, have had their spleen removed or who have sickle-cell anemia which damages the spleen), or who have certain immune disorders, such as complement deficiency.[3]

Etiology

Adrenal hemorrhage occurs secondary to both traumatic conditions and atraumatic conditions. Atraumatic causes of adrenal hemorrhage include:

- Stress

- Hemorrhagic diathesis or coagulopathy

- Neonatal stress

- Underlying adrenal tumors

- Idiopathic disease

Historical

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome is named after Rupert Waterhouse (1873–1958), an English physician, and Carl Friderichsen (1886–1979), a Danish pediatrician, who wrote papers on the syndrome, which had been previously described.[4][5]

Symptoms

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome is the most severe form of meningococcal septicemia.

The onset of the illness is nonspecific with fever, rigors, vomiting and headache. Soon a rash appears; first macular, not much different from the rose spots of typhoid, and rapidly becoming petechial and purpuric with a dusky gray color. Hypotension is the rule and rapidly leads to septic shock. The cyanosis of extremities can be impressive and the patient is very prostrated or comatose. In this form of meningococcal disease, meningitis generally does not occur.

There is hypoglycemia with hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, and the Synachten test demonstrates the acute suprarenal failure. Leukocytosis need not to be extreme and in fact leukopenia may be seen and it is a very poor prognostic sign. CRP levels can be elevated or almost normal. Thrombocytopenia is sometimes extreme, with alteration in PT and PTT suggestive of DIC. Acidosis and acute renal failure can be seen as in any severe sepsis.

Meningococci can be readily cultured from blood or CSF, and can sometimes be seen in smears of cutaneous lesions.

Diagnosis

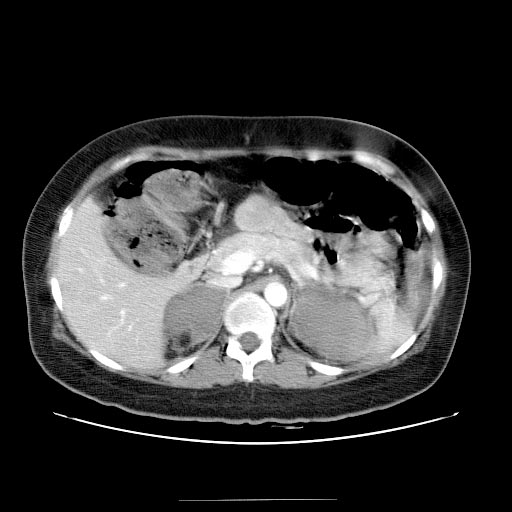

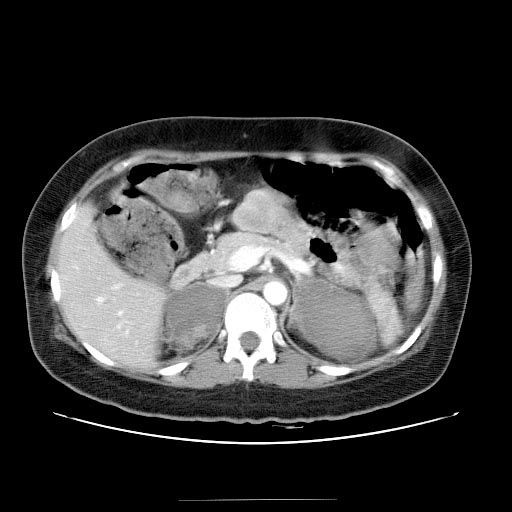

Computed Tomography

- Adrenal hematomas characteristically appear round or oval

- Stranding of the periadrenal fat is evident as well.

- Attenuation value of adenal hematoma depends on its age.

- Acute to subacute hematomas contain areas of high attenuation that usually range from 50 to 90 HU.

- Adrenal hematomas decrease in size and attenuation over time, and most resolve completely.

- Adrenal hematoma may calcify after 1 year.

- Organized chronic adrenal hematoma appears as a mass with a hypoattenuating center with or without calcifications. Such masses are termed adrenal pseudocysts.

-

Computed Tomography: Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage

-

Computed Tomography: Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage

-

Computed Tomography: Follow up scan

-

Computed Tomography: Follow up scan

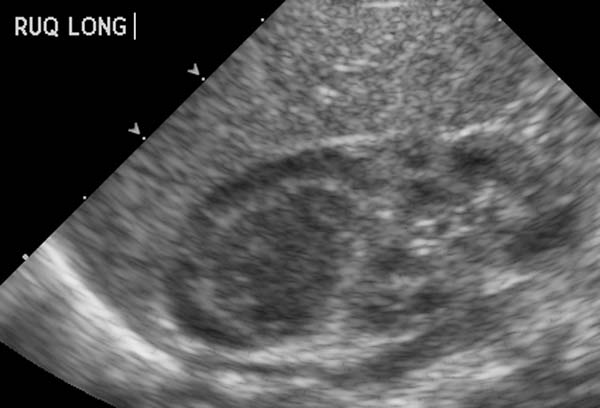

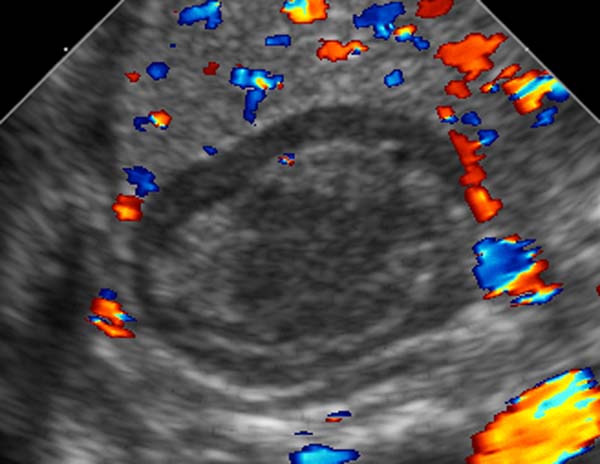

Ultrasonography

- Pattern of echogenicity of an adrenal hematoma depends on its age

- Early-stage hematoma appears solid with diffuse or inhomogeneous echogenicity.

- As liquefaction occurs, the mass demonstrates mixed echogenicity with a central hypoechoic region and eventually becomes completely anechoic and cystlike.

- Calcifications may be seen in the walls of the hematoma as early as 1–2 weeks after onset and gradually compact as the blood is absorbed.

- Color Doppler and power Doppler imaging allow confirmation of the avascular nature of the mass.

-

Ultrasonography: Adrenal hemorrhage

-

Ultrasonography: Adrenal hemorrhage

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Acute stage (less than 7 days after onset): the hematoma typically appears isointense or slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images and markedly hypointense on T2-weighted images.

- Subacute stage (7 days to 7 weeks after onset): the hematoma appears hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images.

- Chronic stage (which typically begins 7 weeks after onset): a hypointense rim is present on T1- and T2-weighted images, which is attributed to hemosiderin deposition and the presence of a fibrous capsule.

Treatment

Fulminant meningococcemia is a medical emergency and need to be treated with adequate antibiotics as fast as possible. Benzylpenicillin is the drug of choice with chloramphenicol as a good alternative in allergic patients. Hydrocortisone can sometimes reverse the hypoadrenal shock. Sometimes plastic surgery and grafting is needed to deal with tissue necrosis.

Ceftriaxone is an antibiotic commonly employed today.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N (2005). Robins and Coltran: Pathological Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Elsevier. pp. pp. 1214&ndash, 5. ISBN 978-0721601878.

- ↑ Adem P, Montgomery C, Husain A, Koogler T, Arangelovich V, Humilier M, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R (2005). "Staphylococcus aureus sepsis and the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in children". N Engl J Med. 353 (12): 1245–51. PMID 16177250.

- ↑ Rosa D, Pasqualotto A, de Quadros M, Prezzi S (2004). "Deficiency of the eighth component of complement associated with recurrent meningococcal meningitis--case report and literature review". Braz J Infect Dis. 8 (4): 328–30. PMID 15565265.

- ↑ Waterhouse R (1911). "A case of suprarenal apoplexy". Lancet. 1: 577&ndash, 8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)60988-7.

- ↑ Friderichsen C (1918). "Nebennierenapoplexie bei kleinen Kindern". Jahrb Kinderheilk. 87: 109&ndash, 25.