Influenza historical perspective

|

Influenza Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Influenza historical perspective On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Influenza historical perspective |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Influenza historical perspective |

For more information about non-human (variant) influenza viruses that may be transmitted to humans, see Zoonotic influenza

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Alejandro Lemor, M.D. [2]

Overview

Influenza-like symptoms have been reported for thousands of years, but the first pandemic outbreak recorded in Asia, Europe and Africa was in 1580. Since then, several outbreaks have been reported, including the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 that killed 50 to 100 million patients, the Asian flu pandemic of 1957, and the Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968. The first vaccine against influenza was developed in the 1940s to prevent outbreaks within the US military during World War II.

Historical Perspective

- The symptoms of human influenza were clearly described by Hippocrates roughly 2400 years ago.[1][2]

- Since then, the virus has caused numerous pandemics.

- Historical data on influenza are difficult to interpret, because the symptoms can be similar to those of other diseases, such as diphtheria, pneumonic plague, typhoid fever, dengue, or typhus.

- The first convincing record of an influenza pandemic was of an outbreak in 1580, which began in Asia and spread to Europe via Africa.

- In Rome over 8,000 people were killed, and several Spanish cities were almost wiped out.

- Pandemics continued sporadically throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, with the pandemic of 1830–1833 being particularly widespread; it infected approximately a quarter of the people exposed.[3]

|

Spanish Flu Pandemic

- The most famous and lethal outbreak was the so-called Spanish flu pandemic (type A influenza, H1N1 subtype), which lasted from 1918 to 1919.

- Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people[5] while current estimates say 50 million to 100 million people worldwide were killed.[6]

- This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed as many people as the Black Death.[3]

- This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.[5]

- Indeed, symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid.

- The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[4]

- The Spanish flu pandemic was truly global, spreading even to the Arctic and remote Pacific islands.

- The unusually severe disease killed between 2 and 20% of those infected, as opposed to the more usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%.[4][6]

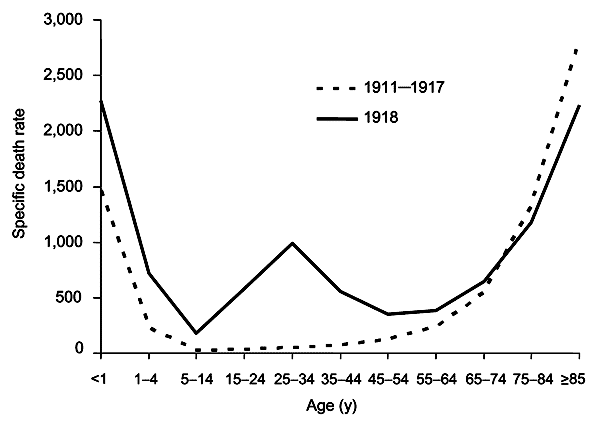

- Another unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.[7]

- This is unusual since influenza is normally most deadly to the very young (under age 2) and the very old (over age 70).

- The total mortality of the 1918–1919 pandemic is not known, but it is estimated that 2.5% to 5% of the world's population was killed. As many as 25 million may have been killed in the first 25 weeks; in contrast, HIV/AIDS has killed 25 million in its first 25 years.[6]

| Name of pandemic | Date | Deaths | Case fatality rate | Subtype involved | Pandemic Severity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889–1890 Flu Pandemic (Asiatic or Russian Flu)[10] |

1889–1890 | 1 million | 0.15% | possibly H3N8 or H2N2 |

N/A |

| 1918 Flu Pandemic (Spanish flu)[11] |

1918–1920 | 20 to 100 million | 2% | H1N1 | 5 |

| Asian Flu | 1957–1958 | 1 to 1.5 million | 0.13% | H2N2 | 2 |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968–1969 | 0.75 to 1 million | <0.1% | H3N2 | 2 |

| Russian flu | 1977–1978 | no accurate count | N/A | H1N1 | N/A |

| 2009 Flu Pandemic[12] | 2009–2010 | 105,700-395,600[13] | 0.03% | H1N1 | N/A |

Other Flu Pandemics

- Later flu pandemics were not so devastating.

- They included the following:

- The 1957 Asian Flu (type A, H2N2 strain)

- The 1968 Hong Kong Flu (type A, H3N2 strain)

- Even these smaller outbreaks killed millions of people.

- In later pandemics antibiotics were available to control secondary infections and this may have helped reduce mortality compared to the Spanish Flu of 1918.[4]

- Although there were scares in New Jersey in 1976 (with the Swine Flu), world wide in 1977 (with the Russian Flu), and in Hong Kong and other Asian countries in 1997 (with H5N1 avian influenza), there have been no major pandemics since the 1968 Hong Kong Flu.

- Immunity to previous pandemic influenza strains and vaccination may have limited the spread of the virus and may have helped prevent further pandemics.[8]

Influenza Virus

- The etiology of influenza, the Orthomyxoviridae family of viruses, was first discovered in pigs by Richard Schope in 1931.[14]

- This discovery was shortly followed by the isolation of the virus from humans by a group headed by Patrick Laidlaw at the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom in 1933.[15]

- However, it was not until Wendell Stanley first crystallized tobacco mosaic virus in 1935 that the non-cellular nature of viruses was appreciated.

Flu Vaccine

- The first significant step towards preventing influenza was the development in 1944 of a killed-virus vaccine for influenza by Thomas Francis, Jr.

- This built on work by Frank Macfarlane Burnet, who showed that the virus lost virulence when it was cultured in fertilized hen's eggs.[16]

- Application of this observation by Francis allowed his group of researchers at the University of Michigan to develop the first flu vaccine, with support from the U.S. Army.[17]

- The Army was deeply involved in this research due to its experience of influenza in World War I, when thousands of troops were killed by the virus in a matter of months.[6]

Past Flu Seasons Adapted from CDC [18]

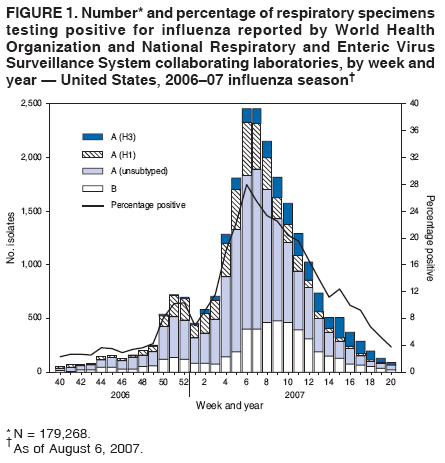

2006-2007

- During October 1, 2006--May 19, 2007, the WHO and the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 179,268 respiratory specimens for influenza viruses; 23,753 (13.2%) were positive.

- Of these, 18,817 (79.2%) were influenza A viruses and 4,936 (20.8%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the influenza A viruses, 6,280 (33.4%) were subtyped; 3,912 (62.3%) were influenza A (H1) viruses and 2,368 (37.7%) were influenza A (H3) viruses.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza first exceeded 10% during the week ending December 23, 2006 (week 51), peaked at 28.0% during the week ending February 10, 2007 (week 6), and declined to less than 10% during the week ending April 28, 2007 (week 17).

- The proportion was above 10% positive for 14 consecutive weeks.

- The peak percentage of specimens testing positive for influenza during the previous three seasons ranged from 22.6% to 34.7%, and the peak occurred during early December to early March.

- During the previous three influenza seasons, the number of consecutive weeks during which more than 10% of specimens tested positive for influenza ranged from 13 to 17 weeks.

2007-2008

- During September 30, 2007--May 17, 2008, the WHO and the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 225,329 specimens for influenza viruses; 39,827 (18%) were positive.

- Of the positive specimens, 28,263 (71%) were influenza A viruses, and 11,564 (29%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the influenza A viruses, 8,290 (29%) were subtyped; 2,175 (26%) were influenza A (H1N1), and 6,115 (74%) were influenza A (H3N2) viruses.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza first exceeded 10% during the week ending January 12, 2008 (week 2), peaked at 32% during the week ending February 9, 2008 (week 6), and declined to <10% during the week ending April 19, 2008 (week 16).

- The proportion positive was above 10% for 14 consecutive weeks.

- The peak percentage of specimens testing positive for influenza during the previous three seasons ranged from 22% to 34% and the peak occurred during mid-February to early March.

- During the previous three influenza seasons, the number of consecutive weeks during which more than 10% of specimens tested positive for influenza ranged from 13 to 17 weeks

2008-2009

- From September 28, 2008, to April 4, 2009, the (WHO) and the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 173,397 respiratory specimens for influenza viruses, 24,793 (14.3%) of which were positive.

- Of these, 16,686 (67.3%) were positive for influenza A viruses, and 8,107 (32.7%) were positive for influenza B viruses.

- Of the 16,686 specimens positive for influenza A viruses, 6,735 (40.4%) were subtyped by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction or by virus culture; 6,049 (89.8%) of these were influenza A (H1N1) viruses, and 686 (10.2%) were influenza A (H3N2) viruses.

- The percentage of specimens testing positive for influenza first exceeded the seasonal threshold of 10% during the week ending January 17, 2009, and peaked at 25.0% during the week ending February 14, 2009.

- For the week ending April 4, 2009, 12.3% of specimens tested for influenza were positive.

- The relative proportion of influenza B viruses increased during February and March, and since the week ending March 14, 2009, >50% of the positive influenza specimens have been influenza B.

2009-2010

- Since April 2009, the beginning of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, through June 12, 2010, approximately 740,000 influenza specimens were tested for influenza, and the number of laboratory-confirmed positives was approximately four times the average of the previous four seasons.

- Two peaks in percentage of specimens testing positive for influenza occurred: 43.1% in June during the initial pandemic wave, and 38.2% in October during the second wave.

- During August 30, 2009--June 12, 2010, the 2009--10 influenza season, the WHO and National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 468,218 specimens for influenza viruses; 91,152 (19.5%) were positive.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza during the 2009--10 season exceeded 20% during the week ending August 30, 2009, peaked at 38.2% during the week ending October 24, and declined to less than 10% during the week ending December 12.

- Of the 91,152 positive specimens from 2009-10 season, 90,758 (99.6%) were influenza A viruses and 394 (0.4%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the influenza A viruses, 67,022 (73.8%) were subtyped; 66,916 (99.8%) were 2009 pandemic H1N1, 72 (0.1%) were influenza A (H3N2), and 34 (0.1%) were seasonal influenza A (H1N1) viruses.

2010-2011

- During October 3, 2010--May 21, 2011, the WHO and National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 246,128 specimens for influenza viruses; 54,226 (22%) were positive.

- Of the positive specimens, 40,282 (74%) were influenza A viruses, and 13,944 (26%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the influenza A viruses, 28,545 (71%) were subtyped; 17,599(62%) were influenza A (H3N2) viruses, and 10,946 (38%) were 2009 influenza A (H1N1) viruses.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza during the 2010-11 season first exceeded 10%, indicating higher levels of virus circulation, during the week ending November 27, 2010.

- The proportion peaked at 36% during the week ending February 5, 2011, and declined to <10% during the week ending April 16, 2011.

2011-2012

- During October 2, 2011–May 19, 2012, the WHO) and National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 169,453 specimens for influenza viruses; 22,417 (13%) were positive.

- Of the positive specimens, 19,285 (86%) were influenza A viruses, and 3,132 (14%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the influenza A viruses, 14,968 (78%) were subtyped; 11,002 (74%) were influenza A (H3N2) viruses, and 3,966 (26%) were pH1N1 viruses.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza during the 2011–12 season first exceeded 10% (indicating higher levels of viral circulation) during the week ending February 4, 2012, and peaked at 32% during the week ending March 17, 2012.

2012-2013

- During September 30, 2012–May 18, 2013, the WHO and National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System collaborating laboratories in the United States tested 311,333 specimens for influenza viruses; 73,130 (23%) were positive.

- Of the positive specimens, 51,675 (71%) were influenza A viruses, and 21,455 (29%) were influenza B viruses.

- Among the seasonal influenza A viruses, 34,922 (68%) were subtyped; 33,423 (96%) were influenza A (H3N2) viruses, and 1,497 (4%) were pH1N1 viruses.

- In addition, two variant influenza A (H3N2v) viruses were identified.

- Typically the influenza season is said to begin when certain key indicators remain elevated for a number of consecutive weeks.

- One of these indicators is the percent of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza.

- The proportion of specimens testing positive for influenza during the 2012–13 season first exceeded 10% during the week ending November 10, 2012 (week 45), and peaked at 38% during the week ending December 29, 2012 (week 52).

References

- ↑ Martin, P (2006). "2,500-year evolution of the term epidemic". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (6). PMID 16707055. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hippocrates (400 BCE). "Of the Epidemics". Retrieved 2006-10-18. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Potter, CW (2006). "A History of Influenza". J Appl Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–579. PMID 11576290. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3

Taubenberger, J (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. PMID 16494711. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Patterson, KD (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (ed.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Simonsen, L (1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". J Infect Dis. 178 (1): 53–60. PMID 9652423. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hilleman, M (19 August 2002). "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control". Vaccine. 20 (25–26): 3068–87. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2. PMID 12163258.

- ↑ "Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza". World Health Organization. 14 October 2005. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ↑ Valleron AJ, Cori A, Valtat S, Meurisse S, Carrat F, Boëlle PY (May 2010). "Transmissibility and geographic spread of the 1889 influenza pandemic". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (19): 8778–81. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8778V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000886107. PMC 2889325. PMID 20421481.

- ↑ Mills CE, Robins JM, Lipsitch M (December 2004). "Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza". Nature. 432 (7019): 904–6. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..904M. doi:10.1038/nature03063. PMID 15602562.

- ↑ Donaldson LJ; Rutter PD; Ellis BM; et al. (2009). "Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study". BMJ. 339: b5213. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5213. PMC 2791802. PMID 20007665. Unknown parameter

|author-separator=ignored (help) - ↑ Dawood, Fatimah S (26 June 2012). "Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: a modelling study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (9): 687–95. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4. PMID 22738893. Retrieved 19 March 2014. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Shimizu, K (1997). "History of influenza epidemics and discovery of influenza virus". Nippon Rinsho. 55 (10): 2505–201. PMID 9360364. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Smith, W (1933). "A virus obtained from influenza patients". Lancet. 2: 66–68. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet: Biography The Nobel Foundation. Accessed 22 Oct 06

- ↑ Kendall, H (2006). "Vaccine Innovation: Lessons from World War II" (PDF). Journal of Public Health Policy. 27 (1): 38–57.

- ↑ "CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) - Influenza Activity".