Sandbox john2: Difference between revisions

Joao Silva (talk | contribs) |

Joao Silva (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==In Progress== | ==In Progress== | ||

== | ==Pathophysionology== | ||

A number of | Worldwide, 1-2 million persons are permanently disabled as a result of Hansen's disease. However, persons receiving [[antibiotic treatment]] or having completed treatment are considered free of active infection. Although the mode of [[transmission]] of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that [[M. leprae]] is usually spread from person to person in [[respiratory]] droplets. | ||

The exact mechanism of transmission of leprosy is not known: prolonged close contact and transmission by nasal droplet have both been proposed, and, while the latter fits the pattern of disease, both remain unproved.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Reich CV |title=Leprosy: cause, transmission, and a new theory of pathogenesis |journal=Rev. Infect. Dis. |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=590-4 |year=1987 |pmid=3299638 |doi=}}</ref> The only other animals besides humans to contract leprosy are the armadillo, chimpanzees, sooty mangabeys, and Crab-eating Macaque.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rojas-Espinosa O, Løvik M |title=Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepraemurium infections in domestic and wild animals |journal=Rev. - Off. Int. Epizoot. |volume=20 |issue=1 |pages=219-51 |year=2001 |pmid=11288514 |doi=}}</ref> The bacterium can also be grown in the laboratory by injection into the footpads of mice.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hastings RC, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Franzblau SG |title=Leprosy |journal=Clin. Microbiol. Rev. |volume=1 |issue=3 |pages=330-48 |year=1988 |pmid=3058299 |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=3058299}}</ref> There is evidence that not all people who are infected with ''M. leprae'' develop leprosy, and genetic factors have long been thought to play a role, due to the observation of clustering of leprosy around certain families, and the failure to understand why certain individuals develop lepromatous leprosy while others develop other types of leprosy.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Alcaïs A, Mira M, Casanova JL, Schurr E, Abel L |title=Genetic dissection of immunity in leprosy |journal=Curr. Opin. Immunol. |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=44-8 |year=2005 |pmid=15653309 |doi=10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.006}}</ref> However, the role of genetic factors is not clear in determining this clinical expression. In addition, malnutrition and possible prior exposure to other environmental [[mycobacteria]] may play a role in development of the overt disease. | |||

The most widely-held belief is that the disease is transmitted by contact between infected persons and healthy persons.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kaur H, Van Brakel W |title=Dehabilitation of leprosy-affected people--a study on leprosy-affected beggars |journal=Leprosy review |volume=73 |issue=4 |pages=346-55 |year=2002 |pmid=12549842 |doi=}}</ref> In general, closeness of contact is related to the dose of infection, which in turn is related to the occurrence of disease. Of the various situations that promote close contact, contact within the household is the only one that is easily identified, although the actual incidence among contacts and the relative risk for them appear to vary considerably in different studies. In [[Incidence (epidemiology)|incidence studies]], infection rates for contacts of lepromatous leprosy have varied from 6.2 per 1000 per year in Cebu, Philippines<ref name=Doull_1942>{{cite journal | author = Doull JA, Guinto RA, Rodriguez RS, et al. | title = The incidence of leprosy in Cordova and Talisay, Cebu, Philippines | journal = International Journal of Leprosy | year = 1942 | volume = 10 | pages = 107–131 | url= }}</ref> to 55.8 per 1000 per year in a part of Southern India.<ref name=Noordeen_1978>{{cite journal |author=Noordeen S, Neelan P |title=Extended studies on chemoprophylaxis against leprosy |journal=Indian J Med Res |volume=67 |issue= |pages=515-27 |year=1978 |pmid=355134}}</ref> | |||

Two exit routes of ''M. leprae'' from the human body often described are the skin and the nasal mucosa, although their relative importance is not clear. It is true that lepromatous cases show large numbers of organisms deep down in the [[dermis]]. However, whether they reach the skin surface in sufficient numbers is doubtful. Although there are reports of [[Acid-fast|acid-fast bacilli]] being found in the desquamating [[epithelium]] of the skin, Weddell ''et al'' have reported that they could not find any acid-fast bacilli in the [[epidermis]], even after examining a very large number of specimens from patients and contacts.<ref name=Weddell_1963>{{cite journal |author=Weddell G, Palmer E |title=The pathogenesis of leprosy. An experimental approach |journal=Leprosy Review |volume=34 |issue= |pages=57-61 |year=1963 |pmid=13999438}}</ref> In a recent study, Job ''et al'' found fairly large numbers of ''M. leprae'' in the superficial [[keratin]] layer of the skin of lepromatous leprosy patients, suggesting that the organism could exit along with the [[Sebaceous gland|sebaceous]] secretions.<ref name=Job_1999>{{cite journal |author=Job C, Jayakumar J, Aschhoff M |title="Large numbers" of Mycobacterium leprae are discharged from the intact skin of lepromatous patients; a preliminary report |journal=Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis |volume=67 |issue=2 |pages=164-7 |year=1999 |pmid=10472371}}</ref> | |||

The importance of the [[nasal mucosa]] was recognized by Schäffer, particularly that of the ulcerated mucosa. <ref name=Schaffer_1898>''Arch Dermato Syphilis'' 1898; 44:159–174</ref> The quantity of bacilli from nasal mucosal lesions in lepromatous leprosy was demonstrated by Shepard as large, with counts ranging from 10,000 to 10,000,000.<ref name=Shepard_1960>{{cite journal |author=Shepard C |title=Acid-fast bacilli in nasal excretions in leprosy, and results of inoculation of mice |journal=Am J Hyg |volume=71 |issue= |pages=147-57 |year=1960 |pmid=14445823}}</ref> Pedley reported that the majority of lepromatous patients showed leprosy bacilli in their nasal secretions as collected through blowing the nose.<ref name=Pedley_1973>{{cite journal |author=Pedley J |title=The nasal mucus in leprosy |journal=Lepr Rev |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=33-5 |year=1973 |pmid=4584261}}</ref> Davey and Rees indicated that nasal secretions from lepromatous patients could yield as much as 10 million viable organisms per day.<ref name=Davey_1974>{{cite journal |author=Davey T, Rees R |title=The nasal dicharge in leprosy: clinical and bacteriological aspects |journal=Lepr Rev |volume=45 |issue=2 |pages=121-34 |year=1974 |pmid=4608620}}</ref> | |||

The entry route of ''M. leprae'' into the human body is also not definitely known. The two seriously considered are the skin and the upper respiratory tract. While older research dealt with the skin route, recent research has increasingly favored the respiratory route. Rees and McDougall succeeded in the experimental transmission of leprosy through aerosols containing ''M. leprae'' in immune-suppressed mice, suggesting a similar possibility in humans.<ref name=Rees_1977>{{cite journal |author=Rees R, McDougall A |title=Airborne infection with Mycobacterium leprae in mice |journal=J Med Microbiol |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=63-8 |year=1977 |pmid=320339}}</ref> Successful results have also been reported on experiments with [[nude mice]] when ''M. leprae'' were introduced into the nasal cavity by topical application. <ref name=Chehl_1985>{{cite journal |author=Chehl S, Job C, Hastings R |title=Transmission of leprosy in nude mice |journal=Am J Trop Med Hyg |volume=34 |issue=6 |pages=1161-6 |year=1985 |pmid=3914846}}</ref> In summary, entry through the respiratory route appears the most probable route, although other routes, particularly broken skin, cannot be ruled out. The CDC notes the following assertion about the transmission of the disease: "''Although the mode of transmission of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that ''M. leprae'' is usually spread from person to person in respiratory droplets''."<ref name=CDC_2005>{{cite web | title = Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) | work = Technical Information | publisher = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | date = 2005-10-12 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/hansens_t.htm | accessdate = 2007-03-22}}</ref> | |||

In leprosy both the reference points for measuring the [[incubation period]] and the times of infection and onset of disease are difficult to define; the former because of the lack of adequate immunological tools and the latter because of the disease's slow onset. Even so, several investigators have attempted to measure the incubation period for leprosy. The minimum incubation period reported is as short as a few weeks and this is based on the very occasional occurrence of leprosy among young infants. <ref name=Montestruc_1954>{{cite journal |author=Montestruc E, Berdonneau R |title=2 New cases of leprosy in infants in Martinique. |journal=Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales |volume=47 |issue=6 | language = French | pages=781-3 |year=1954 |pmid=14378912}}</ref> The maximum incubation period reported is as long as 30 years, or over, as observed among war veterans known to have been exposed for short periods in endemic areas but otherwise living in non-endemic areas. It is generally agreed that the average incubation period is between 3 to 5 years. | |||

''Common nerves affected by the disease include:'' | |||

::* Ulnar nerve | |||

::* Median nerve | |||

::* Common peroneal nerve | |||

::* Posterior tibial nerve | |||

::* Facial nerve | |||

::* Radial cutaneous nerve | |||

::* Great auricular nerve | |||

===Transmission=== | |||

Although the mode of transmission of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that ''M. leprae'' is usually spread from person to person in respiratory droplets.<ref>City of Houston Government Center, Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Hansen's disease (leprosy) Retrieved from http://www.houstontx.gov/health/ComDisease/hansens.html</ref> Studies have shown that leprosy can be transmitted to humans by [[armadillos]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Probable Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southern United States|url=http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1010536|publisher=The New England Journal of Medicine |accessdate=April 28, 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.cnn.com/2011/HEALTH/04/27/armadillos.spreading.leprosy/index.html?hpt=Sbin | work=CNN | title=Armadillos linked to leprosy in humans | date=2011-04-28}}</ref><ref name="Truman 2011">{{cite journal |last=Truman |first=Richard W. |title=Probable Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southern United States |journal=The New England Journal of Medicine |volume=364 |year=2011 |month=April |pages=1626–1633 |publisher=Massachusetts Medical Society |url=http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1010536 |accessdate=3 May 2011 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa1010536 |last2=Singh |first2=Pushpendra |last3=Sharma |first3=Rahul |last4=Busso |first4=Philippe |last5=Rougemont |first5=Jacques |last6=Paniz-Mondolfi |first6=Alberto |last7=Kapopoulou |first7=Adamandia |last8=Brisse |first8=Sylvain |last9=Scollard |first9=David M. |issue=17 |pmid=21524213 |pmc=3138484}}</ref> Leprosy is not known to be either sexually transmitted or highly infectious after treatment. Approximately 95% of people are [[natural immunity|naturally immune]] and sufferers are no longer infectious after as little as 2 weeks of treatment.<ref>{{cite web |title=About leprosy: frequently asked questions|url=http://www.leprosy.org/leprosy-faqs|publisher=American Leprosy Missions, Inc |accessdate=October 2, 2012}}</ref> | |||

The minimum [[incubation period]] reported is as short as a few weeks, based on the very occasional occurrence of leprosy among young infants. The maximum incubation period reported is as long as 30 years, or over, as observed among war veterans known to have been exposed for short periods in endemic areas but otherwise living in non-endemic areas. It is generally agreed that the average incubation period is between three and five years. | |||

==Random notes== | ==Random notes== | ||

Revision as of 23:40, 6 July 2014

In Progress

Pathophysionology

Worldwide, 1-2 million persons are permanently disabled as a result of Hansen's disease. However, persons receiving antibiotic treatment or having completed treatment are considered free of active infection. Although the mode of transmission of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that M. leprae is usually spread from person to person in respiratory droplets.

The exact mechanism of transmission of leprosy is not known: prolonged close contact and transmission by nasal droplet have both been proposed, and, while the latter fits the pattern of disease, both remain unproved.[1] The only other animals besides humans to contract leprosy are the armadillo, chimpanzees, sooty mangabeys, and Crab-eating Macaque.[2] The bacterium can also be grown in the laboratory by injection into the footpads of mice.[3] There is evidence that not all people who are infected with M. leprae develop leprosy, and genetic factors have long been thought to play a role, due to the observation of clustering of leprosy around certain families, and the failure to understand why certain individuals develop lepromatous leprosy while others develop other types of leprosy.[4] However, the role of genetic factors is not clear in determining this clinical expression. In addition, malnutrition and possible prior exposure to other environmental mycobacteria may play a role in development of the overt disease.

The most widely-held belief is that the disease is transmitted by contact between infected persons and healthy persons.[5] In general, closeness of contact is related to the dose of infection, which in turn is related to the occurrence of disease. Of the various situations that promote close contact, contact within the household is the only one that is easily identified, although the actual incidence among contacts and the relative risk for them appear to vary considerably in different studies. In incidence studies, infection rates for contacts of lepromatous leprosy have varied from 6.2 per 1000 per year in Cebu, Philippines[6] to 55.8 per 1000 per year in a part of Southern India.[7]

Two exit routes of M. leprae from the human body often described are the skin and the nasal mucosa, although their relative importance is not clear. It is true that lepromatous cases show large numbers of organisms deep down in the dermis. However, whether they reach the skin surface in sufficient numbers is doubtful. Although there are reports of acid-fast bacilli being found in the desquamating epithelium of the skin, Weddell et al have reported that they could not find any acid-fast bacilli in the epidermis, even after examining a very large number of specimens from patients and contacts.[8] In a recent study, Job et al found fairly large numbers of M. leprae in the superficial keratin layer of the skin of lepromatous leprosy patients, suggesting that the organism could exit along with the sebaceous secretions.[9]

The importance of the nasal mucosa was recognized by Schäffer, particularly that of the ulcerated mucosa. [10] The quantity of bacilli from nasal mucosal lesions in lepromatous leprosy was demonstrated by Shepard as large, with counts ranging from 10,000 to 10,000,000.[11] Pedley reported that the majority of lepromatous patients showed leprosy bacilli in their nasal secretions as collected through blowing the nose.[12] Davey and Rees indicated that nasal secretions from lepromatous patients could yield as much as 10 million viable organisms per day.[13]

The entry route of M. leprae into the human body is also not definitely known. The two seriously considered are the skin and the upper respiratory tract. While older research dealt with the skin route, recent research has increasingly favored the respiratory route. Rees and McDougall succeeded in the experimental transmission of leprosy through aerosols containing M. leprae in immune-suppressed mice, suggesting a similar possibility in humans.[14] Successful results have also been reported on experiments with nude mice when M. leprae were introduced into the nasal cavity by topical application. [15] In summary, entry through the respiratory route appears the most probable route, although other routes, particularly broken skin, cannot be ruled out. The CDC notes the following assertion about the transmission of the disease: "Although the mode of transmission of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that M. leprae is usually spread from person to person in respiratory droplets."[16]

In leprosy both the reference points for measuring the incubation period and the times of infection and onset of disease are difficult to define; the former because of the lack of adequate immunological tools and the latter because of the disease's slow onset. Even so, several investigators have attempted to measure the incubation period for leprosy. The minimum incubation period reported is as short as a few weeks and this is based on the very occasional occurrence of leprosy among young infants. [17] The maximum incubation period reported is as long as 30 years, or over, as observed among war veterans known to have been exposed for short periods in endemic areas but otherwise living in non-endemic areas. It is generally agreed that the average incubation period is between 3 to 5 years.

Common nerves affected by the disease include:

- Ulnar nerve

- Median nerve

- Common peroneal nerve

- Posterior tibial nerve

- Facial nerve

- Radial cutaneous nerve

- Great auricular nerve

Transmission

Although the mode of transmission of Hansen's disease remains uncertain, most investigators think that M. leprae is usually spread from person to person in respiratory droplets.[18] Studies have shown that leprosy can be transmitted to humans by armadillos.[19][20][21] Leprosy is not known to be either sexually transmitted or highly infectious after treatment. Approximately 95% of people are naturally immune and sufferers are no longer infectious after as little as 2 weeks of treatment.[22]

The minimum incubation period reported is as short as a few weeks, based on the very occasional occurrence of leprosy among young infants. The maximum incubation period reported is as long as 30 years, or over, as observed among war veterans known to have been exposed for short periods in endemic areas but otherwise living in non-endemic areas. It is generally agreed that the average incubation period is between three and five years.

Random notes

Acute Pharmacotherapy

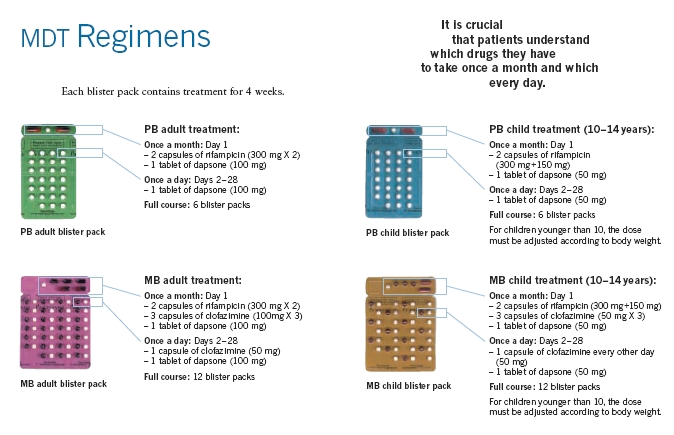

Until the development of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine in the 1940s, there was no effective cure for leprosy. However, dapsone is only weakly bactericidal against M. leprae and it was considered necessary for patients to take the drug indefinitely. Moreover, when dapsone was used alone, the M. leprae population quickly evolved antibiotic resistance; by the 1960s, the world's only known anti-leprosy drug became virtually useless.

The search for more effective anti-leprosy drugs to dapsone led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[23] Later, Shantaram Yawalkar and colleagues formulated a combined therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial resistance.[24] Multidrug therapy (MDT) and combining all three drugs was first recommended by a WHO Expert Committee in 1981. These three anti-leprosy drugs are still used in the standard MDT regimens. None of them are used alone because of the risk of developing resistance.

Because this treatment is quite expensive, it was not quickly adopted in most endemic countries. In 1985 leprosy was still considered a public health problem in 122 countries. The 44th World Health Assembly (WHA), held in Geneva in 1991 passed a resolution to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem by the year 2000 — defined as reducing the global prevalence of the disease to less than 1 case per 100,000. At the Assembly, the World Health Organization (WHO) was given the mandate to develop an elimination strategy by its member states, based on increasing the geographical coverage of MDT and patients’ accessibility to the treatment.

The WHO Study Group's report on the Chemotherapy of Leprosy in 1993 recommended two types of standard MDT regimen be adapted.[25] The first was a 24-month treatment for multibacillary (MB or lepromatous) cases using rifampicin, clofazimine, and dapsone. The second was a six-month treatment for paucibacillary (PB or tuberculoid) cases, using rifampicin and dapsone. At the First International Conference on the Elimination of Leprosy as a Public Health Problem, held in Hanoi the next year, the global strategy was endorsed and funds provided to WHO for the procurement and supply of MDT to all endemic countries.

Since 1995, WHO has supplied all endemic countries with free MDT in blister packs, supplied through Ministries of Health. This free provision was extended in 2000, and again in 2005, and will run until at least the end of 2010. At the national level, non-government organisations (NGOs) affiliated to the national programme will continue to be provided with an appropriate free supply of this MDT by the government.

MDT remains highly effective and patients are no longer infectious after the first monthly dose. It is safe and easy to use under field conditions due to its presentation in calendar blister packs. Relapse rates remain low, and there is no known resistance to the combined drugs. The Seventh WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, [26] reporting in 1997, concluded that the MB duration of treatment—then standing at 24 months—could safely be shortened to 12 months "without significantly compromising its efficacy."

Persistent obstacles to the elimination of the disease include improving detection, educating patients and the population about its cause, and fighting social taboos about a disease for which patients have historically been considered "unclean" or "cursed by God" as outcasts. Where taboos are strong, patients may be forced to hide their condition (and avoid seeking treatment) to avoid discrimination. The lack of awareness about Hansen's disease can lead people to falsely believe that the disease is highly contagious and incurable.

References

- ↑ Reich CV (1987). "Leprosy: cause, transmission, and a new theory of pathogenesis". Rev. Infect. Dis. 9 (3): 590–4. PMID 3299638.

- ↑ Rojas-Espinosa O, Løvik M (2001). "Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepraemurium infections in domestic and wild animals". Rev. - Off. Int. Epizoot. 20 (1): 219–51. PMID 11288514.

- ↑ Hastings RC, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Franzblau SG (1988). "Leprosy". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1 (3): 330–48. PMID 3058299.

- ↑ Alcaïs A, Mira M, Casanova JL, Schurr E, Abel L (2005). "Genetic dissection of immunity in leprosy". Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17 (1): 44–8. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.006. PMID 15653309.

- ↑ Kaur H, Van Brakel W (2002). "Dehabilitation of leprosy-affected people--a study on leprosy-affected beggars". Leprosy review. 73 (4): 346–55. PMID 12549842.

- ↑ Doull JA, Guinto RA, Rodriguez RS; et al. (1942). "The incidence of leprosy in Cordova and Talisay, Cebu, Philippines". International Journal of Leprosy. 10: 107–131.

- ↑ Noordeen S, Neelan P (1978). "Extended studies on chemoprophylaxis against leprosy". Indian J Med Res. 67: 515–27. PMID 355134.

- ↑ Weddell G, Palmer E (1963). "The pathogenesis of leprosy. An experimental approach". Leprosy Review. 34: 57–61. PMID 13999438.

- ↑ Job C, Jayakumar J, Aschhoff M (1999). ""Large numbers" of Mycobacterium leprae are discharged from the intact skin of lepromatous patients; a preliminary report". Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 67 (2): 164–7. PMID 10472371.

- ↑ Arch Dermato Syphilis 1898; 44:159–174

- ↑ Shepard C (1960). "Acid-fast bacilli in nasal excretions in leprosy, and results of inoculation of mice". Am J Hyg. 71: 147–57. PMID 14445823.

- ↑ Pedley J (1973). "The nasal mucus in leprosy". Lepr Rev. 44 (1): 33–5. PMID 4584261.

- ↑ Davey T, Rees R (1974). "The nasal dicharge in leprosy: clinical and bacteriological aspects". Lepr Rev. 45 (2): 121–34. PMID 4608620.

- ↑ Rees R, McDougall A (1977). "Airborne infection with Mycobacterium leprae in mice". J Med Microbiol. 10 (1): 63–8. PMID 320339.

- ↑ Chehl S, Job C, Hastings R (1985). "Transmission of leprosy in nude mice". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 34 (6): 1161–6. PMID 3914846.

- ↑ "Hansen's Disease (Leprosy)". Technical Information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005-10-12. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ↑ Montestruc E, Berdonneau R (1954). "2 New cases of leprosy in infants in Martinique". Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales (in French). 47 (6): 781–3. PMID 14378912.

- ↑ City of Houston Government Center, Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Hansen's disease (leprosy) Retrieved from http://www.houstontx.gov/health/ComDisease/hansens.html

- ↑ "Probable Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southern United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Armadillos linked to leprosy in humans". CNN. 2011-04-28.

- ↑ Truman, Richard W.; Singh, Pushpendra; Sharma, Rahul; Busso, Philippe; Rougemont, Jacques; Paniz-Mondolfi, Alberto; Kapopoulou, Adamandia; Brisse, Sylvain; Scollard, David M. (2011). "Probable Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southern United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society. 364 (17): 1626–1633. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1010536. PMC 3138484. PMID 21524213. Retrieved 3 May 2011. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "About leprosy: frequently asked questions". American Leprosy Missions, Inc. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ↑ Rees RJ, Pearson JM, Waters MF (1970). "Experimental and clinical studies on rifampicin in treatment of leprosy". Br Med J. 688 (1): 89–92. PMID 4903972.

- ↑ Yawalkar SJ, McDougall AC, Languillon J, Ghosh S, Hajra SK, Opromolla DV, Tonello CJ (1982). "Once-monthly rifampicin plus daily dapsone in initial treatment of lepromatous leprosy". Lancet. 8283 (1): 1199–1202. PMID 6122970.

- ↑ "Chemotherapy of Leprosy". WHO Technical Report Series 847. WHO. 1994. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ "Seventh WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy". WHO Technical Report Series 874. WHO. 1998. Retrieved 2007-03-24.