Surgical staple

Surgical staples are specialized staples used in surgery in place of sutures to close skin wounds, anastomoses bowel or portions of lung. A more recent development, from the 1990s, uses clips instead of staples for some applications; this does not require the staple to penetrate.

Stapling is much faster than suturing by hand, and also more accurate and consistent. In bowel and lung surgery, staples are primarily used because staple lines are less likely to leak blood, air or bowel contents. In skin closure, dermal adhesives (skin glues) are also an increasingly common alternative.

The technique of stapling for surgery is said to have been influenced by the Roman use of ants for wound closure.

History

Staplers were originally developed to address the perceived problem of patency (security against leaks of blood or bowel contents) in anastomoses in particular. Leaks from poor suturing of bowel anastomoses was at that time a significant cause of post-surgical mortality. More recent studies have shown that with current suturing techniques there is no significant difference in outcome between hand sutured and mechanical anastomoses, but mechanical anastomoses are significantly quicker to perform.[1]

The technique was pioneered by a Hungarian surgeon, Humer Hultl,[2] known as the "father of surgical stapling".[3] Hultl's prototype stapler of 1908 weighed eight pounds (3.6kg), and required two hours to assemble and load. Many hours were spent trying to achieve a consistent staple line and reliably patent anastomoses.

The early instruments, by developers including Hultl, von Petz, Friedrich and Nakayama, were complex and cumbersome to use, but were refined over time. Experiments were informally reported abroad, and in 1964 entrepreneur Leon C. Hirsch founded the United States Surgical Corporation to manufacture surgical staplers under its Auto Suture brand.[4] Until the late 1970s USSC had the market essentially to itself, but in 1977 Johnson & Johnson's Ethicon brand entered the market and today both are widely used, along with competitors from the Far East. USSC was bought by Tyco Healthcare in 1998.

Safety and patency of mechanical (stapled) bowel anastomoses has been widely studied. It is generally the case in such studies that sutured anastomoses are either comparable or less prone to leakage.[5] It is possible that this is the result of recent advances in suture technology, along with increasingly risk-conscious surgical practice. Certainly modern synthetic sutures are more predictable and less prone to infection than catgut, silk and linen, which were the main suture materials used up to the 1990s.

One key feature of intestinal staplers is that the edges of the stapler act as a haemostat, compressing the edges of the wound and closing blood vessels during the stapling process.

Types and applications

The first commercial staplers were made of stainless steel with titanium staples loaded into reloadable staple cartridges.

Modern surgical staplers are either disposable, made of plastic, or reusable, made of stainless steel. Both types are generally loaded using disposable cartridges.

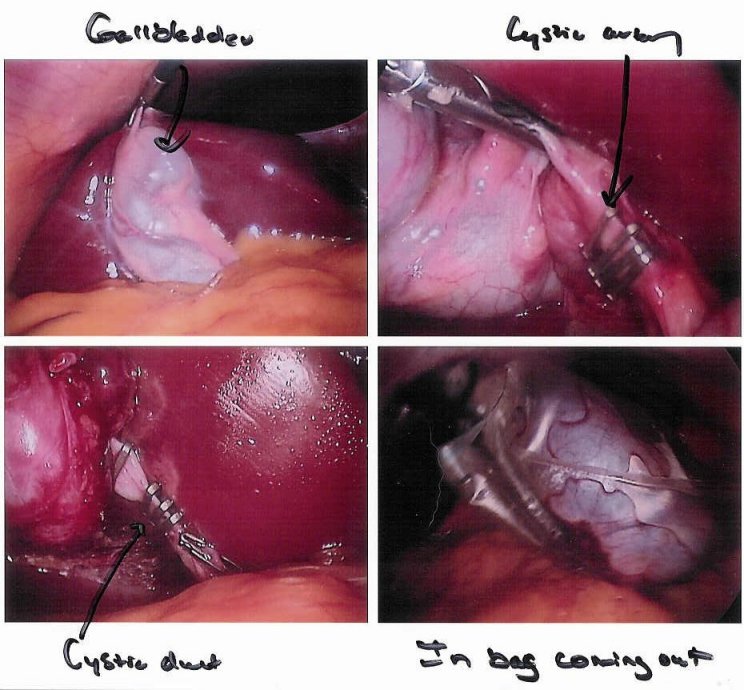

The staple line may be straight, curved or circular. Circular staplers are used for end-to-end anastomosis after bowel resection or, somewhat more controversially, in esophagogastric surgery.[6] The instruments may be used in either open or laparoscopic surgery, different instruments are used for each application. Laparoscopic staplers are longer, thinner, and may be articulated to allow for access from a restricted number of trocar ports.

Some staplers incorporate a knife, to complete excision and anastomosis in a single operation.

Staplers are used to close both internal and skin wounds. Skin staples are usually applied using a disposable stapler, and removed with a specialized staple remover. Staplers are also used in vertical banded gastroplasty surgery (popularly known as "stomach stapling").

Although most surgical staples are made of titanium, stainless steel is more often used in some skin staples and clips. Titanium produces less reaction with the immune system and, being non-ferrous, does not interfere significantly with MRI scanners, although some imaging artifacts may result. Synthetic absorbable (bioabsorbable) staples are also now becoming available, based on polyglycolic acid, as with many synthetic absorbable sutures.

See also

References

- ↑ Suregery Today, Volume 34, Number 2 / February, 2004

- ↑ Non-suture methods of vascular anastomosis, British Journal of Surgery, 19 Feb 2003: Volume 90, Issue 3, Pages 261 - 271

- ↑ Circular vascular stapling in coronary surgery, Konstantinov, Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 2004; 78: 369-373

- ↑ History of United States Surgical Corporation

- ↑ e.g. Stapled versus Sutured Gastrointestinal Anastomoses in the Trauma Patient: A Multicenter Trial, Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care. 51(6):1054-1061, December 2001.

- ↑ European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 25, Issue 6, June 2004, Pages 1097-1101