Prostate cancer pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

Shanshan Cen (talk | contribs) |

Shanshan Cen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

* Prostate cancer is classified as an [[adenocarcinoma]], or [[glandular]] cancer. The region of prostate gland where the [[adenocarcinoma]] is most common is the peripheral zone.<ref>{{cite web|title=Prostate Cancer|url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate|website=National Cancer Institute|accessdate=12 October 2014}}</ref> | * Prostate cancer is classified as an [[adenocarcinoma]], or [[glandular]] cancer. The region of prostate gland where the [[adenocarcinoma]] is most common is the peripheral zone.<ref>{{cite web|title=Prostate Cancer|url=http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate|website=National Cancer Institute|accessdate=12 October 2014}}</ref> | ||

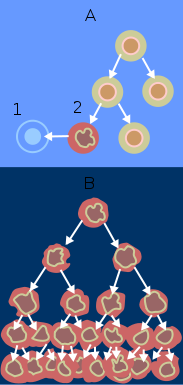

* Initially, small clumps of cancer cells remain confined to otherwise normal prostate glands, a condition known as [[carcinoma in situ]] or [[prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia]] (PIN). | * Initially, small clumps of cancer cells remain confined to otherwise normal prostate glands, a condition known as [[carcinoma in situ]] or [[prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia]] (PIN).<ref name='metastasis-route'>{{cite web | url = http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/path/gu/prostate3.cfm | title = Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms | accessdate = 2011-04-28 | work = Pathology study images | publisher = University of Virginia School of Medicine | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5yHQ19Rrp | archivedate = 2011-04-28 | quote = There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.}}</ref> | ||

* Although there is no proof that PIN is a cancer precursor, it is closely associated with cancer. Over time these cancer cells begin to multiply and spread to the surrounding prostate tissue (the [[stroma]]) forming a [[tumor]]. | * Although there is no proof that PIN is a cancer precursor, it is closely associated with cancer. Over time these cancer cells begin to multiply and spread to the surrounding prostate tissue (the [[stroma]]) forming a [[tumor]].<ref name='metastasis-route'>{{cite web | url = http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/path/gu/prostate3.cfm | title = Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms | accessdate = 2011-04-28 | work = Pathology study images | publisher = University of Virginia School of Medicine | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5yHQ19Rrp | archivedate = 2011-04-28 | quote = There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.}}</ref> | ||

* Eventually, the [[tumor]] may grow large enough to invade nearby [[organs]] such as the [[seminal vesicles]] or the [[rectum]], or the tumor cells may develop the ability to travel in the [[blood stream]] and [[lymphatic system]]. | * Eventually, the [[tumor]] may grow large enough to invade nearby [[organs]] such as the [[seminal vesicles]] or the [[rectum]], or the tumor cells may develop the ability to travel in the [[blood stream]] and [[lymphatic system]].<ref name='metastasis-route'>{{cite web | url = http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/path/gu/prostate3.cfm | title = Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms | accessdate = 2011-04-28 | work = Pathology study images | publisher = University of Virginia School of Medicine | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5yHQ19Rrp | archivedate = 2011-04-28 | quote = There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.}}</ref> | ||

* Prostate cancer is considered a [[malignant]] tumor because it is a [[mass]] of [[cells]] which can invade other parts of the body. This invasion of other organs is called [[metastasis]]. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the [[bone]]s, [[lymph node]]s, [[rectum]], and [[bladder]].<ref name='metastasis-route'>{{cite web | url = http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/path/gu/prostate3.cfm | title = Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms | accessdate = 2011-04-28 | work = Pathology study images | publisher = University of Virginia School of Medicine | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5yHQ19Rrp | archivedate = 2011-04-28 | quote = There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.}}</ref> | * Prostate cancer is considered a [[malignant]] tumor because it is a [[mass]] of [[cells]] which can invade other parts of the body. This invasion of other organs is called [[metastasis]]. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the [[bone]]s, [[lymph node]]s, [[rectum]], and [[bladder]].<ref name='metastasis-route'>{{cite web | url = http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/path/gu/prostate3.cfm | title = Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms | accessdate = 2011-04-28 | work = Pathology study images | publisher = University of Virginia School of Medicine | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5yHQ19Rrp | archivedate = 2011-04-28 | quote = There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:50, 21 September 2015

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

|

Prostate cancer Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Prostate cancer pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Prostate cancer pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Prostate cancer pathophysiology |

Overview

On microscopic histopathological analysis, increased gland density, small circular glands, basal cells lacking, and cytological abnormalities are characteristic findings of prostate cancer.

Pathogenisis

- Prostate cancer is classified as an adenocarcinoma, or glandular cancer. The region of prostate gland where the adenocarcinoma is most common is the peripheral zone.[1]

- Initially, small clumps of cancer cells remain confined to otherwise normal prostate glands, a condition known as carcinoma in situ or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN).[2]

- Although there is no proof that PIN is a cancer precursor, it is closely associated with cancer. Over time these cancer cells begin to multiply and spread to the surrounding prostate tissue (the stroma) forming a tumor.[2]

- Eventually, the tumor may grow large enough to invade nearby organs such as the seminal vesicles or the rectum, or the tumor cells may develop the ability to travel in the blood stream and lymphatic system.[2]

- Prostate cancer is considered a malignant tumor because it is a mass of cells which can invade other parts of the body. This invasion of other organs is called metastasis. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the bones, lymph nodes, rectum, and bladder.[2]

Gross Pathology

Prostate cancer is uncommonly apparent on gross.[3]

Microscopic Pathology

Major criteria:[4]

1.Architecture

- Increased gland density

- Small circular glands

- In rare subtypes - large branching glands

2.Basal cells lacking

3.Cytological abnormalities:

Minor criteria:

- Nuclear hyperchromasia

- Wispy blue mucin

- Pink amorphous secretions

- Intraluminal crystalloid

- Amphophilic cytoplasm

- Adjacent High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN)

- Mitoses - quite rare

Prostate adenocarcinoma: Microscopic View

{{#ev:youtube|1SZPLS1dxTo}}

Gleason score

- See Gleason score

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 1)

{{#ev:youtube|F7V0Zl7a2FY}}

Prostate : Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 2)

{{#ev:youtube|YSOLiSklIXw}}

Prostate : Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 3)

{{#ev:youtube|TG8vR_pE7yA}}

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 4)

{{#ev:youtube|R2Cl4HScdGc}}

Prostate: Adenocarcinoma (Gleason grade 5)

{{#ev:youtube|F7V0Zl7a2FY}}

References

- ↑ "Prostate Cancer". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Male Genitals - Prostate Neoplasms". Pathology study images. University of Virginia School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2011-04-28. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

There are many connections between the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral veins. The veins forming the prostatic plexus do not contain valves and it is thought that straining to urinate causes prostatic venous blood to flow in a reverse direction and enter the vertebral veins carrying malignant cells to the vertebral column.

- ↑ Prostatic carcinoma.Dr Ian Bickle and Dr Saqba Farooq et al. Radiopaedia.org 2015.http://radiopaedia.org/articles/prostatic-carcinoma-1

- ↑ Humphrey PA (2007). "Diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in prostate needle biopsy tissue". J. Clin. Pathol. 60 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.036442. PMC 1860598. PMID 17213347. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)