Human genome project

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

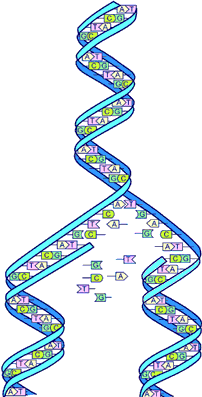

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with a primary goal to determine the sequence of chemical base pairs which make up DNA and to identify the approximately 25,000 genes of the human genome from both a physical and functional standpoint.

The project began in 1990 initially headed by James D. Watson at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. A working draft of the genome was released in 2000 and a complete one in 2003, with further analysis still being published. A parallel project was conducted by the private company Celera Genomics. Most of the sequencing was performed in universities and research centers from the United States, Canada and Great Britain. The mapping of human genes is an important step in the development of medicines and other aspects of health care.

While the objective of the Human Genome Project is to understand the genetic makeup of the human species, the project also has focused on several other nonhuman organisms such as E. coli, the fruit fly, and the laboratory mouse. It remains one of the largest single investigational projects in modern science.

The HGP originally aimed to map the nucleotides contained in a haploid reference human genome (more than three billion). Several groups have announced efforts to extend this to diploid human genomes including the International HapMap Project, Applied Biosystems, Perlegen, Illumina, JCVI, Personal Genome Project, and Roche-454.

The "genome" of any given individual (except for identical twins and cloned animals) is unique; mapping "the human genome" involves sequencing multiple variations of each gene. The project did not study the entire DNA found in human cells; some heterochromatic areas (about 8% of the total) remain un-sequenced.

The Project

Background

Initiation of the Project was the culmination of several years of work supported by the United States Department of Energy, in particular workshops in 1984 [1] and 1986 and a subsequent initiative the US Department of Energy.[2] This 1986 report stated boldly, "The ultimate goal of this initiative is to understand the human genome" and "knowledge of the human genome is as necessary to the continuing progress of medicine and other health sciences as knowledge of human anatomy has been for the present state of medicine." Candidate technologies were already being considered for the proposed undertaking at least as early as 1985.[3]

James D. Watson was head of the National Center for Human Genome Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States starting from 1988. Largely due to his disagreement with his boss, Bernadine Healy, over the issue of patenting genes, he was forced to resign in 1992. He was replaced by Francis Collins in April 1993, and the name of the Center was changed to the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) in 1997.

The $3-billion project was formally founded in 1990 by the United States Department of Energy and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and was expected to take 15 years. In addition to the United States, the international consortium comprised geneticists in China, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Due to widespread international cooperation and advances in the field of genomics (especially in sequence analysis), as well as major advances in computing technology, a 'rough draft' of the genome was finished in 2000 (announced jointly by then US president Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair on June 26, 2000).[4] Ongoing sequencing led to the announcement of the essentially complete genome in April 2003, 2 years earlier than planned.[5] In May 2006, another milestone was passed on the way to completion of the project, when the sequence of the last chromosome was published in the journal Nature.[6]

State of completion

There are multiple definitions of the "complete sequence of the human genome". According to some of these definitions, the genome has already been completely sequenced, and according to other definitions, the genome has yet to be completely sequenced. There have been multiple popular press articles reporting that the genome was "complete." The genome has been completely sequenced using the definition employed by the International Human Genome Project. A graphical history of the human genome project shows that most of the human genome was complete by the end of 2003. However, there are a number of regions of the human genome that can be considered unfinished:

- First, the central regions of each chromosome, known as centromeres, are highly repetitive DNA sequences that are difficult to sequence using current technology. The centromeres are millions (possibly tens of millions) of base pairs long, and for the most part these are entirely un-sequenced.

- Second, the ends of the chromosomes, called telomeres, are also highly repetitive, and for most of the 46 chromosome ends these too are incomplete. It is not known precisely how much sequence remains before the telomeres of each chromosome are reached, but as with the centromeres, current technological restraints are prohibitive.

- Third, there are several loci in each individual's genome that contain members of multigene families that are difficult to disentangle with shotgun sequencing methods - these multigene families often encode proteins important for immune functions.

- Other than these regions, there remain a few dozen gaps scattered around the genome, some of them rather large, but there is hope that all these will be closed in the next couple of years.

In summary: the best estimates of total genome size indicate that about 92% of the genome has been completed and it is likely that the centromeres and telomeres will remain un-sequenced until new technology is developed that facilitates their sequencing. Most of the remaining DNA is highly repetitive and unlikely to contain genes, but it cannot be truly known until it is entirely sequenced. Understanding the functions of all the genes and their regulation is far from complete. The roles of junk DNA, the evolution of the genome, the differences between individuals, and many other questions are still the subject of intense interest by laboratories all over the world.

Goals

The goals of the original HGP were not only to determine more than three billion base pairs in the human genome, but also to identify all the genes in this vast amount of data. This part of the project is still ongoing, although a preliminary count indicates about 22,000–23,000 genes in the human genome, which is fewer than predicted by many scientists.

The sequence of the human DNA is stored in databases available to anyone on the Internet. The U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (and sister organizations in Europe and Japan) house the gene sequence in a database known as Genbank, along with sequences of known and hypothetical genes and proteins. Other organizations such as the University of California, Santa Cruz[2], and Ensembl[3] present additional data and annotation and powerful tools for visualizing and searching it. Computer programs have been developed to analyze the data, because the data themselves are difficult to interpret without such programs.

The process of identifying the boundaries between genes and other features in raw DNA sequence is called genome annotation and is the domain of bioinformatics. While expert biologists make the best annotators, their work proceeds slowly, and computer programs are increasingly used to meet the high-throughput demands of genome sequencing projects. The best current technologies for annotation make use of statistical models that take advantage of parallels between DNA sequences and human language, using concepts from computer science such as formal grammars.

Another, often overlooked, goal of the HGP is the study of its ethical, legal, and social implications. It is important to research these issues and find the most appropriate solutions before they become large dilemmas whose effect will manifest in the form of major political concerns.

All humans have unique gene sequences. Therefore the data published by the HGP does not represent the exact sequence of each and every individual's genome. It is the combined genome of a small number of anonymous donors. The HGP genome is a scaffold for future work in identifying differences among individuals. Most of the current effort in identifying differences among individuals involves single nucleotide polymorphisms and the HapMap.

How it was accomplished

Funding came from the US government through the National Institutes of Health in the United States, and the UK charity, the Wellcome Trust, who funded the Sanger Institute (then the Sanger Centre) in Great Britain, as well as numerous other groups from around the world. The genome was broken into smaller pieces; approximately 150,000 base pairs in length. These pieces were then spliced into a type of vector known as "bacterial artificial chromosomes", or BACs, which are derived from bacterial chromosomes which have been genetically engineered. The vectors containing the genes can be inserted into bacteria where they are copied by the bacterial DNA replication machinery. Each of these pieces was then sequenced separately as a small "shotgun" project and then assembled. The larger, 150,000 base pairs go together to create chromosomes. This is known as the "hierarchical shotgun" approach, because the genome is first broken into relatively large chunks, which are then mapped to chromosomes before being selected for sequencing.

The public vs private approaches

In 1998, a similar, privately funded quest was launched by the American researcher Craig Venter, and his firm Celera Genomics. Venter was a scientist at the NIH during the early 1990's when the project was initiated. The $300 million Celera effort was intended to proceed at a faster pace and at a fraction of the cost of the roughly $3 billion publicly funded project.

Celera used a riskier technique called whole genome shotgun sequencing, which had been used to sequence bacterial genomes of up to six million base pairs in length, but not for anything nearly as large as the three billion base pair human genome.

Celera initially announced that it would seek patent protection on "only 200-300" genes, but later amended this to seeking "intellectual property protection" on "fully-characterized important structures" amounting to 100-300 targets. The firm eventually filed preliminary ("place-holder") patent applications on 6,500 whole or partial genes. Celera also promised to publish their findings in accordance with the terms of the 1996 "Bermuda Statement," by releasing new data quarterly (the HGP released its new data daily), although, unlike the publicly funded project, they would not permit free redistribution or commercial use of the data.

In March 2000, President Clinton announced that the genome sequence could not be patented, and should be made freely available to all researchers. The statement sent Celera's stock plummeting and dragged down the biotechnology-heavy Nasdaq. The biotechnology sector lost about $50 billion in market capitalization in two days.

Although the working draft was announced in June 2000, it was not until February 2001 that Celera and the HGP scientists published details of their drafts. Special issues of Nature (which published the publicly funded project's scientific paper)[7] and Science (which published Celera's paper[8]) described the methods used to produce the draft sequence and offered analysis of the sequence. These drafts covered about 83% of the genome (90% of the euchromatic regions with 150,000 gaps and the order and orientation of many segments not yet established). In February 2001, at the time of the joint publications, press releases announced that the project had been completed by both groups. Improved drafts were announced in 2003 and 2005, filling in to ~92% of the sequence currently.

The competition proved to be very good for the project, spurring the public groups to modify their strategy in order to accelerate progress. The rivals initially agreed to pool their data, but the agreement fell apart when Celera refused to deposit its data in the unrestricted public database GenBank. Celera had incorporated the public data into their genome, but forbade the public effort to use Celera data.

HGP is the most well known of many international genome projects aimed at sequencing the DNA of a specific organism. While the human DNA sequence offers the most tangible benefits, important developments in biology and medicine are predicted as a result of the sequencing of model organisms, including mice, fruit flies, zebrafish, yeast, nematodes, plants, and many microbial organisms and parasites.

In 2004, researchers from the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC) of the HGP announced a new estimate of 20,000 to 25,000 genes in the human genome.[9] Previously 30,000 to 40,000 had been predicted, while estimates at the start of the project reached up to as high as 2,000,000. The number continues to fluctuate and it is now expected that it will take many years to agree on a precise value for the number of genes in the human genome.

History

In 1976, the genome of the virus Bacteriophage MS2 was the first complete genome to be determined, by Walter Fiers and his team at the University of Ghent (Ghent, Belgium).[10] The idea for the shotgun technique came from the use of an algorithm that combined sequence information from many small fragments of DNA to reconstruct a genome. This technique was pioneered by Frederick Sanger to sequence the genome of the Phage Φ-X174, a tiny virus called a bacteriophage that was the first fully sequenced genome (DNA-sequence) in 1977.[11] The technique was called shotgun sequencing because the genome was broken into millions of pieces as if it had been blasted with a shotgun. In order to scale up the method, both the sequencing and genome assembly had to be automated, as they were in the 1980s.

Those techniques were shown applicable to sequencing of the first free-living bacterial genome (1.8 million base pairs) of Haemophilus influenzae in 1995 [12] and the first animal genome (~100 Mbp) [13] It involved the use of automated sequencers, longer individual sequences using approximately 500 base pairs at that time. Paired sequences separated by a fixed distance of around 2000 base pairs which were critical elements enabling the development of the first genome assembly programs for reconstruction of large regions of genomes (aka 'contigs').

Three years later, in 1998, the announcement by the newly-formed Celera Genomics that it would scale up the shotgun sequencing method to the human genome was greeted with skepticism in some circles. The shotgun technique breaks the DNA into fragments of various sizes, ranging from 2,000 to 300,000 base pairs in length, forming what is called a DNA "library". Using an automated DNA sequencer the DNA is read in 800bp lengths from both ends of each fragment. Using a complex genome assembly algorithm and a supercomputer, the pieces are combined and the genome can be reconstructed from the millions of short, 800 base pair ....fragments. The success of both the public and privately funded effort hinged upon a new, more highly automated capillary DNA sequencing machine, called the Applied Biosystems 3700, that ran the DNA sequences through an extremely fine capillary tube rather than a flat gel. Even more critical was the development of a new, larger-scale genome assembly program, which could handle the 30-50 million sequences that would be required to sequence the entire human genome with this method. At the time, such a program did not exist. One of the first major projects at Celera Genomics was the development of this assembler, which was written in parallel with the construction of a large, highly automated genome sequencing factory. Development of the assembler was led by Brian Ramos. The first version of this assembler was demonstrated in 2000, when the Celera team joined forces with Professor Gerald Rubin to sequence the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster using the whole-genome shotgun method[14]. At 130 million base pairs, it was at least 10 times larger than any genome previously shotgun assembled. One year later, the Celera team published their assembly of the three billion base pair human genome.

How it was accomplished

The IHGSC used pair-end sequencing plus whole-genome shotgun mapping of large (~100 Kbp) plasmid clones and shotgun sequencing of smaller plasmid sub-clones plus a variety of other mapping data to orient and check the assembly of each human chromosome[7].

The Celera group emphasized the importance of the “whole-genome shotgun” sequencing method, relying on sequence information to orient and locate their fragments within the chromosome. However they used the publicly available data from HGP to assist in the assembly and orientation process, raising concerns that the Celera sequence was not independently derived.[8] [15][16].

Whose genome was sequenced?

In the IHGSC international public-sector Human Genome Project (HGP), researchers collected blood (female) or sperm (male) samples from a large number of donors. Only a few of many collected samples were processed as DNA resources. Thus the donor identities were protected so neither donors nor scientists could know whose DNA was sequenced. DNA clones from many different libraries were used in the overall project, with most of those libraries being created by Dr. Pieter J. de Jong. It has been informally reported, and is well known in the genomics community, that much of the DNA for the public HGP came from a single anonymous male donor from Buffalo, New York (code name RP11).[17]

HGP scientists used white blood cells from the blood of two male and two female donors (randomly selected from 20 of each) -- each donor yielding a separate DNA library. One of these libraries (RP11) was used considerably more than others, due to quality considerations. One minor technical issue is that male samples contain only half as much DNA from the X and Y chromosomes as from the other 22 chromosomes (the autosomes); this happens because each male cell contains only one X and one Y chromosome, not two like other chromosomes (autosomes).

Although the main sequencing phase of the HGP has been completed, studies of DNA variation continue in the International HapMap Project, whose goal is to identify patterns of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) groups (called haplotypes, or “haps”). The DNA samples for the HapMap came from a total of 270 individuals: Yoruba people in Ibadan, Nigeria; Japanese people in Tokyo; Han Chinese in Beijing; and the French Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisms Humain (CEPH) resource, which consisted of residents of the United States having ancestry from Western and Northern Europe.

In the Celera Genomics private-sector project, DNA from five different individuals were used for sequencing. The lead scientist of Celera Genomics at that time, Craig Venter, later acknowledged (in a public letter to the journal Science) that his DNA was one of those in the pool[18].

On September 4th, 2007, a team led by Craig Venter, published his complete DNA sequence[19], unveiling the six-billion-letter genome of a single individual for the first time.

Benefits

The work on interpretation of genome data is still in its initial stages. It is anticipated that detailed knowledge of the human genome will provide new avenues for advances in medicine and biotechnology. Clear practical results of the project emerged even before the work was finished. For example, a number of companies, such as Myriad Genetics started offering easy ways to administer genetic tests that can show predisposition to a variety of illnesses, including breast cancer, disorders of hemostasis, cystic fibrosis, liver diseases and many others. Also, the etiologies for cancers, Alzheimer's disease and other areas of clinical interest are considered likely to benefit from genome information and possibly may lead in the long term to significant advances in their management.

There are also many tangible benefits for biological scientists. For example, a researcher investigating a certain form of cancer may have narrowed down his/her search to a particular gene. By visiting the human genome database on the world wide web, this researcher can examine what other scientists have written about this gene, including (potentially) the three-dimensional structure of its product, its function(s), its evolutionary relationships to other human genes, or to genes in mice or yeast or fruit flies, possible detrimental mutations, interactions with other genes, body tissues in which this gene is activated, diseases associated with this gene or other datatypes.

Further, deeper understanding of the disease processes at the level of molecular biology may determine new therapeutic procedures. Given the established importance of DNA in molecular biology and its central role in determining the fundamental operation of cellular processes, it is likely that expanded knowledge in this area will facilitate medical advances in numerous areas of clinical interest that may not have been possible without them.

The analysis of similarities between DNA sequences from different organisms is also opening new avenues in the study of the theory of evolution. In many cases, evolutionary questions can now be framed in terms of molecular biology; indeed, many major evolutionary milestones (the emergence of the ribosome and organelles, the development of embryos with body plans, the vertebrate immune system) can be related to the molecular level. Many questions about the similarities and differences between humans and our closest relatives (the primates, and indeed the other mammals) are expected to be illuminated by the data from this project.

The Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP), spinoff research aimed at mapping the DNA that varies between human ethnic groups, which was rumored to have been halted, actually did continue and to date has yielded new conclusions. In the future, HGDP could possibly expose new data in disease surveillance, human development and anthropology. HGDP could unlock secrets behind and create new strategies for managing the vulnerability of ethnic groups to certain diseases (see race in biomedicine). It could also show how human populations have adapted to these vulnerabilities.

See also

- Chimpanzee Genome Project

- Neanderthal Genome Project

- EuroPhysiome

- Gene patent

- Genographic Project

- Genome project

- Human Cytome Project

- Human microbiome project

- Human Variome Project

- International HapMap Project

- National Human Genome Research Institute

- Personal Genome Project

- Sanger Institute

- Craig Venter's Genome

- HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee

- The 1000 Genomes Project

References

- ↑ Cook-Deegan R (1989). "The Alta Summit, December 1984". Genomics. 5: 661–663.

- ↑ Barnhart, Benjamin J. (1989). "DOE Human Genome Program". Human Genome Quarterly. 1: 1. Retrieved 2005-02-03.

- ↑ DeLisi, Charles (2001). "Genomes: 15 Years Later A Perspective by Charles DeLisi, HGP Pioneer". Human Genome News. 11: 3–4. Retrieved 2005-02-03.

- ↑ "White House Press Release". Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS". Retrieved 2006-07-22. Text " Human genome finally complete " ignored (help); Text " Science/Nature " ignored (help)

- ↑ "Guardian Unlimited". Retrieved 2006-07-22. Text " Human Genome Project finalised " ignored (help); Text " UK Latest " ignored (help)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome" (PDF). Nature. 409: 860−921.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Venter, JC; et al. (2001). "The sequence of the human genome" (PDF). Science. 291: 1304−1351.

- ↑ IHGSC (2004). "Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome". Nature. 431: 931–945.

- ↑ Fiers W, Contreres R, Duerinck F, Haegeman G, Iserentant D, Merregaert J, Min Jou W, Molemans F, Raeymaekers A, Van den Berghe A, Volckaert G, Ysebaert M. Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene, Nature. 1976 Apr 8;260(5551):500-7.

- ↑ Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, Hutchison CA, Slocombe PM, Smith M., Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA, Nature. 1977 Feb 24;265(5596):687-95

- ↑ Fleischmann, R. D.; et al. (1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269: 496−512.

- ↑ C. elegans Sequencing Consortium (1998). "Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology". Science. 282: 2012–18.

- ↑ Adams, MD.; et al. (2000). "The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster". Science. 287: 2185−2195.

- ↑ Waterston RH, Lander ES, Sulston JE (2002). "On the sequencing of the human genome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99: 3712–6. PMID 11880605.

- ↑ Waterston RH, Lander ES, Sulston JE (2003). "More on the sequencing of the human genome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100: 3022–4. PMID 12631699.

- ↑ Osoegawa, Kazutoyo (2001). "A Bacterial Artificial Chromosome Library for Sequencing the Complete Human Genome". Genome Research. 11: 483–496.

- ↑ Kennedy D (2002). "Not wicked, perhaps, but tacky". Science. 297: 1237. PMID 12193755.

- ↑ Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL; et al. (2007). "The Diploid Genome Sequence of an Individual Human". PLoS Biology. 5 (10).

External links

- Delaware Valley Personalized Medicine Project Uses data from the Human Genome Project to help make medicine personal

- National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). NHGRI led the National Institutes of Health's (NIH's) contribution to the International Human Genome Project. This project, which had as its primary goal the sequencing of the three thousand million base pairs that make up human genome, was successfully completed in April 2003.

- Human Genome News. Published from 1989 to 2002 by the US Department of Energy, this newsletter was a major communications method for coordination of the Human Genome Project. Complete online archives are available.

- Project Gutenberg hosts e-texts for Human Genome Project, titled Human Genome Project, Chromosome Number # (# denotes 01-22, X and Y). This information is raw sequence, released in November 2002; access to entry pages with download links is available through http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/3501 for Chromosome 1 sequentially to http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/3524 for the Y Chromosome. Note that this sequence might not be considered definitive due to ongoing revisions and refinements. In addition to the chromosome files, there is a supplementary information file dated March 2004 which contains additional sequence information.

- The HGP information pages Department of Energy's portal to the international Human Genome Project, Microbial Genome Program, and Genomics:GTL systems biology for energy and environment

- yourgenome.org: The Sanger Institute public information pages has general and detailed primers on DNA, genes and genomes, the Human Genome Project and science spotlights.

- Ensembl project, an automated annotation system and browser for the human genome

- UCSC genome browser, This site contains the reference sequence and working draft assemblies for a large collection of genomes. It also provides a portal to the ENCODE project.

- Nature magazine's human genome gateway, including the HGP's paper on the draft genome sequence

- Wellcome charitable trust description of HGP "Your Genes, your health, your future".

- Learning about the Human Genome. Part 1: Challenge to Science Educators. ERIC Digest.

- Learning about the Human Genome. Part 2: Resources for Science Educators. ERIC Digest.

- Patenting Life by Merrill Goozner

- Prepared Statement of Craig Venter of Celera Venter discusses Celera's progress in deciphering the human genome sequence and its relationship to healthcare and to the federally funded Human Genome Project.

- Cracking the Code of Life Companion website to 2-hour NOVA program documenting the race to decode the genome, including the entire program hosted in 16 parts in either QuickTime or RealPlayer format.

- article by Leota Lone Dog, author of the 1999 article "whose genes are they" in the Journal of health and social policy, 10.4: 51-66. [4]

ar:مشروع الجينوم البشري da:HUGO de:Humangenomprojekt hr:Projekt humanog genoma id:Proyek Genom Manusia it:Progetto Genoma Umano he:פרויקט גנום האדם nl:Menselijk genoomproject no:Human Genome Project fi:Human Genome Project sv:Human Genome Project th:โครงการจีโนมมนุษย์