Dendritic cell

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

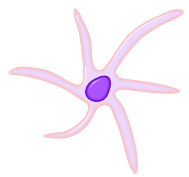

Dendritic cells (DCs) are immune cells and form part of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the surface to other cells of the immune system, thus functioning as antigen-presenting cells.

Dendritic cells are present in small quantities in tissues that are in contact with the external environment, mainly the skin (where they are often called Langerhans cells) and the inner lining of the nose, lungs, stomach and intestines. They can also be found in an immature state in the blood. Once activated, they migrate to the lymphoid tissues where they interact with T cells and B cells to initiate and shape the adaptive immune response. At certain development stages they grow branched projections, the dendrites, that give the cell its name. However, these do not have any special relation with neurons, which also possess similar appendages. Immature dendritic cells are also called veiled cells, in which case they possess large cytoplasmic 'veils' rather than dendrites.

History

Dendritic cells were first described by Paul Langerhans (Langerhans cells) in the late nineteenth century. It wasn't until 1973, however, that the term "dendritic cells" was coined by Ralph M. Steinman and Zanvil A. Cohn.[1]. In 2007 Steinman was awarded the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award for his discovery.

Types of dendritic cells

In all dendritic cells, the similar morphology results in a very large contact surface to their surroundings compared to overall cell volume.

In vivo - primate

The most common division of dendritic cells is "myeloid" vs. "plasmacytoid" (or "lymphoid"):

| Name | Description | Secretion | Toll-like receptors[2] |

| Myeloid dendritic cells (mDC) | are most similar to monocytes. mDC are made up of at least two subsets: (1) the more common mDC-1, which is a major stimulator of T cells (2) the extremely rare mDC-2, which may have a function in fighting wound infection |

IL-12 | TLR 2, TLR 4 |

| Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) | look like plasma cells, but have certain characteristics similar to myeloid dendritic cells.[3] | They can produce high amounts of interferon-alpha and thus became known as IPC (interferon-producing cells) before their dendritic cell nature was revealed.[4] | TLR 7, TLR 9 |

The markers BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4 can be used to discriminate among the types.[5]

Lymphoid and myeloid DCs evolve from lymphoid or myeloid precursors respectively and thus are of haematopoietic origin. By contrast, follicular dendritic cells (FDC) are probably not of hematopoietic origin, but simply look similar to true dendritic cells.

In vitro

In some respects, dendritic cells cultured in vitro do not show the same behaviour or capability as dendritic cells isolated ex vivo. Nonetheless, they are often used for research as they are still much more readily available than genuine DCs.

- Mo-DC or MDDC refers to cells matured from monocytes[6]

- HP-DC refers to cells derived from hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Nonprimate

While humans and non-human primates such as Rhesus macaques appear to have DCs divided into these groups, other species (such as the mouse) have different subdivisions of DCs.

Life cycle

Formation of immature cells

Dendritic cells are derived from hemopoietic bone marrow progenitor cells. These progenitor cells initially transform into immature dendritic cells. These cells are characterized by high endocytic activity and low T-cell activation potential. Immature dendritic cells constantly sample the surrounding environment for pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. This is done through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as the toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLRs recognize specific chemical signatures found on subsets of pathogens. Once they have come into contact with such a pathogen, they become activated into mature dendritic cells. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose pathogens and degrade its proteins into small pieces and upon maturation present those fragments at their cell surface using MHC molecules. Simultaneously, they upregulate cell-surface receptors that act as co-receptors in T-cell activation such as CD80, CD86, and CD40 greatly enhancing their ability to activate T-cells. They also upregulate CCR7, a chemotactic receptor that induces the dendritic cell to travel through the blood stream to the spleen or through the lymphatic system to a lymph node. Here they act as antigen-presenting cells: they activate helper T-cells and killer T-cells as well as B-cells by presenting them with antigens derived from the pathogen, alongside non-antigen specific costimulatory signals.

Every helper T-cell is specific to one particular antigen. Only professional antigen-presenting cells (macrophages, B lymphocytes, and dendritic cells) are able to activate a helper T-cell which has never encountered its antigen before. Dendritic cells are the most potent of all the antigen-presenting cells.

As mentioned above, mDC probably arise from monocytes, white blood cells which circulate in the body and, depending on the right signal, can turn into either dendritic cells or macrophages. The monocytes in turn are formed from stem cells in the bone marrow. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells can be generated in vitro from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Plating of PBMCs in a tissue culture flask permits adherence of monocytes. Treatment of these monocytes with interleukin 4 (IL-4) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) leads to differentiation to immature dendritic cells (iDCs) in about a week. Subsequent treatment with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa) further differentiates the iDCs into mature dendritic cells.

Life span of dendritic cells

Activated macrophages have a lifespan of only a few days. The lifespan of activated dendritic cells, while somewhat varying according to type and origin, is of a similar order of magnitude, but immature dendritic cells seem to be able to exist in an inactivated state for much longer.

Research challenges

The exact genesis and development of the different types and subsets of dendritic cells and their interrelationship is only marginally understood at the moment, as dendritic cells are so rare and difficult to isolate that only in recent years they have become subject of focused research. Distinct surface antigens that characterize dendritic cells have only become known from 2000 on; before that, researchers had to work with a 'cocktail' of several antigens which, used in combination, result in isolation of cells with characteristics unique to DCs.

Dendritic cells and cytokines

The dendritic cells are constantly in communication with other cells in the body. This communication can take the form of direct cell-to-cell contact based on the interaction of cell-surface proteins. An example of this includes the interaction of the receptor CD40 of the dendritic cell with CD40L present on the lymphocyte. However, the cell-cell interaction can also take place at a distance via cytokines.

For example, stimulating dendritic cells in vivo with microbial extracts causes the dendritic cells to rapidly begin producing IL-12.[7] IL-12 is a signal that helps send naive CD4 T cells towards a Th1 phenotype. The ultimate consequence is priming and activation of the immune system for attack against the antigens which the dendritic cell presents on its surface. However, there are differences in the cytokines produced depending on the type of dendritic cell. The lymphoid DC has the ability to produce huge amounts of IFN-a, more than any other blood cell.[8]

Relationship to HIV, allergy, and autoimmune diseases

HIV, which causes AIDS, can bind to dendritic cells via various receptors expressed on the cell. The best studied example is DC-SIGN (usually on MDC subset 1, but also on other subsets under certain conditions; since not all dendritic cell subsets express DC-SIGN, its exact role in sexual HIV-1 transmission is not clear). When the dendritic cell takes up HIV and then travels to the lymph node, the virus is able to move to helper T-cells, and this infection of helper T-cells is the major cause of disease. This knowledge has vastly altered our understanding of the infectious cycle of HIV since the mid-1990s, since in the infected dendritic cells, the virus possesses a reservoir which also would have to be targeted by a therapy. This infection of dendritic cells by HIV explains one mechanism by which the virus could persist after prolonged HAART. Many other viruses, such as the SARS virus seems to use DC-SIGN to 'hitchhike' to its target cells.[9] However, most work with virus binding to DC-SIGN expressing cells has been conducted using in vitro derived cells such as moDCs. The physiological role of DC-SIGN in vivo is more difficult to ascertain.

Altered function of dendritic cells is also known to play a major or even key role in allergy and autoimmune diseases like lupus erythematosus.

Dendritic cells in animals other than humans

The above applies to humans. In other organisms, the function of dendritic cells can differ slightly. For example, in brown rats (but not mice), a subset of dendritic cells exists that displays pronounced killer cell-like activity, apparently through its entire lifespan. However, the principal function of dendritic cells as known to date is always to act as the central command and central encyclopedia of the immune response, or similar to servers in a computer network. They collect and store the immune system's "knowledge", enabling them to instruct and direct the adaptive arms in response to challenges.

Novel subpopulations of dendritic cells have been recently identified in the mouse.

- Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells (IKDC)[10] have been shown to display a role in tumor protection. Although it produces interferon-alpha, as for plasmacytoid dendritic cells, it can be distinguished from the latter by its cytotoxic potential and the expression of markers usually found on NK cells.

- In addition, an immediate precursor to myeloid and lymphoid dendritic cells of the spleen has been identified.[11] This precursor, termed pre-DC, lacks MHC surface expression.

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

See also

- List of human clusters of differentiation for a list of CD molecules (as CD80 and CD86)

External links

- Dendritic+Cells at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Dendritic cells Presented by the University of Virginia

- www.dc2007.eu : 5th International Meeting on Dendritic Cell Vaccination and other Strategies to tip the Balance of the Immune System

- Website of Dr. Ralph M. Steinman at The Rockefeller University contains information on DCs, links to articles, pictures and videos

References

- ↑ Steinman RM, Cohn ZA (1973). "Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution". J. Exp. Med. 137 (5): 1142–62. PMID 4573839.

- ↑ Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A (2002). "The instructive role of dendritic cells on T-cell responses". Arthritis Res. 4 Suppl 3: S127–32. PMID 12110131.

- ↑ McKenna K, Beignon A, Bhardwaj N (2005). "Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity". J. Virol. 79 (1): 17–27. PMID 15596797.

- ↑ Liu YJ (2005). "IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors". Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23: 275–306. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. PMID 15771572.

- ↑ Dzionek A, Fuchs A, Schmidt P, Cremer S, Zysk M, Miltenyi S, Buck D, Schmitz J (2000). "BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood" (PDF). J Immunol. 165 (11): 6037–46. PMID 11086035.

- ↑ Ohgimoto K, Ohgimoto S, Ihara T, Mizuta H, Ishido S, Ayata M, Ogura H, Hotta H (2007). "Difference in production of infectious wild-type measles and vaccine viruses in monocyte-derived dendritic cells". Virus Res. 123 (1): 1–8. PMID 16959355.

- ↑ Reis e Sousa C, Hieny S, Scharton-Kersten T, Jankovic D; et al. (1997). "In vivo microbial stimulation induces rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas". J. Exp. Med. 186 (11): 1819–29. PMID 9382881.

- ↑ Siegal FP, Kadowaki N, Shodell M, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly PA; et al. (1999 June 11). "The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood". Science. 284 (5421): 1835–7. doi:10.1126/science.284.5421.1835. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Yang, Zhi-Yong; et al. (2004). "pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN". J. Virol. 78 (11): 5642–50. PMID 15140961.

- ↑ Welner R, Pelayo R, Garrett K, Chen X, Perry S, Sun X, Kee B, Kincade P. "Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells (IKDC) arise via a unique differentiation pathway from primitive c-kitHiCD62L+ lymphoid progenitors". Blood. PMID 17317852.

- ↑ Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A; et al. (2006 Jun). "Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes". Nature Immunolgy. 7 (6): 663–71. doi:10.1038/ni1340. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

de:Dendritische Zelle ko:수지상 세포 id:Sel dendritik he:תא דנדריטי nl:Dendritische cel ur:شجری خلیہ