Oesophagostomum: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{{SI}} | {{SI}} | ||

{{CMG}} | {{CMG}} | ||

{{EH}} | {{EH}} | ||

Revision as of 02:45, 14 January 2009

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;"|Template:Taxobox name | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;" | Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||

| Oesophagostomum bifurcum |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Oesophagostomum |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Oesophagostomum Most cited articles on Oesophagostomum |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Oesophagostomum |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Oesophagostomum at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Oesophagostomum Clinical Trials on Oesophagostomum at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Oesophagostomum NICE Guidance on Oesophagostomum

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Oesophagostomum Discussion groups on Oesophagostomum Patient Handouts on Oesophagostomum Directions to Hospitals Treating Oesophagostomum Risk calculators and risk factors for Oesophagostomum

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Oesophagostomum |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Oesophagostomum bifurcum is a free-living nematode (roundworm). The parasite is a common parasite of the colons of sheep, goats, pigs, cattle, apes, monkeys and other wildlife, in which they may cause serious illness, characterized by emaciation, dysentery and peritonitis. These worms occur in West and East Africa, Brazil, Indonesia, the Philippines, China and less commonly, in central and southern Africa. Because the eggs may be indistinguishable from those of the hookworms (which are widely distributed and can also rarely cause helminthomas), the species causing human helminthomas may not be accurately identified.[1]

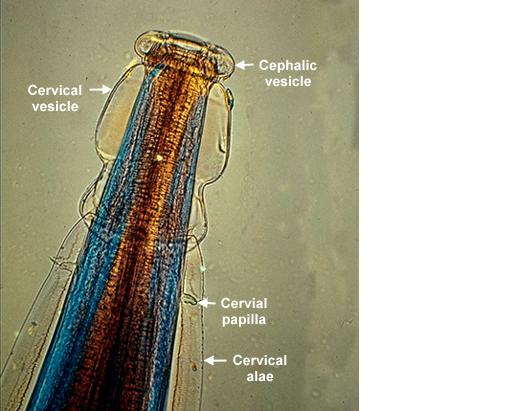

Morphology

A member of the Strongyloids, the morphology of Oesophagostomum bifurcum resembles that of other parasites found in this family. Adults are generally stout and white, with the male being smaller (6-16.6 mm) than the female (6.5-24 mm). The eggs have a thin shell and range in size from 50 and 100 microns. The mouth is surrounded by oral papillae. A cylindrical capsule is surrounded by a protective "external leaf crown" that is called the corona radiata. Similar to other nematodes in this family, Oesophagostomum contains a well-developed, multi-nucleated digestive tract and an immature reproductive system.

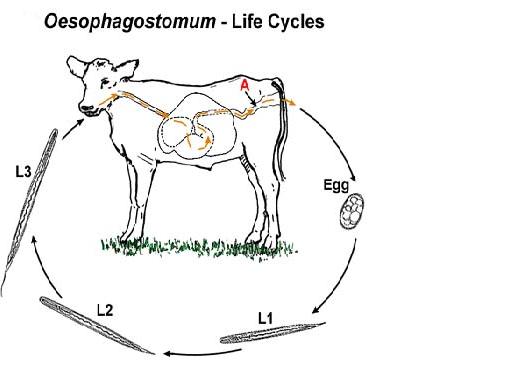

Life Cycle

In the life cycle of Oesophagostomum bifurcum, eggs are passed in the feces of the animal host, such as cattle, sheep, goats, cows, wild pigs, and primates; then the larvae hatch in the soil and develop to their infective stage and are ingested by a new host feeding on contaminated grass (man is an accidental host for this parasite by accidentally ingesting soil that is contaminated with feces). Within their new host, larvae leave their sheaths and penetrate into the wall of the intestine, usually in the lower small bowel, and molt to their third stage. In 5 days they return to the intestinal lumen and move to the cecum and colon, where they undergo another molt and become adults. They may then penetrate the intestinal mucosa again, and the worms provoke an inflammatory reaction in the muscular layer of the bowel. The adults are then passed in the feces of the animal host to the soil, where there may be reinfection of a new host that feeds on the contaminated grass.

Epidemiology

Clinical cases are primarily localized to northern Togo and Ghana in West Africa.

Because the epidemiology of Oesophagostomum bifurcum is clinically relevant to the people living in these areas, many studies have been carried out in order to elucidate the mode of transmission and the reason why the parasite is located in these specific foci. Below is a review of some epidemiological studies on Oesophagostomum bifurcum.

"Human Oesophagostomum infection in northern Togo and Ghana: epidemiological aspects." By: Krepel et al. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology.1992. 86:289-300.

A regional survey of O. bifurcum infection was carried out in Togo and Ghana. The parasite was found in 38 of the 43 villages surveyed, with the highest prevalence rates reaching 59% in some small, isolated villages. Infection was found to be positively correlated with hookworm infection; however, the difficulty in distinguishing these parasites may have had some confounding effect. Infection rates were low in children under 3 years of age, beyond that, rates of infection increased dramatically until 10 years of age. Interestingly, females showed higher prevalence of infection (34%)than men (24%). Based on these epidemiological studies, this group was ale to conclude that tribe, profession, or religion had no effect on the prevalence of infection in the different communities surveyed. The habitats and life cycle of this parasite do not explain its distribution.[2]

"Clinical epidemiology and classification of human oesophagostomiasis." By: P.A. Storey et al. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000. 94:177-182.

The study investigated the clinical epidemiology of oesophagostomiasis by observing 156 cases in the Nalerigu hospital between 1996-1998. About 1 patient/week presented with this disease over the course of two years and 1% of all surgeries carried out were related to oesophagostomiasis. 13% of the patients presented with the multinodular form of the disease in which they had several nodules in their small intestine, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. The other 87% of the patients presented with the Dapaong, or single, tumor form of the disease that was associated with inflammation in the abdomen, fever, and pain.[3]

Clinical Manifestation

Two major types of nodular pathology typically result from Oesophagostomiasis. Some patients develop a multinodular disease in which the colon is studded with many tiny nodules. Other patients present with the Dapaong disease. In this case, only a single nodular mass develops but it can be throughout the colon wall. Nodules are not necessarily a problem unless they cause bowel obstruction or chronic colonic inflammation. Consequently, the Dapaong tumor disease is considered the more severe of the two types because of the pain it causes and the obstruction that occurs.[4]

In some rare cases, serious disease can occur including emaciation, fluid in the pericardium, cardiomegaly, hepatospleenomegaly, perispleenitis, and enlargement of the appendix.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Oesophagostomiasis is confirmed by surgery and identification of the worm as Oesophagostomum spp. Unlike other parasitic diseases, Oesophagostomiasis cannot be diagnosed by eggs in the stool since they are rarely found and when they are found, they cannot be distinguished from hookworm eggs.

Treatment

Treatment with drugs such as albendazole, pyrantel pamoate, levamisole, and thiabendazole can play a critical role in treating people who are infected and had colon nodules but are asymptomatic. If left untreated, people with asymptomatic nodular disease will go on to develop the pathological form of the disease.

References

- ↑ http://tmcr.usuhs.mil/tmcr/chapter18/epidemiology.htm

- ↑ "Human Oesophagostomum infection in northern Togo and Ghana: epidemiological aspects." By: Krepel et al. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology.1992. 86:289-300.

- ↑ "Clinical epidemiology and classification of human oesophagostomiasis." By: P.A. Storey et al. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000. 94:177-182.

- ↑ http://www.stanford.edu/class/humbio103/ParaSites2002/oesophagostomiasis/disease.html